On 1 April, 536, three months after Sicily had fallen to the victorious army of Belisarius, Justinian issued a law on the administration of the province of Cappadocia. Its provisions do not concern us, but its codicil does, for there Justinian refers both to the cost of his wars, and his hopes:

God has granted us to make peace with the Persians, to make the Vandals, Alans and Moors our subjects, and gain possession of all Africa and Sicily besides, and we have good hopes that He will consent to our establishing our empire over the rest of those whom the Romans of old ruled from the boundaries of one ocean to the other and then lost by their negligence.

To us, with the advantage of hindsight, there is a whiff of irony to Justinian’s prose. But in 536, the push to renew the Roman Empire was still going well, and success seemed to justify the cost of it all.

The Vandals in North Africa had provided an opportunity. In Byzacena, too close for comfort to their estates within the Sortes Vandalicae, they had lost a battle to the Moors. The Vandal king, Hilderic, the grandson of the emperor Valentinian III, was no warrior but Justinian had reason to like him. He had ended the maltreatment of the Catholics, sought a rapprochement with the emperor and had consequently alienated the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy. In mid-June, 530, he was deposed in a coup d’état led by a great-grandson of Gaiseric, Gelimer, who was considered an able soldier and whose Arian sympathies were not in doubt. Justinian promptly remonstrated, but Gelimer turned a deaf ear. He told Justinian, as one king to another, not to meddle. Justinian was understandably irritated, and there was an influential lobby of merchants, African churchmen and dispossessed landowners in Constantinople to play upon his sense of grievance. Hilderic had aroused expectations, and now he was fallen, they pressed Justinian to avenge him.

But the consistory was dismayed. The Persian War had just come to a conclusion, the `Endless Peace’ was costly, and the treasury empty, and most of all, the councillors remembered the disastrous expedition that the emperor Leo had dispatched against Gaiseric. But only the praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian dared speak against the venture, according to Procopius, who was no friend of John’s, but here calls him the `most daring and clever of all his contemporaries’. John felt no romantic yearning to recover the western provinces. He might have won over Justinian, except that Christian faith intervened. One account has it that a bishop from the eastern provinces appeared, and reported a dream which promised success if the emperor would preserve the Christians of Africa, and another story relates that it was the African martyr Laetus, slain in a Vandal auto-da-fé in 484, who came to Justinian in a dream to urge him on. The African lobby had its way.

The field army that was readied for the expedition numbered about 18,000 men, 10,000 of them infantry, who needed 500 transport ships with 30,000 crewmen, most of them Egyptians or Ionian Greeks. To convoy them, there was a flotilla of 92 fast warships (dromones) with 2,000 fighting men as rowers. The generalissimo was Belisarius, whose wife Antonina accompanied him, and his immediate subordinates were Dorotheus, commander of the troops from Armenia, and Belisarius’ domesticus Solomon, a eunuch castrated by accident rather than intention. Procopius, our chief source for the expedition, went along as a member of Belisarius’ staff.

Just before departure, the Byzantines had two strokes of luck. A Roman Libyan named Pudentius led a revolt in Tripolitania, and in Sardinia, a Gothic retainer named Godas, whom Gelimer had placed in charge of the island, rebelled and sought Justinian’s aid. Gelimer had to let Pudentius be, but he was anxious to reclaim Sardinia, and dispatched his brother Tata with 5,000 men and 120 ships – probably the whole of his effective fleet, for as it turned out, he offered no resistance at sea to Belisarius. The Vandals seem to have been completely unaware of the threat in store for them.

About the time of the summer solstice of 533, the Byzantine fleet anchored off Julian’s harbour on the Sea of Marmara within sight of the Sacred Palace, received the patriarch’s blessing and set sail. The voyage to Africa was to take more than two months. The rift between the Vandals and the Ostrogothic kingdom served the imperial interests well: Amalasuintha provided a market in Sicily for Belisarius’ army. It was in Sicily too where Belisarius discovered that the Vandals did not expect an invasion. Their ignorance is extraordinary, for news travelled well enough over the trade routes, and the fact that no forewarning had reached them demonstrates how separate the world of the Arian Vandals was: they had little contact with traders from the eastern empire, and regarded them with suspicion. Procopius describes how he went to Syracuse to glean what intelligence he could, and there he met a childhood friend from Caesarea whose merchantmen journeyed regularly to Carthage, and a slave agent of his who had come from Carthage only three days before had reported that the Vandals anticipated no danger: their best troops had sailed with Gelimer’s brother to suppress the revolt in Sardinia! Procopius relates how he led the agent down to his boat at the waterfront, and hijacked him off to the roadstead where the fleet lay at Porto Lombardo, and there the slave repeated his story to Belisarius. It was welcome news. It helped dispel the gloom occasioned by the death of Dorotheus, which had only just happened.

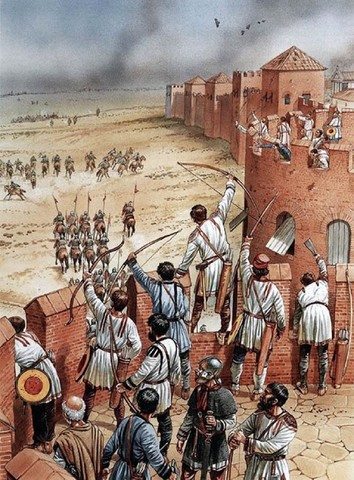

At the end of August, the army disembarked along the east coast of Tunisia, at Caput Vada (mod. Ras Kaboudia), some 200 kilometres south of Carthage. It built a stockaded camp, and chanced upon a stroke of luck: as the soldiers dug the moat, they struck a spring of fresh water sufficient for both men and pack animals. It was a good omen. From Caput Vada, the army proceeded warily towards Carthage. Belisarius allowed no pillaging; his war was pointedly directed against the Vandal occupiers of Roman Africa, not against the Roman inhabitants.

The fleet had sailed with the patriarch’s blessing and the promise voiced by the unnamed bishop who had provided the compelling argument for the Byzantine invasion. But thus far it was no anti-Arian crusade. Belisarius’ mission was to free Africa from a tyrant who had dethroned and imprisoned its rightful king, Hilderic. Justinian had provided Belisarius with an open letter to that effect, which Belisarius in turn gave to an overseer of the public post who had defected, with orders to broadcast it. As the army advanced, Belisarius was careful to maintain discipline and allow no looting that might antagonize the civilian population. And he took no chances. John the Armenian led a vanguard of 300 of Belisarius’ bucellarii some 4 kilometres or more in front of the main army, and on the left there was a company of 600 Bulgars, all mounted archers. On the right was the sea, where the fleet kept pace with the army.

Gelimer was caught unawares. He was staying at a royal estate in Byzacium when he learned of the Byzantine landing. But he reacted swiftly. He sent word to his brother Ammata in Carthage to kill Hilderic and his followers, who were imprisoned there, and to order his men to action. His strategy was sound enough. He planned to trap Belisarius in a natural defile at the tenth Roman milestone from Carthage. Ammata was to attack from the front, and himself from the rear, while another brother, Gibamund, would circle around and attack from the left. The action at the Tenth Milestone (Ad Decimum) was a battle of mounted troops, for Belisarius’ infantry remained in camp, and that was where the Vandal strength lay.

But the plan went awry. The Vandal scouts made contact with the Byzantine army while it was still about 45 kilometres from Carthage and for four days the two armies continued a wary advance to the locale of Ad Decimum, which is now covered by the northern suburbs of modern Tunis. The battle took place on 13 September, which was the eve of the feast of St Cyprian, but instead of the concerted effort Gelimer had planned, it was a series of isolated engagements. Ammata left Carthage too soon without his whole force, and he was defeated and killed by John the Armenian. Gibamund’s force fled and Gelimer himself, unmanned by grief at the discovery of his brother Ammata’s body on the battlefield, threw away his one chance for victory.

The road was open to Carthage. The city walls had been rebuilt in 425, in the last years of Roman dominion, but the Vandals had neglected them and the city could not stand siege. The populace welcomed the victors. Belisarius was careful to keep his army under firm discipline: he allowed no violence that might have alienated popular opinion. The Byzantine fleet sailed around Cap Bon and most of the ships preferred the Bay of Utica as an anchorage instead of the small harbour of Carthage known as the Mandracium. The victory had given the navy a safe haven just as the sailing season came to an end. The victory also decided the Berber sheikhs who had been waiting to see which side would win; now they sent envoys to offer allegiance to Justinian and ask for imperial investiture in return.

On 15 September, Belisarius entered Carthage, took possession of Gelimer’s palace in the emperor’s name and sat upon Gelimer’s throne. Gelimer had ordered a banquet prepared to celebrate the triumph he anticipated and now Belisarius and his officers feasted on it. Meanwhile, at St Cyprian’s basilica, the Arians fled, and for the first time in two generations, the Catholics celebrated the festival of the martyr Cyprian there, only one day late.

In the meantime, the Vandal expeditionary force which had suppressed the revolt in Sardinia returned, and Tata rejoined his brother. Gelimer moved on Carthage, but although Belisarius had not yet had time to complete repairs on the walls, and the city might have fallen easily enough to an enemy equipped with a siege train, the Vandals were horsemen, and the best Gelimer could do was to blockade the city by land and cut its great aqueduct. He also tried to contact the Arian troops in Belisarius’ army and win them over. The Arian clergy had for the most part fled Carthage along with the Vandals, but thus far, the anti-Arian character of the Byzantine expedition had been very low-key. It seems that Justinian thought initially that the Arian clergy could be integrated peacefully into the Catholic hierarchy, and changed his mind later only under pressure from the African bishops seconded by the pope. At this point, Gelimer’s attempt to tamper with the loyalty of the Arian troops came to nothing, but Belisarius took it seriously.

Some three months after the victory at the Tenth Milestone, which gave the Byzantines the city of Carthage, the decisive engagement took place that ended the Vandal kingdom. The Vandals had encamped with their wives, children and treasure about 30 kilometres from Carthage, at a place called Tricamarum which was protected by a small stream. The actual site is unknown, but probably it commanded the main road to Numidia. The Vandals apparently neglected to fortify their camp; their earlier defeat had not taught them prudence. The Byzantine vanguard under John the Armenian with all but 500 of the cavalry made contact with the enemy first, and camped close by, waiting for Belisarius to come up with the infantry and the rest of the horse. But the next day near noon, the Vandals drew up a battle line behind the stream, and repelled two feints against their centre led by John the Armenian, but without moving from their defensive position. But the third charge resulted in a fierce struggle along the whole front. All the Byzantine cavalry moved in and joined battle (Belisarius had joined the vanguard with his horse just as the action began, leaving the slower infantry to catch up). The Vandal centre sagged, Gelimer’s brother, Tata, fell fighting and the rout began. At this point, the two companies of Bulgar mounted bowmen in Belisarius’ army, whose loyalty was precarious and who were ready to swing over to the victor once they perceived who he would be, joined in the pursuit, and the Vandals fled to their camp.

Now, towards evening, the Byzantine infantry came up, and Belisarius advanced against the Vandal camp. Gelimer’s nerve broke. He mounted his horse and fled, and as soon as his departure was known, the Vandals fled after him, leaving a great wealth of booty behind them. The Byzantine troops abandoned all order and turned their attention to plunder, for they were all penniless men, and here were the riches of Vandal Africa before them for the taking. Had the Vandals rallied and counterattacked, they must certainly have won the day. But Gelimer was galloping along the road to Numidia.