The Battle of Kabul was less a battle and more a siege of the British cantonment outside the city. The British diplomatic mission, led by Sir William Macnaghten, superseded the military commander of the Kabul garrison, General Elphinstone, and dissuaded him from taking position within the Bala Hissar, the fortress in Kabul. Hostile Afghan tribesmen paid by Akbar Mohammed, son of the deposed king, Dost Mohammed, gradually surrounded the British encampment. There, they began bombarding the British position. A British foray against the Afghans failed, and later, Macnaghten was killed when negotiating terms.

Akbar Mohammed offered safe passage for the British garrison, and General Elphinstone naively accepted. En route to Jallalabad, the 16,000 soldiers and civilians were savagely attacked on numerous occasions. After eight days and a 96 km (60 miles) march, fewer than 300 soldiers remained. They made their last stand at Gandamak, only 55km (34 miles) from safety in Jallalabad.

Tension in Kabul

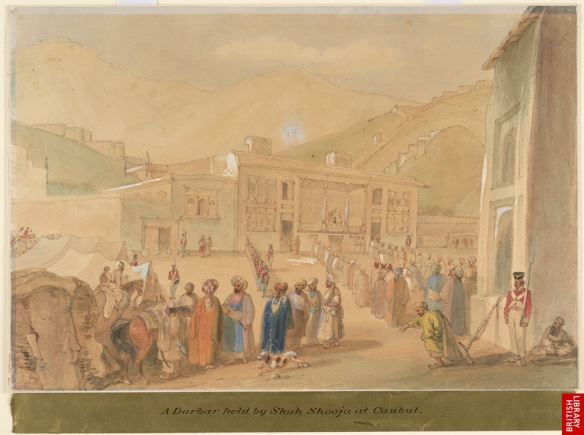

In the early nineteenth century, British expansion into India and what is today Pakistan ultimately involved Great Britain in local affairs well beyond the frontiers of its newly acquired south Asian empire. Russian and Persian encroachments into Afghanistan created potential crises on the Northwest Frontier. Internecine conflict among Afghan tribes and attacks from the Punjab further destabilized this region. In 1838, Britain entered into an official agreement with Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), ruler of the Punjab, and Shah Shuja (1785-1842), former ruler of Afghanistan. The Tripartite Treaty, of 29 July 1838, pledged restoration of Shah Shuja to the Afghan throne in return for a British diplomatic and military presence in Afghanistan at the expense of the Persians and Russians. In 1839, Sir John Keane (1781-1844) led the Army of the Indus, composed of British and Indian troops, through the Bolan Pass from Sind. Through the late spring and summer of 1839, Kandahar, Ghazni and Kabul fell. Dost Mohammed (1793-1863), the ruler of Afghanistan and a Russian client, was captured and taken to India. Shah Shuja returned to the throne after an absence of 30 years. A modest Anglo-Indian force remained to keep Shah Shuja secure, and protect Sir William Macnaghten (1793-1841) and Sir Alexander Burnes (1805-1841), envoys of Her Majesty’s government.

The events surrounding the fate of the Kabul garrison have become legendary – and considering the recent history of wars in Afghanistan, not unexpected. The success of the Tripartite Treaty gave a false sense of confidence to the government of Lord Auckland (1784-1849). The British army that arrived in Kabul with Shah Shuja was supposed to be temporary. The population of the city and the local tribesmen did not, however, find the presence of foreigners a comfort. The British, for that matter, ensured the security of their communications to India with a garrison in Jellalabad and the payment of tribute to the various tribal leaders who controlled the region through the Khyber Pass. The impressive military show during the invasion, the regular monetary gifts to local tribes and a sizeable garrison in Kabul provided the right amount of influence in Afghanistan. Yet, Akbar Mohammed (d. 1842), son of the deposed king Dost Mohammed, was determined to undermine British influence and restore his father to the throne. The British response (or lack of it) provided Akbar Mohammed with the opportunity to strike.

The British garrison at Kabul numbered 4500 British and Indian troops under General G. K. Elphinstone (1782-1842). The intent to keep a military presence in the city was abundantly clear to the population as the soldiers’ wives and families gradually migrated to the capital during the two years of occupation. Originally the garrison was established within the walls of the Bala Hissar, the fortress housing Shah Shuja’s palace. The shah, however, wanted to retain his own garrison and requested to Macnaghten that Elphinstone relocate his forces.

The British general acquiesced, as this was a diplomatic matter. The military encampment chosen was located north of the city, some 3km (2 miles) from the fortress, but the choice of location was quite poor. It was lodged between the Kabul River and the Behamroo Heights, which overlooked the camp. A series of stockade fortifications, which ringed Kabul, were within rifle shot of the cantonments.

General Elphinstone’s military career included service in the Peninsular War, at Waterloo and as aide to George IV Contemporary accounts before and after the events at Kabul refer to him as a professional and competent officer. It is clear, however, that the general’s command was complicated by several factors at the time of the crisis. He lacked energy, which some have attributed to his age, but he was only 59 at the time of his command. Several recollections refer to his indecision and passivity. Further, his orders were to maintain the formal presence in the capital, and protect Burnes and Macnaghten, the British envoys. This complicated matters, and Elphinstone tended to defer to the diplomats – a strategy that became fatal once the time for diplomacy had passed.

Akbar Mohammed benefited from the growing tensions among the Kabul population and local tribes towards the British presence. The cost of supplying the garrison fell upon the Afghan people, and this led to significant animosity. Furthermore, Sir Alexander Burnes had established a reputation as a scoundrel with women, and this merely incensed an already agitated population. All of this enabled Akbar Mohammed to increase his influence in the city and insinuate spies and agitators.

Route of the retreat. A garrison in Jellalabad secured the road from Kabul to Peshawar in British India. The distance, and nature of the terrain, made the route rather precarious, even in times of peace.

The situation escalates: November 1841 – January 1842

Elphinstone, Burnes and Macnaghten were well informed of the increasing tension in the city but refused to recognize the level of danger. The envoys believed the reports to be exaggerated, and Burnes, who lived in Kabul, believed he had a better understanding of the people than his informants and friends. On 1 November 1841, crowds gathered near Burnes’ residence, with the intention of causing trouble. News reached Macnaghten and Elphinstone, who immediately argued about the course of action. The general wanted to dispatch troops to disperse the mobs before they had a chance to build their courage. Macnaghten disagreed, and believed military action would only increase tensions. Elphinstone deferred, to the shock of his subordinates, and Burnes’ fate was sealed. The Kabul mob attacked Burnes’ home, and after a brief and violent struggle killed all inside.

The murder of Burnes did not lead to harsh reprisals; in fact, there was no response. Shah Shuja had hastily dispatched troops into the city, but they ignominiously retreated in the face of the violent mobs. Elphinstone failed to take any further military action, including dispatching troops onto the heights that dominated his encampment, or to occupy the forts within range of his tents. Unknown to Elphinstone, the British Government, wishing to pare down the cost of empire, had sought to reduce expenditure by ending tribute to the Afghan tribes: Macnaghten ceased paying the tribal leaders earlier that year. This offered Akbar Mohammed the opportunity to supplant British interests.

Afghan tribesmen began to occupy the heights, forts and villages around the encampment during the three weeks following Burnes’ murder. It was not until 23 November that Elphinstone finally acted. He was stirred by the deployment of two cannon on the heights, which proceeded to fire on the British camp. The general dispatched a flying column of infantry and cavalry, supported by one gun, to retake the heights and clear the village north of the camp. With relative ease, the Afghan cannon were put out of action, but upon passing beyond to the village, the column confronted Afghan cavalry.

The British gun overheated and the infantry formed in tight squares suffered heavy casualties from Afghan musketry. Growing pressure on the column caused the men to break ranks, and while order was restored, the position on the heights became precarious. Several charges served to further unnerve the British and Indian troops, who ultimately fled in panic back to the encampment. The failure to reinforce this column, although the combat was in clear sight of the cantonments, reflected a severe weakness in command – which encouraged the Afghans and demoralized the garrison.

Elphinstone and his subordinates discussed moving the garrison back into the Bala Hissar. This would have been the proper military decision, but again Macnaghten intervened. Shah Shuja was not inclined and found the situation quite troubling. The return of Akbar Mohammed meant the possibility of his overthrow, and the appearance of maintaining power on the bayonets of the British would not have reinforced his position among the population. Macnaghten dissuaded Elphinstone, and again the general deferred. The forces arrayed against them exceeded 30,000 men. By the end of November, Akbar Mohammed had arrived at Kabul with a further 6000 men. For the next month, he strengthened his hold over the tribal leaders, kept Shah Shuja trapped in the Bala Hissar and tightened his stranglehold over the British encampment.

Macnaghten, meanwhile, continued to hope for a diplomatic solution. He actively negotiated with the tribal leaders and Akbar Mohammed. At the end of December, the khan agreed to a personal meeting to decide the deadlock. Upon Macnaghten’s arrival, the British envoy was seized, along with his retinue, and murdered. General Elphinstone’s paralysis of command did not disappear with the death of Macnaghten. Instead, he became even more determined to negotiate a withdrawal of his garrison to India.

As negotiations carried on through New Year 1842, Akbar Mohammed acquired a greater appreciation of the weakness of the British position. Macnaghten had given the impression of strength, but Elphinstone’s disposition made it clear that the general would accept almost any reasonable proposal. In return for permitting safe passage for the garrison and their families to India, Elphinstone agreed to support the release of Dost Mohammed from British captivity.

The March of Death

On 6 January 1842, more than 16,000 soldiers and civilians from the Anglo-Indian garrison at Kabul marched off in the snows towards Jellalabad, the Khyber Pass and India. Jellalabad meant safety, but it was 150km (93 miles) to the east. Akbar Mohammed had no intention of keeping his word, and as the column moved off, it became clear that all bets were off.

The Anglo-Indian army winding its way methodically through the snows became the constant target of Afghan tribesmen. The advance guard led by the 44th Foot included Skinner’s Horse and the 4th Irregular Horse. The main body, with it the civilians, consisted of the 5th and 37th Bengal Infantry and Anderson’s Horse. The role of rearguard was left to the 54th Bengal Infantry and the 5th Bengal Cavalry. Impressive as these forces may sound, morale was terribly low, and the presence of families added to the soldiers’ concerns. Two days after leaving Kabul, the column moved through the Khoord-Kabul Pass, a narrow defile running 6.5km (4 miles) in length. There Afghan tribesmen took an enormous toll, firing from the safety of the heights. More than 3000 soldiers and civilians had been killed by the time Elphinstone cleared the pass.

Akbar Mohammed met Elphinstone afterwards, claiming that the attack was out of his control. He promised to try his best to prevent further murder, and offered to take women and children to safety. For the next several days, however, the survivors were subjected to attacks, and the weather too contributed to the disaster. On 13 January, the column approached Gandamak, some 55km (34 miles) west of Jellalabad, only to find its passage blocked. No more than 2500 of the 16,000 remained. Of that number, fewer than 300 were troops standing with their colours.

Elphinstone met with Akbar Mohammed once more, but found himself a prisoner. The survivors then took matters into their own hands, and tried to reach Jellalabad at night in two groups. They did not get very far. The larger group, many men of the 44th Foot and assorted Indian troops, made a stand on a hill near Gandamak. Refusing to surrender, they died where they stood. The smaller group made little progress and was soon overwhelmed. Only one survivor, Dr Brydon, managed to make it to Jellalabad, severely wounded but able to recount the tale of the doomed Kabul garrison. Elphinstone also survived but died in captivity some months after the debacle.