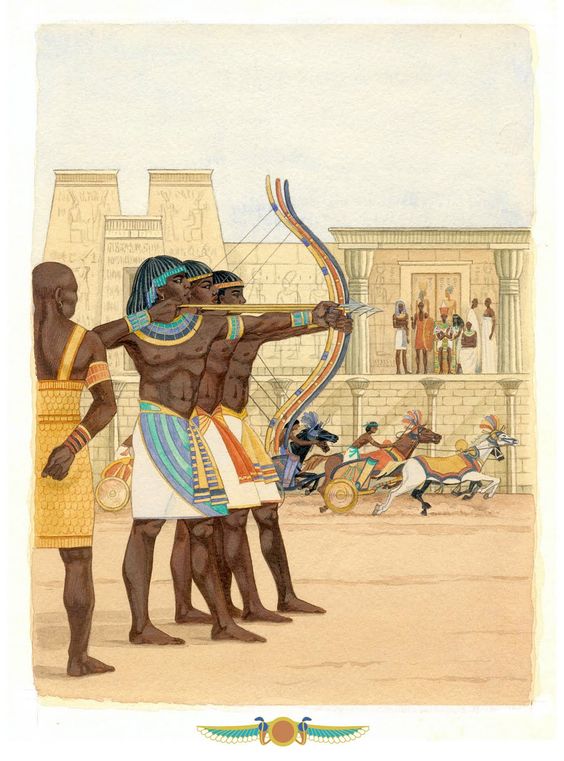

Egyptian warriors (New Kingdom) by Jose Antonio Penas

By the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty body armor was beginning to be used by some. Even foot soldiers had protective wrappings of linen or leather over vulnerable spots, and a kind of helmet to protect the head. More elaborate armor consisted of a linen or leather shirt covered with overlapping metal scales. It must have been horribly heavy and cumbersome (though not as bad as medieval armor). The king’s Blue Battle Crown, of leather sewed with metal discs, probably began its career as a head protector in battle, although it soon became one of the ceremonial crowns. Charioteers carried big shields to protect themselves and the warrior they drove, and even the horses wore heavy blankets that covered most of their backs. The little mare that may have been owned by Senenmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s henchman, had such a blanket of quilted leather lined with linen to prevent chafing.

The army that carried this arsenal into battle was a different thing altogether from the conscript armies of the Old Kingdom. We can give some of the credit for this—if credit it is—to the Hyksos again, since it was the effort of driving these foreigners out of Egypt that began the habit of campaigning which ended in imperial conquest. Beginning with Ahmose, who pushed the Hyksos out of Egypt into Palestine, and culminating in Thutmose III, who brought Syria-Palestine under Egyptian control and defeated the powerful kingdom of Mitanni, the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty were seasoned campaigners. Under Thutmose III the army went out to fight in Asia every year for almost twenty years; it must have been an annual occurrence as predictable as the inundation. The men who survived these campaigns were no longer amateur soldiers.

The army of the Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties was divided into groups of about five thousand men, each division being named after the god whose standard it bore. These standards are fascinating objects—images of gold or gilded wood, carried on high poles so that they could be seen above the dust of battle and, presumably, spur their defenders on to greater valor. Each division consisted of twenty-five companies of two hundred men each, and these companies also had their standards. Some were simple painted squares of wood, others bore designs like the one that showed two men wrestling. The royal marines carried standards shaped like ships. The literature of war contains no noble, high-sounding references to these standards or to the soldier’s honor which was attached to similar devices in Roman times; but it is not far-fetched to suppose that the standards came to have some such significance to the men who marched under them.

Chariotry was the elite branch of the service; it led the charge, to clear the way for the foot soldiers behind. The infantry was made up of several types of soldiery called by different names, the meaning of which is not always clear to us. There seems to have been a distinction between veterans and new recruits, and perhaps also between volunteers (career army types) and conscripts. The “Braves of the King” sounds like a select group, and in at least one case their commander led the attack on the besieged city. Then there were military specialists: the heralds, who may have acted as dispatch runners, carrying the general’s orders to various parts of the field; the scouts, mounted on horse back (there was still no cavalry as such); and a whole battery of scribes. Thutmose III had an officer who was responsible for the royal quarters at night when the army was on the march, and presumably transport, supplies, communications, and other support groups were also organized.

We have some references to and depictions of naval battles. In the twelfth century Egypt was attacked from the north by a loose confederation of tribes we know as the Sea Peoples, and Ramses III met them on land and on water. Even here, hand-to-hand combat, ship-to-ship, was the rule, and the weapons were the same.

Some of the male slaves captured in the Asiatic and Nubian wars were allowed to serve as soldiers, thus earning their freedom, and as time went on such mercenaries became an important part of the military forces. Another originally foreign group of soldiers were never slaves; they became not only thoroughly Egyptianized but an elite corps. These men were Nubians, perhaps related to the warlike C people who gave the Middle Kingdom pharaohs such a hard time during their conquest of Cush. A delightful group of model soldiers found in an Eleventh Dynasty tomb shows that by that period they were already an integral part of the armed forces; the black men are as well armed and bear themselves as proudly as their brown-skinned counterparts from the same tomb.

During the Second Intermediate Period a large group of this warlike people moved into Upper Egypt. They were allied with the hated Hyksos, who occupied much of northern Egypt; this put a nasty squeeze on the princes of Thebes, who were, if we can believe the propaganda texts that have survived, chafing under Hyksos arrogance. Eventually the Thebans drove the Asiatics out and pursued them all the way to the Euphrates—with, it is now believed, the active assistance of Nubian troops. However, it was not long before the Nubians ceased to be a separate ethnic entity. Their distinctive graves, some so shallow that they have given the name “pan-grave people” to this group, disappear at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty—not because the Nubians left the country, but because they adopted the customs of their new nation. The round Nubian huts became Egyptian houses, the graves turned into tombs, and the “pan-grave people” became the famous Medjay, skilled bowmen and soldiers who served Egypt for centuries as scouts, policemen, and guards. After a few generations they might be assimilated physically as well as culturally, for the Egyptians, what ever their other sins, were never stupid enough to discriminate against people on the basis of skin color. The Medjay were first-rate fighting men, and that was what counted with Egypt’s warlike pharaohs of Dynasty XVIII.

We have fairly detailed descriptions of two ancient battles, and as I said, neither indicates much foresight on the part of the Egyptian general, who was, in theory, the king. The cities attacked were in the contested territory of Syria-Palestine, which was sometimes controlled by Egypt and sometimes by the Hittites of Anatolia or the Mitannian kingdom of north Syria. In both cases the assault was to be made on a walled town, and in both cases the enemy did not wait to be assaulted, but sallied forth to meet the Egyptians. Thutmose III, who was attacking Megiddo, had the nerve to lead his army along the most direct path to the city, which happened to be a narrow mountain road over a pass. The obvious idea of an ambush does not seem to have occurred to the enemy; or possibly the road was not as dangerous as Thutmose’s official report makes out, since its aim is to show the king’s daring contrasted with the cautious timidity of his staff. And, of course, a rash act that succeeds is daring, while one that fails is just stupid.

Ramses II, at the battle of Kadesh, did something equally rash, but in his case it turned out to be stupid. Kadesh, on the Orontes River, was then allied with the Hittites. In the first place Ramses took the unsupported word of two casual passersby that the main enemy force was a long way off, which wasn’t the case. In his manly zeal Ramses had outstripped two of the four divisions of his army, so that half his troops were too far behind to be of any use to him in case of trouble—which he promptly found. The activities of the enemy commander—who is referred to, in the engaging Egyptian fashion, as “the Fallen One of Khatti”—suggest that elementary notions of strategy (or is it tactics?) were not unknown. If he did send out the enterprising liars who told Ramses the fairy tale about his whereabouts—Egyptian texts say he did—he was a better strategist than Ramses. He followed it up by leading his troops out behind the opposite side of the city, hidden from the approaching Egyptians; he swung them around in a circle and hit, not the first division, which was closest to the city, but the second. This division, that of Re, was caught completely unawares, and the enemy commander scattered it. He then attacked the first division, that of Amon, which had set up camp with its king.

From that point on the story becomes a trifle misty. One version explains that immediately before the attack the Egyptians had captured two more enemy scouts (were they always sent out in pairs, or is this just for symmetry?), who admitted, after some strong persuasion, that the Hittites were close at hand. This bit of information, which would have been useful at an early stage, came too late. Ramses was still trying to decide what to do about it when the enemy struck. Egyptian versions attribute the survival of the king to his own valor in holding off, single-handedly, the whole enemy army until reinforcements arrived. Ramses II has never inspired much confidence in me, so I have serious doubts about this version. However, reinforcements did arrive in time to save the king’s skin—not the belated regiments of Ptah and Set, but another group referred to as the Na’arn, who seem to have been high-ranking Egyptian troops sent to Phoenicia by sea, and who came overland to Kadesh by another route.

It is possible to make a coherent, consistent narrative of these events, but I prefer not to do so since I don’t believe the Egyptian version. The arrival of the Na’arn, whoever they were, literally in the nick of time, seems a little too fortuitous considering the distances that were traveled and the difficulty of communication between them and Ramses. Then there are those two sets of spies….

On the other hand, if Amon was watching over his “chosen people,” that explains everything.

Thutmose III had less difficulty than Ramses, perhaps because his opponent was not so good a strategist as the Fallen One of Khatti. Thutmose got his army out of the pass without incident and thus was able to conduct his battle in approved style. The enemy was waiting, and both armies proceeded to arrange themselves in battle order, on a wide plain which gave everybody room to spread out. The trumpeters then sounded the charge….

There are war trumpets in several museums, but the most famous are those of Tutankhamon. One was of silver, the other of copper alloy. The funnel-shaped bell was attached to a slender tube almost two feet long. They were in such good condition that the temptation to play them was irresistible. In a 1939 BBC broadcast a bandsman blew several blasts on the silver trumpet before it unexpectedly shattered. One can only imagine the poor man’s consternation—especially since, as some critics have suggested, it was the insertion of a modern mouthpiece that caused the disaster. What did it sound like? Raucous, according to some; but I’ve listened to the recording, and the very idea that I was hearing an instrument that had been silent for over three thousand years made chills run up my spine.

To resume: the trumpets sounded, and off went the chariotry, led by Thutmose, at a mad gallop, kicking up stones and dust and making a considerable racket—springs crackling, wheels rattling, and everybody yelling. The mounted archers began to shoot, though how they could have expected to hit anything I don’t know; I suppose if the enemy was thickly massed they were bound to hit something. The enemy front line also consisted of chariotry, at least in the Asiatic territories; the two sets of chariots engaged, or one swept the other away; at any rate, the field was now cleared for the infantry, who came running up waving their axes, clubs, swords, and daggers. Eventually, in the Egyptian narratives, the enemy broke and fled—to their city, if they had one close at hand. A siege usually followed, and it was sometimes maintained until the enemy was starved out. Thutmose III, who was a busy man and had a lot of cities to conquer, took some of them by storm, using siege ladders and sappers to undermine the walls. Judging from his accounts, clemency was the order of the day, not a brutal sack of the conquered city. Since it now belonged to Pharaoh, with all its people and their possessions, the common soldiers could not be allowed to loot it. Perhaps this is why the poor soldier in our quotation had to carry the Syrian woman instead of leaving her to die by the wayside, but it would be nice to think that compassion had something to do with it.

Some of the conquered peoples chose or were chosen to serve the conquerors as soldiers rather than slaves. They could earn freedom and promotion thereby. No doubt the Egyptians were glad to have mercenaries doing their fighting for them. The armies of the Late Period came to be made up more and more of foreign mercenaries. Such men, like the famous Medjay, had served Pharaoh at an earlier time, but not until the later New Kingdom was a majority, perhaps, of the army made up of men whose only loyalty to Egypt came through their pay. What, if anything, this had to do with Egypt’s later failures on the field of battle no one can say for sure, but it may have had its effect.

The army coup d’état is a familiar occurrence in some areas of the world; as far back as the Year of Four Emperors, when the Roman legions nominated their own Caesars, the army has been an entity capable of wielding political power. It is only natural that we should look for the same thing in Egypt after the rise of the professional army, and since we are looking for it, naturally we find it. At the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, after the fall of the royal house of Amarna, the throne of Egypt was held successively by two men who had, among other titles, that of “general.” Harmhab served under Tutankhamon and perhaps under Akhenaton as well. By the time he assumed the Double Crown there was probably no man alive who had a legitimate claim, by birth and blood, to the kingship, but this does not explain why it was Harmhab, and not some other commoner, who won it. Harmhab had no surviving sons, and his successor was probably another army man, perhaps an old buddy of Harmhab’s. It’s all very confusing, but confusion is compounded by the fact that both Harmhab and Ramses were other things besides generals.

A similar case occurred at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, when a man named Herihor turned up in Thebes with the resounding titles of Vizier of Upper Egypt and High Priest of Amon and removed—rather politely—the reins of power from the last of the feeble Ramesside kings. So for a long time the history books reported that the increasing power of the priesthood of Amon culminated in a theocracy which ruled at least part of Egypt. Then somebody noticed that before Herihor got to be high priest he was Viceroy of Nubia and Commander of the Army. The religious coup became a military coup, and once again, as in the case of Harmhab, the army got the credit for controlling the state.

With all deference to the distinguished scholars who have supported this interpretation, I cannot help but feel that it oversimplifies the ancient Egyptian scene and forces modern viewpoints on a culture to which they were not applicable. The army, the bureaucracy, the church, and the state—these categories were not as clear-cut in Egypt as they are today. We do not know how Harmhab and Herihor seized power, or which of their many titles conceals the real source of a strength great enough to enable them to mount the throne of the Two Lands. Their success may have been due to their control of the army, or to their high rank—or, for all we know, to their beautiful brown eyes.