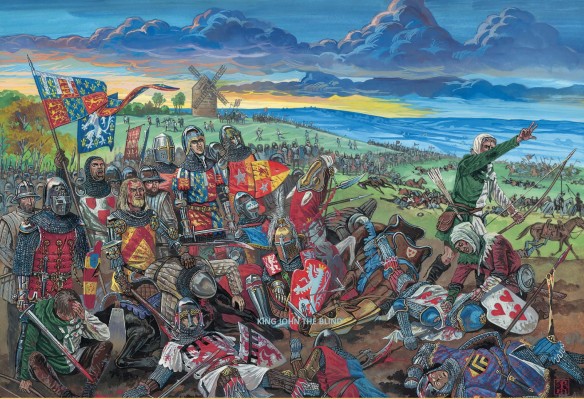

The death of bind King John of Bohemia, who led the attack on the right flank of the British at Crecy 1346. John the Blind (Jan; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346) was the count of Luxembourg from 1313 and king of Bohemia from 1310 and titular king of Poland. He is well known for having died while fighting in the Battle of Crécy at age 50, after having been blind for a decade.

According to historian Clive Bartlett, the English armies of the 14th century, including the longbowmen, mainly comprised the levy and the so-called ‘indentured retinue’. The latter category entailed a sort-of contract between the King and his nobles that allowed the monarch to call upon the retainers of the noblemen for purposes of wars (especially in the overseas).

This pseudo-feudal arrangement fueled a class of semi-professional soldiers who were mostly inhabitants from around the estates of the lords and the kings. And among these retainers, the most skilled were the longbowmen of the household. The archers from the King’s own household were termed the ‘Yeomen of the Crown’, and they were rightly considered the elite even among the experienced archers.

The other retainers came from the neighborhoods of the great estates, usually consisting of followers (if not residents) of the lord’s household. Interestingly enough, many of them served the same purpose and received similar benefits like household retainers. There was also a third category of the retainer longbowman, and this group pertained to men who were hired for specific military duties, including garrisoning and defending ‘overseas’ French towns. Unfortunately, in spite of their professional status, these hired retainers often turned to banditry, since official payments were not always delivered in time.

The Battle

A key battle in the opening phase of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453). England’s Edward III (1312-1377) led an army on an extended chevauchée into northern France with the intention of provoking Philip VI to give battle. The tactic nearly backfired when the French burned several bridges in an effort to trap the English against the Somme: Edward was fortunate to ford under cover of his skilled archers. Two days later the armies met near the village of Crécy, in Normandy, where they formed opposing battle lines 2,000 yards long. The English were well-rested and fed. Though outnumbered 2:1 they took position atop a low ridge with their left flank abutting a stream, the Maie, and their right flank touching Crécy Wood. At the center were three blocks of men-at-arms with protecting pikemen. Two sets of archers with longbows were on the flanks, each in a “V” formation. Each archer had ready about 100 broad arrows, their lethal metal tips pushed into the ground to permit rapid reloading. Hundreds of caltrops were scattered atop the sod and mud to their front, to hobble oncoming warhorses or infantry. Tens of thousands more arrows were packed in wood and leather quivers stacked in carts to the rear. This large supply was key to the English victory. The initial rate of fire of a good longbowman was from six to ten arrows per minute, falling thereafter as muscle fatigue set in. Several hundred thousand arrows thus were likely fired toward the French that day, most from beyond the range of effective retaliation by the gay, pennant-decked lances of the French knights, looking splendid in burnished armor, colorful livery, and plumed helms, but utterly exposed to plunging arrow storms. Nor could Edward’s archers be reached by Genoese mercenaries on the French side firing stubby quarrels from crossbows, a deadly and feared weapon of their chosen profession that was wholly outmatched in range by the longbow on this bloody day.

Neither French cavalry nor Genoese infantry nor the Czech mercenaries of “Blind King John,” an allied prince, had ever faced the longbow. In ignorance and battle lust, they arrived piecemeal on the field of battle in the late afternoon, hungry and tired but straining to attack the English line. Heavy rain had soaked the field, turning it into sticky mud. The sun also favored the English, as it shone into the faces of the French. When the French heavy cavalry arrayed for the attack it formed in the old manner: a mass of armored horse supported by crossbow fire on the flanks and to the front. It is thought that Edward fired several small cannon at the Genoese to break up their formations. If true, these guns would have been so primitive they likely produced more a psychological than a physical effect. What mattered was that the Genoese were slowed by the Normandy mud and then slaughtered by flights of English arrows, not cannon, well before they got into crossbow range. Worse, in the rush to battle most had left their pervase with the baggage wagons. Nor could their slow-loading crossbows do comparable damage to the rapid-firing Welsh and English archers, thus rendering the Genoese attack ineffective and leaving the English lines unbroken and unharried before the French horse arrived. As casualties mounted among the Genoese they broke, turned, and ran, mud sucking at their boots and adding to the agony of panic as they exposed their backs to deadly enemy archers, firing aimed shots at the level.

The French knights, filled with Gallic disdain for everything on foot, spurred callously through the retreating Genoese, slashing at hired infantry in utter contempt, some with cries of “kill this rabble!” A large earthen bank channeled the French cavalry into a narrow front. Edward’s archers, positioned nearly perfectly, now turned their bows against the plodding, funneled cavalry and cut it down, too. Ill-formed, repeated French charges, with horsemen at the rear pushing hard against the forward ranks, were repulsed time and again by the longbowmen. Most were broken apart before they began, with staggering losses among the brave but reckless fathers and sons of the nobility of France. Edward’s archers kept up an extraordinary rate of fire, impaling knights and horse alike and hundreds of men-at-arms. No cowards the French, despite the carnage they charged, again and again. It is thought they made as many as 16 charges that day, utterly bewildered at their inability to beat or even reach an inferior enemy. For two centuries heavy cavalry had dominated battlefields from Europe to the Holy Land. But at Crécy there were no tattered squares of scrambling peasants to skewer on great lances, no clumps of overmatched men-at-arms to chase down with mace or run through on one’s sword. Instead, the chivalry of France met flocks of missiles that felled knight and mount alike at unheard of killing distances. Eye-witnesses reported French awe at the flapping, vital sounds of thousands of feathers on long-shafted arrows arcing in high swarms from an unreachable ridge, to plunge into men, horses, or both. Baleful accounts survive telling how arrows ripped through shields and helmets, pierced faceplates and cuirasses, and arms, legs, and groins, or pinned some best friend to his mount.

Much of this occurred at incredible distances, as unaimed plunging fire reached the French from as far away as 250-300 yards. Longbow accuracy only improved at closer ranges, as bows were leveled and each shot singly aimed at the lumbering steel and flesh targets the French cavalry presented. In prior battles cavalry had been safe at 200 yards or more, the usual distance where riders massed before trotting forward to about 60-100 yards, the distance at which they began the charge. Now death and piercing wounds fell from the sky at double the normal range, slicing through shields and armor to stab deep into chest or thigh, or horse. The French could make no reply to this long-distance death with their lances and swords: knights died in droves that day without ever making contact with their enemies. Armor was pierced and limbs, backs, and necks broken as falling knights entangled in bloody clots of swords and snapped lances, and kicking and screaming dying men and horses. So they charged: anything was better than standing beneath such lethal rain. The nearly 8,000 longbowmen at Crécy probably fired 75,000-90,000 arrows in the 40-60 seconds it took the French to close the range, each arrow speeding near 140 miles per hour, each archer keeping two and some three in the air at once. Those knights who reached the English lines piled up before them, pierced with multiple arrows and forming an armor-and-flesh barrier in front of the English men-at-arms that impeded fresh assaults. With French chivalry broken and its survivors staggering in the mud, the English infantry and Edward’s dismounted knights closed in to kill off the lower orders and take nobles prisoner, to be held for later ransom. Then the English stood in place through the night, holding in case of a renewed attack in the morning which never came.

Most casualties at Crécy were inflicted by the longbow and thus losses were hugely lopsided: between 5,000 and 8,000 French and Genoese were killed, including as many as 1,500 knights, compared to about 100 of Edward’s men. This was a huge number for a 14th-century battle, and left nearly every castle and chateau in France in mourning. The defeat of its warrior elite shattered France’s military capabilities and shook its confidence for a generation. This one-sided battle further eroded the old illusion that heavy cavalry was invincible against common infantry, and elevated recognition of the importance of archers across Europe. A parallel effect was that for the next 50 years French knights, too, preferred to dismount to fight, a practice they followed until better horse armor was made that enticed them back into the saddle at Agincourt.

Suggested Reading: Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston, The Battle of Crécy, 1346 (2005); Alfred H. Burne, The Crécy War (1955; 1999); G. C. Macauly, ed., The Chronicles of Jean Froissart (1904); Henri de Wailly, Crécy, 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (1987).