To this day, the Merkava tank is classified as one of Israel’s most top-secret projects. For decades it has been kept under a veil of secrecy, so that on “doomsday” it can be thrown like an iron monster onto the battlefield and defeat Israel’s enemies.

Many were involved in the development and production of the Merkava, but one IDF officer stands out: Major General Israel “Talik” Tal, the father of the Merkava tank.

Born in Israel in 1924, Talik learned early on what danger meant in the Land of Israel. It was 1929, and Arabs were rioting across the country. More than 100 Jews would be killed. One day, the doors to Talik’s home in the northern city of Safed were sealed off by a mob, and the house was set on fire. It seemed like the end, until Talik’s uncle ran up the street with a group of British policemen, who dispersed the mob. The uncle ran inside the house and rescued his five-year-old nephew. This near-death experience helped shape Talik’s life.

He volunteered for the British Army at the age of 17 and fought as a tank gunner in World War II. After the war, he joined the Israeli underground and helped purchase weapons for the soon-to-be state. In the War of Independence, he served as commander of a machine-gun unit and quickly climbed the IDF ranks—serving as commander of the Armored Corps, head of the Operations Directorate and the Southern Command and, eventually, a special advisor to the defense minister. Talik passed away in 2010. A plaque with his name hangs on a wall in the Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor in Kentucky, celebrating him as one of the five greatest armor commanders in modern history.

Israel’s search for a tank started with the establishment of the state. During the War of Independence, for example, soldiers from the IDF’s Seventh Brigade set off in unbearable heat to conquer Latrun, a former British police fort taken over by the Jordanian Legion. Despite numerous attempts, the IDF repeatedly failed to conquer the key site, which straddled the Jerusalem–Tel Aviv Highway. It simply lacked the means of penetrating the Jordanian fortifications.

Senior Israeli defense officials, politicians and lobbyists tried talking to Western countries about purchasing tanks for the IDF. Deals were reached, but threats of embargos were always in the air. Then came the Six Day War in 1967, during which Israel nearly doubled in size, conquering the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria. Israel knew it was only a matter of time before its neighbors tried to reclaim their lost territory. If it was going to win again, it would need a stronger Armored Corps.

After the war, the IDF received its first batch of French and then American tanks. In the late 1960s, Israel bought the Centurion, at the time the backbone of the British Army. Israel made a few modifications to the tank, installing an impressive 105-millimeter cannon and transforming its turret, giving it the name “Shot,” Hebrew for “whip.”

As part of the deal, Israel also received two Chieftains—Britain’s top-secret tank, still under development and equipped with a 120-millimeter cannon. After a series of trials, Israel was ready to make a deal for more, but then the British backed away, citing political considerations.

The British decision startled Israel. The Soviet Union was continuing to arm Egypt and Syria. Israel needed new tanks but didn’t have anywhere to buy them.

Cancellation of the deal left a deep impression on Talik. He understood that Israel had no one to rely on and came up with a revolutionary idea: Israel would build its own tank. Most people thought Talik was crazy. Until then, Israel had not built any of its primary military platforms—aircraft, navy ships or armored vehicles. But Talik insisted that it was possible. The study of the Chieftain had created some expertise in Israel, and Talik felt that there was a strong enough foundation to build on. He found a few partners and started creating a sketch of a tank. By 1969, the idea seemed viable. The question was whether it made financial sense and whether Israel really had the technology needed to develop a tank that could compete with the Soviet ones being supplied to Syria and Egypt.

In the summer of 1970, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, the Israeli war hero, and Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir met to rule on Talik’s tank idea. The meeting came after a team of security and economic experts had reviewed the proposal. All aspects of the project were studied: Was the tank Talik suggested even possible? and Would its development make economic sense for the fledgling state? For Sapir, the Merkava project had the potential to serve as a critically needed economic engine. The security benefit was secondary.

“I am for it,” Sapir told Dayan. “Do you want it or not?”

Dayan was concerned that the financial investment would overshadow other military projects and limit procurement plans. But in the end, he agreed and gave the green light for the first stage: development.

#

The blaring ring from the phone startled Lieutenant Colonel Avigdor Kahalani. It was the spring of 1971, and on the phone was a woman who identified herself as “Talik’s secretary.” A driver, she said, would be coming in the morning to pick up Kahalani for a meeting. He should be ready early in dress uniform.

The next day, a dark-green Plymouth Valiant—the army-issued car at the time for senior officers—stopped at the curb outside Kahalani’s home. The driver motioned for him to sit in the backseat. Kahalani did not have a clue what the meeting would be about, but it didn’t really matter. Talik was a legend in Israel. If he calls, you come. The car stopped at the entrance to a big warehouse in the Tzrifin Army Base south of Tel Aviv. Kahalani got out of the car just as Talik appeared swinging open the large iron gate, startling a flock of pigeons resting on a nearby building. He motioned for Kahalani to follow him inside as he pulled back a camouflage net covering something in the center of the large hall.

At first, Kahalani wasn’t sure what he was looking at, but after a few seconds it started to become clear. It was a tank, but not a regular one. This one was made of wood. The shape was strange as well. “The tank hasn’t got an ass,” Kahalani said. “Where’s the engine?”

Talik explained the rationale behind the new tank while walking in circles around his wooden creation. “It’s a new design. Engine and transmission in the front and an exit hatch in the rear,” he said. This was revolutionary. Until then, all tanks had their engines in the rear, and the entrance and exit from the tank was at the top of the turret, not at the back.

Talik had asked Kahalani to come see the tank so he could get the young officer’s support. Kahalani was one of the IDF’s up-and-coming armored commanders. He fought valiantly on his Centurion tank during the Six Day War and received the Medal of Distinguished Service. In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, Kahalani would make history as commander of the 77th Battalion, when he succeeded in repelling the Syrian assault on the Golan Heights.

When the Yom Kippur War broke out, Kahalani was already on the Golan. He managed to pull together about 150 tanks from various units and led them into battle against a Syrian force nearly five times the size of his. After several days of intensive fighting, Kahalani succeeded in stopping the Syrian assault, destroying hundreds of enemy tanks and reoccupying the dominant positions Israel had initially lost on the Golan. For his actions, Kahalani received the Medal of Valor, Israel’s highest military decoration. The meeting in 1971 was meant to reassure Talik that the tank he was building would be something young tankers—the likes of Kahalani—would want to fight in.

Even before the first kilogram of steel was poured, Talik envisioned the tank standing on the military parade ground ready for action. He didn’t let the pessimists—mostly the Treasury officials who were concerned that their money was going to waste—get to him. Step-by-step, he obtained the funding, knowledge and connections needed to establish a production line that could cast the tank body, manufacture the cannon and develop optics and fire-and-control systems.

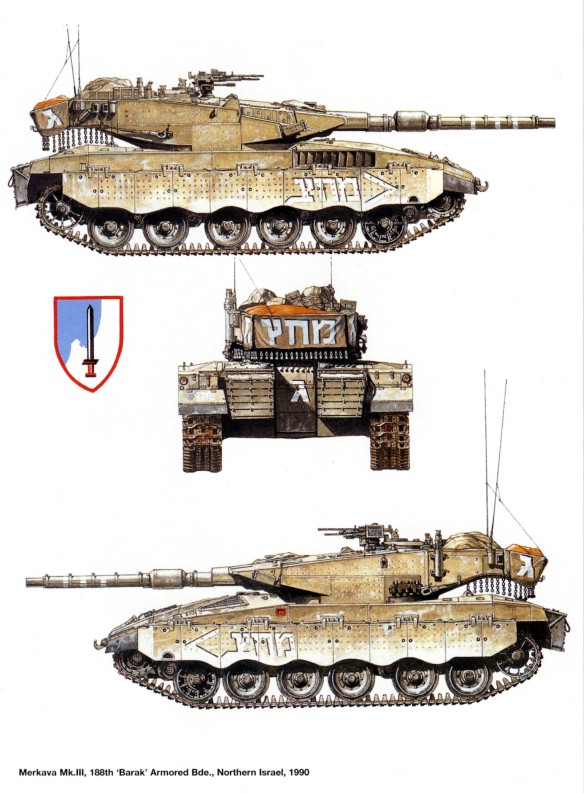

At the end of 1979, the first Merkava tanks were ready. Disagreements about upgrading the tank and correcting some remaining faults threatened to delay the project, but Talik’s determination and charisma swept obstacles aside. Three years later, the tank demonstrated its operational capabilities on Israel’s northern front during the First Lebanon War, and two years after, the second version—the Merkava Mark II—was already rolling off the production line. The Israeli tank had been born.

“We have the Jewish genome,” Talik used to tell his soldiers at the Merkava Tank Directorate. “This is what differentiates us from the rest of the world. However, this does not absolve us from learning. Only fools refuse to learn.”

Talik liked to surround himself with brilliant engineers like Yaron Livnat, a member of Israel’s “armor elite,” whose father had served as the head of the IDF tank maintenance unit. Livnat enlisted in the IDF as an academic and studied electronic engineering at the Technion. His dream was to invent new innovative missiles. But dreams only go so far, and after completing officer’s training, Livnat was assigned to the Tank Directorate. He thought it couldn’t get worse, but then Livnat was sent to join a real armor unit, out in the field.

Talik believed that technicians needed to be connected directly with the battlefield so they could understand the challenges soldiers faced and then come up with solutions that addressed real and not theoretical problems. Distance—whether cultural or physical—could not be allowed. Livnat was assigned to the Seventh Brigade for two months. He ran over hills while under fire, crawled in the sand, loaded tank shells and listened to the battle stories of his commanders and fellow soldiers. In his head, he was making a list of possible improvements that could later be implemented in the tank.

“No one understood what I was doing there. They thought there was something wrong with me. They told me it was idiotic to leave my office and go to the Golan Heights,” Livnat recalled. “I fully understood what I had to see and feel in the field. Not to mention the operational ties that I established with the soldiers and officers who later became battalion and brigade commanders.”

Talik liked Livnat since he saw that the young engineer had chutzpah, that he didn’t always toe the line, that for him, rules were usually just recommendations. Talik saw a bit of himself in Livnat. One day, Talik invited the young engineer for a talk and asked him to serve as his chief of staff.

Despite the compliment, Livnat politely refused, but insisted on explaining: “I am a young engineer. The technological side fascinates me. I must stay in this world.”

Talik wasn’t used to being rejected, but he appreciated Livnat’s candor.

“People like you, who tell me ‘no’; it is usually the end of their career. In your case, you’ll become my protégé,” he told Livnat.

Talik’s hard-soft demeanor enabled him to capture the IDF’s best and brightest. He was also a man of his word, and from that day forward, Livnat received backing to develop breakthrough systems. Talik nurtured him, and Livnat was appointed head of Merkava Mk-3’s Fire Control Project, a job that would ultimately win him the prestigious Israel Defense Prize.