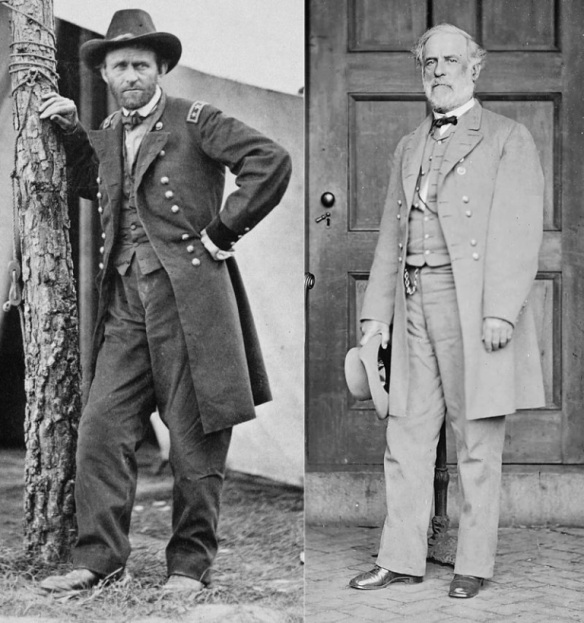

Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, respectively, opposing commanders in the Overland Campaign.

The Army of the Potomac didn’t know quite what to make of Ulysses Grant. Modest to a fault, he was the inverse of peacocks like McClellan and Hooker, whose preening bombast belied their mediocrity, while his quiet decisiveness would prove the antidote to the hesitation that had characterized Meade’s lackluster leadership ever since Gettysburg. It wasn’t always thus. Until 1861, Grant was a study in failed promise: graduation from West Point followed by distinguished service in the Mexican War that petered out into dreary years of garrison duty, rumors of alcoholism, and a succession of unrewarding and unrewarded civilian trades in the backwaters of Missouri and Illinois. A Douglas Democrat in politics, he had harbored mixed feelings about slavery. The Civil War rescued him from obscurity, but unlike most it also rocketed him within months from victory to victory, beginning with the seizure of enemy posts on the Mississippi, the brilliant capture of Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and the Cumberland, the stunning recovery from near-defeat at Shiloh, the triumph at Vicksburg, and the relief of Chattanooga.

Promising to bring a new aggressive spirit to the so often defeated eastern army, he called up spare troops from as far away as New York and Boston, and stripped the defenses of Washington to restore the Army of the Potomac to more than 120,000 men, its greatest size since 1862. “We had to have hard fighting,” Grant later wrote. “The two armies had been confronting each other so long, without any decisive result, that they hardly knew which could whip.” He retained Meade as the army’s nominal commander, although in practice the victor of Gettysburg served as something closer to a senior chief of staff for Grant, who planned the army’s movements. In contrast to his predecessors, Grant saw the Army of the Potomac’s overland campaign as but one piece, if the largest one, of a multi-pronged campaign to assault the Confederates simultaneously on every front. William T. Sherman, Grant’s successor as commander of the Army of the Tennessee, would strike for Atlanta, the Confederacy’s western manufacturing center and railroad hub. Gen. Nathaniel Banks would drive up the Red River into the heartland of Louisiana. A combined land and sea force would assault Mobile, the Confederacy’s last major port on the Gulf of Mexico. Yet another army under Gen. David Hunter would campaign down the Shenandoah Valley. And while Grant himself marched south into Virginia in pursuit of Robert E. Lee, Gen. Benjamin Butler with another 36,000 men would swing inland from Chesapeake Bay to envelop Richmond from the south. Altogether, it was the most comprehensive and coordinated war plan that the Union had yet attempted, and its complexity a testament to the strategic sophistication of Grant’s mind.

The Army of the Potomac in 1864 was no longer the battle-hungry and undisciplined mob that had stumbled into defeat at Bull Run three years earlier. It had been bloodied many times over since then. Most of the early volunteers were now dead or maimed, or had declined to reenlist after their three years were up. Although a steely patriotism, comradeship, and a determination to finish the job they had started all played their part, many of the veterans who still remained searched their souls for the strength to continue. One of them, Elwood Griest, a Pennsylvanian from Lancaster County, tried to explain to his wife how he coped with the pervasiveness of suffering and death. “I am more than ever convinced that life, strange and mysterious as it may seem to us, is but the sure and unerring workings of a grand machine, as much above our comprehension as the most complicated machinery of human invention is above the comprehension of brute creation. This being the case, we may go forward on life’s journey without fear, confident that whatever may happen, we are but contributing to the grand result.”

Along with veterans like Griest, tens of thousands of often unwilling draftees now filled the ranks. Even more were men who had been paid by affluent draftees to serve as hired substitutes. At the beginning of the war, bounties of $40 or $50 were common; by 1864, it often cost more than $1,000 to entice men to enlist. Thaddeus Stevens personally offered a bounty of $150 to every man in the first two companies from Lancaster County to volunteer for twelve months’ service under the most recent Enrollment Act, plus a bonus of $50 for the first three companies whose officers pledged to abstain from liquor while in service. Apart from the standard $300 federal fee, many others were paid bounties by cities and towns, businesses and private donors such as Stevens, so that states could fill their draft quotas without resorting to politically risky mass conscription. Not surprisingly, many such men soon deserted and often reenlisted elsewhere to claim another bounty, and then absconded again: in one Connecticut regiment, 60 out of 210 recruits decamped within their first three days in camp. A satirical cartoon in Harper’s Weekly that winter showed a broker leading a weedy-looking drunk into a barber shop, saying, “Look a-here—I want you to trim up this old chap with a flaxen wig and a light mustache, so as to make him look like twenty; and as I shall probably clear three hundred dollars on him, I sha’n’t mind giving you a fifty for the job.”

Once again, the Army of the Potomac crossed the desolation of northern Virginia, littered with abandoned fortifications, earthworks, old camps, rifle pits, burned bridges, wrecked railroad cars, ruined woodlands, and untilled fields. Even houses were scarce, having been torn apart for firewood by one army or another. On May 5, Grant collided with a Confederate army about half the size of his own near the old Chancellorsville battlefield, in the wasteland of scrub pine, briars, oak, swamps, and thickets known locally as the “Wilderness.” Human skulls and bones left from the former battle were strewn everywhere, a forbidding sight for men about to go into battle. Maneuver was close to impossible. The narrow roads jumbled ranks and the dense woods wiped out the Union’s advantage in artillery. For two days the armies grappled in bloody melees and fell in tangled heaps to devastating rifle fire from enemies hidden in the trees. Brushfires roasted hundreds of wounded alive, terrifying the living with their screams and the stink of burning flesh. The stalemate left more than seventeen thousand federals and eleven thousand Confederates killed, wounded, and captured. Several of Grant’s senior officers advised him to retreat as every thwarted commander before him had done. He ignored them. He directed the army to skirt Lee’s flank and keep marching south. Despite their wounds and their weariness, when the soldiers realized that Grant would not take them back to Washington, wild cheers echoed through the forest. Men swung their hats, flung up their arms, and cried, “On to Richmond!” with a gusto that they had not felt for many months.

On May 9, the two armies met again near Spotsylvania Court House, eight miles to the south. Grant hammered hard at the Confederate line but failed to break it. May 12 saw the longest sustained combat of the war, as for twenty-one hours straight soldiers battled only a few feet apart, standing atop the mingled dead and wounded three and four deep to poke their rifles over the breastworks, as the wounded writhed in agony beneath them. Wrote one federal soldier, “I saw one [man] completely trodden in the mud so as to look like part of it and yet he was breathing and gasping.” Federal losses at Spotsylvania surpassed 18,000, the Confederates’ somewhat less. Over just two weeks, the Army of the Potomac had been reduced by 36,000 men, more than a third of its number; the Confederates were diminished by about 24,000, a slightly greater proportion of their total. Stymied but undefeated, Grant once again sidestepped the enemy’s position and pushed on south.

Northern newspapers barely mentioned the slaughter, instead emphasizing the skill of the generals and the bravery of the men. The Lancaster Examiner jauntily characterized Grant’s slog as “a footrace to Richmond,” and with a trumpeting boldface headline screamed—quite inaccurately—“Butler on the War Path! He is successful everywhere!” even as that hapless general succumbed to tactical paralysis. The soldiers, of course, knew the truth. The sheer bloodiness of the campaign traumatized even the most battle-hardened. Elwood Griest wrote to his wife, “What a ghastly spectacle do the dead present, torn and mutilated in every conceivable way their unburied corpses cover the country for miles and miles in every direction. I pray that I may be spared from seeing any more.” And in a scribbled note to his parents, future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, “It is still kill—kill—all the time,” adding a few days later, “I tell you many a man has gone crazy since this campaign has begun from the terrible pressure on mind & body.”

Only slowly did the magnitude of what was happening make itself felt in Washington. The atmosphere there became increasingly grim. “It is a tearful place here now,” wrote Rep. James A. Garfield to his wife from Washington. “While the thousands of fresh troops go out to feed the great battle mills the crushed grain comes in.” The wounded swamped field hospitals and piled up on train platforms and wharves. It got only worse. On June 3, in what Grant himself recognized as his worst mistake of the campaign, he ordered another frontal assault on Lee’s lines at Cold Harbor, ten miles east of Richmond. Veterans knew it was suicidal and wrote their names on scraps of paper so that their bodies could be identified later. Grant lost six thousand men that morning, more than half of them in the first half-hour, but failed again to dent Lee’s lines. When another assault was ordered that afternoon not a man stirred, refusing to commit suicide in what looked like a foregone massacre.

Grant realized that Cold Harbor was a watershed. Depleted, numb with exhaustion, shaken by trauma, and unwilling to attack dug-in Confederates, the Army of the Potomac was essentially fought-out. Since the beginning of the campaign, it had lost some 55,000 men, of whom more than 7,000 had been killed. A single division in the Second Corps had suffered the appalling loss of 72 percent of its strength since the campaign began. The Confederates had lost between 30,000 and 35,000, many of them irreplaceable.

Apart from Adm. David Farragut’s dramatic seizure of Mobile—“Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead,” he famously cried as he ordered his warships into the heavily mined bay—all the other pieces of Grant’s ambitious strategy had come to naught. Hunter had been driven ignominiously from the Shenandoah Valley. Butler had allowed himself to be bottled up by a much smaller enemy force outside Petersburg. Sherman was still maneuvering toward Atlanta. Banks had been thrown back in Louisiana. Grant had brought Lee to bay in the ring of fortified trenches around Richmond and Petersburg, but the Confederates still held their capital, and they were still willing to fight. Yet another year that had begun with high hopes and another celebrated general seemed to be sinking into torpid stalemate.

In Washington, as renewed public disillusionment with the war set in, tempers were on a hair-trigger. Zachariah Chandler, Ben Wade’s rough-mannered Senate colleague from Michigan, was dining with friends at the National Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue when he was overheard denouncing Copperheads by Rep. Daniel Voorhees of Indiana, who was sitting nearby. Voorhees rose, stepped closer to Chandler, and slapped him in the face. The two, both big men—Voorhees was known as “The Tall Sycamore of the Wabash”—then began wrestling across the dining room. When Chandler appeared to be getting the better of Voorhees, the Indianan’s companion, a man named Hannigan, rushed to his aid. Seizing a pitcher of milk from a nearby table, he smashed it over Chandler’s head, spraying milk over everyone nearby and leaving Chandler stunned. Hannigan then hit him again with a chair, at which point the men were finally separated, with great difficulty, by bystanders. It was a foretaste of the political campaign that was just getting under way.

In Congress, Elihu Washburne of Illinois rose to deliver a paean of thanks to the soldiers of the Union. Precisely a year to the day, July 3 1864, had passed, he said, since the armies of the North and South had grappled at Gettysburg. Yes, many men and much matériel had been lost since then. But federal arms were triumphant from Arkansas to Virginia. Sherman was just eighteen miles from Atlanta, “the great rebel heart of the Southwest.” And Lee? Two months ago he had confronted the federal army on the Rapidan with “one hundred and thirty thousand of the best soldiers of the bogus confederacy.” (This was a considerable exaggeration, but no one corrected him.) Two months later, Washburne went on, General Grant—“that child of victory”—had now “driven the desperate and maddened hordes of Lee through sixty miles of his intrenchments, outgeneraling him in every movement, and beating him in every battle. He now holds both Petersburg and Richmond by the throat.” (This was another exaggeration.) The entire military situation never looked more promising, he claimed. “Returning to our seats on the 1st of December, as I hope we all may, I trust we shall see the rebellion crushed, peace restored, and the country regenerated and disenthralled.”