Luftwaffe Torpedo Bombers

Deployment of Convoy PQ18

Despite howls of Soviet protest, British strength was required elsewhere for Operation Pedestal within the Mediterranean. Following the catastrophe of PQ17, the Royal Navy was determined that PQ18 would not sail until much greater escort strength could be provided. It would be September before the convoy finally departed for Russia.

On 2 September PQ18 departed Loch Ewe, Scotland. Comprised of forty merchant ships (twenty American, eleven British, six Soviet and three Panamanian) a heavy escort was laid on which included an aircraft carrier for the first time: HMS Avenger carrying ten Hurricane fighters and three Swordfish torpedo bombers. A combined Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force task force of Hampden torpedo bombers, Catalina and Spitfire reconnaissance aircraft had also transferred to Vaenga airbase near Murmansk for potential operations against Tirpitz should she put to sea.

U-boat missions against PQ18 were planned, code-named Operation Eispalast. The outgoing QP14 was included, but deemed of secondary importance. Once again, large surface ships were readied for potential use against the convoy, although, as always, Hitler’s strict criteria would be used to determine their activation. They moved north to Altafjord on 10 September – Admiral Scheer narrowly missed by four torpedoes from HMS Tigris while in transit – and remained ready for sailing orders that never came. Hitler’s paranoia of losing his large ships rendered them once again useless.

Meanwhile PQ18 was detected briefly by Luftwaffe reconnaissance on 8 September. Oesten brought together a new U-boat group: Trägertod (Carrier killer). By 10 September U88, U403 and U405 were en route from the Spitsbergen and Bear Island area to a patrol line further west; U589, U377, U408 and U592 raced to join them. Additionally, U435 and U457 were scheduled operational by 12 September at Narvik, and U378 at Trondheim: and all would sail. U703 was refuelling at Harstadt, bringing the group number to eleven. Four others were earmarked for operations against QP14 following refuelling at Kirkenes: U255, U601, U456 and U251. At 1.20 p.m. on 12 September, Luftwaffe aircraft sighted PQ18 again, U405 making contact soon after and staying on station as beacon boat. The U-boats gathered, one of the next boats to begin shadowing was Kaptlt Bohmann’s U88; Bohmann was himself detected ahead of the convoy by HMS Faulknor of the ‘fighting escort’ – U88 accurately depth charged and sunk with all forty-six crewmen aboard.

The escorts and Avenger’s aircraft were kept busy attempting to force shadowing boats away from PQ18. However, at 9.52 a.m. on 13 September, Kaptlt Reinhard von Hymmen made the first torpedo hit on PQ18 when 3,559-ton Soviet steamer Stalingrad was sunk with one of three torpedoes, the ship going under in less than four minutes laden with ammunition, aircraft and tanks. Twenty-one of the eighty-seven crew were killed and the master, A. Sakharov, was last to leave the sinking ship, spending forty minutes in the water before being rescued and going on to act as pilot for the convoy. Von Hymmen had missed Stalingrad with two of his three torpedoes, but one had passed by the Soviet ship and hit 7,191-ton American Liberty Ship Oliver Ellsworth, the steamer executing a hard left turn to avoid the crippled Russian. The American ship was abandoned even before it had ceased moving, three of four lifeboats swamping and throwing their occupants into the water, though all except one US Navy armed guard were rescued. The wreck was finally sunk by shells from escorting ASW trawler HMT St Kenan.

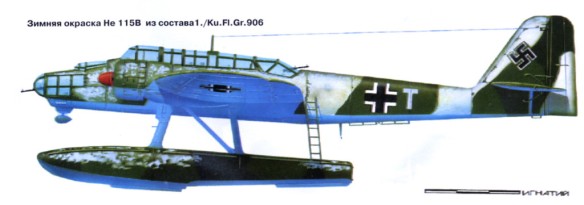

At almost the same time as Von Hymmen, Kaptlt Hans-Joachim Horrer fired two torpedoes toward HMS Avenger from U589 claiming to have scored at least one hit, although his shots missed. It may have been the detonations from U408’s attack that were heard through the freezing water aboard the submerged boat. That same day Horrer pulled four Luftwaffe airmen from their escape dinghy after their aircraft had been shot down during He111 torpedo bomber attacks that destroyed eight ships for the loss of the same number of aircraft. The airmen did not have long to enjoy their good fortune as the following day U589 was sighted by one of Avenger’s Swordfish. Though the biplane was chased away by a Luftwaffe Bv138 flying boat, the sighting brought destroyer HMS Onslow to the scene, catching U589 on the surface. Crash-diving, U589 was depth charged relentlessly by the destroyer until fuel oil, green vegetables and pieces of U-boat casing floated to the surface marking the grave of all forty-four crew and their four Luftwaffe passengers.

That same day there remained only one other confirmed sinking from PQ18. At 4 a.m., Brandenburg’s U457 hit 8,939-ton motor tanker Atheltemplar whose cargo of 9,400 tons of Admiralty fuel oil immediately began to burn. The crew abandoned ship south-west of Bear Island while minesweeper HMS Harrier attempted to scuttle the burning ship with gunfire, the attempt failing and the ship was left burning fiercely, later found by U408 after she had capsized – the hulk sent to the bottom with gunfire. Brandenburg claimed another 4,000-ton steamer sunk and two hits on a Javelin-class destroyer, but in this he was mistaken. Korvettenkapitän Rolf-Heinrich Hopman later claimed another destroyer hit on 16 September after a torpedo from U405 was heard to detonate after a run of over seven minutes. This too remains unsubstantiated, although the Allies definitely found Brandenburg’s U457 at 3 a.m. on that day. The U-boat was diving through the port bow escort screen when spotted: depth charges from HMS Impulsive destroying the boat along with all forty-five hands as oil, wreckage, paper and a black leather glove floated to the surface to mark the spot. The British illuminated the scene with a calcium flare before one further depth charge set to explode at 500ft was dropped to ensure the boat was sunk.

Elsewhere QP14 came under successful U-boat attack. Seventeen merchant ships, under heavy escort, were attacked by a total of seven U-boats that sank six ships. Strelow’s U435 sank minesweeper HMS Leda and three merchant ships: 5,345-ton American freighter Bellingham; 7,174-ton British steamer Ocean Voice; and 3,313-ton British freighter Grey Ranger during a single devastating assault on 22 September. Reche’s U255 sank 4,937-ton American PQ17 survivor Silver Sword while the destroyer HMS Somali was badly damaged by Kaptlt Bielfeld’s U703 and later sank in gale force winds while under tow.

PQ18 was judged a relative success by the Allies. Although thirteen ships in total had been lost, twenty-eight had arrived safely in the Soviet Union. Furthermore, three U-boats and forty Luftwaffe aircraft – including many skilled veterans of maritime operations – had been destroyed; the Luftwaffe were never again able to mount such strong attacks on the Russian convoys, as aircraft were gradually transferred south to the Mediterranean. The severe losses accrued by both PQ17 and PQ18 combined, coupled with demands elsewhere for Allied naval craft such as supporting Operation Torch, led to the suspension of the Arctic convoys until December 1942. Instead, independently sailing merchantmen would be despatched in what was known as Operation FB.

Between 29 October and 2 November, thirteen ships sailed at approximately twelve-hour intervals from Scotland to Murmansk. Although unescorted, there were ASW trawlers stationed at intervals along the route and local escorts available from Murmansk. From the ships that sailed, three were forced to abort their voyages and five were sunk, the remaining five reaching the Soviet Union. On 2 November ObltzS Dietrich von der Esch in U586 had already been at sea for three weeks, sailing in bad weather and suffering mechanical problems with the boat’s exhaust valves. An initial order to reconnoitre Jan Mayen was carried out before the U-boat sighted Operation FB ship Empire Gilbert and began a two-hour chase. The 6,640-ton steamer was missed by an initial double torpedo shot but hit on the port side by a second pair of torpedoes at 1.18 a.m.. The ship sank rapidly and when U586 reached the scene she was gone. The Germans pulled deck boy Ralph Urwin and gunner Arthur Hopkins aboard U586 from a floating beam, the pair barely able to move after submersion in the freezing water, and next attempted to question six survivors found aboard a raft but received no answer. Taking one more man, gunner Douglas Meadows, prisoner aboard the U-boat, U586 left the scene and later landed the three survivors at Skjomenfjord. The other sixty-four men were never seen again.

Two days later unescorted Liberty Ship William Clark was hit by a torpedo in the engine room from Kaptlt Karl-Heinz Herbschleb’s U354. A coup-de-grâce torpedo broke the ship in two and sent her to the bottom, 31 of the 71 crew either killed in the sinking or lost at sea as their lifeboats drifted away.

The final ‘FB’ ships sunk by U-boat were both destroyed by ObltzS Hans Benker’s U625 engaged upon its maiden war patrol. The 5,445-ton British steamer Chulmleigh had been bombed by Ju88 aircraft and beached on Spitsbergen’s South Cape when Benker torpedoed the stranded wreck and finished it off with gunfire on 6 November. That night he sighted 7,455-ton British Empire Sky and hit her with two torpedoes. As the steamer settled into the water a coup de grâce ignited its ammunition cargo and she exploded, flinging debris over a wide area, one piece weighing a kilogram clattering down the conning tower hatch into the U-boat’s control room. All sixty men aboard the shattered freighter were lost.

PQ18 – The First Air Support for the Convoys

PQ17’s fate could not be ignored. It was necessary to maintain the link between the Western Allies and the beleaguered Soviet Union. Four British destroyers were despatched to Archangel loaded with ammunition and replacement anti-aircraft gun barrels, as well as interpreters in an attempt to improve liaison with the Russians. The ships arrived on 24 July 1942. On 13 August the American cruiser USS Tuscaloosa sailed for Russia, escorted by a British destroyer and two American destroyers, carrying RAF ground crew and equipment as well as aircraft spares for two squadrons of Handley Page Hampden bombers destined to be based in northern Russia, as would be photo-reconnaissance Supermarine Spitfires and a squadron of RAF Coastal Command Consolidated Catalina flying boats. Also included in the cargo carried by these warships was a demountable medical centre with medical supplies, but while the Soviets took the medical supplies, they rejected the hospital that would have done so much to improve the lot of Allied seamen in need of medical attention on reaching a Russian port.

Survivors from PQ17 were brought home to the UK aboard the three American ships plus three British destroyers. Ultra intelligence led the three British destroyers to Bear Island where they discovered the German minelayer Ulm, and while two of the destroyers shelled the ship, the third, Onslaught, fired three torpedoes with the third penetrating the magazine, which exploded. Despite the massive explosion, the commanding officer and fifty-nine of the ship’s company survived to be taken prisoner.

Less successful were the Hampden bombers. Already obsolescent, several were shot down on their way to Russia by the Germans and, perhaps due to mistaken identity, by the Russians, who may have confused the aircraft with the Dornier Do 17. Unfortunately, one of those shot down by the Germans crashed in Norway and contained details of the defence of the next pair of convoys, PQ18 and the returning QP14. QP14 was to be the target for the Admiral Scheer, together with the cruisers Admiral Hipper and Köln and a supporting screen of destroyers. This surface force moved to the Altenfjord on 1 September.

PQ18 was the first Arctic convoy to have an escort carrier, the American-built Avenger. The ship had three radar-equipped Swordfish from No. 825 NAS for anti-submarine duties, as well as six Hawker Sea Hurricanes, with another six dismantled and stowed beneath the hangar deck in a hold, for fighter defence. These aircraft were drawn from 802 and 883 Squadrons. Another Sea Hurricane was aboard the CAM ship Empire Morn. Other ships in the convoy escort included the cruiser Scylla, 2 destroyers, 2 anti-aircraft ships converted from merchant vessels, 4 corvettes, 4 anti-submarine trawlers, 3 minesweepers and 2 submarines. There was a rescue ship so that the warships did not have to risk stopping to pick up survivors, and three minesweepers being delivered to the Soviet Union also took on this role.

The convoy had gained an escort carrier but the Home Fleet, which usually provided the distant escort – a much heavier force than that providing the close escort – had lost its fast armoured fleet carrier, Victorious , damaged while escorting the convoy Operation PEDESTAL to Malta and being refitted as a result. Also missing were the American ships, transferred to the Pacific. The C-in-C, Home Fleet, Admiral Sir John Tovey, also made other changes. This time he would remain aboard his flagship, the battleship King George V , at Scapa Flow where he would have constant telephone communication with the Admiralty, while his deputy, Vice Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, went to sea in the battleship Anson . Both PQ18 and QP14 had a strong destroyer escort with the freedom of action to leave the close escort to the corvettes, armed trawlers, AA ships and minesweepers if the situation warranted it. To save fuel, the officer in command of the destroyers, Rear Admiral Robert Burnett aboard the light cruiser Scylla, ordered that no U-boat hunt was to exceed ninety minutes.

In addition, the convoy would have the support of Force Q and Force P, both comprising two fleet oilers, or tankers, and escorting destroyers, which were deployed ahead of the convoy to Spitzbergen, Norwegian territory not taken by the Germans but that had Russians ashore working on a mining concession dating from Tsarist times. A re-supply operation for the garrison in Spitzbergen was linked with Force P and Force Q.

Iceland was the main rendezvous, but getting there was difficult despite it being summer. Seas were so rough that a Sea Hurricane was swept off Avenger ’s deck, and the steel ropes securing aircraft in the hangars failed to stop them breaking loose and crashing into one another or the sides of the hangar. Fused 500lb bombs stored in the hangar lift-well broke loose and had to be captured by laying down duffel coats with rope ties, which were secured as soon as a bomb rolled onto one of the coats. Fuel contamination with sea water meant that the carrier suffered engine problems. It also seems that remote Iceland was not remote enough, or safe enough, for the carrier was discovered and bombed by a Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor long-range maritime-reconnaissance aircraft that dropped a stick of bombs close to Avenger but without causing any damage.

The engine problems meant that the convoy, already spotted by a U-boat while en passage to Iceland from Scotland, had to sail without the carrier and, on 8 September, the convoy was discovered by another Condor. Low cloud then protected the convoy from German aircraft until 12 September when a Blohm und Voss BV 138 flying boat dropped through the clouds. By this time, Avenger had caught up with the convoy and was able to launch a flight of four Sea Hurricanes, but not in time to catch the German aircraft before it disappeared.

Swordfish were extremely vulnerable on the Arctic convoys which, unlike those across the Atlantic, also had to face German fighters. As a result, the fighters from Avenger not only had to protect the ships in the convoy from aerial attack, they had to protect the Swordfish as well. At 0400 on 9 September, the Sea Hurricanes were scrambled after Swordfish on anti-submarine patrols were discovered by a BV 138 flying boat and a Junkers Ju 88 reconnaissance aircraft, but both disappeared into the clouds before the Hurricanes could catch them. Another Swordfish patrol discovered that the BV 138s were laying mines ahead of the convoy.

PQ18 was repeatedly attacked from the air, which meant that the ships had to make mass turns and put up heavy anti-aircraft fire, all of which made life for the returning Swordfish crews very interesting as aircraft recognition was not as good as it could be and the single-engined biplane Swordfish were often mistaken for twin-engined monoplane Ju 88s. Ditching in the sea was never something to be considered lightly but in Arctic waters, even in summer, survival time could be very short indeed.

The Sea Hurricanes attempted to keep a constant air patrol over the convoy with each aircraft spending twenty-five minutes in the air before landing to refuel, but with just six operational aircraft, keeping a constant watch over the Swordfish as well as the convoy was impossible.

On 14 September, the first Swordfish of the day found U-589 on the surface, but she dived leaving the Swordfish to mark the spot with a smoke flare. Once the aircraft had gone, the submarine surfaced and continued charging her batteries, but alerted by the Swordfish the destroyer Onslow raced to the scene. Once again U-589 dived, but the destroyer attacked with depth-charges and destroyed her. As a result the Germans, so far not accustomed to a convoy having its own air cover and aerial reconnaissance, were forced to change their tactics. Reconnaissance BV 138s and Ju 88s were sent to intimidate the Swordfish, forcing them back over the convoy until the Germans were so close to the ships that they were driven off by AA fire. The Swordfish would then venture out, only to be driven back again.

Later that day, another attack by Ju 88s was detected by the duty Swordfish. This time, Avenger herself was the target. Her maximum speed was just 17 knots, much slower than an ordinary aircraft carrier, but fortunately the Sea Hurricanes broke up the attack and no ships from the convoy were lost, while most of the eleven Ju 88s shot down had succumbed to anti-aircraft fire. Further attacks followed that day, again without any losses to the convoy, although another German aircraft was shot down. In a final attack, three of the four patrolling Hurricanes were shot down by friendly fire from the convoy’s ships but all three pilots were saved. In this last attack of the day, Avenger ’s commanding officer Commander Colthurst successfully combed torpedoes dropped by the Germans. A bomb dropped by a Ju 88 pilot, who flew exceptionally low to make sure he did not miss the target, hit the ammunition ship Mary Luckenbach, which blew up, taking her attacker with her. The sole survivor from the ship was a steward who had been taking the master a cup of coffee, was blown off the upper deck by the explosion and found himself in the sea half a mile down the convoy.

Not all rescues were left to the rescue ships. At the height of the battle for PQ18, the destroyer Offa saw a cargo ship, the Macbeth, hit by two torpedoes and beginning to sink with her cargo of tanks and other war matériel. Offa ’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Alastair Ewing, took his ship alongside Macbeth and, at the cost of some guard rails and stanchions, took off all her ship’s company before she sank. One Sea Hurricane pilot had been very lucky to be snatched out of the sea within minutes of baling out by the destroyer Wheatland which was acting as close escort for Avenger , her role also being what became known as a ‘plane guard’, fishing unfortunate naval aviators out of the sea.

The next day, the remaining Sea Hurricanes and the Swordfish were again in the air, with the former breaking up further attacks. It was not until 16 September that the Swordfish were relieved of their patrolling by shore-based RAF Consolidated Catalina flying boats of No. 210 Squadron operating from Russia. However, the break was short-lived. Later that day the convoy passed the homeward convoy QP14 with the survivors of the ill-fated PQ17 and Avenger, with her aircraft and some of the other escorts transferred to this convoy. The interval had been used by the ship’s air engineering team to assemble five Sea Hurricanes, more than replacing the four lost on the outward voyage. In all, the Sea Hurricanes had accounted for a total of 5 enemy aircraft and damaged 17 others out of a total of 44 shot down. It was fortunate that the three Fairey Swordfish remained serviceable as no replacement aircraft were carried.

During the convoy, Avenger ’s commanding officer had changed the operational pattern for the Sea Hurricanes in order to get the maximum benefit from his small force, having a single aircraft in the air most of the time rather than having all of his aircraft, or none of them, airborne at once.

Once the Sea Hurricane flight had been so depleted, it fell to the CAM ship Empire Morn to launch her Hurricane, flown by Flying Officer Burr of the RAF. The launch was accompanied by friendly fire from other ships in the convoy until he was finally out of range. Despite problems with the barrage balloons flown by some of the merchantmen, he managed to break up a German attack, setting one aircraft on fire. Once out of ammunition, he saved his precious aircraft by flying it to Keg Ostrov airfield near Archangel. As previously mentioned, this ‘one-off’ use of aircraft from the CAM ships was a major drawback as convoy commanders were reluctant to use them in case a more desperate situation emerged later in the convoy’s passage. Cases of CAM ship fighters being saved were very rare.

Clearly, even an escort carrier with a mix of fighters and anti-submarine aircraft was hard-pressed to provide adequate air cover. It is hard to escape the conclusion that two escort carriers would have been needed, or a larger ship such as Nairana or Vindex with up to fourteen Swordfish and six Wildcat fighters, a much better aircraft than the Sea Hurricane. Again, even with these two ships one might suggest that the balance between fighters and anti-submarine aircraft was wrong for an Arctic convoy.

Inevitably, as the convoy approached its destination there was no sign of the promised Red Air Force air cover. This was typical of the experiences of those on the convoys to Russia, with neither Russia’s air forces nor her navy providing any support. Indeed, apart from some coastal bombardment as the Red armies swept westwards, the main achievement of the Russian navy was for its submarines to sink the merchantmen carrying German refugees away from the Russians and one of these attacks resulted in the greatest recorded loss of life at sea as the Germans struggled to evacuate more than 1.5 million civilians.

There were many more convoys to Russia still to come at this stage, but PQ17 and PQ18 were two of the most famous. The convoys were a demanding operation for both the Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy, one that Stalin never recognized and there was no Soviet contribution to the escorts. The convoys continued, despite German attacks and the weather, until the war’s end, with the exception of the period immediately before, during and after the Normandy landings when a massive effort was required that demanded the escorts and especially the larger ships. That finally gave Stalin the only battlefront that he would recognize as being a ‘second front’.