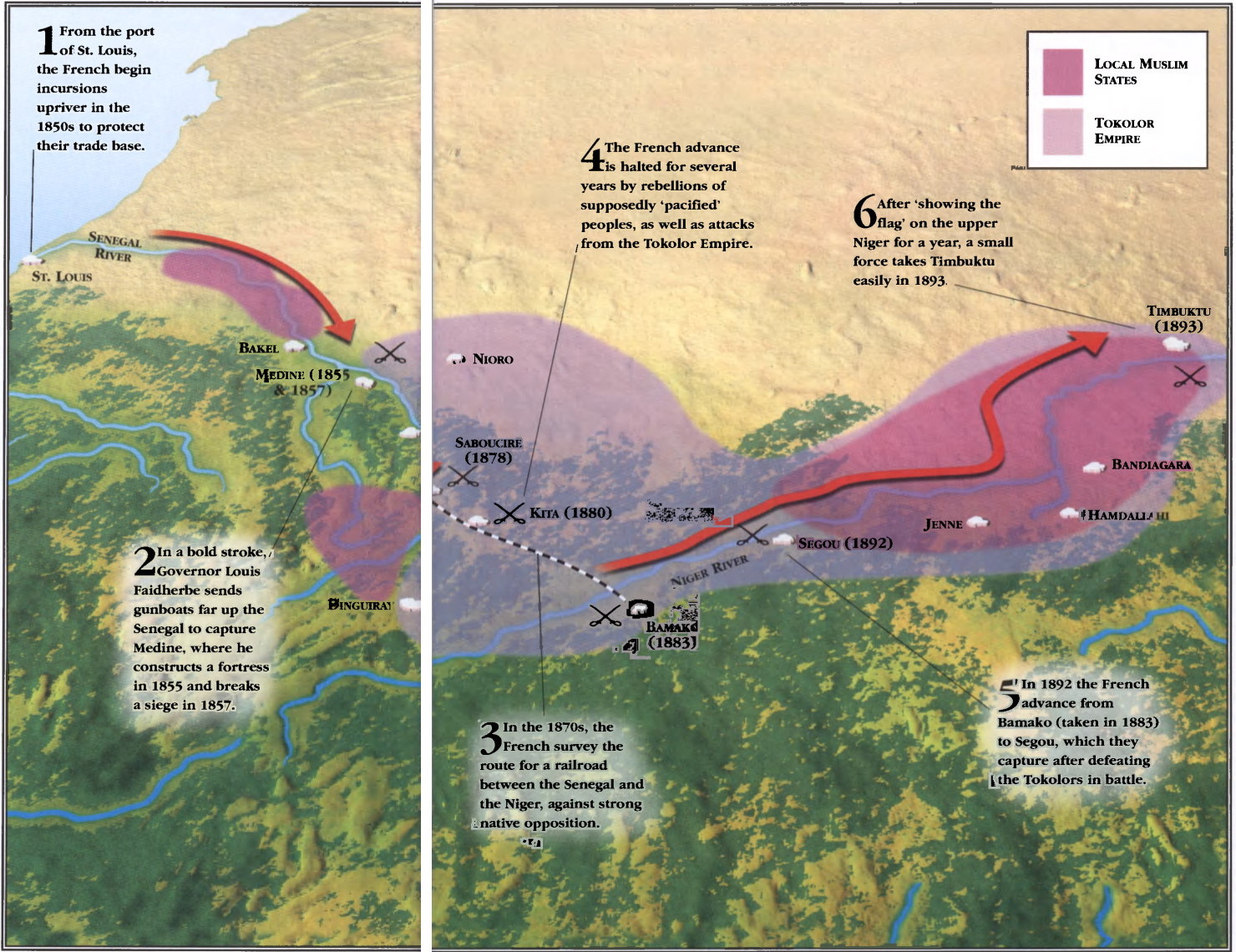

The French in West Africa. French incursions followed the paths of the Senegal and Niger rivers, greatly easing the problems of transport and logistics.

From his base at St. Louis, Governor Faidherbe moved his forces incrementally inland, taking advantage of the Senegal River for transport and access to the interior. The first action occurred in 1855, when French – commanded troops thrust far up the Senegal and established a fort at Medine; Faidherbe then secured the lower reaches of the Senegal with a series of forts. The French push inland raised the suspicions of Tokolor ruler al – Hajj Umar, who proclaimed an anti – European jihad. A plan for the conquest of the Niger Valley was revived in 1876. In 1878 a French force destroyed the Tokolor fort at Saboucire. Their goal was the Niger River, to which they carried dismantled gunboats while planning for a railroad link. They built a fort at Kita in 1880. After suppressing rebellions, the advance continued in 1886 with the capture of several Tokolor centres. The final stage was the seizure of Timbuktu in 1893.

West Africa

Both France and Britain were interested in West Africa for reasons that certainly had more to do with European rivalries and national pride than with trade. In the seventeenth century, the French established a trading post named St Louis at the mouth of the Senegal River. St Louis became a major slaving port, but by the 1820s the slave trade had been outlawed and entrepreneurs had to search for other trade goods. This soon brought them into conflict with the inland Tukolor Empire, which controlled the Senegal River to the bend of the Niger.

In 1852, the French Government authorized a drive towards the interior, the aim of which was to control inland trade to the exclusion of Berber and African middlemen. The commander of St Louis, General Louis Faidherbe (1818-1889), was left with a nearly free hand. In 1854, he began to establish forts along the Senegal River, which could be provisioned by boat and could control and protect shipping. The French offensive coincided with a major jihad in the Tukolor Empire under the leadership of al-Hajj Umar (1797-1864). The jihad’s primary enemy was animists, but a religious agenda soon became mixed up with fighting the French too.

French Outposts

By 1855, the French had established a fort at Medine, above the highest navigable point on the Senegal River, deep in Tukolor territory. In April 1857, Umar placed Medine under siege. When word of this act reached Governor Faidherbe, he set out to relieve the place in an expedition that is a model of riverine warfare in this period. Faidherbe packed 500 men into two armed steamboats. The vessels sailed upriver until they grounded, whereupon he lightened the steamers by disembarking the troops and marched them overland to rejoin the boats outside of Medine. A combination of an infantry charge and the steamboats’ cannonade drove the Tukolor forces from the fortress. This was a common pattern. A steamboat with its shallow draught could penetrate far upriver, carrying troops and supplies. Above all, steamboats could easily transport cannon and even early machine guns that would have been impossible to convey by land.

Perhaps the French in West Africa made so much use of riverboats because officers of the French Navy were so closely engaged in the colonial movement. During the Second Empire, it was French naval officers who got France embroiled in Indochina. In the Third Republic, it was above all the navy that promoted expansion in Africa, often by ignoring its civilian superiors.

A second French thrust into West Africa began in 1876, when the marine colonel Louis-Alexandre Briere de l’lsle (1827-1896) became governor of Senegal. His plan to establish a French West African empire was based on the ability to move men and materiel swiftly to problem spots, a plan that utilized both river shipping and railways.

In the 1870s and 1880s, both the British and the French pushed to control the Niger River, administrators in each country fearing that the other would take advantage of the decline of the Tukolor Empire. In the event, it was the French who first succeeded in opening the Niger River. French troops seized the fortress of Murgula on the Niger. They then carried a gunboat overland in pieces, reassembled it and launched it on the river. In 1891, the French added 95mm (3-7in) siege guns to their armament. These weapons were able to fire shells with the new high explosive melinite. This latest innovation could devastate the cities of West Africa.

The last stage of the French conquest of Western Sudan was the capture of Timbuktu in 1893- The city had declined sharply from its golden age but was still a formidable obstacle. In the event, the seizure of the city was a race between naval and marine forces. A marine colonel, Etienne Bonnier, proceeded against the city with two columns. Unwilling to share his glory, he ordered the two gunboats with the expedition, Mage and Niger, to remain at the anchorage at Mopti on the Niger. But Lieutenant Boiteux, who commanded the vessels, was eager for glory, too. Boiteux ignored his orders and sailed upriver to Timbuktu. The first troops in the city, on 16 December 1893, were a detachment of 19 sailors, who were welcomed as liberators. The army columns, rushing upriver in a fleet of canoes, reached the city later.

The Scramble for Africa

British and French competition for the Niger River valley led to a series of bitter territorial disputes. In the mid-1880s, the two nations decided on peaceable negotiation to divide West Africa between them. But the other European powers protested. The result was the Berlin West Africa Conference of 1884-85, which shared out much of Africa among the predatory imperial powers. However, an important point at the conference was that a nation could not claim inland territories without proof of effective occupation of the interior. The effect was to make gunboats on the rivers, and naval forces in general, more essential than ever.

Western naval forces were engaged in warfare through most of Africa, even in the absence of water. The reason was simple: navies contained large numbers of skilled artillerymen, since a warship was a large-scale floating battery. Navies were also quicker to adopt machine guns than were armies, because the weapons were heavy and difficult to transport on land, besides the fact that ships provided a fixed platform from which to fire. Thus, navies often provided special brigades to join army advances into Africa’s interior. For example, sailors formed a rocket corps in the Second Ashanti War (1873-74) and manned machine guns in Sudan in the 1880s. Sailors and their large ship guns were also a major contributor to victory against the Boers in 1899-1902. Thanks to the steam-driven gunboat, it was possible to accomplish extraordinary advances on the rivers of Africa, travelling into regions hitherto deemed impenetrable.

The Congo region was particularly inaccessible, thanks to a lethal mixture of swamps, rainforests and diseases. Welsh explorer Henry Stanley (1841-1904) was sent there in the late 1870s to negotiate treaties and establish a series of military posts for the Belgian king, Leopold II. At the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, the European powers granted Leopold an enormous independent state, if he could conquer it. The royal administrators put in place did so by controlling the Congo’s complex river system, creating a large fleet of river-going steamboats by the simple expedient of carrying gunboats overland. Stanley launched the first steamboat on the Congo in 1881; it had been carried overland about 400km (250 miles) in small, individually numbered pieces. Once reassembled, a gunboat could continue upriver 1450km (900 miles), to Stanley Falls, beyond which the Congo was navigable for another 800km (500 miles). Leopold’s Congo Free State developed a very expensive river fleet, using 90 per cent of the capital invested in the territory in the period from 1887 to 1896.

Mastery of the rivers allowed the Belgian controlled forces to move troops quickly. This mobility was decisive in the so-called Arab Wars of the 1890s, a very bloody series of engagements between the Congo Free State and Swahili slave traders. It proved easy for the Free State’s river fleet to reach the main Arab towns of Nyangwe and Kasongo.

More examples can easily be presented, especially from the 1880s and 1890s, when a new class of shallow-draught armoured gunboat was developed. The light cruisers and gunboats of the German Navy made it possible to establish German control in Cameroon and Tanganyika. In the 1890s, when British forces penetrated the Niger Delta region (southern Nigeria), naval vessels bombarded villages as well as providing necessary transport. The 1892 French invasion of Dahomey was greatly assisted by the gunboat Topaz, which steamed up the Oueme River parallel to the army’s advance. Even Portugal, in its conquest of Mozambique during the 1890s, made significant use of gunboats along the Incomati and Zambezi rivers.