Xerxes – Hellespont – 480 BCE by Peter Connolly

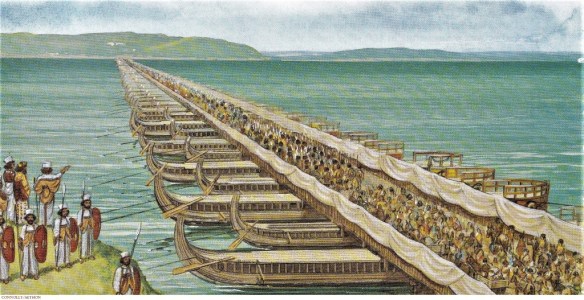

Still, it is extraordinary that Xerxes was able to dispose of about a thousand warships of trireme or pentekonter design that were deemed too old or ruinous, but were still usable for bridging the Hellespont. Besides these he also had in service another twelve hundred warships, mostly triremes of recent construction for his fleet. The disparity in the size between the two ship types indicates that if there were two bridges then the triremes placed beam to beam comprised one, the pentekonters beam to beam the other. The difference in height and width using the two types would have resulted in an unusable structure. The trireme with its five-metre beam was at least nine metres in height to take account of its three tiers of rowers, while the pentekonter was a much smaller vessel with a single line of rowers not that much shorter at twenty-eight to thirty three metres, with a beam of four metres, but its height was not much more than three metres. A bridge consisting of a haphazard combination of both types seems quite impossible. It has been argued that the Hellespont, which today has a depth in places of up to one hundred metres, was in antiquity about one and half metres lower at the Abydos to Sestos crossing. Yet it is also clear that the sea has retreated quite dramatically further south in the Troad; at Troy the citadel once at the beach is now five kilometres inland. If the channel further north had a lower level in antiquity then the crossing distance would also have been somewhat less than the seven stadia ascribed to it by Herodotus.

It is possibly fairest to conclude that as far as the bridging of the Hellespont is concerned that, although there are clearly invented elements in Herodotus’ account, the assertion that the channel was crossed by Xerxes seems irrefutable simply because it is stated so firmly. Still, it may well be that there may have been just one rather than two pontoon bridges available to Xerxes and his army for crossing the channel in the late spring of 480, and that the crossing was a combined operation using bridge and ferries. This seems plausible if only because of the waste of resources that building two bridges would have consumed. Thus one should not forget that quite explicit in Herodotus’ account is the glorification of Xerxes’ ambitions employed by the historian to elevate his subject’s pride so that the victory by the Greeks can be equally enhanced. Finally, Herodotus states (Herodt. 9.114) that when the Greek fleet arrived in the Hellespont in the summer of 479, by then victorious over the Persians whom they had fought and defeated on the beaches around Mount Mycale just across the Latmian Gulf from Miletus, ‘they found the bridges broken up’, but provides no further details.

Regarding Xerxes’ war fleet, Barker, for example, believes that Herodotus’ figure of one thousand two hundred and seven triremes (Herodt. 7.89) included those six hundred and seventy-four that had been used in the construction process of the bridge, hence leaving approximately another six hundred to accompany the invading army. However, as Wallinga has shown this will not do, and the six hundred ascribed to the Persian fleet in 481/0 is drawn from a comparison with the fleet of Darius in his Scythian expedition and the Persian fleet at Lade, but it is clear that Xerxes’ fleet was very much larger and meant to be greater than any employed in this region before. And indeed Herodotus is at pains almost to describe how Darius ordered the building of not just warships but also of other vessels (Herodt. 7.1) when he began to make plans for another attack on the Greeks in the aftermath of Marathon. Herodotus’ numbers are extraordinarily precise and he must have drawn these from an earlier source, perhaps one of the early Ionian writers of history who may have remembered details and recorded them. Xerxes’ fleet suffered considerable losses en route to Attica, especially at Artemisium (see below). Even if some of these were exaggerated by Herodotus to glorify the achievements of the Greeks there were still over six hundred ships in the Persian fleet at Salamis. Hence the starting total was not far from the figure given by the historian.

The total numbers in Xerxes’ army have also been the subject of apparently endless debate and while clearly there is again much elaboration in Herodotus’ narrative, the lowest possible totals for his army and navy make extremely impressive reading and as reports and rumours emerged about the numbers to the Greeks highly intimidating. The crews of even a thousand triremes add up to about two hundred thousand men and these were mostly rowers not expecting to be involved in land battles. This figure would not be much less if there a sizeable number of the smaller pentekonters in the fleet. The fleet moving in tandem with the army west from the Hellespont also had to beach at the end of every day’s progress for the ships’ hulls to dry off and for the crews to eat and rest. And this number does not take into account the huge number of civilian craft that would have accompanied the army in the hope of economic gain along the way. Merchant shipping may have relied more on sail than rowers but the crew of another thousand vessels may well have added another one hundred thousand to the sea borne element alone. The army was clearly a large one and Herodotus gives a breakdown, taken presumably from a source that either remembered this occasion or drawn from knowledge of the various regions that came under Persian rule. The list of the various contingents may appear impressive (Herodt. 7.61–81) but simply illustrates the wide variety of armed troops that were available and could be levied by a Persian king. It says nothing about their military capability. Herodotus surely provides the list for the amazement of an audience who would not have seen such a sight, but he was also consciously emulating Homer’s catalogue in the Iliad of the participants in the protagonists of the Trojan War. Homer’s Trojan War was the portrayal of the supreme conflict, Herodotus’ war between the Greeks and the Persian Empire was meant to equal or even to surpass that ancient myth with one of his own time and perhaps crafting. The Persian army is therefore given a fabulous total number but it is worth remembering that at the final land battle at Plataea in the summer of 479 the invaders must have at least have equalled the Greek armed forces, which are said to have numbered one hundred thousand. The crossing of the Hellespont in the late spring of 480 and the end of the next summer casualties and the division of the army after Salamis between Xerxes and Mardonius must surely indicate armed forces somewhere in the region of two hundred thousand. Mardonius was left with the task of securing Greece by Xerxes so required sufficiently large numbers to overcome any opposition while the king could not be seen to return without a suitable bodyguard. Put the land forces total with the total from the fleet and merchant shipping and the number approaches half a million, not to mention camp followers, slaves and servants, plus all the pack animals and wagons and one can easily see why the total might be inflated further since such a force would blot out the landscape and appear almost like a swarm of locusts.

Because of the difficulties Mardonius had encountered in 492 and perhaps as a solution to the problem of sailing with Mount Athos first directly ahead and then to the right with strong tailwinds the decision was taken to bypass the peninsula altogether (Herodt. 7.24). The plan was to excavate a canal across the isthmus leading from the city of Acanthus to the peninsula on which Mount Athos is the dominating natural feature. As with his detailed description of the bridging of the Hellespont Herodotus is particularly precise about this as can be gauged from his narrative (Herodt. 7.22–24):

The Persians Bubares, the son of Megabazus, and Artachaees, the son of Artaeus, supervised the construction. For Athos is a great and famous mountain and comes down to the sea and is inhabited. At its furthest limit on the side of the mainland the mountain is a peninsula (‘chersonese’) and the isthmus at this point is twelve stadia.

The Persian engineers chose what may already have been an existing causeway and since the distance is less than two and half kilometres (about a mile and a half) and land mostly level, the construction ought not to have been that formidable. Yet Herodotus states (Herodt. 7.22) that work on the canal began three years before Xerxes’ army crossed the Hellespont. There was no shortage in the numbers of men available and many of these were drawn from the armed forces and transported to Athos by ship. The local communities were also obliged to provide labourers. Gangs of workers seem to have been collected along ethnic lines since the Phoenicians are said to have shown particular skill in the segment of the canal assigned to them. Finally, at the entrances to the canal breakwaters were built to prevent silting from the prevailing sea currents (Herodt. 7.37). Remains of the canal have been excavated but whether it was much more than the existing causeway with some water flowing through parts of it is questionable. Furthermore, the number of ships that passed this way when Xerxes had seen the canal is likely to have been a fraction of the ships in the fleet. Most captains would have taken the risk of sailing around the headland in mid-summer when the chance of gales was not as great as later in the year. It was, however, another instance of the overweening pride of the oriental despot, as Herodotus claims that the building of a canal was quite unnecessary (Herodt. 7.24) because ships could be easily dragged across the isthmus. Still, in the narrative it adds to the drama leading to the ultimate Persian failure and the humbling of Xerxes. The evidence suggests that the canal remained in use for a very short time, mainly because there was no city nearby to maintain the facility. It is surprising perhaps that the Athenians never showed the slightest interest in the canal when they were major importers of grain from the Euxine and when the shipping route from there to Attica was a very busy and lucrative one. This too possibly points to an unfinished or temporary project rather than one that was intended to last or that could easily have been utilized later.

The question of supply dumps in the campaign to Thermopylae is a very important issue and has seldom if at all been addressed by modern scholars. Herodotus places great emphasis on the incredible size of the Persian armament, both on land and on the sea; and, while some element of exaggeration is obvious in order to enhance the later victory of the Greeks, it is clear that the Persians came in force. But the campaign required intricate planning, which evidently took four years before the king even set foot in Europe and preceded the crossing of the Hellespont. Herodotus notes the placement of supplies along the march probably collected at the end of the summer in 481 since much of the material stored was perishable grain for making bread. Other supplies such as meat and fodder for the horses and other pack animals could be requisitioned from local towns and cities. Merchants accompanying the column sold all kinds of goods, and bought others, chiefly slaves. This enormous body of troops and camp followers is in modern parlance easily comparable to a moving hypermarket/superstore on foot! Xerxes was advised that there must be the placement of supplies along any route that initially lay through the Persian satrapy of Thrace and from there, via Macedonia whose king had made a treaty with the Persians, into Thessaly. The use of supply dumps seems an innovation, although Darius may have employed such measures on his march to the Danube in 513/12. Its use may be related to the fact that there were few wealthy cities along the route of advance through southern Thrace and the western border of Macedonia. Xerxes’ army and fleet marched or sailed from Cilicia, some of the ships or land forces from very much further afield, but there is no mention of the same exercise elsewhere because the route possessed sufficiently wealthy communities for requisition or market places. Herodotus names five places where supplies were brought by ship from Asia: Leuce Acte, Tyrodiza, described as ‘of the Perinthians’, Doriscus, Eion at the mouth of the River Strymon, and in Macedonia. Leuce Acte is said to have been chosen as the base for most of the equipment, raw materials or foodstuffs, which were transported by ship mostly from Asia Minor (Herodt. 7.25). Strabo in his geographical survey of the region lists the places along the western shore of the Hellespont from its southern entrance, and Leuce Acte is given as the fifth town after Aegospotami, which is two hundred and eighty stadia north of Sestos. The first and most important supply dump was therefore perhaps no more than four hundred stadia (80.8 kilometres, roughly 50 miles) distance from the Persian bridging point of the channel. If the intention had been to situate the supply depots along the route intended for the invasion force then Tyrodiza seems out of the way since Perinthus was situated towards the centre of the Propontis and lies six hundred and thirty stadia (127 kilometres or roughly seventy-five miles) from Byzantium and about twelve hundred stadia (250 kilometres or a little under 150 miles) from Eleus (Strabo, fr. 57). Ideally a supply depot should have been sited towards southern Thrace, but Herodotus’ text suggests that Tyrodiza was a harbour of Perinthus. Barker has made the attractive suggestion that Tyrodiza actually lay at the head of the Melian Gulf (Gulf of Saros) near or at the mouth of the Melas River. There is no evidence to support this conjecture but it is attractive in terms of the logistical placement of Persian supplies; and Xerxes’ army had to cross the Melas before moving into southern Thrace. Incidentally, Herodotus says (Herodt. 7.58) that the Melas River, like the Scamander River in the Troad (Herodt. 7.43), ran dry on account of the number of Persian troops and animals who camped there, which shows that it was one of the main halting points in this early part of the expedition. This point would also make tactical sense since it lies further along the direct route from Leuce Acte. No major urban centres are attested in this area, although Strabo (7.7.6) states that Greeks had settled there. Perinthus was a colony of Samos and therefore the Samians may also have been active at the Melas River. After the Gulf of Melas the next supply base is said to have been at Doriscus on the Hebrus River. Doriscus was clearly an ideal site since the beach and the surrounding country were flat (Herodt. 7.59). The fleet could be hauled ashore to dry off and there were sufficient land for an encampment of the entire army. That being the case, Herodotus claims that Xerxes insisted on carrying out a tally of his forces (Herodt. 7.60; cf. 7.87), which is said to have been one million and seven hundred thousand infantry and eighty thousand cavalry not to mention mounted camels and teams of chariots. The fleet consisted of three hundred warships from Phoenicia, two hundred from Egypt, one hundred and fifty from Cyprus, one hundred from Cilicia, thirty from the Pamphylians, fifty from Lycia, seventy from Caria, thirty from the Dorians living in Asia, one hundred from the Ionian Greeks, seventeen from the islands, and sixty from the cities of Aeolia; the cities of the Hellespont provided another one hundred but the citizens of Abydos were instructed not to accompany the fleet but were to guard the bridge (Herodt. 7.89). Besides this total figure, Herodotus states that there were another three thousand smaller vessels and transports. Diodorus (11.3.9 cf. Herodt. 7.184) claims that there were eighty hundred and fifty horse transports and about three thousand smaller vessels he names as triaconters or thirty-oared ships. Like Doriscus, Eion on the Strymon River, was in Persian hands and had been fortified by them since Darius had ordered Megabazus to occupy the region after the expedition against the Scythians (Herodt. 7.108). After Eion, Xerxes spent some time at Acanthus before moving on towards Macedonia where he ordered his fleet to await his arrival at Therme (Herodt. 7.121).

Compared with the difficulties encountered by Mardonius in 492 Xerxes’ advance across southern Thrace and into Macedonia went without any major mishaps. Still, between Acanthus and Therme, Herodotus notes (Herodt. 7.125–126) that lions attacked camels in the baggage train but not the usual pack animals. He is at a loss to explain their partiality but at the same time provides evidence for lions being common all the way between Abdera in southern Thrace to Acarnania in western Greece and almost to the northern shore of the Corinthian Gulf. The supply depot in Macedonia, and there may have been more than one, is not attested but is likely to have been at the coast rather than inland. The ruler of Macedonia at this time was Alexander I who had a treaty of friendship with the Persians and so was expected to provide help to Xerxes whose route lay through his kingdom. If the Persians sent supplies here in advance it may indicate that Macedonia was unable to provide for the numbers that were anticipated to gather there before moving south into Thessaly. Moreover, at this time the Macedonians had limited access to the sea since the best harbours in the region at Pydna and Methone were independent states. The fact that Xerxes was able to encamp his entire force at Therme (Herodt. 7.127) shows plainly enough that the final supply depot, although not initially specified, must have been at or near Therme. And the Persian forces occupied the coast from Therme all the way to the Haliacmon River, which marked the southern boundary of Macedonia at this time. The distance from Therme to the Haliacmon River was about fifty kilometres (30 miles) and must have been filled with the various camps of the contingents in the army and the ships of all sorts drying off in the summer heat.⁹⁰ The Persians evidently remained in Macedonia for a number of days if not weeks (Herodt. 7.131) for during this stay Xerxes went on ahead of his forces to explore the various possible routes by which he might enter Central Greece through the mountains, which mostly barred his way. Mount Olympus divides Macedonia from Thessaly and only one or two passable routes linked the two regions. The most feasible of these was the road, also the most obvious, which hugged the coast and ran between Mount Olympus and Mount Ossa – the gorge at Tempe – and seemed the logical course since the army and fleet needed to move in tandem. But there was another route about which Xerxes had been informed, which lay to the west of Olympus. Xerxes therefore sailed south to the mouth of the Pineus River to view his options. He was very surprised at the size of the river and when informed by local guides that all the rivers of Thessaly joined the Pineus before it entered the sea wondered if the river’s course might be diverted by some artificial means. When the king was told that Thessaly was surrounded on all sides by high mountains and that this was the sole possible exit a river might make to the sea he is said to have declared that by just damming the river at its gorge through the mountains before it reached the coastal plain the whole of Thessaly could easily be swamped. And Xerxes observed that the Thessalians had been clever to offer themselves as his allies and subjects knowing that their land was vulnerable to conquest such were his resources. The king’s curiosity was satisfied but not his plans for it must have been clear that another bridge or number of bridges would be needed at the mouth of the Pineas and that such construction would delay the invasion further. Apparently no longer interested in the coastal road into Thessaly Xerxes returned to Therme and gave orders that the inland route south was to be taken by his forces. This also meant that army and fleet would be separated for a number of days. Herodotus adds the rather odd information (Herodt. 7.131) that the forests, presumably to the west of Therme, were cut down by one third of Xerxes’ soldiers in preparation for their advance. It is far more likely that local timber was consumed in huge amounts by the fires needed in the various camps and for repairs to the ships. It is possible, although hardly credible, that wood might be carried for fording streams and rivers when the mountains through which they were about to depart were also forested unless Herodotus means that the forests were so dense that a road had to be cut through them. While the forest clearance was taking place heralds who had been despatched by Xerxes to the Greek communities further south demanding fire and water, the traditional signs of surrender, returned from their assignments, not all by any means successful (Herodt. 7.132). Still, among the Greeks to offer formal allegiance to the Persians were those who lived in Thessaly, Locri, Magnesia, Thebes and most of the cities of Boeotia, and Perrhaebia (through which the Persians were about to march on their way into Thessaly).

Herodotus’ account at this point appears to have been derived from more than a single source since having stated that the Thessalians submitted to Xerxes while the king was at Therme. Later in the narrative (7.173) as something of an apology Herodotus also claims that the Thessalians only deserted to the Persians when no alternative remained to them. This appears as if his source wished to exonerate Thessalian activities, although in the narrative it is explicitly stated that these Greeks served Xerxes well in the subsequent war. The Thessalians had earlier summoned help from the other Greek communities intent on fighting the Persians, and the response had been a combined force of Athenians and Spartans numbering about ten thousand hoplites. This force went by sea along the cost to Halus in Achaea Phthiotis and then crossed inland into Thessaly. Themistocles was in command of the Athenian troops, a Spartan named at Euaenetus of the Peloponnesian forces, and they took up a defensive position at the gorge at Tempe. The route through the gorge was narrow and overhung with high cliffs and even without opposition would have held up the Persian advance, although at that stage Xerxes had yet to cross the Hellespont. But the Greeks are said to have remained at Tempe only for a short time and retreated after they were advised by the Macedonian king Alexander that they would be vulnerable to an attack from the rear by another route from Macedonia and ran the risk of being caught on two fronts by the invaders. The Greek force marched south again and returned to their ships and the safety of Attica and the Peloponnese. What is not clear is just how long this force remained in Thessaly and must have withdrawn before Xerxes went to reconnoitre a way south for his army. Xerxes went in a Sidonian trireme, which Herodotus states was the ship and crew the king favoured (Herodt. 7.128). He was accompanied by a sizeable force, although probably not his entire fleet as Herodotus claims, and sailed to the mouth of the Pineus near Tempe. The date of Xerxes’ visit here is probably late June some weeks after the Greeks had departed and following the submission of the Thessalians. Xerxes does not appear to have remained at the Pineus for any length of time and returned to Therme before directing his army by the inland route into Thessaly. The Greeks may have missed an opportunity of intercepting the Persian king. But why would the Greeks have withdrawn in May when Xerxes had yet to march through Thrace unless Herodotus’ chronology is suspect and the defenders actually remained at Tempe until the Persians arrived at Therme? In May there was no need for a rapid withdrawal before the Persians were actually close at hand, unless it became known to Themistocles and his fellow commanders that the Thessalians were about to medize. There are missing details in Herodotus’ account and the chronology may require some alteration to make the Greek retreat and Thessalian desertion of the defence of Greece more causally related.