Henry’s court in November reflected his heightened status on the European stage, as it was visited by envoys from the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Comnenus, from the Holy Roman Emperor, and from the count of Flanders. Such was Henry’s renown that the king of Sicily, William II, sought an alliance by marrying Henry’s daughter Joan in February 1177. Perhaps even more importantly, Henry’s new model of ‘a family firm’, with regular conferences, continued to pay dividends in Aquitaine, where Richard’s permanent presence, rather than rule by an absentee lord such as Henry, finally allowed the pursuit of full ducal authority. However, suppressing rebellion was one thing; bringing traditionally autonomous counties such as Angoulême under control was another. Early signs of Richard’s military skill, tenacity and tactical awareness can be seen in the way he dismantled the strongholds that supported the count of Angoulême by the end of May 1179, including the château de Taillebourg where he had sheltered from his father’s wrath in 1173. The contrast this time could not be greater; after reducing the great castle to rubble, having played a leading role during hand-to-hand combat to wrest control of the gatehouse to gain entry, Richard journeyed to England where he was ‘received by his father with the greatest honour’ and confirmed as ruler of Aquitaine. Thus was born Richard’s reputation as a fearless leader, a warrior with the heart of a lion who was happy to throw himself into the fray alongside his men. As well as a lifelong fascination with the arts of siegecraft and castle-building, he was always looking for opportunities to test his ingenuity against ever more challenging fortresses.

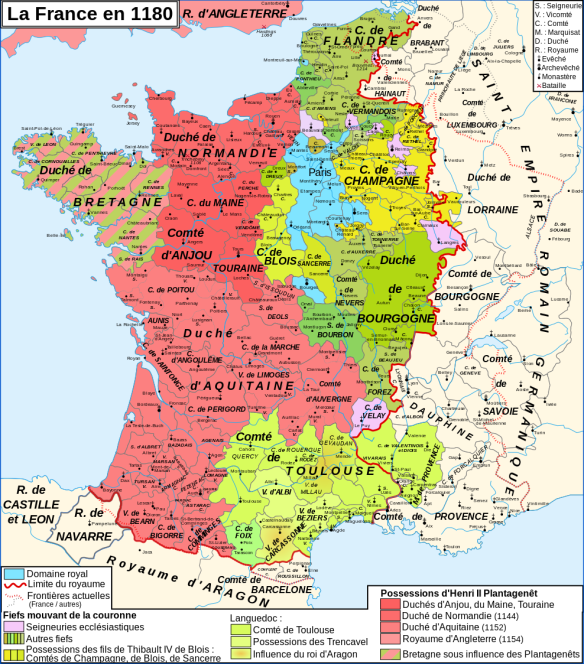

Henry had not forgotten the role played by Louis in stirring up trouble amongst his family, and decided that the time was right to go back onto the offensive, focusing on the contentious areas of Berry and Auvergne – important to Louis as the principal communication route to the southern portion of his realm, yet vital to secure the borders of Aquitaine. In 1177, Henry demanded the handover of Margaret’s dowry – the Norman Vexin – plus lands in Berry for Alice’s dowry as part of her marriage to Richard, and backed up his demands by mustering an army. The sabre-rattling worked. Against the background of increasing tension in the Holy Land, and calls for another crusade to provide assistance to the beleaguered Western strongholds which were under assault from Saladin, Louis and Henry signed a non-aggression pact at Ivry in September 1177 on the basis that they would prepare for a joint military expedition to the Holy Land. Furthermore, the spirit of the agreement was of mutual cooperation – ‘We are now and intend henceforth to be friends, and that each of us will to the best of his ability defend the other in life and limb and in worldly honour against all men,’ removing all claims from each other’s lands. Yet Henry was able to manipulate the situation to his advantage, ensuring the status of Berry, Auvergne and Châteauroux was decided by arbitration at Gracay in November. Not only was the verdict in Henry’s favour, but he also persuaded the lord of La Marche to sell him his lands, which hemmed in the troublesome Aquitainian lords in Poitou, Angoulême and Limoges and acted as a ‘marcher’ state with Berry and Auvergne.

Although this was a major threat to French influence in the south, Louis was no longer in a position to act. He was old and worn out from his struggles with Henry; his focus was to ensure that his only son, Philip, would follow him as king. Louis planned to have Philip crowned as his successor when he turned fourteen on 15 August 1179, but Philip fell so seriously ill that it was feared he would die. Postponing the coronation, Louis travelled to England on 22 August, directed to the shrine of St Thomas at Canterbury in a dream. Henry received his fellow king with courtesy, escorting him to the cathedral where Louis prayed for two days. Philip duly recovered and was crowned on 1 November at Reims, with the Angevins represented by young Henry, Richard and Geoffrey; Louis, however, missed the ceremony – he had suffered a stroke on the return journey from Canterbury and was left paralysed, unable to speak: ‘a spectator in the last years of his reign’. He finally died on 18 September 1180 leaving his son at the mercy of court politics. Thereafter followed a power struggle for influence over the new king, with Louis’s widow Adela and her brothers, the counts of Blois, Chartres, Champagne and Sancerre, ranged against the count of Flanders, who had previously arranged for Philip to marry his niece, Isabella of Hainault, in April 1180. Philip sided with his bride’s family, and Adela fled from court; in a twist of fate, the Blois faction appealed to Henry to intervene and facilitate a reconciliation.

When Philip subsequently turned against the count of Flanders in a dispute over control of the Vermandois, Henry was again called in to resolve the conflict as the ‘elder statesman’ of Europe. Prior to his departure to the conference, on 22 February 1182 he dictated his last testament as a precaution, sending a copy to the royal treasury at Westminster and another to Canterbury cathedral for safety. Once in France, he presided over the reconciliation process, surrounded by his former enemies; also present with the king of France and count of Flanders was Henry, the young king, and William, king of Scotland. Chroniclers were moved to write that, ‘We have read of four kings falling together in the same battle, but seldom have we heard of four kings coming peacefully together to confer, and in peace departing.’ Unfortunately, it was to be the last peace Henry was to know.

#

Despite all his efforts, Henry’s land-share model for federal government fell apart during the next seven years. It is easy to blame the ageing king for failing to relinquish his grasp on power, but this argument does not hold water. In 1181 he had passed Brittany over to Geoffrey to govern in person, and permitted Richard a free hand to tackle the Aquitainian lords. However, Richard’s hand was too heavy, and soon loud complaints could be heard emanating from the deep south as his tactic of imposing long-dormant ducal rights on traditionally independent lords was criticised amid accusations that he ‘oppressed his subjects with burdensome and unwanted exactions and by an impetuous despotism’.

The problem was that the legend of Eleanor’s court of love epitomised the romantic ideal of the emerging code of chivalry, but there was a darker side that required knights to prove their mettle in battle, especially ‘free lances’ that were not attached to the household of a particular lord and could therefore ill-afford to take part in the many tournaments that were held around the counties of France and across the Holy Roman Empire. Troubadours such as Bertran de Born earned their living composing songs of knightly heroic deeds, but during times of peace he sang to a different tune. In a deliberate attempt to cause discontent, Bertran would write political songs inciting violence or mocking the various lords in the hope of stirring up local conflict between them – a medieval version of preachers of hate: ‘I would that the great men should always be quarrelling among themselves.’ Richard brought peace, and it was not to the liking of Bertran and his comrades. Yet trouble was always just around the corner. After the death of Vulgrin, count of Angoulême, in 1181, Richard attempted to impose northern principles of feudal jurisdiction, and claimed that Vulgrin’s infant daughter should be the heiress (and therefore the duke of Aquitaine’s ward), when according to southern custom the county should have passed to one of Vulgrin’s two brothers. Despite the exhortations of Bertran, who had spotted a chance to make mischief and stir up trouble amongst the local barons, the ensuing uprising was somewhat half-hearted; nevertheless, the noise of further unrest coming from Aquitaine forced Henry to intervene. He called the leading lords to a conference at Grandmont in the spring of 1182, shortly after his diplomatic mission to France, and, when the results were inconclusive, helped Richard crush the rebellion via a campaign in the Limousin.

This intervention by Henry in Aquitainian politics was an exception rather than the norm and, although he was concerned by some of Richard’s methods, Henry was happy to let him continue as ruler. The real cause of the old king’s problems was his oldest son, who – unlike Richard and Geoffrey – showed no interest or aptitude for government, yet resented the fact that he held no territory of his own, failing to recognise that hard work, diplomacy and administrative skills were required to wield power. Young Henry had left England in 1176 and headed straight for the glamour of the tournament circuit across France, where he built up a reputation as a dashing, handsome and generous knight who was immensely popular and charming. Young Henry had been assigned to the care of William Marshal, who mentored him in the code of chivalry: ‘When in arms and engaged in war, no sooner was the helmet on his head than he assumed a lofty air, and became impetuous, bold, and fiercer than any wild beast.’ However, it is likely that the siren calls of the troubadours encouraged him to spend money profligately on lavish feasts and in supporting his retinue of young knights, leaving him impoverished, dependent on his father for funds, yet resentful that he could not enjoy the revenues of the lands that he saw as rightfully his. Young Henry struck up a close friendship with the count of Flanders in the late 1170s, and became equally attached to his brother-in-law Philip of France in the early 1180s.

In 1182, Henry had summoned his oldest son to join the campaign in the Limousin at the siege of Perigord, reinforcing the concept that the family pulled together during a time of trouble; but – as always – young Henry dallied along the way and arrived late. Towards the end of the summer, the young king demanded ‘that he be given Normandy or some other territory, where he and his wife might dwell, and from which he might be able to support knights in his service’. The request was rejected out of hand as impertinent, and young Henry stormed off in disgust to the court of his brother-in-law, Philip. This was exactly the same pattern of behaviour that had led to the war in 1173, and Henry was sufficiently alarmed to relent partially. A string of messengers sent to Paris carried offers of money – 100 livres Angevin (around £25 sterling) per day for young Henry, and 10 livres Angevin for his wife. This overly generous offer seemed to do the trick, with the message sent back that young Henry ‘would not depart from his [father’s] will and counsel, nor demand more from him’. These proved to be hollow words, and the real reason for his strange behaviour during the summer became apparent when the family assembled for Henry’s Christmas court at Caen in Normandy. The peace was disturbed when William Marshal burst into the ducal residence, demanding to be heard. Shaking with anger, he formally requested that he be permitted to challenge the young king in trial by combat as a way of proving his innocence in relation to certain scandalous allegations brought against him – namely, that he had conducted an inappropriate affair with young Henry’s wife, Margaret. This was a serious charge, and almost certainly untrue; although Marshal’s request was denied and he was banished from court in disgrace, the incident deeply unsettled Henry and raised suspicions about what was really going on within the young king’s household.

The family had been discussing matters of great importance. Marshal’s interruption and subsequent banishment had clearly added to the tension of the debate. Instead of heading their separate ways, the sons accompanied Henry to his next destination at Le Mans in January 1183. It was here that a huge argument erupted between young Henry and Richard, ‘for whom [Henry] had a consuming hatred’. At the heart of the matter was the young king’s confession that, ‘He had pledged himself to the barons of Aquitaine against his brother Richard, being induced to do so because brother had fortified the castle of Clairvaux, which was part of the patrimony promised to himself, against his wishes.’ As to who had put such thoughts in his head, it is interesting that Bertran de Born – the notorious troublemaking troubadour – had written,

… between Poitiers and l’Île Bouchard and Mirebeau and Loudun and Chinon, someone has dared to build a fair castle at Clairvaux, in the midst of the plain. I should not wish the Young King to know about it or see it, for he would not find it to his liking; but I fear, so white is the stone, that he cannot fail to see it from Matheflon.

Equally, young Henry might have been encouraged by King Philip, a fast learner about the benefits of sowing discord amongst one’s enemies – truly his father Louis’s son.

Richard was furious; technically, Clairvaux had been under the control of Anjou, but was situated at the very northern tip of Poitou and therefore claimed by his jurisdiction. Furthermore, the confession that young Henry had been actively undermining Richard was tantamount to admitting that he was planning a coup; no wonder young Henry had dragged his feet when summoned to join in the family assault on the Aquitanian barons, with whom he was probably in cahoots or at least sounding out the opportunity for an alliance. Given young Henry’s characteristics, he represented a much more palatable proposition to the locals than his iron-willed brother. Henry senior tried to defuse the situation and persuaded Richard to hand Clairvaux over to young Henry, whilst summoning the discontented Aquitainian barons – mainly the Taillefer and Lusignan families – to meet him and his sons at Mirebeau; Geoffrey was entrusted to deliver the message in person.

As the court moved on to Angers, Henry tried once again to resolve matters. However, in trying to provide some clarity over his plans for the division of territories, the king made a terrible blunder. His insistence that they all swore obedience to him and perpetual peace to one another, as well as acknowledge that his decision to divide the territories, along the lines agreed in 1169, was acceptable; his insistence that Richard and Geoffrey swear oaths of allegiance to young Henry as the future head of the family commonwealth provoked a furious response. Richard angrily refused to comply, on the grounds that they were brothers of equal birth status. As his father grew more exasperated, Richard grudgingly relented – only for the young Henry to refuse unless the oaths were sworn on the Gospels. This enraged Richard still further, and he argued that he held Aquitaine from his mother, not his father, directly from the king of France, so there were no grounds on which he should perform homage to his brother. Having made his feelings clear, Richard stormed out of the conference ‘leaving nothing behind him but altercations and threats’ and ‘returned in haste to his own territory and fortified his castles and towns’.

Henry was ‘incandescent from the heat of anger’ but, after he had calmed down, the young king approached him and offered to follow his brother to Aquitaine and broker a peace between Richard and the barons. Despite a natural wariness of his eldest son’s intentions, the old king was pleased that he was taking the situation seriously and wanted to salvage the succession plans. On these grounds, Henry gave permission for him to travel south. However, this proved to be another catastrophic mistake; the young king immediately sent his wife to Paris for safe keeping, as his intention all along had been to follow up on his conversations with the Aquitainian barons and go to war against Richard. As soon as he crossed the border from Anjou, the young king ‘secretly accepted security from the counts and barons that they would faithfully serve him as their lord and would not depart from his service’, and prepared to evict Richard from Aquitaine so that he could claim it for his own.

Henry found out about his son’s betrayal in February 1183; he had followed the young king into Limoges with a small escort, ostensibly to lend support should it be required. Instead he was stunned to find young Henry inside the city conversing happily with the rebel leaders – and even more shocked when the residents opened fire on him with arrows, one of which ripped through his cloak. Negotiations between the two sides lasted several days, even though Henry did not have enough men to besiege the city, despite the city’s defences still being in a state of disrepair after Richard’s previous assault. Yet Henry was even more dumbfounded when a large contingent of Breton mercenaries arrived on the scene, led by Geoffrey – not to help him, but to lend support to the young king’s attempted coup.

This was a bitter blow, but completely in character; Geoffrey was said to be ‘overflowing with words, smooth as oil, possessed by his syrupy and persuasive eloquence, able to corrupt two kingdoms with his tongue, of tireless endeavour and a hypocrite in everything’. It’s likely that Geoffrey had arranged the finer details for the coup when he left court at Le Mans to summon the barons to Mirebeau. Worse still, King Philip – who had grown particularly close to his brother-in-law – saw an opportunity to cause trouble and, declaring an interest in southern affairs as the overlord of both Henry and Richard, moved into the region with armed forces. Other local powers waded into the fray, including the count of Toulouse and the duke of Burgundy. By the spring, Aquitaine was seriously destabilised by the crisis and slid towards anarchy as the various factions struggled for supremacy. For Henry, the similarity with 1173 must have been striking, but things were a little different this time. For a start, not all his sons were ranged against him and Richard was a formidable ally, able to call upon mercenaries of his own to confront the rebels. With restless energy typical of his family, Richard moved across Poitou, routing the Breton forces that had invaded, butchering or mutilating them without mercy. Limoges was besieged, and rebel castles attacked.

Suspecting his position had become hopeless, young Henry slipped out of Limoges to join his allies in Angoulême, before moving further south in May without any clear strategy. Indeed, he was so short of cash to pay his troops that he resorted to raiding monastic houses and shrines including Rocamadour, one of the most famous in Europe. Around 25 May, he contracted dysentery and slowly made his way back towards Limoges. By 7 June he had reached Martel, but it was clear to his followers that he was dying. Young Henry made his confession and received the last rites, and asked that his father meet him one final time: ‘He was smitten with remorse and sent to his father that he would condescend to visit his dying son.’ However his duplicity earlier in the year meant that Henry was highly suspicious; the king’s advisors were wary of a trick, and he did not go. Instead, Henry did send a ring ‘as a token of mercy and forgiveness and a pledge of his paternal affection’. However, it was too late: ‘On receiving the ring the son kissed it and immediately expired,’ on 11 June. The news of his death was broken to Henry as he sheltered from the hot sun in a humble peasant’s cottage, whilst still besieging Limoges. The king was stricken with grief: ‘He cost me much, but I wish he had lived to cost me more.’ Nevertheless, business came first. Limoges surrendered on 24 June, Geoffrey fled back to Brittany and Philip – no longer able to claim he was supporting his brother-in-law – withdrew, as did the count of Toulouse and duke of Burgundy. Richard and Henry mopped up the opposition; Bertran de Born’s castle at Hautefort was among the castles that were seized, probably to the great satisfaction of all who had been on the receiving end of his pithy songs.

The young king’s funeral took place at Rouen on 3 July 1183, after which Henry met with his remaining sons at Angers to reconsider his plans for governing the family lands. There is evidence that he was softening his tone towards his captive wife at this time as well, allowing Eleanor to undertake a tour of her dower lands in England, which she gratefully seized. It was a shrewd move to bring her back into the family circle, as it was not long before his sons were quarrelling again; the more Henry tried to clarify his intentions, the more upset he caused. In September, he unveiled a new model for the division of lands – Richard was to hand Aquitaine to John, and take up the role that young Henry had performed as heir to England, Normandy and Anjou. Unsurprisingly, given his upbringing in the south and the amount of hard graft he had put into the subjugation of Aquitaine, Richard refused – especially as there were grave concerns about John’s youthful lack of experience, which was probably the last thing that was required after the turbulence of the last two years. Once more, Richard departed a family conference in anger and headed south.

One can almost hear Henry gnashing his teeth in frustration at the unwillingness of Richard to cooperate; he had misunderstood the passion that his son felt for the land he’d come to think of as home. Despite all the heartache that military intervention had caused, Henry’s initial reaction was to challenge John to raise an army and take Aquitaine by force, but Henry’s youngest son had no source of revenue and it would appear to have been a half-hearted gesture made in anger. By August 1184 the king was back in England, but no sooner had he left the continent than Geoffrey was stirring up trouble once more, persuading John to raise an army to invade Poitou – although in reality the campaign amounted to little more than border raids in which they ‘burned towns and carried off booty’, provoking Richard to retaliate and strike back against Brittany. Henry did what any exasperated parent would do and summoned all his children to England for a dressing-down; they stayed with him until the end of 1184, and in December the king ‘made peace between his sons’.

It is very easy to focus on a decade of family squabbles, in the way that the Becket affair tends to dominate the manner in which Henry’s earlier reign has been depicted. The old king’s failure adequately to resolve his succession should not mask the fact that he was still held in high regard internationally, evidenced by the willingness of former enemies to turn to him for mediation. Perhaps the most powerful indication of Henry II’s standing at this time as Europe’s elder statesman came in 1185, when the patriarch of Jerusalem visited the royal court at Reading on 29 January and, with theatrical gravitas, approached the king and placed the banner of the kingdom of Jerusalem, complete with the keys to the city, the keys to the tower of David and the keys to the Holy Sepulchre at his feet. He then formally offered the throne to Henry.

For some, this would have been the greatest honour imaginable, and certainly represented a remarkable turnaround in the relationship between Henry and the church from the dark days of 1170. However, this was a poisoned chalice; as Henry was to remark to Gerald of Wales, ‘If the patriarch or anyone else comes to us, it is because they are seeking their own advantage.’ The situation in the Holy Land was grim. The remarkable rise of Saladin as the leader of the Fatimid government in Egypt, and his subsequent conquest of Syria and much of the surrounding territory, now posed a direct threat to the remaining Crusader states, in particular the kingdom of Jerusalem. Its leader was the ailing Baldwin IV, Henry’s cousin – they shared the same grandfather, Fulk V of Anjou, who had settled the county of Anjou on his son Geoffrey so he could marry the kingdom’s heiress, Melisende, on 2 June 1129. Baldwin was aware of the military threat to his borders and was looking for a warrior to succeed him; the offer to Henry was a way of continuing the family connection.

However, with the succession of his own lands clearly unsettled, Henry was reluctant to follow the example of his grandfather and abdicate – although in hindsight this might have been the perfect opportunity for him to exit centre stage with his reputation largely undamaged. Instead, the king summoned a council in March to discuss the issue in a suitable setting in Clerkenwell, inside the church of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem. All leading vassals were invited, including William of Scotland and his brother David – making the point that they were considered tenants-in-chief of the king. The advice that Henry was given in relation to Jerusalem sounds very familiar to a modern audience:

It seemed better to all of them, and much for the safety of the king’s soul, that he should govern his kingdom with due care and protect it from the intrusion of foreigners and from external enemies, than that he should in his own person seek the preservation of Easterners.

To Henry’s mind, the uncertainty around the succession and the violent squabbles of his children made it impossible for him to leave. Nor was it possible to extend the offer to one of his children, despite the desperate enthusiasm of his youngest son John who – on bended knee – begged permission to go; Henry had other plans, and dispatched him to Ireland to claim the lordship that had been given him in 1177. However, the campaign was a disaster. John was accompanied by a coterie of young knights who offended the local chiefs, sidelined the Anglo-Norman planter families, spent all the campaign funds on revelry, and united everyone against him. Meanwhile, Henry agreed to confer with Philip of France about aid for Jerusalem, perhaps a tacit recognition of French primacy in the Holy Land: Fulk V had sought permission from his overlord, Louis VI, before accepting the offer of marriage to Melisende and abdicating Anjou. The two kings agreed to offer money to help support an army, but this was not what the patriarch wanted: ‘Almost all the world will offer us money, but it is a prince we need; we would prefer a leader even without money, to money without a leader.’ Instead, Jerusalem passed to Baldwin’s stepfather, Guy de Lusignan – thus strengthening the renown and influence of Richard’s troublesome vassals in the south of France and reinforcing the view that they were independent lords in their own right.

With Henry making it clear that he was staying to put his own house in order, family divisions surfaced once more with John’s departure to Ireland. Henry had instructed Geoffrey to return to Normandy and hold it in custody, possibly a sign that he intended a new configuration whereby he would formally unite Brittany and Normandy under one ruler, in combination with England and Anjou, leaving Aquitaine as an independent entity. Details of events in the spring of 1185 are somewhat unclear, but it seems Richard had once more mobilised his troops, forcing Henry to return to Normandy in April 1185. To all appearances, Henry was losing control of his lands and his sons, and he took drastic action to wrest control of Aquitaine back from Richard. Henry had brought his estranged wife over to the continent with him and ordered Richard that ‘he should without delay render up to Queen Eleanor the whole of Aquitaine with its appurtenances, since it was her inheritance, and that if he declined to comply, he should know for certain that his mother the queen would take the field with a large army to lay waste his land’. With the ultimatum issued, a family conference was arranged in May and Richard, ‘laying aside the weapons of wickedness, returned with all meekness to his father; and the whole of Aquitaine with its castles and fortifications he rendered up to his mother’. A form of peace then descended on the family, but as 1186 dawned it is hard to describe their relationship as anything other than dysfunctional, with any appearance of harmony to the outside world no more than superficial.

#

There were many factors behind the decline and fall of the Angevin dynasty in the early thirteenth century. However, we can trace the origins of the long war with Capetian France to 1186, when Philip increasingly sought ways to intervene – many would say interfere – in Angevin affairs. Henry should not have been surprised; from the very outset, Philip had shown an independent spirit in the way he tackled the influence of his mother’s family, and then wrested control away from his regent the count of Flanders, during the early part of his reign. Philip now signalled his intention to undermine the powers of Henry, as part of a longer plan to turn the nominal authority of the king of France over its traditionally independent vassals into a more practical version of reality. In March 1186, Henry and Philip held a conference at Gisors to resolve the outstanding issue of Richard’s marriage to Alice, given that they had been betrothed for a well over a decade; Philip agreed that the dower lands of the young king’s widow Margaret – the much-prized Norman Vexin – should transfer to Alice, thus providing an incentive for the marriage finally to take place. Henry and Eleanor returned to England, entrusting Richard with yet another campaign in the south, against the count of Toulouse.

The agreement at Gisors spelled trouble for Geoffrey; it seemed clear that Henry had reverted to his original plan of handing England, Normandy and Anjou to Richard. Running out of options within his own family, Geoffrey reverted to the tried and tested tactics and joined his close friend Philip in Paris to stir up trouble once more. He seems to have spent most of the summer at the French court, and it is likely that he was plotting with Philip, allegedly boasting in August, with typical bravado whilst they were preparing for a tournament, that he would lay waste to Normandy. However, tragedy struck; on 19 August, whilst involved in a mêlée during the staged combats, Geoffrey fell from his horse and was trampled to death. Philip was overcome with grief and, at his friend’s funeral, his household knights had forcibly to prevent him from flinging himself into the grave as well.

Geoffrey’s death marked a hardening of Philip’s attitude towards Henry. In September he demanded custody of Geoffrey’s two young daughters, and that Brittany be placed into his hands; a third child, Arthur, would be born posthumously in March 1187. He also sought to prevent any further military action against the count of Toulouse, making a veiled threat that he considered Henry’s actions tantamount to an invasion against a fellow vassal of the king of France, thus placing Normandy at risk of attack or even judicial confiscation. Henry backed down and a truce was agreed in October, but Richard was not recalled from the south until the two sides met again in February 1187, when a third cause of complaint was raised – Richard’s failure to marry Alice. Fuelled by rumours that Henry had seduced his son’s intended bride, and thus besmirched the dignity of Philip’s sister, Philip demanded the return of the Norman Vexin. This was now a Cold War turned hot. The disputed territory became the flashpoint for conflict between the sides for the next two decades; mercenaries were brought into the region, raising the tension as cross-border skirmishes became more common. Both sides arrested foreign-born nationals living in each other’s territories. Philip marched his army into Berry, where Angevin and Capetian rights and lands were intermingled, an act of military provocation that prompted Henry to mobilise his troops in response. The two sides faced each other in the fields outside Châteauroux, in full battle gear, on 23 June; the fate of two kingdoms hung in the balance. Pitched battles in the medieval period were very rare, especially between kings, given contemporary beliefs that trial by battle conferred divine judgment on the outcome; it is why Hastings holds such an important place in English history.

Châteauroux did not result in a decisive armed showdown. This was partly due to the presence of the papal legate Octavian, who was agitating for a truce because the pope wanted to secure the support of both parties for a crusade. The news coming out of the Holy Land had become increasingly grave, and unbeknown to the parties negotiating in the warm fields of France, time had already run out. On 4 July Guy de Lusignan was crushed by the forces of Saladin on the hot, dusty plains of Hattin; the crusader army was annihilated, Guy was captured and Jerusalem fell into Muslim hands, sending shockwaves around Europe. This was still in the future; Henry and Philip had other matters to occupy them during the shuttle diplomacy between the two armies facing each other at Châteauroux. Neither wished to climb down or lose face; the risk of battle remained real, and the atmosphere tense, as envoys passed between the camps. Many of the potential combatants were well known to one another, having competed on the tournament circuit or through shared family ties, and were therefore somewhat reluctant to engage in a fight to the death. In the end, diplomacy won the day and Henry conceded Philip’s right to two of the disputed lordships, and both sides agreed a two-year truce. However, one outcome from the stand-off at Châteauroux was of monumental importance – Philip had fatally undermined Richard’s relationship with Henry.

Philip’s agent of subversion was none other than the count of Flanders, a cruel irony given Henry’s attempts to patch up his relationship with the king of France during the early years of Philip’s reign. It was during the various negotiations in the meadows surrounding Châteauroux that the count drew Richard to one side to relay a personal message from Philip:

Many of us believe that you are acting extremely foolishly and ill-advisedly in bearing arms against your lord the king of France. Think of the future: why should he be well disposed towards you, or confirm you in your expectations? Do not despise his youth: he may be young in years, but he has a mature mind, is far-seeing and determined in what he does, ever mindful of wrongs and not forgetting services rendered. Believe those with experience; I too once ranged myself against him, but after wasting much treasure I have come to repent of it. How splendid and useful it would be if you had the grace and favour of your lord.

Think of the future – four words that struck at the heart of the issue and made Richard realise that he was the next generation, a young warrior compared to his visibly ageing father. His head was turned, and he agreed to meet Philip in person; when the negotiations were complete, Richard accompanied Philip to Paris where,

Philip so honoured him that every day they ate at the same table, shared the same dish and at night the bed did not separate them. Between the two of them there grew up so great an affection that King Henry was much alarmed and, afraid of what the future might hold in store, he decided to postpone his return to England until he knew what lay behind this sudden friendship.

As a gesture of political defiance, nothing could be clearer; once again, the king of France had driven a wedge between Henry and his eldest son, and he continued to exert a malign influence over Richard, planting the first seeds of doubt that Henry planned to disinherit him, or marry Alice to John.

In the days that followed the stand-off at Châteauroux, and as news of the fall of Jerusalem reverberated around Europe, attention briefly turned away from dynastic rivalry towards cooperative military and financial action in the Holy Land. Richard took the cross in November 1187, and superficially appeared to return to the family fold; the Saladin tithe was levied throughout England to pay for the upkeep of a crusading army. However, it was not long before Richard returned to his ceaseless battle for control in the south of Aquitaine, where yet another revolt had broken out in early 1188. It was also clear that Richard’s relationship with Henry had changed forever and he now acted alone, paying little heed to his father. Henry’s determination not to show his hand over the succession did not help; with only two sons left, and a general favouritism towards John, in whom he saw more of his own characteristics, it was now his policy to keep them guessing, further fuelling the sense of mistrust that Richard bore him.

It was in this atmosphere that entirely baseless rumours began to swirl around that Henry had deliberately stirred up new Lusignan opposition to Richard’s rule, which broke out around this time. Normally, Richard would have seen through this nonsense but it seemed that the slightest hint of interference had ‘alienated his mind from his father’. Philip turned the screw still further. Having defeated the Lusignans, Richard then continued his war against the count of Toulouse, yet it was to Henry that Philip addressed his displeasure over Richard’s actions. Henry responded despairingly that he had totally lost control of Richard and therefore, by extension, Aquitaine as well. Yet Philip could not – or would not – allow his own authority to be undermined by Richard’s unauthorised private war against a fellow vassal of the king of France, so in June 1188 he marched once more into Berry, seizing further Aquitainian lands in the disputed province.

This time, the sense of impending crisis refused to go away, despite Philip’s withdrawal from Berry after Henry raided his lands to the north. Negotiations failed to produce peace, with both sides raising the stakes; in a show of anger Philip even chopped down the ancient oak at Gisors where the king of France and duke of Normandy traditionally met for peace conferences. A further meeting in October similarly failed to provide a solution, with Richard angering his father by agreeing to have his dispute with the count of Toulouse heard in Philip’s court. This also marked the moment when Richard switched sides and

… became reconciled to the king of France because he had heard that his father wished to defraud him of the succession to the kingdom, in that he intended, as rumour had it, to confer the crown of the kingdom upon his younger son John. Disturbed by this, and small wonder, Richard tried to soften the mind of the French king, that in him he might find some solace if his own father should fail him.

The unfolding tragedy was thrown into sharp relief on 18 November at the next conference, arranged by Richard, at Bonmoulins; it did not augur well that Richard arrived in the company of Philip. The meeting was a tense affair. Although it started amicably enough, sharp exchanges became outright threats, leading knights on both sides to reach for their swords in case matters escalated still further. Philip once again demanded that Henry should arrange for Richard and Alice to be married, and declare Richard to be his heir; Henry angrily rejected the request, refusing to be blackmailed into having his family’s succession plans dictated to him by an outsider. At this, Richard turned to his father and asked to be confirmed as his heir, but Henry remained silent. Incredulous, Richard glared at him for a moment and then said, ‘I can only take as true what previously seemed incredible’ – indicating that he believed that he was about to be disinherited by his father. Slowly, he unclasped his sword belt and knelt before Philip and did homage for Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Aquitaine, Berry and lands in Toulouse – effectively usurping his father’s authority. The conference broke up in shock; Richard and Henry walked away from each other in opposite directions without a further word.

Despite an agreement to meet up again in January 1189, this was effectively a declaration of war, and a far more serious betrayal than in 1173 – this time Henry was old and clearly past his prime; Richard and Philip were the future, making it much harder for the old king to rally support. Nervously, he readied the defences of Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine; but when he held his Christmas court at Saumur, many of the usual attendees decided to stay away. Henry fell ill and cancelled the proposed meeting in January, but Philip refused to believe his excuse was genuine and began to wage war along the borders; the Bretons rose in rebellion, sensing an opportunity to exploit the situation to their own advantage and throw off the yoke of Norman dominance. In desperation, Henry sent envoy after envoy to Richard, entreating him to come back to his father, but by now Richard no longer believed anything that Henry said to him. Finally, another meeting was arranged on 28 May at La Ferté-Bernard in Maine. Richard and Philip laid down three conditions for peace – to the familiar demands for the marriage with Alice, and recognition of Richard as heir, was added a requirement that John should accompany his brother on crusade. Once again, Henry refused, perhaps believing that the presence of papal legate John of Agnani would help his negotiating position, given the threat of interdict hanging over Philip if he failed to reach agreement. However, Philip was not to be cowed and simply observed that the legate’s moneybags were full of English silver. The conference broke up once more, and Henry made his way slowly back to Le Mans.

The conventions of medieval warfare required Philip and Richard to withdraw to the frontier, but instead they seized La Ferté-Bernard and pressed on towards Le Mans, capturing castles as they went. On 12 June, they reached the outskirts of the city and, after a furious assault, broke into the lower town. In a desperate attempt to prevent the enemy forces from capturing the main citadel, the defenders set fire to the suburbs. However, the plan backfired as the wind changed direction, blowing the flames into the heart of the city. Before long Le Mans was a blazing inferno. Henry was able to make a hasty retreat with an armed escort, reaching a small hill a few miles to the north where he sat silently on his horse whilst he watched his birthplace burn; perhaps he was reflecting that the fate of Le Mans was an apt analogy for his relationship with Richard. It was too much for him, and he started cursing God for the fate that had befallen him. However, he did not wait long; although Philip halted the march, Richard continued to pursue his father towards Normandy. Riding hard, he caught up with Henry’s rearguard, under the command of William Marshal. Realising the danger, Marshal turned his horse and rode straight at Richard who shouted, ‘By God’s legs, do not kill me, Marshal. That would be wrong. I am unarmed.’ ‘No,’ replied Marshal, ‘let the devil kill you for I won’t,’ and ran Richard’s horse through with a lance, unseating him and making a clear point that he had spared Richard’s life. With the pursuit in chaos, the king’s party rode hard until they were within ten miles of Alençon, and the prospect of relative safety behind the stone walls of one of Normandy’s great fortresses where they could regroup.

Instead, and despite the exhortations of his closest advisors, Henry changed direction and made his way back south towards Anjou. He was a broken man, and no longer had the stomach for yet another cycle of rebellion, suppression and reconciliation. Whilst Philip and Richard overran Maine and Touraine, Henry finally reached his castle at Chinon, where, exhausted by the dangerous journey through enemy lines and fatigued by the heat, he succumbed once more to illness. On 2 July, French envoys reached Chinon and demanded a meeting so that terms could be discussed. Two days later, after Tours had also fallen, Henry agreed and they met at Ballon. However, he was crippled with pain, barely able to mount his horse; even Philip was moved to proffer his enemy a cloak so he could sit on the ground rather than discuss matters whilst mounted. Proud to the last, Henry refused and listened, propped up in his saddle by attendants, whilst Philip dictated the humiliating terms for peace. Henry was to place himself at Philip’s mercy, perform homage for all his continental possessions, recognise Richard as heir, arrange for Alice and Richard’s marriage once Richard had returned from the Holy Land, hand over various key castles as a sign of goodwill, and – the ultimate insult – pay Philip 20,000 marks indemnity for the trouble that had been caused. Henry agreed to everything, but Philip was not finished yet; he /had to give the kiss of peace to his son. As he leant forward to do so, Henry growled in a low voice into Richard’s ear: ‘God grant I die not before I have worthily revenged myself on you.’ Too exhausted to ride back to Chinon, Henry was borne away in a litter as thunder started to roll overhead, breaking the oppressive summer heat. Two days later, shattered by the news that his favourite son John had joined the rebellion against him, Henry was dead.