Charles the Bald attacked Brittany many times, always lost, always conceded territory.

Border disputes between Brittany and the Franks had erupted into open warfare in 845, when Nominoe, the Breton ruler, died in March 851 and Charles invaded Brittany. His force included Saxon infantry. He was met by Nominoe’s son Erispoe by the River Vilaine near Redon. Charles was defeated. Among the dead were Hilmerad count of the palace and Count Vivian the chamberlain. Charles tried to retreat, in cowardly fashion according to the Bretons. Charles’ rearguard was attacked. Afterwards he recognised Erispoe in Rennes and Nantes, in return for homage.

Kings took their treasuries on campaign with them and the booty taken from a defeated host could therefore be sumptuous. The supply trains captured from the usurper Gundovald in 585 included much gold and silver. The career of the luckless but fascinating Charles the Bald once again provides illumination. On one occasion, he temporarily lost three crowns and some fine jewellery whilst marching against the Vikings. The Bretons captured much of his royal finery after Jengland, and Charles again had his baggage, and that of the traders following his army, taken by the victorious East Franks after Andernach in 876.

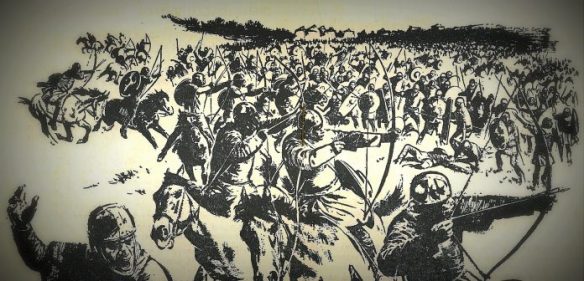

The success of Breton armies in resisting Frankish overlordship in the Merovingian and Carolingian periods – and indeed major victories over Charles the Bald at Balon in 845 and at Jengland on the river Vilaine in 851 – make it clear that Breton rulers must have been able to raise armies efficiently, and that those forces were very effective on the battlefield. Their military value is further suggested by the fact that Frankish aristocrats were happy to make use of Breton forces during the civil wars of the ninth century. Part of the Breton success was based upon their way of fighting, striking hard with highly mobile cavalry. This was a distinctive way of fighting which Frankish armies found difficult to counter. Military organisation in Brittany is largely obscure throughout the early medieval period but in the ninth century more detailed snippets of information begin to appear. Much that can be discerned suggests common features to those found in Francia.

Royal and aristocratic households made up the core of armies. Regino of Prüm records one aristocratic Breton warband as 200 strong. As elsewhere the junior members of retinues were called pueri, and it seems that youths acquired their military education in these followings. Aristocrats, as in Francia, cemented their ability to take part in warfare by making gifts in exchange for weapons and, especially, horses. A man called Risweten demanded a horse and a mail shirt in return for dropping his claim to an estate held by Redon Abbey. 178 The monks offered him 20 solidi as a cash alternative, which he refused, with fatal results – being killed at Jengland. As in other polities, the Breton rulers seem to have made use of major religious establishments to furnish military contingents, and act as bastions of princely power.

Whether, or rather in what ways, the Breton rulers, the principes (princes) had the right to exact military service from their subjects is unclear. There are references to dues exacted upon the free population, including tribute and census (tax), opera (works) and angaria (carriage duties). Davies cogently argues that the latter may, by the ninth century, have been levied as a form of rent rather than actually in labour services, though that might have been the case earlier within our period. Interestingly, the ruler, or other potentate, had the right to pasture his horses upon the land. That horses are often coupled with dogs in references to this imposition suggests that it was primarily concerned with hunting but we should remember not only the apparent centrality of horses to Breton warfare but also the fact that hunting was one of the most important forms of military training. There may thus have been some duty to perform military service extracted from some of the free population. The Acts of the Saints of Redon states that in 851, before his victory over Charles the Bald, the Breton princeps, Erispoe, `ordered his army to be prepared, and commanded that everyone get ready and advance before him across the river Vilaine. At once all the Bretons rose from their homes.’ This at least sounds like the calling out of an army according to some sort of understood military obligation. However, exactly what sort of military obligation hinges on the translation of the word sedes (literally `seats’). If, as here, it is translated as `homes’ it sounds like a general levy. Sedes, though, also means political bases – seats of power – and if the word is translated in this way the statement might imply that `all the Bretons’ meant the same thing that `all the Franks’ meant when used by some Frankish writers: `all the powerful Bretons’. This would imply an army drawn from aristocrats and their retinues. It seems that machtierns (locally powerful people) might occasionally fight, or at least take part in the army’s activities. One, like Ripwin, bought a horse from a priest in return for land, and as with that case it seems likely that this purchase was related to the ability to perform military service. Indeed, horses feature reasonably often in the prices paid for land.

The relationships between the Breton principes and their aristocrats were complex. The latter were landowners with access to resources and dues perhaps not very much less than those of the rulers, although how they related to the small, local village communities is difficult to ascertain. The major aristocrats do not emerge very clearly from the best source for Breton social history, the Redon cartulary. The power of the élite combined with the nature of the physical geography of Brittany to make Breton politics complex. Smith’s careful analysis suggests that the dynamics of the political relationships between the Breton rulers and the Carolingian kings and emperors on the one hand and their own magnates on the other were not dissimilar to those of the relationships between aristocrats and their rulers within polities. The Breton principes drew prestige and legitimacy from association with the Carolingians; the latter could derive kudos in Frankish politics from the claim that the Breton princeps had submitted to them. These relationships, and the frequent negotiation and renegotiation of their terms, were not without conflict however. Breton-Frankish and intra-Breton politics frequently involved fighting.

BALLON, 22 November 845

Forces: c 1,000 Breton; c 3,000 Frank

Location: Redon, Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany

Franks were defeated at Ballon. Defeat of Charles the Bald by the Bretons under Nominoe, Louis the Pious’ missus dominicus. A Breton dispute led Charles to intervene with a small force. It was a `rash attack’. Some of his men deserted. In marshy country at Ballon, north of Redon, Charles was beaten and retreated to Le Mans, barely escaping. Nominoe’s victory ensured Brittany’s independence of the Frankish king, later recognised by treaty. Charles was acknowledged as overlord and Nominoe as dux in Brittany.

Charles quickly assembled an army of around 3,000 men. Nominoë’s men were probably much fewer in number, comprising mostly a highly-mobile light cavalry.

Nominoë lured the king into marshland at the confluence of the Oust and the Aff between Redon and Bains-sur-Oust, near Ballon Abbey – hence the name of the battle. The Bretons were then able to exploit their knowledge of this treacherous wetland territory.

Details of the events of the actual battle are sketchy. Reports simply state that Charles was defeated. According to the Annals of Saint-Bertin:

“Charles had recklessly attacked Gallic Britain [Brittany] with limited forces, slipping up by a reversal of fortune…”

According to First Annales de Fontenelle:

“The Franks entered Brittany and engaged in battle with the Bretons, November 22. Helped by the difficulty of the wetland location, the Bretons proved the better.”

JENGLAND, August 851

Forces: 1,000 Breton; 4,000 Frank

Location: Grand-Fougeray, Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, France.

In 851, the Bretons won a further decisive victory at Jengland, which was instrumental in securing virtual independence for Brittany throughout most of the medieval period.

In August 851, Charles left Maine to enter Brittany by the Roman road from Nantes to Corseul. The king arranged his troops in two lines: at the rear were the Franks; in front were Saxon mercenaries whose role was to break the assault of the Breton cavalry, which was known for its mobility and tenacity.

In the initial engagement, a javelin assault forced Saxons to retreat behind the more heavily armoured Frankish line. The Franks were taken by surprise. Rather than engage in a melée, the Bretons harassed the heavily armed Franks from a distance, in a manner comparable to Parthian tactics, but with javelins rather than archers. They alternated furious charges, feints, and sudden withdrawals, drawing out the Franks and encircling over-extended groups.

After two days of this sort of fighting, Frankish losses in men and horses were mounting to catastrophic levels, while the Bretons suffered few casualties. With his force disintegrating, Charles withdrew from the field during the night. When his disappearance was noticed the following morning, panic seized the Frankish soldiers. The Bretons quickly raided the camp, taking booty and weapons and killing as many fugitives as they could.