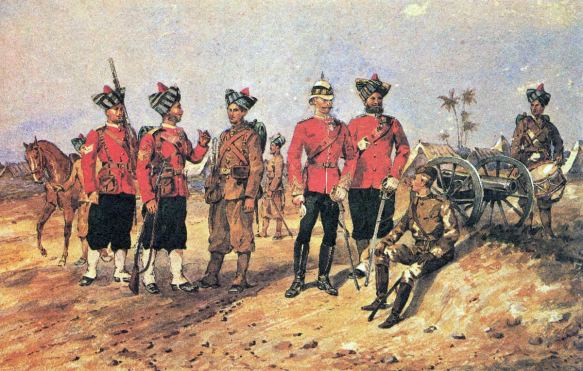

19th Bombay Native Infantry: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

As the British prepared to withdraw their army from Afghanistan, a column was ambushed and wiped out at Maiwand. The survivors fled back to Kandahar where they and the British garrison were besieged by an Afghan army under Ayub Khan. The British high command feared that the defeat and impending disaster at Kandahar could turn the planned British withdrawal into a rout. Therefore Lieutenant – General Sir Frederick Roberts was ordered to take a column of British and Indian troops from Kabul and relieve the garrison in Kandahar. On 8 August 1880 Roberts began an epic march in which he covered 480km (300 miles) in three weeks. Just before the arrival of Roberts at Kandahar, the Afghans raised their siege and retired to a strong defensive position along a ridgeline to the west. On 1 September Roberts began his attack with a diversion against the Baba Wali Pass, which controlled the road west. With the Afghans engaged, he then sent his assault force in a flanking movement. The infantry brigades stormed a pair of fortified villages, Gundimullah Sahibdad and Gundigan, followed by the village of Pir Paimal. The British then overran the camp of Ayub Khan and routed his army.

9th Lancers on the march to Kandahar, water-colour by Orlando Norie. The troops would march in the early morning to avoid the full heat of the sun, halting a few minutes every hour. In this way, the column managed to cover up to 20 miles a day.

March to Kandahar

Lieutenant-General Donald Stewart (1824-1900) was organizing the withdrawal from Kabul when news of the disaster arrived. He formed a relief column and placed Roberts in charge, with orders to march from Kabul to Kandahar and save Major-General Primrose’s command. It was a dangerous situation. Roberts would have to march 480km (300 miles) with no supplies other than those which his column carried and what it could scrounge from the countryside, for Kabul was to be abandoned and the remainder of the British forces withdrawn, even while Roberts made his arduous march. Nevertheless, morale was high. The soldiers had been informed that they were setting out to save their fellow British and imperial soldiers, and also that they were not to garrison Kandahar but would be returning to India once the mission was complete.

Roberts had a handful of cavalry and a few artillery batteries, but the strength of his column lay in his elite infantry regiments. The 92nd Gordon Highlanders and 72nd Seaforth Highlanders were both battle-hardened outfits, two of the finest regiments in the British Army. Armed with Martini-Henry rifles, they were a superbly equipped and trained force. Along with them came the native contingents composed of Indians, Sikhs and Gurkhas.

Although, as per British policy, native regiments did not carry the latest weaponry, their Lee-Snider rifles were still good weapons, and the men that carried them were loyal, well trained and ferocious fighters. Roberts would later write of the ‘fierce warrior races’ that were natural soldiers in his native infantry regiments, a reference to the Sikhs and Gurkhas. All told, they made a colourful lot, reflecting the strength of the British Army, and some observers pronounced Roberts’ column to be nothing less than the finest Anglo-Indian force ever put together for a campaign. The column set off on the march to Kandahar on 8 August 1880. Thanks to favourable alliances with Afghan tribal leaders who were as anxious to see the British go as they were to deal a blow against Ayub Khan, their rival for power in Afghanistan, there was no significant Afghan resistance to the march. That said, the column was occasionally subjected to random attacks by guerrilla forces that hovered around the flanks and tail of the column. The main problem was thus not enemy forces, but the gruelling conditions endured by the men along the march. The advance was made in blistering heat. Although food and fodder could usually be found or purchased from the locals, fresh water was in short supply for much of the march. Temperatures hovered around 35°C (95°F) throughout the long advance, and the dense cloud of dust raised by the marching column as it pounded south through the bleak countryside choked men and animals. The chronic water shortage turned each day’s march into a test of endurance. Roberts tried to alleviate this somewhat by beginning the daily slog in the pre- dawn darkness and halting around noon, but the hard fact was that there was no escaping the blistering heat and thirst which dogged each man.

Roberts moved his column at a fierce pace, at times covering as much as 34km (21 miles) in a single day. Supporters claimed his haste was based upon his desire to save the garrison at Kandahar. Less generous critics countered that he was trying to outdistance a second relief column under Major-General Robert Phayre, who had also been dispatched to relieve Kandahar. In fact, some observers dubbed the dual relief marches the Race for the Peerage’. In reality, Roberts was probably motivated by both duty and a quest for glory, motivations that were hardly a vice in a soldier of empire.

Heatstroke and disease weakened the force along its arduous path, and at times there was some confusion in the column, leading to delays, but there was little straggling in spite of the conditions. Part of this was because Roberts had a force of soldiers deployed at the rear of the column to keep any stragglers from wandering. Camp followers and indigenous workers helping with the supply wagons were the worst offenders, but very few soldiers fell out of the march. These men were veterans and, besides their discipline, they all knew what fate awaited a straggler in the hills of Afghanistan. The fear of a death that would be as certain as it was hideous kept many a man moving forwards on the march to Kandahar.

The Battle of Kandahar: 1 September 1880

At last Roberts’ column reached the village of Khelat-i-Ghilzai, about 80km (50 miles) from Kandahar. There it rendezvoused with a small British garrison, obtained ample supplies of water and food, and enjoyed the first real halt since the march had begun. While his army rested, Roberts received news that Ayub Khan had learned of the relief column and had consequently lifted the siege of Kandahar and withdrawn his army to a defensive position in the hills west of the city. Roberts was pleased that Ayub Khan was apparently offering battle. He absorbed the garrison at Khelat-i-Chilzai into his column and then moved his reinforced army at a much more leisurely pace. He entered Kandahar unopposed on 31 August, having covered 480km (300 miles) in just three weeks.

Roberts was senior in rank to Primrose and so assumed command of the British forces in Kandahar. On 31 August, he sent out a reconnaissance in force west of the city, and the probe revealed that the strength of the Afghan forces was concentrated to deny passage through the Baba Wali Pass in the centre. Roberts therefore dismissed the idea of a drive up the centre. He opted instead for a turning movement against the Afghans’ right flank. He would then sweep around the ridgeline and drive north up the western slopes to storm Ayub Khan’s camp. Ayub apparently noticed the potential weakness of his position, for during the night of 31 August he strongly reinforced the villages of Gundimullah Sahibdad and Gundigan, which anchored his right flank.

The Assault Begins

At 9-30 a. m. on 1 September 1880, British heavy artillery began pounding the Afghan positions dominating the Baba Wali. As the British guns duelled the Afghan artillery, Roberts sent a force of Indians in a feint attack towards the Baba Wali Pass. With the attention of the Afghans fixed on this point, he sent his powerful infantry contingent of three brigades in an attack on the Afghan right flank. The 1st Brigade, composed of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders and the 2nd Gurkhas, attacked the village of Gundimullah Sahibdad. The Afghans were strongly established in the stone houses of the village and put up a stiff fight. Rifle fire was ineffective against an enemy in stone houses loop-holed and prepared for defence. There was thus only one way to clear the village, and that was at the point of a bayonet. The big Scotsmen and small Gurkhas made for an odd pairing, but together they were the finest infantry in the world. Pressing home their attack through a hail of Afghan rifle fire, they closed with the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. Afghan resistance was broken by 10.30 and the village fell to the British. Without a moment’s hesitation, the 1st Brigade recommenced its advance, rushing on to continue the turning movement.

Meanwhile to the south, the 2nd Brigade, consisting of the 2nd Sikhs and the 72nd Seaforth Highlanders, met stiffer resistance at Gundigan. They had first to advance through a maze of walled orchards and irrigation ditches, which were easily defended and broke up the momentum of the attack. The 72nd’s commanding officer was felled by an Afghan bullet, but the regiment pushed on. Once more, the issue was decided not by rifle fire but by bayonets in close-quarter fighting. The Afghans could not hold Gundigan either, and by 11.15 it too had fallen to the British.

The two attacking infantry brigades rounded the right flank of the Afghans’ defensive line, pausing only briefly to organize before rushing into the attack against the village of Pir Paimal, the last bastion between them and their objective. Without artillery support, the infantry had to go it alone and once more the decision was made to rush the Afghans and seize the fortified village at bayonet point. In a few desperate moments, the fight was over and the British infantry brigades found themselves in possession of the village. Roberts’ flanking attack had been successful and, indeed, had unhinged the entire Afghan position. He now ordered his 3rd Brigade, previously kept in reserve, forward to Pir Paimal to provide a fresh force for the final drive into the heart of the Afghan position and the seizure of Ayub Khan’s camp.

Kandahar: 92nd Highlanders storming Gundi Mulla Sahibdad. Oil by Richard Caton Woodville

Highlander Assault

The British forces were by now exhausted, but they faced a final defensive line that was the strongest of all. An elongated ditch was held in strength and backed up by a fort and a small knoll, swarming with Afghan regulars and supported by powerful artillery. This included the heavy guns deployed along the Baba Wali, which were now swung round and trained on the British infantry brigades. The best Afghan infantry units defended this final position, and unlike the mass of irregulars routed from the previous villages, they were armed with better weaponry, including captured Lee-Snider and Martini-Henry rifles. Major George White (1835-1912), who would eventually become a field marshal of the British Army, now seized the moment and led the 92nd Highlanders forward in a wild charge. They were closely followed by the 2nd Gurkhas and the 23rd Bengal Native Infantry They moved swiftly through a hail of rifle fire and bursting shells, overrunning the Afghan defensive positions in such a bold attack that the enemy was completely unnerved. As the infantry drove into Ayub Khan’s camp, the Afghan position collapsed and the battle was lost.

Ayub Khan’s army began streaming off the battlefield, and should have been decimated by pursuing British cavalry, but the British horse were poorly handled in this battle and failed to pursue properly. The brunt of the battle had been borne by the hard-marching and hard-fighting infantry, which had been at the heart of the action from the opening march out of Kabul to the final denouement at Kandahar. Roberts was showered with accolades and medals, and emerged from the campaign as one of the greatest generals of the British Army. His arduous march and triumphant victory silenced his critics and, already beloved of his troops, made him one of the great heroes of the Victorian age.

The battle of Kandahar ended the Second Afghan War on a high note for the British and allowed them to withdraw their forces from Afghanistan with honour. They had proven once more that discipline and training could overcome numbers, and that their armies were capable of undertaking large-scale incursions into the most desolate and isolated reaches of the earth. Unlike in the Zulu War, British infantry had relied far more upon shock action than rifle fire to decide battles. This had worked against an ill-trained opponent of roughly equal strength. At Kandahar, the training, discipline and courage of the British infantry to close with the enemy in hand-to-hand combat were the factors that decided the day. Still unresolved, however, was the harder problem of how to subdue a region and assert a colonial power’s authority over a tribal society whose hatred for foreigners was exceeded only by their hatred of their rival tribesmen. Britain kept the Northwest Frontier out of unfriendly hands, but a long-term solution to the quandary of Afghanistan remained beyond the reach of even the greatest imperial power of the nineteenth century.