Herodotus states that it took a full month for the completion of the crossing into Europe and then another three months before the Persian took Athens. The distance from the Hellespont to Athens is, however, just eight hundred and fifty kilometres (about 530 miles). This means that with the frequent halts for the pack animals to recover and for the various reviews of the land and sea forces an average daily march of a maximum of perhaps fifteen kilometres (10 miles) is indicated and probably less on most days. The slow rate of the advance had much to do with the size of the forces involved and the number of camp followers, but Xerxes seems to have also wanted to display his power to these new subjects who, says Herodotus (Herodt. 7.44–45) suffered greatly from the financial burden placed on them for entertaining the king and his immense entourage. The importance of the fleet in supplying the land forces cannot be underestimated and was probably high on the agenda of the deliberations among the Athenians and the Pelponnesian Greeks about what was the effective means of disrupting Xerxes’ advance to such extent that he would have to withdraw from his objective. Inflicting damage to the Persian warships and merchant shipping therefore became a priority and the place best to achieve that result was thought to be Artemisium at the northern end of Eubeoa. The combined fleet of the Hellenic League was sent north to intercept the Persians moving south along the coast. The command was given to the Spartan Eurybiades but Themistocles may be identified as the main architect of the strategy. To delay the Persian land forces long enough to cause maximum disruption to the accompanying fleet, another army was sent under the command of Leonidas, one of the Spartan kings to hold the pass at Thermopylae on the mainland opposite Artemisium.

Herodotus gives precise figures for the pass (7.175–177) and had plainly visited the site, although he does not claim to have been there. He states the road that ran through Thermopylae in Trachis was just 16 metres (50 feet) wide. It was a coastal road rather than a gorge as at Tempe with high cliffs on the left looking north and the sea to the right. In some place both north and south of Thermopylae the way was even narrower and barely sufficient for a single wagon to pass safely. This seemed an ideal spot to make a defence where superior numbers would count for less, and it was only when the Greeks arrived there that they discovered a major Achilles’ heel in their strategy, which was a mountain track that would be used by the enemy to attack defenders along the road from the rear. This revelation seems remarkable and hardly credible if the southern Greeks were joined by citizens from nearby communities as Herodotus states. His figures for the Greek force are also specific: the ‘official’ total was three hundred Spartiate hoplites (the full Spartan citizens), five hundred from Tegea, five hundred from Mantinea, one hundred and twenty from Arcadian Orchomenus, one thousand from the other communities of Arcadia, four hundred from Corinth, Phlius contributed two hundred, Mycenae eighty. These three thousand two hundred from the Peloponnesian League were accompanied by four hundred Thebans and seven hundred citizens of Thespiae and at Thermopylae were joined by one thousand Locrians, a thousand Melians, and roughly a thousand Phocians. The overall number of hoplites was seven thousand two hundred but there would also have been almost the same number of light armed troops not to mention the non-combatants and camp followers. There is no mention of any contribution of troops from Athens or Plataea.

Later Herodotus (7. 215) gives some of the history of the use of this ‘secret path’ in former times by the Melians and Thessalians. This track was hardly a best kept secret! It also illustrates that this was a known weakness in any attempt to hold Thermopylae or that the southern Greeks were really extremely careless in their strategic planning. Themistocles who is usually credited with being the architect of Xerxes’ downfall and a tactician of genius was surely aware of such an alternative route, which Herodotus reveals to have been quite a straightforward route to tackle, beginning in the valley of the River Aesopus (7.215–218). Therefore, it can probably be assumed at the root of the description of what was ultimately a glorious failure for the defenders are some negative impressions about Themistocles and praise instead for Spartan courage on land. The Phocian contingent offered to guard the track, but Leonidas must have known from the time he arrived at Thermopylae that at best his role would be of a brief delaying nature. There cannot have been any thought at all of a victory on land against the Persian forces at this stage, although Herodotus suggests that the choice of Thermopylae had much to do with limiting the use of enemy cavalry (7.177) and that some use could be made of an existing but dilapidated defensive wall that the Phocians had erected many years before in anticipation of an invasion by the Thessalians (7.176).

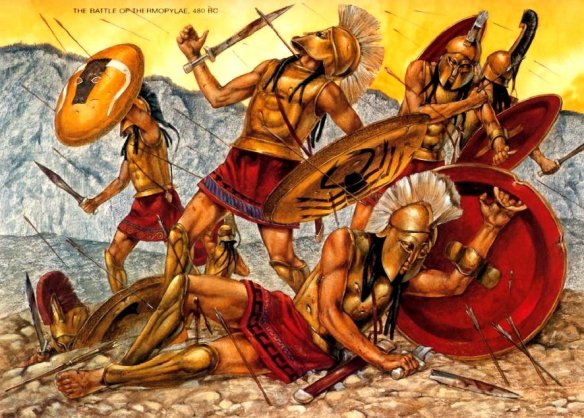

The Greeks had probably been present at Thermopylae for some days and although this force consisted of some well-trained hoplites in terms of numbers – perhaps ten thousand in all – they posed no real threat to the Persians who ought to have been able to sweep them aside. Xerxes clearly recognized the problem of forcing a way through the defenders on the coastal road and waited four days (Herodt. 7.210) for the Greeks to retreat in safety. On the fifth day by which time he was exasperated he ordered an attack with Median and Cissian troops but when these had suffered severe losses they were replaced by the king’s own Persian guard known as ‘The Immortals’. These too were equally unsuccessful against the Greek forces. On the next day, events repeated themselves and the Persians were repulsed with heavy losses. It was at this point that a certain inhabitant of Trachis named Ephialtes came to the Persian camp in the hope of a reward for telling of the existence of a track through the mountains that would allow the Persians to outflank the Greeks. Xerxes was delighted and sent off a column of troops after nightfall. At daybreak the Persians had arrived at the spot where the Phocians were on guard. These were quickly scattered – a half-hearted defence seems implicit in the text – and these hurriedly brought the news that the Persians would shortly be attacking from the southern end of the pass. The Spartan king instructed most of the Greeks to leave because, says Herodotus (7.220), most were unenthusiastic about facing certain death, although he also notes that some claimed that many of the Greeks simply left in a panic. Neither claim is truly appropriate since Leonidas would have been able to command his Peloponnesian allies to remain if he had wanted them to do so while it was Boeotian troops that actually stayed. It is therefore more likely that he dismissed his allies in order that they would be not be lost to the general cause while the Spartan force was to delay the enemy as long it could. This of course can hardly have been for more than a few hours especially since the Spartans are said to have abandoned the defensive walls in preference to a more open position. The day would have ended long after the Greek defeat. Twenty thousand Persians are said to have been killed. Most of the Thebans surrendered and were branded as slaves. The entire Spartan force of one thousand and the seven hundred hoplites from Thespiae were killed.

The fleet of the recently founded ‘Hellenic League’ had been sent to Artemisium, the place of the Artemision or the temenos of Artemis, on the north coast of Euboea, which allowed close contact with the land forces at Thermopylae. But here the sea also became a narrow channel (Herodt. 7.176), which would reduce the effectiveness of Persian numerical superiority. There were two hundred and seventy-one warships (Herodt. 8.2) with one hundred and twenty-seven triremes from Athens, and so the Greeks were heavily outnumbered. The choice of taking up a defensive position at this passage towards the more sheltered inner channel – the Euripus – between Euboea and the mainland is not remarkable, but it must certainly have resonated with an audience familiar with the geography that both land and sea forces took advantage of the landscape or here seascape to attempt to overcome the Persian threat. And if the Greeks could inflict some injury to their opponents’ fleet it immediately deprived Xerxes of command of the sea and made supplying his army more susceptible to disruption. Hence the Greeks would impose their own will where up to that point the initiative had lain with the Persians. In 490 before Marathon, on account of their victory at Lade three years before, the Persians controlled the sea lanes, but the vigour of especially the Athenians seems to have inspired a confidence to defeat this enemy navy. Perhaps they were spurred on by the fact that they had emerged the victors from the encounter at Marathon, although to what extent this apparent bravado is historically accurate and not written with the benefit of hindsight is difficult to judge. Herodotus possibly indicates that the Greeks were in fact far less enthusiastic about giving battle at sea than later became the tradition for when the fleet’s commanders heard of the approach of some Persian warships they immediately withdrew to Chalcis (7.183). Ten Persian triremes had been sent on in advance of the main body from Therme to reconnoitre and approached the island of Sciathos where there was a flotilla of three Greek ships. The latter turned tail but two were captured with their crews while the third beached at the mouth of the Pineus and the crew escaped overland into Thessaly.

From the Haliacmon River to Thermopylae the distance is roughly two hundred and seventy kilometres (about 170 miles) and it would have taken Xerxes’ army nearly three weeks to advance to a point where they came into contact with the defenders at Thermopylae. The army is reported to have departed eleven days earlier than the fleet (Herodt. 7.179), which seems like an accurate report. But Xerxes’ strategy had already begun to unravel because of a change in the weather. The fleet encountered no problems sailing south along the coast from the Thermaic Gulf and arrived between the town of Casthanea and Cape Sepias on the coast of Magnesia (Herodt. 7.183). There the earliest arrivals beached but the size of the fleet meant that there was no space and the majority of ships were forced to anchor offshore in eight lines (7.188). It should be assumed that the warships had precedence and were the quickest vessels in the fleet and so were brought ashore while the transports and the other ships lay at anchor. On the very next morning Herodotus claims (7.188) a storm blew up from the east known as a ‘Hellespontine Gale’, and those ships closest to the beach were brought ashore but those forced to ride out the high winds suffered many losses. Herodotus (7.190–191; cf. Diod. 11.12.3) claims four hundred triremes were reported as lost while large numbers of merchant vessels remained unaccounted for. The figure cannot be an accurate one and, as later in his narrative, is an attempt to reduce the Persian fleet to roughly six hundred warships at the start of the battle at Salamis. While a violent summer storm could wreak havoc with ancient shipping, mariners of the time would not have been taken entirely by surprise and so some exaggeration in the total losses may be expected from Herodotus especially since it does not appear to have been a cause of concern to the Persian command. The gale relented on the fourth day by which time Xerxes had issued instructions to take the war to the Greek fleet. Having observed the withdrawal of the Greeks south to Chalcis, two hundred Persian triremes were despatched to cover the southern end of the Euripus Channel perhaps aiming for Carystus or Eretria. The main body moved to Aphetae (Herodt. 7.193; Diod. 11.12.3) and arrived there two days after the Persian land forces had departed. Herodotus states categorically that the Persians arrived there early in the afternoon and that on the next evening the Greek force stationed at Artemisium went on the attack using a circle formation with their bows outwards. With this tactic, which prevented them from being rammed, they captured thirty Persian ships but how was this accomplished? The Greek ships were not in a position to grapple the enemy but they might have dashed out of the defensive circle and rammed amidships any encircling Persian vessel that came too close. However, these enemy warships were more likely to have been disabled or sunk rather than have been captured. That same night there was another violent storm that brought ashore the debris from the recent battle with the Greeks and seems to have unnerved the Persians at Cape Sepias. The following day the Persian fleet put to sea again and confronted the Greek fleet now reinforced from Chalcis but again when the sides broke contact it was the invaders whose losses are said (Herodt. 8.16) to have been severe but no figure is given except for the warships sunk by the previous evening’s storm as they made their way along on the Aegean coast of Euboea. On this second occasion the Greeks, although in a stronger position than in the first encounter, were still obliged to retreat to the safety of Salamis since reports arrived telling of the catastrophe at Thermopylae (Herodt. 8.21). Still, it is stormy weather as much as fighting that is noticeably the constant theme in the account of the battle of Artemisium, and which accounted for more casualties than the fighting itself. Herodotus ominously reports (8.14; cf. Diod. 11.13.1) that it was as if the deities, offended by Xerxes’ pride perhaps, were determined to reduce the numbers of the enemy fleet so that the Greeks would in future be more evenly matched.

Any detailed recollection of the encounter or rather series of encounters at Artemisium was quickly lost. Indeed as soon as the Greeks scored their great victories at Salamis, Plataea and Mount Mycale, all thoughts about the indecisive affair off the northern coast of Euboea ceased. Thermopylae remained as an example of heroism in the face of adversity and overwhelming odds, but the Greek inability to hold the Persian advance on sea before Attica could easily be suppressed. The defeat at Thermopylae happened when the Greek and Persians fleets were still engaged on what was probably a second day of fighting. They were warned by messengers of the defeat on land and that Xerxes was already advancing south. Tactics dependent on synchronized action between two forces were always a problem in antiquity and success could hardly be guaranteed, especially when one was on land the other on the seas. The battle at sea needed to be won so that Xerxes would think twice about venturing further into Greece, and this did not happen. Xerxes may have faced problems on land and on sea but he had accomplished his objective of penetrating the obstacles to an invasion of Attica and the Peloponnese. Still, a brief but curious interlude full of the supernatural intruded before the Persians occupied Athens their ultimate goal.

After forcing his way through Thermopylae Xerxes’ army marched south through Boeotia causing immense damage and devastation. While on the march the king’s attention was drawn to the fact that he was very close to Delphi, a place whose contents, says Herodotus (8.35), Xerxes was more familiar than he was with the contents of own treasury. Of particular interest to him were the treasures dedicated to Apollo by Croesus, former king of Lydia, whose kingdom had been conquered by the Persian king Cyrus in 545 BC. He ordered a force to attack and sack Delphi and to return to him with its treasures. There was perhaps another reason for the attack since Xerxes hardly needed the wealth of Delphi but he knew that recent oracular messages delivered especially to the Athenians urged the defence of Greece and promised victory against the Persians. The oracle regarding the defence of Athens by the employment of a wooden wall (Herodt. 7.141), which Themistocles had presented as a case for investing in the construction of a hundred new triremes as late as 483, would by then have been known well enough in Susa. The sack of Delphi and destruction of the temple of Apollo might have seemed an appropriate action to take after the victory at Thermopylae.

The Delphians were well aware of their danger and sought oracular advice of whether to hide the temple treasures or take them elsewhere for safe keeping only to be told that Apollo would look after his own possessions (Herodt. 8.36). The citizens of Delphi nevertheless were not convinced that the god would also look after them as well and so families were evacuated across the Gulf of Corinth to Achaea or into the mountains around Parnassus and Amphissa. As the Persian troops approached Delphi from the northwest, still the main route inland from Orchomenus, defence of the temenos lay in the hands of Apollo’s priest and just sixty volunteers. As the Persian troops reached the shrine of Athena Pronaia the priest noticed that at the temple of Apollo arms that were dedicated to the god were lying before his shrine. At the same moment it was claimed that loud thunder was heard and great boulders fell from the cliffs high above the Spring of Castalia crashed down and killing many of the attackers. Besides this two phantom giants were said to have emerged to fight with the Delphians who had taken advantage of this intervention by the god and scattered the invaders who fled. Later reports also spoke about two gigantic warriors – supposedly local heroes from ancient times – who also joined in the rout killing many of the Persian troops. If the attack took place at all, and there is considerable doubt about this since the political sentiment of many of the members of the Amphictionic council, which oversaw the management of the Delphic Games, second in importance only to those held at Olympia, had already joined the Persian cause, then a fortuitous earthquake, common enough in these parts, would have been a sure sign of the god’s displeasure. Historical the episode is not but here once again the narrative has that unlikely mix of fact and unreality that pervades Herodotus’ account of the campaigns to Marathon and Thermopylae.

The fame of Thermopylae unquestionably matches that of Marathon, and rather in the same way that the latter’s renown is constantly reinforced by the running of the ‘marathon race’ every four years at the modern Olympic Games, the former has remained in the public imagination through continued cinematic interpretations. The development of an elaborate modern myth takes its starting point from the epitaph to the dead Spartans for whom this was held up as the apex of not exactly famous victory but glorious defeat. Herodotus, of course, records the inscription and had almost certainly visited the scene of the fight and observed the memorial (Herodt. 7.228):

Oh stranger on the road announce to the Lacedaemonians that obeying their words we lie dead here.

Once here four thousand from the Peloponnese fought against three hundred times ten thousand.

The result of the engagement between the Greeks and the Persians at Thermopylae clearly provided another opportunity for propaganda and an entry into the historical tradition. But was it really like it was recorded by Herodotus and to what extent have modern versions altered the ancient accounts?

For such an apparently great victory Herodotus’ coverage of Marathon is remarkably brief (Herodt. 6.112–115) and is barely any longer than his account of the sack of Sardis at the start of the Ionian War (Herodt. 5.100–102). This brevity probably indicates that the writer was not in a position to retrieve any more than the barest outline of a military engagement, and that his own sources, whether oral or written, were almost completely deficient and that much of what he was obliged to provide his audience with therefore a gloss to cover this shortfall. And what Herodotus relates has long been recognized as both inaccurate and incompatible with any scientific study of the episode. He may wished to have bypassed any detailed account but could hardly ignore Marathon entirely; however, he was in possession of much more material for Xerxes’ invasion and that was where his main focus rests in the later parts of his history. The date of the battle of Marathon (mid-August 490) plainly illustrates the slow progress of the Persians and indicates that this was no lightning strike. The Persians must have left Samos only in May or June and did not arrive on Euboea until early August and so six to eight weeks were spent subjecting the Cyclades to their rule and ensuring a stable line of communications with Asia Minor. The planning up to departure had been meticulous and Datis and Artaphernes can hardly be criticized for poor management of the expedition up to their beaching at Marathon. However, the organization of the troops and especially of the cavalry detachments is open to censure for once landed there seems to have been insufficient attention to the possibility of a hard fight. It should also be remembered that the heavy emphasis on cavalry use indicates not a whim of Darius but that he had discussed the expedition with Hippias long before it set out or before the first preparations were ordered. This gives an insight into this ruler’s habit of consultation and being prepared to accept advice from specialists who knew the region and the inhabitants. The Persians might be forgiven for being over-confident following the ease with which the expedition had gone thus far, but they must surely have realized, especially with the presence of Hippias as adviser, that the encounter here would be much more fiercely contested. It was either this lax discipline or perhaps a decision to go forward to Athens itself without a fight at Marathon that proved the expedition’s undoing. The Persians may simply have decided that with the hiatus in the hostilities and the chance that the Athenians would not engage that they faced a better chance of outright victory by sailing without a further delay to Phaleron. This decision allowed them to be caught without their cavalry in a position for best utilization. The Persians clearly had well trained infantry and these were almost certainly outnumbered by their opponents, yet they did initially well in repulsing and turning the admittedly weakened Greek centre before falling into the trap designed by the Athenian commanders. Finally, the tenacity of the defence of Attica must have surprised the Persians after the ease with which they had taken the islands and especially much of Euboea. Hippias may well have given over an optimistic assessment of the reception the invaders would have received.

For the campaign to Thermopylae it is again the question of supplying an invading army and insuring an easy progress which dominates the narrative in Herodotus and later sources. Admittedly there is a great deal of fanciful and entertaining material about the hubris of Xerxes or the participation of the deity in saving his temple at Delphi or the role of oracles in foretelling defeat for Persian and triumph for Athens. As with the campaign to Marathon, the text has an almost eclectic mix of fact, pseudo-fact, and fiction, but remain the ingredients of a highly successful narrative composition. Its survival intact attested to that success! The defence of Thermopylae, for it was that rather than a battlefield in the true sense, seeing that two opposing armies were not on this occasion drawn up in the classical manner of infantry or cavalry drawn up as a centre and wings, and the tactic of encirclement being attempted by either side. The importance of holding Thermopylae is plain because the main north south route into Attica, Boeotia and the Peloponnese lay through this narrow one sided gorge. The road ran beside the sea to the left as one approached from the north with high overhanging cliffs on the right. There are others routes into Central and Southern Greece, for example via Amphissa to the north of Mount Parnassus but for an army of the size that accompanied Xerxes that was almost impassable so the Persians were forced to go by Thermopylae. And so the interface between sea and land in these campaigns continued as the protagonists regrouped after Thermopylae and Artemisium and events inexorably moved on to Salamis, Plataea and Mycale; but that is another story. And indeed the stage was set for the final showdown but the form those encounters took and the logistical problems that were overcome in undertaking such ambitious adventures were solved in the Persian expedition to Marathon and along the road Xerxes took to Thermopylae. But perhaps most important again in both Marathon and Thermopylae has been overcoming the problems of logistics for an army on the move, the placement of the battlefield in its geographical context and the affect the weather can have on the outcome of any military campaign.

Chronology

493/2 Mardonius satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia and Thrace.

492 (summer) Mardonius in Thrace where his fleet was destroyed by gales trying to round Mount Athos in the Chalcidice.

491 Datis and Artaphernes appointed to joint command of an expedition to Greece.

490 July Persians attacked and captured Carystos and Eretria on Euboea.

August Persian forces landed at Marathon and were defeated.

August Persians failed to land at Phaleron.

September Persians returned to Asia Minor.

487/84 Rebellion in Egypt against Persian rule.

486 Death of Darius. Accession of Xerxes.

483 Start of construction of a canal across the isthmus to Mount Athos.

481 Xerxes ordered the ‘double bridging’ of the Hellespont.

480 May Xerxes crossed the Hellespont.

May Themistocles at Tempe.

June Persian army and fleet in Thrace and Macedonia.

July Persian victory at Thermopylae, sea battle at Artemisium. Persians attacked Delphi.

September Persians defeated at Salamis.