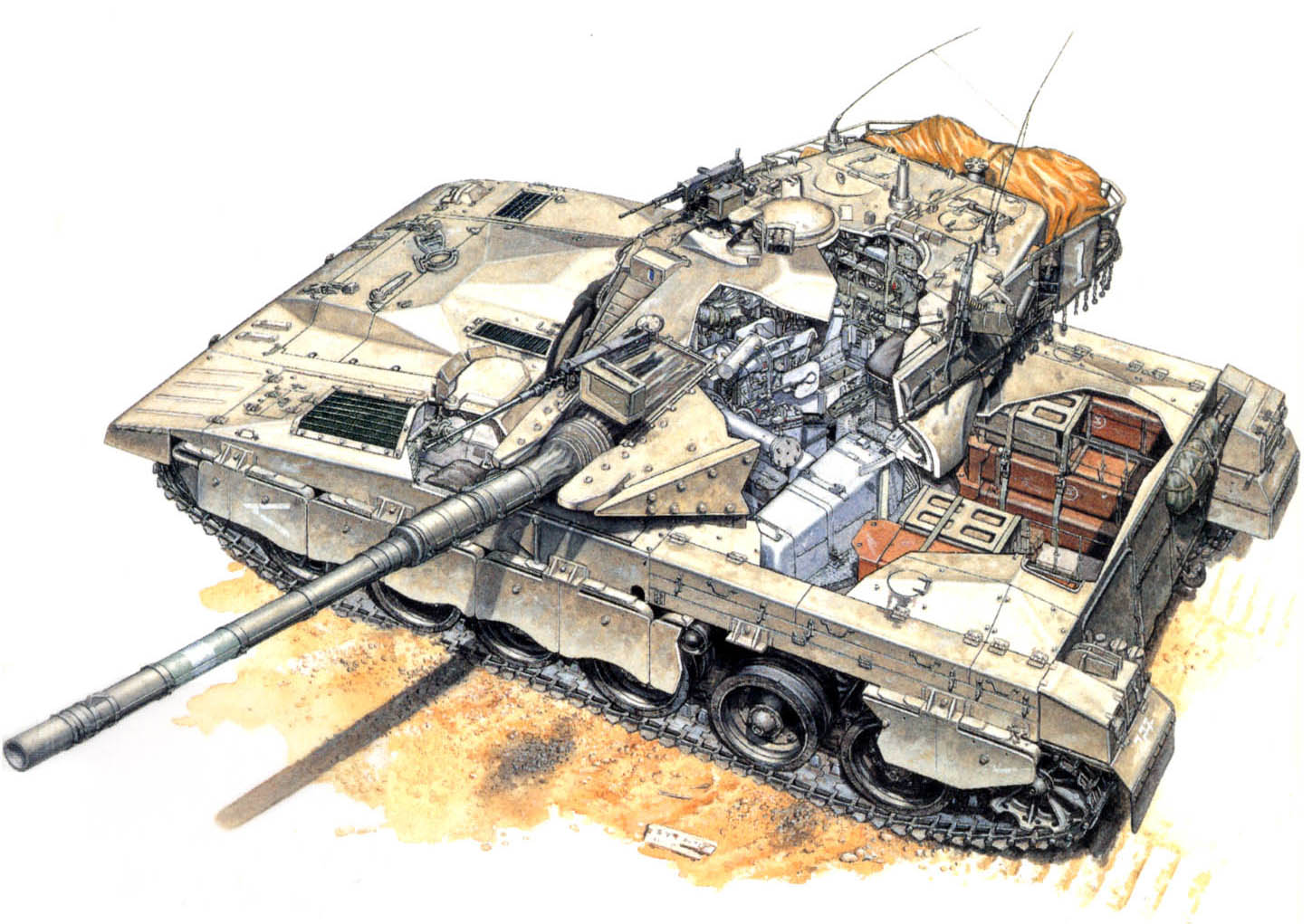

Merkava Mark II

The father of the Merkava project continued following global tank developments, and in the late 1980s he noticed that militaries were trying to come up with ways to make their tanks more accurate in motion. Talik understood that ground battles would not be the static engagements of World War II. The tanks needed the ability to shoot accurately at faraway targets not just while moving but while moving fast.

“You have to make the accuracy of shooting on the move like shooting when static. I want identical results,” Talik told Livnat one day. “The systems must give the commander operational freedom. I don’t want the commander to have to stop the tank in order to shoot and hit a target.”

Livnat was startled by Talik’s new request and dared to suggest that it was impossible. A tank in motion would not be able to hit targets as accurately as when standing still. “It’s delusional…” he said. But Talik believed it was possible and forced the engineers to hunt for a solution. Their work culminated in the development of a new fire control system called “Baz,” Hebrew for “falcon.”

“Talik didn’t have a strong tech side, but he had a sixth sense that wasn’t based on science,” Livnat told us. “Talik was a gunner in World War II and had a leather portfolio in his office with shooting tables, graphs used to track a tank’s hits and misses. He fired so many times in World War II that it became a second nature to him.”

What helped Livnat and his team find a solution was Talik’s recommendation that they focus on shooting-error factors, the reasons why the tank couldn’t stabilize the gun when in motion. Research revealed that the causes included the accuracy of the tank shells, the stability of the gun and the gunner’s ability to identify targets clearly while on the move.

Livnat ran dozens of experiments and discovered that the existing fire control system knew how to correct itself and overcome changes but that the gunner didn’t know how to take all of that into consideration. What this meant was that while the tank crew could measure the range, aim and shoot, the gunner couldn’t stay focused and would miss.

In 1989, Livnat and his team made their breakthrough. They developed an automatic tracking system combined with a video camera, which relieved the gunner from having to calculate the range and direction and allowed him instead to focus simply on when to pull the trigger. Only when confident that he was locked onto a target would he launch the shell.

Talik always pushed the needle a bit farther than it appeared able to go. This way, by demanding what seemed impossible, he would at least get a result close to what he wanted.

At the same time, Talik also gave independence to his engineers. He believed in his people, knew that they were experts in their specific fields and that, often, they knew better than he did what needed to be done to improve the tank. Once, when Livnat came to him with 30 proposed tank modifications, Talik had him split the list in half based on importance. When Livnat came back an hour later with the new list, Talik, who was busy reading some other documents, didn’t even look up. “Priority A is approved, priority B is not approved,” he said, determining the future of the tank as if ordering a deli sandwich.

#

From the beginning, Talik emphasized the need for the tank to be flexible and able to adapt constantly according to the changes Israel encountered on the battlefield.

For that reason, the tank underwent upgrades every few years until 2003, when the IDF deployed the Merkava Mk-4. A major improvement over earlier models, it could drive and shoot faster and, more importantly, it came with a new modular armor kit. This meant that the tank could be fitted with the armor it needed based on the specific mission it was heading into. An area known to have anti-tank missiles required heavy armor. An operation without the threat of anti-tank missiles meant less. This also allowed tank crews to replace damaged pieces of armor on the battlefield without having to bring the tank back to a repair shop in Israel.

The ability to adapt is a prominent characteristic in the IDF and stems from Israel’s limited resources. Unlike the US or some European countries, Israel cannot afford to simply shut down and open up projects as warfare changes. Instead, it needs to be able to extend the lifespan of its aircraft, navy vessels and tanks beyond the norm while ensuring that they adapt and remain relevant on the modern battlefield.

One change, for example, is in the targets Israeli tanks find themselves up against. In the past, tanks attacked other tanks. In today’s Middle East, Israel doesn’t have any enemies with tanks. Syria’s military is almost completely eroded after years of civil war, and Hamas and Hezbollah don’t operate tanks. This means that for tanks to remain relevant they have to be able to engage targets like a Hamas rocket cell hiding on the third floor of an apartment building or a Hezbollah terror squad hunkering down in a schoolyard.

To meet these challenges, the IDF has developed new weapons—sometimes satellite guided—that provide tank crews with the ability to strike buildings, anti-tank squads and even aircraft accurately. One such innovative weapon is the Kalanit, which can explode midair over terrorists hiding behind cover, or, alternatively, breach concrete walls and detonate only once inside a building.

What makes the Kalanit unique is the tank crew’s ability to choose two different modes for the way it wants the shell to detonate. On the one hand, it can be used like a traditional shell to target fortified structures or other vehicles and detonate on impact. On the other, it is useful for targeting terror squads, which cannot be effectively targeted by a standard tank shell. In this mode, the Kalanit can be programmed to stop midair, just over the terror squad, and then explode with six different charges, scattering thousands of deadly fragments.

Today’s tank also comes with the IDF’s advanced Tzayad (“hunter”) battle management system, basically a computer screen in the tank, which soldiers can use to see the locations of friendly and hostile forces. If a new enemy position is detected, all a commander needs to do is insert the location on the digital map. The position will then be seen by all nearby IDF forces—tanks, artillery cannons and attack helicopters.

A new version of the Tzayad software enables the system to recommend the type of munition that should be used to attack a specific target as well as the route a commander should take when leading forces into a combat zone.

Tzayad shortens the sensor-to-shooter cycle—the time it takes from when an enemy force is detected until the point when that force can be engaged. According to some estimates, the IDF has the cycle down to just a few minutes.

The biggest change, though, came in 2012, with the introduction of the Trophy, a system that could intercept anti-tank missiles fired at Merkava tanks. Until then, the world had heard of defense systems that could intercept ballistic missiles like the Arrow, but not one that could protect a single tank.

The idea was actually born in the 1970s, after the Yom Kippur War, during which IDF tanks suffered heavy losses at the hands of Egyptian anti-tank squads. One officer came up with an idea to install hollow explosive belts around the tank, which would detonate if struck by an incoming missile. This way the missile would explode outside the tank and fail to penetrate.

With the introduction of the Merkava tank a few years later, the idea was put on ice. The Merkava had unprecedented armor. It didn’t need an expensive active-protection system like the explosive belt.

But then came the Second Lebanon War and the Battle of the Saluki. While Defrin’s tank remained intact, the threat Hezbollah’s anti-tank arsenal posed needed to be dealt with. Intelligence showed that in Gaza, Hamas was learning the lessons from the war in Lebanon and was accumulating its own stockpile of advanced anti-tank missiles. And Syria was reportedly purchasing hundreds of motorbikes and training special forces how to ride and fire anti-tank missiles at the same time. These small, slippery targets would be difficult for tanks to locate and engage.

The belt idea was dusted off and handed to Rafael, a government-owned leading missile developer. The result was Trophy, a defense system that uses a miniature radar system to detect incoming missiles and then fires off a cloud of countermeasures—metal pellets—to intercept them. Trophy’s radar also interfaces seamlessly with the Tzayad battle management system. This means that Trophy can automatically provide the tank crew with the coordinates of the anti-tank squad that fired the missile so it can immediately be attacked.

In the summer of 2014, the IDF used Trophy for the first time in combat when Israel launched Operation Protective Edge against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. It was the most extensive use of Merkava tanks since the Second Lebanon War eight years earlier, when Effie Defrin almost died trying to reach the Saluki River. This time, though, the tanks were unstoppable. Dozens of anti-tank missiles were fired at Israeli tanks. Most missed and 20 were successfully intercepted by Trophy. Not a single tank was damaged.

Israel was once again changing modern warfare.

#

But why Israel? Why did Israel understand, over time, what other countries didn’t—that tanks could adapt and remain relevant even on the modern battlefield?

Part of the answer can be found in an old army base outside Tel Aviv. Called Tel Hashomer, the British base was captured by Israel during the War of Independence and became home to a number of units, including what is known as Masha, a Hebrew acronym that stands for the 7100th Maintenance Center, the place where the Merkava tanks are assembled and repaired.

Brigadier General Baruch Mazliach, commander of the Merkava Tank Directorate, recalls how as a young engineer he would wait in the field—sometimes even crossing enemy lines—for the tanks to return from operations. The engineers would examine every detail and debrief each tank crew member, thirsty for knowledge that would help them come up with ways to improve the tank. The engineers didn’t sit in air-conditioned offices and wait for the soldiers to come to them. They learned from Talik that the connection to the field was critical.

In his office, Mazliach keeps a brown file marked “Top Secret.” Its contents tell a story of a tank that was ambushed by Hezbollah in southern Lebanon in 1994. At one point, more than a dozen different types of missiles were fired at the tank, including mortar shells, which scored direct hits. Witnesses of the combined strike assumed that the tank would evaporate. There was no way, they thought, that the crew could sustain such an assault and survive. Clouds of smoke covered the entire area. The tank crew was feared dead.

Mazliach pulled a dusty photograph of the tank from the folder. “Each of the circles is a missile hit,” he told us. “This tank was mercilessly attacked from every direction, yet only one of the soldiers was killed. On the one hand, the outcome was fatal and harsh, but on the other hand, it proved how well-protected the Merkava really is.”

For the engineers like Mazliach, the tanks are not built for hypothetical scenarios. Those engineers spend time in the field, developing close relations with the soldiers and officers who serve in the tanks; often, the engineers’ own children are drafted into the Armored Corps. One engineer’s son was killed in an attack on a Merkava Mk-3. “We are like a family,” he explains. “That’s why everyone works 300 percent with their entire heart and soul.”

Being on the front lines of conflict since its inception, Israel often is the first Western country to face evolving and new threats, sometimes years before the rest of the world. The firing of Sagger missiles at Israeli tanks in the Yom Kippur War was the first real use of the advanced Soviet anti-tank weapon in war. The use of Kornet missiles by Hezbollah in 2006 marked one of the first times a terror organization had used tactics and characteristics that traditionally belonged to conventional militaries.

This leaves Israel with little choice but to constantly adapt to changing reality and to develop weapons, like Trophy, that can be applied as necessary. Israel doesn’t have the luxury to wait for these weapons to be developed somewhere else. It needs its tanks to fight, and it needs them to be protected.

That is why, in 2012, the IDF established a technical team to begin designing its future tank—aptly named “Rakia,” Hebrew for “heaven.” The significant expected changes will be in its mobility, crew size and fire-and-control systems.

But despite Israel’s continued technological developments, in January 2015, the IDF received a painful and stark reminder of the advanced arms that are circulating throughout the region. Hezbollah fired five Kornet missiles at an Israeli military convoy patrolling the border with Lebanon. Two soldiers were killed and seven were injured. Similar anti-tank squads are believed to be scattered throughout the nearly 200 villages in southern Lebanon, waiting for a future Israeli invasion. The guerillas are dressed in civilian clothing, living in regular homes. Attacks in a future war could come from anywhere—schools, hospitals and even ambulances.

In the Middle East, warfare is constantly changing. In Gaza in 2014, the IDF watched as Hamas terrorists jumped out of cross-border tunnels in surprise attacks; ISIS fighters in Syria drive commercial vans when attacking villages, and radical Salafi groups in the Sinai have succeeded in seizing armored personnel carriers for attacks on Egyptian military posts.

The key word for Israel remains “adaptation.” With the winds of war blowing along Israel’s borders, the next test of the Israeli Merkava is only a matter of time.