The initial Austrian manoeuvre took the Prussians by surprise. But Neipperg, rather than precipitate an attack with troops wearied from their march, chose to take up a defensive position around Mollwitz. Neipperg was not expecting an attack when late on the morning of 10 April he was informed that the Prussian columns were ‘uncoiling’ over the snowy fields. General-Leutnant Roemer, one of Neipperg’s more resourceful commanders immediately perceived the need to screen the Austrian infantry as it came into position and swiftly brought six regiments of cuirassiers forward where they shielded the main part of Neipperg’s force. At this stage the Prussian artillery opened fire on the stationary cavalry who, after receiving casualties, were ordered by Roemer to charge the right wing of the Prussian cavalry that had just come into view. The Prussian horsemen proved no match for the Imperial cuirassiers. An Austrian officer later recalled:

The Prussians fought on their horses stationary and so they got the worst of every clash. The extraordinary size of their horses did them no good at all – our cavalry always directed their first sword cut at the head of the enemy horse; the horse fell, throwing its rider to the ground who would then be cut down from behind. The Prussian troopers have iron crosses set inside their hats. These were splintered by our swords which made the cuts deadlier still. I might add that we had been ordered to sharpen most of our swords before the action and now their edges looked like saws.

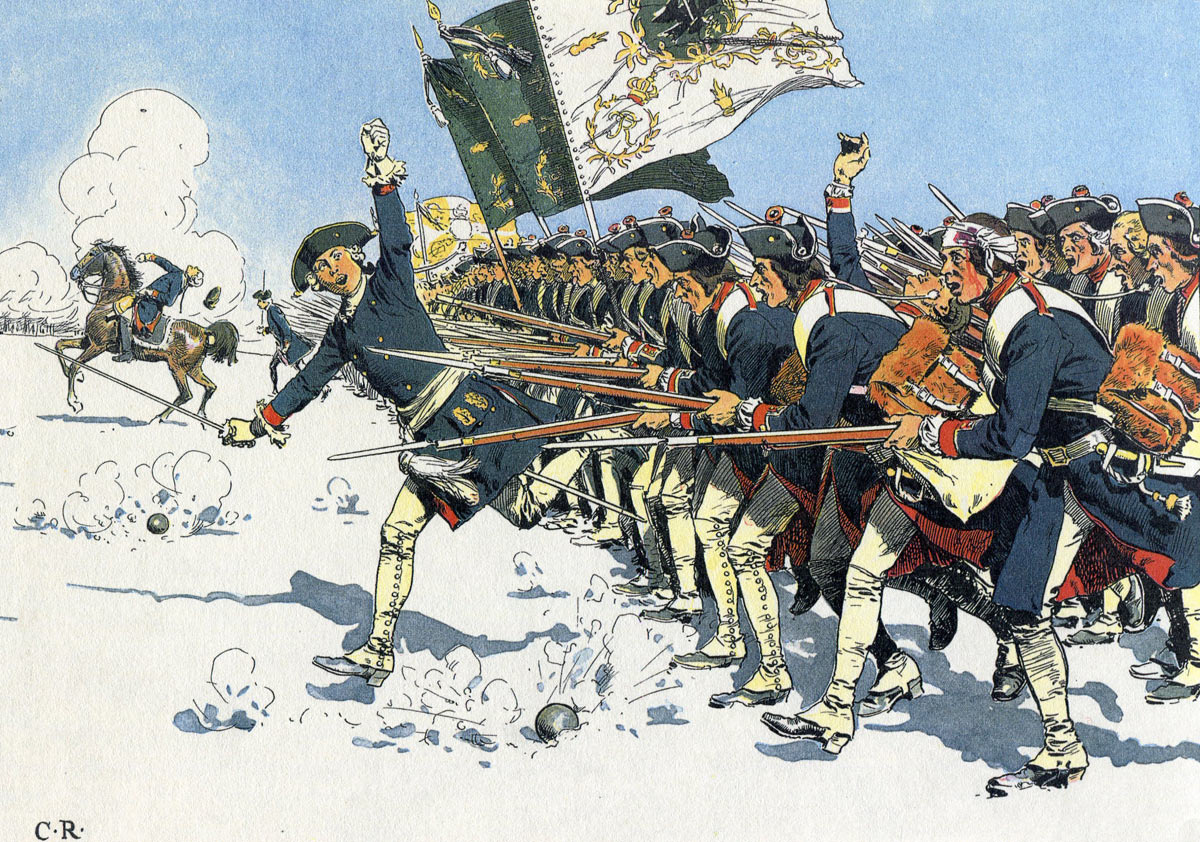

The exposed right wing of Frederick’s army began to crumble as Roemer’s men charged home. It was at this moment that Frederick, seized by panic as the Imperial cavalry penetrated his artillery park, decided to flee the conflict, leaving Schwerin to take charge. Schwerin acted swiftly to restore order on his right flank and hastily moved up three battalions, which in perfect drill formed a line and began to volley the disordered Austrian cavalry. Three times Roemer charged this Prussian line and each time his horsemen were repulsed, the last charge killing their commander. Unsupported by the Austrian infantry who were demoralised by the firepower of the Prussians, the Austrian cavalry fell back. Frederick’s infantry, though he was not there to see it, had not let their sovereign down. The Austrians, including Neipperg, had seen nothing like it. For every one volley the Austrian infantry loosed, the Prussians returned five. The effect was, after an hour, decisive.

‘Our infantry kept up a continuous fire,’ wrote an Austrian eyewitness, ‘but could not be made to advance a step. The battalions sank into disorder, and it was pathetic to see how the poor recruits tried to hide behind one another so that the battalions ended up thirty or forty men deep, and the intervals became so great that whole regiments of cavalry could have penetrated between, even though the whole of the second line had been brought forward into the first.’

Neipperg withdrew, his confidence in his troops almost as shattered as the morale of his men. The casualties for both sides together amounted to over 9,000, a figure regarded as considerable. Mollwitz had proved no simple victory for the Prussians and strategically it achieved little immediately. Frederick was unwilling to risk a second battle. Its effect on the Habsburg forces was nonetheless crushing.

Accounts of the weak showing of the Austrian infantry could not be entirely attributed to their being ‘made up of recruits, peasants and other poor material’. Maria Theresa would later write:

You would hardly believe it but not the slightest attempt had been made to establish uniformity among our troops. Each regiment went about marching and drilling in its own fashion. One unit would close formation by a rapid movement and the next by a slow one. The same words and orders were expressed by the regiments in quite different styles. Can you wonder that we were invariably beaten in the ten years before my accession? As for the condition in which I found the army, I cannot begin to describe it.

But though Mollwitz had hardly ‘cleared’ Silesia for the Prussians, news of the Prussian victory travelled across Europe, further encouraging various courts to deny the basis of the Pragmatic Sanction. In fact had Prussia lost Mollwitz the war and the bloodshed of the next two decades would have ended there and then; but fate decreed otherwise. While the Saxon army prepared to invade Bohemia, the French and the Bavarians advanced into Upper Austria. The dismemberment of the once ‘indivisible realms’ appeared inevitable.

Maria Theresa refuses to yield: the ‘King’ of Hungary

Calm resignation reigned at court. Somehow, under new rulers, the estates of the high aristocracy would survive. Life would go on and Maria Theresa would surely come to terms with just remaining an important Archduchess. Outside her domains no one preached appeasement more vigorously than England. A certain Mr Robinson was instructed by London to represent the dangers of failing to settle with Frederick. He was urged by the British government to ‘expiate on the dangerous designs of France … of the powerful combination against Austria’. But Mollwitz notwithstanding, Maria Theresa refused to yield. She listened patiently to Robinson but dismissed him with the words: ‘not only for political reasons but from conscience and honour I will not consent’.

It was only with the greatest of difficulty that Maria Theresa found advisers of backbone prepared to share her defiance. The news in June that Frederick had signed a treaty with France only made them rarer. Nevertheless, a handful stepped forward in the moment of crisis. Unsurprisingly we encounter yet again the name of Starhemberg but also Bartenstein and Khevenhueller, the grandson of Montecuccoli. In the moment of supreme trial the families that had had some connection with the Great Siege of Vienna in another moment of danger for the House of Austria two generations earlier once more stepped forward. But there were others, notably Count Emanuel Silva-Tarouca, a Portuguese aristocrat who never learnt German but became a kind of personal ‘coach’ to the Empress, advising her on every detail of her actions.

Another of these was an elderly shrewd Magyar by the name of Johann Pálffy, the Judex Curiae (Judge Royal) and the man whose moral authority in Hungary would prove Maria Theresa’s greatest support in this troubled year of 1741. Pálffy combined the qualities of statesmanship with the personal courage of a more martial calling. He too, like Starhemberg, had a name interwoven with battle honours, including the Great Siege of Vienna. He had taken part in most of the wars the Habsburgs had fought since then and had been wounded many times. He had also shown himself a keen diviner of the mysteries of the Hungarian temperament, negotiating the Peace of Szatmár with the insurgent Ráckóczi. At the same time, as a former Ban (viceroy) of Croatia, no one knew the mentality of that warlike people better than Pálffy.

Pálffy, like Khevenhueller was in the ‘sunset’ phase of his life in his late seventies – he would die in 1751. Nevertheless, he was deeply impressed by the young woman he served and saw that an approach to the Hungarian nobility was one of the keys to strengthening her position. It would also enable the Magyars to cement their own position advantageously vis-à-vis the Imperial house.

In accordance with Hungarian tradition, Maria Theresa would have to be crowned ‘King’ of Hungary (the Hungarian Constitution did not recognise a queen). The same tradition required then, as it would for nearly two more centuries, that the monarch mount a horse and ascend the ‘Royal Mount’ of Pressburg, some miles east of Vienna. Wearing the historic robes of St Stephen and the famous crown with its crooked cross, the sovereign was expected to take the slope at a brisk canter and, with the ancient drawn sabre of the Hungarian kings, point in turn to the four points of the compass, swearing to defend the Hungarian lands.

The story of the events of that 25 June in Pressburg and later in September have been much embroidered but we have, thanks to the hapless Mr Robinson – returned from his fruitless task to help Maria Theresa find a compromise with Frederick – a vivid eyewitness account of that day which gives us something of the flavour:

The coronation was magnificent. The Queen was all charm; she rode gallantly up the royal mount and defied the four corners of the world with the drawn sabre in a manner to show she had no occasion for that weapon to conquer all who saw her. The antiquated crown received new graces from her head and the old tattered robe of St Stephen became her as well as her own rich habit.

It was a good beginning to the eternally delicate Habsburg–Magyar relationship. Later that day as she sat down to dine in public without the crown, her looks, invested as they were with what one writer called ‘an air of delicacy occasioned by her recent confinement’, became ‘most attractive, the fatigue of the ceremony diffused an animated glow over her countenance while her beautiful hair flowed in ringlets over her shoulders’.

A little later on 11 September, having summoned the states of the Magyar diet to a formal assembly and once again wearing the crown, she appealed in Latin, the language of aristocratic Hungary at that time, to her audience, proclaiming in the language of the Roman Emperors, her speech:

The disastrous situation of our affairs has moved us to lay before our most dear and faithful states of Hungary the recent violation of Austria. I lay before you the mortal danger now impending over this kingdom and I beg to propose to you the consideration of a remedy. The very existence of the Kingdom of Hungary, of our own person, of our children and our crown are now at stake! We have been forsaken by all! We therefore place our sole resource in the fidelity, the arms and the long tried immemorial valour of the Hungarians.

The original of this speech exists and it is without doubt one of the most fascinating documents in eighteenth-century Central European history. It shows everywhere the young Queen’s hand over-working (in Latin!) the text of the original much less emotional speech prepared by her advisers. The word ‘poor’ for example is scratched out and replaced with the word ‘disastrous’. In almost every paragraph this girl, barely out of her teens, crosses out some anodyne formulation, replacing it with a more stirring phrase or word. Like a composer carefully judging structure and climax she transformed by a series of amendments a good speech into a brilliant one. As was to be so often the case, her instincts did not let her down.

What happened next is immortalised in countless paintings. Moved by the pleas of this young, helpless woman, the Hungarian nobles drew their sabres and pointing them into the sky cried: ‘Vitam nostrum et sanguinem pro Rege nostro consecramus’ (‘Our Life and Blood we dedicate to our King!’).

The drawing of swords was part of the ceremonial though clearly on this occasion injected with great passion. Who could resist the call of chivalry when articulated with such grace, and with feminine distress? Within a month Hungary had declared the ‘comprehensive insurrection’, pledging to take up arms to enter the war.

Even today we can sense the pulling of male emotional heart strings at which Maria Theresa so excelled in a letter to Khevenhueller penned around this time and sent with an accompanying portrait of herself and her son: ‘Here you have before your eyes a Queen and her son deserted by the whole world. What do you think will become of this child?’ In the first spontaneous response to this passionate outpouring of emotion on the part of the Magyars, it was estimated that perhaps as many as 100,000 men would flock to the cause. In the event it was to be a much more modest contribution, but significant nonetheless. Three new regiments of Hussars were raised, the first clad in exquisite chalk blue and gold, in the name and ownership of Prince Paul Eszterhazy.

Banalist and Pandour from the Corps of Colonel Trenck: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: Picture by David Morier

Habsburg irregulars: the Pandours

In addition, six regiments of infantry were raised. As well as the Hungarians there came another group of volunteers: the Pandours. These brigands, often the natives of the ‘wrong side’ of the Military Frontier, followed their leader, the gifted Baron Trenck. This Trenck is not to be confused with his kinsman who was initially in the Prussian service and whose memoirs were widely read in the eighteenth century. The Austrian Trenck pledged a unit of irregulars, a Freikorps (Free Corps) numbering about 1,000 to Maria Theresa’s aid.

These irregulars were welcomed into the Imperial service even though they possessed no conventional officer corps but a system whereby each unit of fifty men obeyed a ‘Harumbascha’. All the Pandours, Harumbaschas included, were paid 6 kreutzer a day out of Trenck’s own estates, a pitiful sum. This was certainly not enough for any semblance of a uniform and their appearance was highly exotic. When they appeared in Vienna at the end of May 1741, the ‘Wienerische Diarium’ could write:

Two Battalions of regular infantry lined up to parade as the Pandours entered the city. The Irregulars greeted the regulars with long drum rolls on long Turkish drums. They bore no colours but were attired in picturesque oriental garments from which protruded pistols, knives and other weapons. The Empress ordered twelve of the tallest to be invited with their officer to her Ante-Room where they were paraded in front of the dowager Empress Christina.

Neipperg found the Pandours rather raw meat. He was unused to the ways of the Military Frontier. On several occasions while campaigning he had to remind them that they were ‘here to kill the enemy not to plunder the civilian population’. The Pandour excesses soon provoked Neipperg into attempting to replace Trenck. The man chosen for this daunting task was a Major Mentzel who had seen service in Russia and was therefore deemed to be familiar with the ‘barbaric’ ways of the Pandours. Unfortunately, some Pandours fell upon Mentzel as soon as news of his appointment was announced and the hapless Major only escaped with his life after the intervention of several senior Harumbaschas and Austrian officers.

Mentzel, notwithstanding this indignity, was formally proclaimed commander of the Pandours, whereupon a mutiny took place which only Khevenhueller, a man of the Austrian south and therefore familiar with Slavic methods, could stem by reinstating Trenck under his personal command. At both Steyr and Linz, the Pandours in their colourful dress decorated with heart-shaped badges and Turkic headdresses would distinguish themselves against the Bavarians. Indeed, by the middle of 1742 the mention of their name alone was enough to clear the terrain of faint-hearted opponents. Within five years they would be incorporated into the regular army though with an order of precedence on Maria Theresa’s specific instruction ‘naturally after that of my Regular infantry regiments’. At Budweis (Budejovice) they captured ten Prussian standards and four guns.

The crisis was far from over. While Khevenhueller prepared a force to defend Vienna, the Bavarians gave the Austrian capital some respite by turning north from Upper Austria and invading Bohemia. By November, joined by French and Saxon troops, this force surprised the Prague garrison of some 3,000 men under General Ogilvy and stormed into the city largely unopposed on the night of 25 November. To deal with these new threats, Maria Theresa using Neipperg as her plenipotentiary had signed an armistice with Frederick at Klein Schnellendorf. She realised that her armies were in no condition to fight Bavarians, Saxons, French and Prussians simultaneously.

Maria Theresa received the news of Prague’s surrender with redoubled determination. In a letter to Kinsky, her Bohemian Chancellor she insisted: ‘I must have Grund and Boden and to this end I shall have all my armies, all my Hungarians killed off before I cede so much as an inch of ground.’

Charles Albert the Elector of Bavaria rubbed salt into the wounds by crowning himself King of Bohemia and thus eligible to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. The dismemberment of the Habsburg Empire was entering a new and deadly phase. Maria Theresa was now only Archduchess of Austria and ‘King’ of Hungary.

The election of a non-Habsburg ‘Emperor’ immediately provided a practical challenge for the Habsburg forces on the battlefield. Their opponents were swift to put the famous twin-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire on their standards. To avoid confusion Maria Theresa ordered its ‘temporary’ removal from her own army’s standards. The Imperial eagle with its two heads vanished from the standards of Maria Theresa’s infantry to be replaced on both sides of the flag with a bold image of the Madonna, an inspired choice, uniting as it did the Mother of Austria with the Mother of Christ and so investing the ‘Mater Castrorum’ with all the divine prestige and purity of motive of the Virgin Mary.

Another development followed: because Maria Theresa’s forces could no longer be designated ‘Imperial’ there emerged the concept of a royal Bohemian and Hungarian army which became increasingly referred to for simplicity’s sake as ‘Austrian’. The name would stick. When less than five years later Maria Theresa’s husband was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, Europe had become accustomed to referring to the Habsburg armies as the Austrians.

A glimmer of hope appeared as Khevenhueller cleared Upper Austria of the Bavarians and French. He blockaded Linz, which was held by 10,000 French troops under Ségur. And by seizing Scharding on the Inn he deprived the unfortunate French garrison of all chance of relief from Bavaria. The Tyroleans showed their skill at mountain warfare and ambushed one Bavarian force after another, inflicting fearful casualties. On the day that Charles Albert of Bavaria was elected Holy Roman Emperor, Khevenhueller sent the Bavarian upstart an unequivocal message: he occupied his home city of Munich and torched his palace.

Charles of Lorraine assumes command

Prince Charles of Lorraine, Francis Stephen’s brother and the descendant of the Charles of Lorraine who had played such an important part in raising the great Siege of Vienna, took command of the main Austrian force, hitherto under Neipperg. It was his first independent command and the fun-loving Prince, if contemporary accounts are to be believed, was uncouth, loud and a poor judge of character. It was quickly revealed that he was far from competent as a military commander. To Lorraine’s surprise and in breach of the treaty he had just signed at Klein Schellendorf, Frederick moved into Moravia, launching a full invasion of that picturesque province in February and linking arms with the French and Saxons in southern Bohemia. By the 19th he was at Znaim (Znojmo) barely a day and half’s march from Vienna.

Several thousand light cavalry were sent towards Vienna to scout and pillage. The panic in the Austrian capital was immense. Once again several prominent families contemplated flight but wiser counsels prevailed. Austria’s enemies could not agree on their shares of the spoils and Frederick, aware that he was overstretched, withdrew to a strong position in northern Bohemia. Here, eventually, Lorraine, after much prodding from Vienna, attacked at a village called Chotusitz. Once again the Austrian cavalry fought magnificently, overwhelming the opposing horse and driving it from the field. As the Austrian cavalry plundered the Prussian camp all was set for significant victory if the Austrian infantry could behave with cool discipline and attack. Unfortunately a certain over-zealous Colonel Livingstein had the idea of setting fire to Chotusitz, oblivious to the fact that the flames and smoke would effectively bring any attack to a halt and give the Prussian defence time to reform and hold their ground.

After four hours of heavy fighting Charles ordered his troops to withdraw. This they did in good order, having captured fourteen standards. The Prussians remained masters of the battlefield but their casualties were, at 7,000, no fewer than the Austrians’. The Prussian cavalry had been so severely handled that it was no longer an effective fighting force. This was not the crushing victory Frederick, who had finally distinguished himself during the battle by his courage and quick reactions, had wanted to support his demands for northern Bohemia.

The Prussians had been saved by the inability of their opponents to take advantage of at least three opportunities to crush them. Once again the Austrians for all the indifference of their leadership and discipline had proved themselves to be no easy enemy. Moreover the severity of the Prussian losses highlighted the asymmetry in manpower upon which both armies relied. The Austrians could draw on far greater numbers for recruitment and Chotusitz illustrated vividly Frederick’s dilemma were he to continue hostilities. As Count Podewils, Frederick’s courtier elegantly noted with regard to Austria, only ‘some lovely feathers had been torn from its wings’. The bird was ‘still capable of flying quite high’.

The situation in Bohemia was moving rapidly in Austria’s favour. The moment for rapprochement had arrived. Podewils signed the preliminaries at Breslau and Prussia gained Upper and Lower Silesia together with Glatz. The later Treaty of Berlin confirmed that only a sliver of Silesia around Troppau and Jaegersdorf was kept by Austria but Bohemia was secured and the Habsburg armies could now turn their full weight against their other enemies, notably the French.

These under Broglio had already retreated from Frauenberg, their baggage falling into the hands of Lobkowitz’s light cavalry. Seeking shelter in Písek, a French corps was compelled to surrender when a detachment of Nadasti’s Hussars, mostly Croats, swam across the river with sabres in their mouths and climbing on each other’s shoulders scaled the walls and first surprised and then began massacring the garrison.

Broglio sought to bring his harassed forces to Prague but here the condition of the French garrison was pitiable. Meanwhile, the coalition against Maria Theresa was breaking up. The Saxons no longer wished to be involved and the French and Bavarians had been outmanoeuvred on the Danube by Khevenhueller. Opinion in London and other parts of Europe was belatedly but finally rallying to Austria. The success of her armies and the character of her defiance added to the diplomatic awareness that only the House of Austria could check the ambitions of the House of Bourbon. With the removal of Walpole, the Austrian party once again was in the ascendant in London and large supplies of men and money were voted in parliament to support Maria Theresa. In Russia a new government watched how Prussia was developing with increasing scepticism.

At the same time in Italy, where both French and Spanish forces threatened Maria Theresa’s inheritance, a significant Austrian army assisted by the Royal Navy and the fine troops of the King of Sardinia drove their opponents out of Savoy, Parma and Modena. The Austrians here were commanded by Count Abensburg-Traun, governor of Lombardy and one of the more elderly of Maria Theresa’s generals. But though not in his prime, Traun was an able tactician and even Frederick admitted that the ‘only reason Traun has not defeated me is because he has not faced me on the battlefield’.

Traun had served as adjutant to Guido Starhemberg and as Khevenhueller noted:

From this experience he learnt how to conduct marches and plant camps with foresight and acquired the art of holding the defensive with inferior forces. Defensive operations were in fact his forte and he had few rivals in this respect. … The soldiers were very fond of him because he cared for their welfare and they invariably called him their ‘Father’. So generous was he towards his officers and the men that in later years he had almost nothing to live on and was virtually compelled to contract his second marriage so as to obtain a housekeeper and nurse.

All these successes offered the chance to conclude peace but Maria Theresa rejected all the overtures of the French. In front of the entire court she answered the French proposals with fighting words:

I will grant no capitulation to the French Army; I will receive no proposition or project. Let them address my allies!

When one of her courtiers had the temerity to refer to the conciliatory tone of the French General Belle-Isle, she exclaimed:

I am astonished that he should make any advances; he who by money and promises excited almost all the princes of Germany to crush me. … I can prove by documents in my possession that the French endeavoured to excite sedition even in the heart of my dominions; that they attempted to overturn the fundamental laws of the empire and to set fire to the four corners of Germany; and I will transmit these proofs to posterity as a warning to the empire.

The Siege of Prague continued and the French troops bottled up in the city became more and more desperate. Broglio escaped in disguise and Belle-Isle was left to effect the retreat. This he accomplished largely because of the incompetence of Prince Lobkowitz who, taking up a position with his army beyond the Moldau river, left only a small detachment of hussars to observe the French. Belle-Isle took full advantage of Lobkowitz’s complacency and stole away leaving only the sick and wounded. Eleven thousand infantry and 3,000 cavalry were thus extricated and passed some thirty miles through open country without receiving the slightest check.

In Prague even the wounded, amounting to some 6,000, rejected Lobkowitz’s furious demand for unconditional surrender. Their enterprising leader Chevert warned he would set fire to the city if he was not granted the full honours of war and Lobkowitz to his credit yielded, encouraged perhaps by the fact that his own magnificent palace with its priceless treasures would be the first to go up in flames.

But Belle-Isle had entered Germany at the head of 40,000 men and he returned to France with only 8,000, humiliated and a fugitive, a sorry outcome when an easy conquest had been anticipated.