The Vikings in Wales

One side effect of the strength of Irish resistance was to increase Viking interest in Wales. At its closest points, Wales was only a day’s sail away from Dublin, Waterford and Wexford, and from the Viking colony in the Isle of Man, but despite this had so far suffered relatively little from Viking raids. A combination of strong military rulers such as Rhodri Mawr (r. 844 – 78) of Gwynedd, difficult mountainous terrain, and Wales’ poverty compared to England, Ireland and Francia, seem to have deterred any major Viking invasions in the ninth century. Only a dozen Viking raids are recorded in the period 793 – 920, compared to over 130 in Ireland in the same period. This was fewer than the number of English invasions of Wales in the same period. Place-name evidence points to areas of Viking settlement in the south-west, in Pembrokeshire and Gower, but, as they are undocumented, it is not known when they were made. There was also a small area of Viking settlement in the far north-east, modern Flintshire, most probably by refugees from Dublin following its capture by the Irish in 902. This was probably overspill from the successful Viking colony a few miles away across the estuary of the River Dee in Wirral.

In the first half of the tenth century, Wales was dominated by Hywel Dda (r. 915-50), the king of Deheubarth in the south-west. During his long reign Hywel came close to uniting all of Wales under his rule but his death in 950 was followed by a civil war and the break-up of his dominion. This was a signal to Vikings based in Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Hebrides to launch a wave of attacks on Wales. The area most exposed to Viking raiding was the large and fertile island of Anglesey off the coast of North Wales, which lay only 70 miles due east of Dublin and just 45 miles south of the Isle of Man: raids are recorded in 961, 971, 972, 979, 980, 987 and 993. Another place hit hard was St David’s monastery on the Pembrokeshire coast, Wales’ most important ecclesiastical centre. Founded c. 500 by St David, the monastery became the seat of the archbishops of Wales in 519. Only 60 miles from Wexford, St David’s was first sacked by Vikings in 967, then again in 982, 988 and 998, when they killed archbishop Morgeneu. St David’s would be sacked at least another six times before the end of the eleventh century. In 989 the raids had become so bad that King Maredudd of Deheubarth paid tribute to the Vikings at the rate of one silver penny for each of his subjects. Viking raids declined quickly after 1000, perhaps because the Viking towns in Ireland had come under the control of Irish rulers, but raids from the Hebrides and Orkney continued into the twelfth century. Vikings from Ireland also continued to come to Wales, but they did so mainly as mercenaries signing on with Welsh kings to fight in their wars with one another and with the English.

The Rock of Cashel

The end of Ireland’s Viking Age is traditionally associated with the rise of the O’Brien (Ua Briain) dynasty of Munster, and of its greatest king Brian Boru (r. 976 – 1014) in particular. Brian’s career certainly had an epic quality about it. Brian was a younger son of Cennétig mac Lorcáin (d. 951), king of the Dál Cais, whose kingdom, which was roughly equivalent to modern County Clare, was subject to the kings of Munster. As a younger son Brian probably never expected to rule and his early life was spent in the shadow of his elder brother Mathgamain. Even Brian’s date of birth is uncertain. Some Irish sources claim that he was eighty-eight when he died in 1014, which would mean he was born in 926 or 927, but other sources give dates as early as 923 and as late as 942. Brian’s first experience of war came in 967 when he fought alongside his brother at the Battle of Sulcoit against Ivar, king of the Limerick Vikings. The following year the brothers captured and sacked Limerick, executing all male prisoners of fighting age. The rest were sold as slaves. Ivar, however, escaped to Britain and in 969 he returned with a new fleet and regained control of Limerick only to be expelled again by the Dal Cais in 972.

Probably in 970, Mathgamain expelled his nominal overlord, Máel Muad the king of Munster, from his stronghold on the Rock of Cashel. The rock is a natural fortress, a craggy limestone hill rising abruptly and offering a magnificent view over the fertile plains of County Tipperary. The rock is now crowned by the ruins of a medieval cathedral and one of Ireland’s tallest surviving round towers, so little evidence of earlier structures survives. In legend, Máel Muad’s ancestor Conall Corc made Cashel the capital of Munster after two swineherds told him of a vision in which an angel prophesised that whoever was the first to light a bonfire on the rock would win the kingship of Munster. Conall needed no more encouragement and had hurried to Cashel and lit a fire. This was supposed to have happened around sixty years before St Patrick visited around 453 and converted Munster’s then king Óengus to Christianity. During the baptismal ceremony the saint accidentally pierced Óengus’ foot with the sharp end of his crozier. The king, thinking it was part of the ritual, suffered in silence.

Mathgamain’s success in capturing Cashel promised to make the Dál Cais a major power as Munster was one of the most important of Ireland’s over-kingdoms, covering the whole of the south-west of the island. However, before Mathgamain could win effective control of Munster, Máel Muad murdered him and recaptured Cashel. Brian now unexpectedly found himself king of the Dál Cais and quickly proved himself to be a fine soldier. After his expulsion from Limerick in 972, Ivar established a new base on Scattery Island, close to the mouth of the Shannon, from where he could still easily threaten Dál Cais. This sort of tactic had served Vikings well since the 840s, but no more. Brian had learned the importance of naval power from the Vikings and in 977 he led a fleet to Scattery Island, surprising and killing Ivar. A year later Brian defeated and killed his brother’s murderer to regain control of Cashel. Very shortly afterwards he defeated his last serious rival for control of Munster, Donnubán of the Uí Fidgente, and the remnants of the Limerick Vikings under Ivar’s son Harald. Both Donnubán and Harald were killed. This spelled the end of Viking Limerick. The town now effectively became the capital of Dál Cais, but Brian allowed its Norse inhabitants to remain in return for their valuable military and naval support. In the years that followed, Brian also became overlord of the Viking towns of Cork, Wexford and Waterford.

Now secure in his control of Munster, Brian began to impose his authority on the neighbouring provinces of Connacht and Leinster. Brian’s ambitions inevitably brought him into conflict with Dublin’s overlord, Máel Sechnaill. Almost every year, Brian campaigned in either Leinster, Meath or Connacht. Limerick and other Viking towns provided Brian with fleets, which he sent up the River Shannon to ravage the lands of Connacht and Meath on either side. When Donchad mac Domnaill, the king of Leinster, submitted to Brian in 996 Máel Sechnaill recognised him as overlord of all of the southern half of Ireland, including Dublin. Brian almost immediately faced a rebellion by Donchad’s successor in Leinster, Máel Morda, and the king of Dublin, Sihtric Silkbeard (r. 989 – 1036). Sihtric was another son of Olaf Cuarán, by his second wife Gormflaith, who was Máel Morda’s sister. Brian’s crushing victory over the allies at the battle of Glen Mama in 999 left him unchallenged in the south. Brian dealt generously with Sihtric, allowing him to remain king, and marrying Gormflaith, so making him his son-in-law. There was a brief peace before Brian, his sights now set on the high kingship itself, went back onto the offensive against Máel Sechnaill. Sihtric played a full part in these campaigns, providing troops and warships. Finally defeated in 1002, Máel Sechnaill resigned his title in favour of Brian and accepted him as his overlord: it was the first time that anyone other than an Uí Néill had been high king. Two more years of campaigning and every kingdom in Ireland had become tributary to Brian, hence his nickname bóraime, ‘of the tributes’.

The Battle of Clontarf

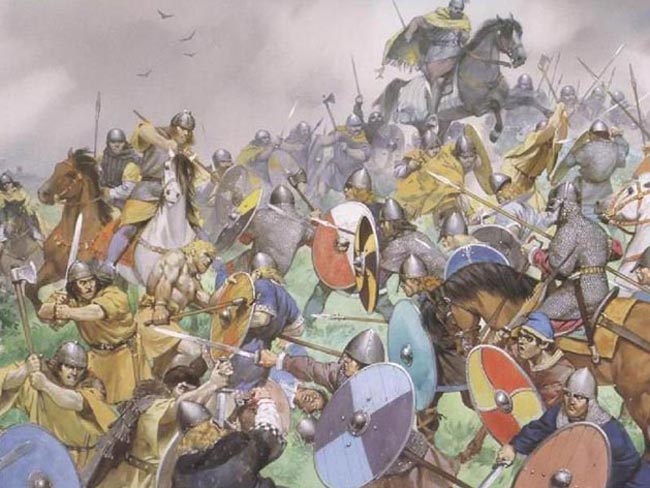

Brian’s achievement was a considerable one but he did not in any meaningful sense unite Ireland: outside his own kingdom of Dál Cais, Brian exercised authority indirectly, through his tributary kings, and he created no national institutions of government. Nor was the obedience of Brian’s tributaries assured: he faced, and put down, several rebellions. The most serious of these rebellions began in 1013 when Máel Mórda of Leinster renewed his alliance with Sihtric Silkbeard, who, despite Brian’s conciliatory approach, still hoped to recover Dublin’s independence. To strengthen Dublin’s forces, Sihtric called in an army of Vikings under Sigurd the Stout, the jarl of Orkney, and Brodir, a Dane from the Isle of Man, which arrived at Dublin just before Easter 1014. Brian quickly raised an army that included several of his tributary kings, including Maél Sechnaill, and a contingent of Vikings under Brodir’s brother Óspak. The two armies met in battle at Clontarf, a few miles north of Dublin on Good Friday (23 April) 1014. Neither Brian nor Sihtric fought in the battle. Sihtric watched the battle from the walls of Dublin, where he had remained with a small garrison to defend the city if the battle was lost. Now in his seventies or eighties, Brian was too frail to take any part in the fighting and spent the battle in his tent. The exact size of the rival armies is unknown but Brian’s was probably the larger of the two.

The battle opened around daybreak in heroic style with a single combat between two champion warriors, both of whom died in a deadly embrace, their swords piercing one another’s hearts. The fighting was exceptionally fierce but Brian’s army eventually gained the upper hand and began to inflict severe casualties on the Vikings and the Leinstermen. Brian’s son and designated successor, Murchad, led the attack and was said personally to have killed 100 of the enemy, fifty holding his sword in his right hand and fifty holding his sword in his left hand, before he was himself cut down and killed. Among Murchad’s victims was jarl Sigurd. Of the Dublin Vikings fighting in the army, only twenty are said to have survived the battle and the Leinster-Dublin army as a whole suffered as many as 6,000 casualties. By evening, the Leinster-Dublin army was disintegrating in flight and many Vikings drowned as they tried desperately to reach their ships anchored in Dublin Bay. At this moment of victory, Brodir and a handful of Viking warriors broke through the enemy lines and killed Brian as he prayed in his tent. Brodir’s men were quickly killed by Brian’s bodyguards and, according to Icelandic saga traditions, Brodir was captured and put to a terrible death. His stomach was cut open and he was walked round and round a tree until all his entrails had been wound out. Máel Mórda and one of his tributary kings were also killed in the fighting, as too were two tributary kings on Brian’s side.

For the anonymous author of the Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh, Clontarf was the decisive battle of Ireland’s Viking wars, but this exaggerates its importance. The author of the Coghad was essentially a propagandist for Brian Boru’s Ua Briain dynasty and he intended, by glorifying his achievements, to bolster his descendents’ claim to the high kingship of Ireland, which they contested with the Uí Néills. The true impact of the battle was rather different. The deaths of Brian and Murchad caused a succession crisis in Dál Cais that brought the rise of the Ua Briain dynasty to a crashing halt. Brian’s hard-won hegemony immediately disintegrated, Cashel reverted to its traditional rulers, and Máel Sechnaill reclaimed the high kingship. Sihtric found himself back where he had started his reign, a sub-king to Máel Sechnaill. There could have been no clearer way to demonstrate how far gone in decline Viking power in Ireland already was. Sihtric continued to take part in Ireland’s internecine conflicts but his defeats outnumbered his successes, and Dublin’s decline into political and military irrelevance continued. Dublin continued to prosper as Ireland’s most important port, however, making Sihtric a wealthy ruler. In 1029 he ransomed his son Olaf, who had been captured by the king of Brega, for 1,200 cows, 120 Welsh ponies, 60 ounces (1.7 kg) of gold, 60 ounces of silver, hostages, and another eighty cattle for the man who had conducted the negotiations. Though he was quite willing to sack monasteries when it suited him, Sihtric was a devout Christian and in 1028 he made a pilgrimage to Rome. Such journeys were primarily penitential and, as an active Viking, Sihtric no doubt had much to be penitential about. On his return to Dublin he founded Christ Church cathedral but pointedly placed it under the authority of the Archbishopric of Canterbury in England, then ruled by the Danish King Cnut. It was not until 1152 that the diocese of Dublin became part of the Irish church. His alliance with Cnut briefly resurrected Dublin as a power in the Irish Sea, but Cnut’s death in 1035 left Sihtric in a weak position. In 1036 Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, a Norse-Gaelic king of the Hebrides, captured Dublin and forced Sihtric into exile: he died in 1042, possibly murdered during another pilgrimage to Rome.

Echmarcach never succeeded in securing his hold on Dublin and in 1052 he was expelled by Diarmait mac Máel, the king of Leinster, who ruled the city directly as an integral part of his kingdom. For the next century Dublin became a prize to be fought over by rival Irish dynasties interspersed with periods of rule by Norse kings from the Isle of Man, the Hebrides, and even Norway.

Ostman Dublin

By the eleventh century the Viking towns had become fully integrated into Irish political life, accepted for the trade they brought and the taxes they paid on it, and their fleets of warships, which made them valuable allies in the wars of the Irish kings. Pagan burial customs had died out during the second half of the tenth century so it is likely that by now the Irish Vikings were mostly converted to Christianity. It was not only kings like Sihtric Silkbeard who had taken Irish wives, and in many cases the children of these mixed marriages were Gaelic speaking. It is even possible that people of Norse descent were minorities in the Viking towns among a population of slaves, servants, labourers and craftsmen that was mostly Irish. The Irish Vikings had become sufficiently different from ‘real’ Scandinavians to have acquired a new name, the Ostmen, meaning ‘men of the east’ (of Ireland). The name seems to have been coined by the English, who by this time had had ample opportunities to learn how to distinguish between different types of Scandinavian.

In its general appearance, Ostman Dublin was probably much like other Viking towns of the period, such as York or Hedeby in Denmark. In the tenth century the site was divided up by post-and-wattle fences into long narrow plots along streets. Sub-rectangular houses built of wood, wattles, clay and thatch were built end-on to the streets, with doors at both ends. Though the houses were often rebuilt, the boundaries of the plots themselves remained unchanged for centuries. Irish kings used these plots as the basic unit for levying tribute on Dublin, as Máel Sechnaill did in 989 when he levied an ounce (28 g) of gold for every plot. Paths around the houses were covered with split logs, or gravel and paving slabs. The streets of Ostman Dublin lie under the modern streets, so it is not known what they were surfaced with, but split logs were used in other Viking towns like York. Different quarters of the town were assigned to different activities. Comb-makers and cobblers were concentrated in the area of High Street, while wood-carvers and merchants occupied Fishamble Street, for example. Other crafts, like blacksmithing and shipbuilding, were probably carried out outside the town. The wreck of a Viking longship discovered at Skuldelev near Roskilde in Denmark proved to have been built of oak felled near Glendalough, 22 miles south of Dublin, in 1042.

The town was surrounded by an earth rampart, which was probably surmounted by a wooden palisade. By 1000, Dublin had begun to spread outside its walls and a new rampart was built to protect the new suburbs. By 1100 it had proved necessary to extend the defences again, this time with a stone wall that was up to 12 feet high. This was such a novelty that a poem of 1120 considered Dublin to be one of the wonders of Ireland. Dublin probably lacked any impressive public buildings – even the cathedral founded by Sihtric Silkbeard was built of wood and it would not be rebuilt in stone until the end of the twelfth century. Dublin’s four other known churches were probably also wooden structures. The basic institution of Dublin’s government, as in all Viking Age Scandinavian communities, was the thing, the meeting of all freemen. The thing met at the 40-foot (12 m) high thingmote (‘thing mound’), which was sited near the medieval castle. This survived until 1685, when it was levelled to make way for new buildings. Of the other Ostman towns, only Waterford has seen extensive archaeological investigations. Like Dublin it was a town of wooden buildings laid out in orderly plots within stout defences.

The end of Viking Dublin

Viking Dublin was finally brought to an end not by the Irish but by the Anglo-Normans. In 1167, Diarmait MacMurchada, exiled to England from his kingdom of Leinster, recruited a band of Anglo-Norman mercenaries to help him win back his kingdom. Reinforcements arrived in Leinster in 1169 and, with their help, Diarmait captured the Ostman town of Wexford. In 1170, Richard Fitzgilbert de Clare, popularly known as Strongbow, the earl of Pembroke, brought an army of 200 knights and 1,000 archers to support Diarmait, and within days he had captured another Ostman town, Waterford. On 21 September in the same year, Diarmait and Strongbow captured Dublin. The city’s last Norse king Asculf Ragnaldsson (r. 1160 – 71) fled to Orkney where he raised an army to help him win it back. In June 1171, Asculf returned with a fleet of sixty ships and attempted to storm Dublin’s east gate. The Norman garrison sallied out on horseback and scattered Asculf’s men. Asculf was captured as he fled back to his ships. The Normans generously offered to release Asculf if he paid a ransom, but when he foolishly boasted that he would return next time with a much larger army, they thought better of it and chopped his head off instead. Cork was the last Ostman town to fall to the Anglo-Normans, following the defeat of its fleet in 1173.

The Anglo-Norman conquest was a far more decisive event in Irish history than the advent of the Vikings. Despite their long presence in the country, the Viking impact on Ireland was surprisingly slight. Viking art styles influenced Irish art styles, and the Irish adopted Viking weapons and shipbuilding methods, and borrowed many Norse words relating to ships and seafaring into the Gaelic language, but that was about it. The Vikings certainly drew Ireland more closely into European trade networks and by the tenth century this had stimulated the development of regular trade fairs at the monastic towns. However, on the eve of the Anglo-Norman conquest, the Viking towns were still Ireland’s only fully developed urban communities. In contrast over fifty new towns were founded in the century after the Anglo-Norman conquest. Sihtric Silkbeard was the first ruler in Ireland to issue coinage in c. 997, but no native Irish ruler imitated his example: coinage only came into common use in Ireland after the Anglo-Norman conquest. The impact of Viking raiding did accelerate the slow process of political centralisation in Ireland, but even in 1169 the country still lacked any national government institutions. The high kings still exercised authority outside their personal domains indirectly through their tributary kings (though there were many fewer of them than when the Vikings had first arrived). A true national kingship would likely have emerged eventually, but the Anglo-Norman conquest brought this internal process to a sudden end. English governmental institutions were imposed in those areas controlled by the Anglo-Normans, while in those areas still controlled by the Irish, kingship degenerated into warlordism. There were no more high kings.

Dublin prospered after the Anglo-Norman conquest, becoming the centre of English rule in Ireland. England’s King Henry II (r. 1154 – 89) granted Dublin a charter of liberties based on those of the important English West Country port of Bristol. This gave Dublin privileged access to Henry’s vast British and French lands, spurring a period of rapid growth. One of Henry’s edicts took the Ostmen of Dublin and the other Norse towns under royal protection: their skills as merchants and seafarers made them far too useful to expel (though some chose to leave voluntarily). An influx of English settlers gradually made the Ostmen a minority in the city, however. The Ostmen also found that they did not always receive the privileges they had been granted because of the difficulty in distinguishing so many of them from the native Irish. In 1263, the dissatisfied Ostmen appealed to the Norwegian king Håkon IV to help them expel the English, but the collapse of Norse power that followed his death later that year ended any possibility that Dublin would recover its independence. Norse names soon fell out of use and by c. 1300, the Ostmen had been completely assimilated with either the native Irish or the immigrant English communities. A last vestige of the Viking domination of the city survives in the suburb of Oxmantown, a corruption of Ostmantown.