Had the Turkish wars ended conveniently with the Habsburgs’ apogee at the Peace of Passarowitz in 1718, then the conventional assumptions about Ottoman decay and decline would have been triumphantly vindicated. But they did not end then. There were two more wars which destroyed the euphoric confidence generated by the victories won by the generation of heroes. The aggressive war fought against the Ottomans between 1737 and 1739, and the defensive war between 1788 and 1791, were probably the most pointless and inept campaigns in the annals of Habsburg warfare. In hindsight, both were ill considered, created solely to meet diplomatic expedients, by Habsburg officials with scant understanding of the military realities. Nevertheless, in 1737 the war began with huge optimism and a grand flourish.

On July 14 a great procession including representatives of the religious orders, judges, ministers, the court and the emperor himself wound its way from the Hofburg to St Stephen’s Cathedral to announce to the citizens of Vienna that war had broken out. Gathered before the great door of the church all heard the declaration of war and an edict proclaiming that the bells of the city churches would ring every morning at 7.00 and each individual was to fall to his knees wherever they were and whatever they were doing and pray for the blessing of the Almighty upon the army of the emperor.

This was the only part of the war that passed off according to plan.

All along the long frontier there were inadequate supplies, not enough troops, and, by late August 1737, no evidence of a plan of campaign. The Austrians were dilatory in attacking the Turkish fortress of Vidin, which would have fallen to a swift attack, while a thrust into Bosnia to take the town of Banjaluka ran into a large Ottoman force and had to retire rapidly on the far side of the River Sava, leaving 922 men and 66 officers dead on the battlefield. The final failure of the year was truly humiliating. The only real success of the campaign had been taking the strategic town of Nish, on the road south to Istanbul. The pasha there had surrendered as soon as the Austrian army had appeared. In Vienna the seizure of such a famous town as Nish had been taken as a great victory, and confirmation that the Ottomans had indeed lost their old fighting spirit.

But in October 1737 a mass of Turkish sipahis arrived before the city and sent a message to the commander that the Grand Vizier, Ahmed Köprülü, was on his way with his entire army. General Doxat calculated that supplies were low and he had no hope of relief: when Köprülü arrived, Doxat offered to surrender the city in exchange for a safe conduct to Austrian lines for his men and himself. This appeared to be precisely the kind of craven conduct that the Turks had shown when they had given up the city in July 1737. There was popular outrage in Vienna at this cowardice: after a swift court-martial, Doxat, who had designed and built the massive new fortifications protecting Belgrade, was beheaded.

Doxat was not the last officer to be punished. By the end of the war in 1738, every senior commander had been cashiered, suspended from duty or lampooned in the press. Public outrage in Vienna grew as rabble-rousers asked: `Where is the new Eugene?’ The old prince had died barely two years before. He had no obvious replacement. The field commander, Field Marshal Seckendorf, was recalled and placed under house arrest to await court martial. He was a Protestant, and Father Peikhart preached from the pulpit of St Stephen’s that `a heretical general at the head of a Catholic army could only insult the Almighty and turn his benediction away from the army of his Imperial and Catholic Majesty’. For reassurance that the dynasty’s Catholic credentials were still paramount, the Emperor appointed his son-in-law, Francis Stephen of Lorraine, to the titular command for the 1738 campaign season, and he left for the southern frontier. This failed `to win the people’ until it was reported that young Lorraine had `issued orders calmly under fire’: at this point the court hailed him both as a second Eugene (unlikely) and as a true grandson of Charles V, Duke of Lorraine, who had saved Vienna in 1683.

Soon Seckendorf ‘s replacement, Count Königsegg, also suffered a loss of nerve and ordered a strategic withdrawal away from contact with the Ottomans; his junior officers protested, demanding he should pursue the enemy as Prince Eugene would have done. The Emperor decided that his inexperienced son-in-law possessed better credentials to lead the army to victory and gave him full command. Francis Stephen wisely fell sick and returned to Vienna, so the duty devolved back on Königsegg, while Francis Stephen and his wife, Maria Theresa, were rusticated to their duchy of Tuscany, to their delight. Meanwhile, the Emperor was `in the middle of the general discontent . . . violently agitated and in the agony of his mind exclaimed “Is the fortune of my empire departed with Eugene?”‘ He continued to look for a commander with some spark of daring. Running out of plausible candidates, he eventually chose Field Marshal George Oliver Wallis, of an old Jacobite family with a long record of service to the Habsburgs. Wallis had fought under Eugene at Zenta in 1697, at Petrovaradin, in the capture of Timi, soara, and at the occupation of Belgrade in 1717-18. He had been passed over before because he was not an easy subordinate: difficult, overbearing and hot-headed. His first instinct was to attack, although he had learned a degree of prudence in his later career. If Charles VI wanted a new Eugene, then the elderly Wallis was probably his best option.

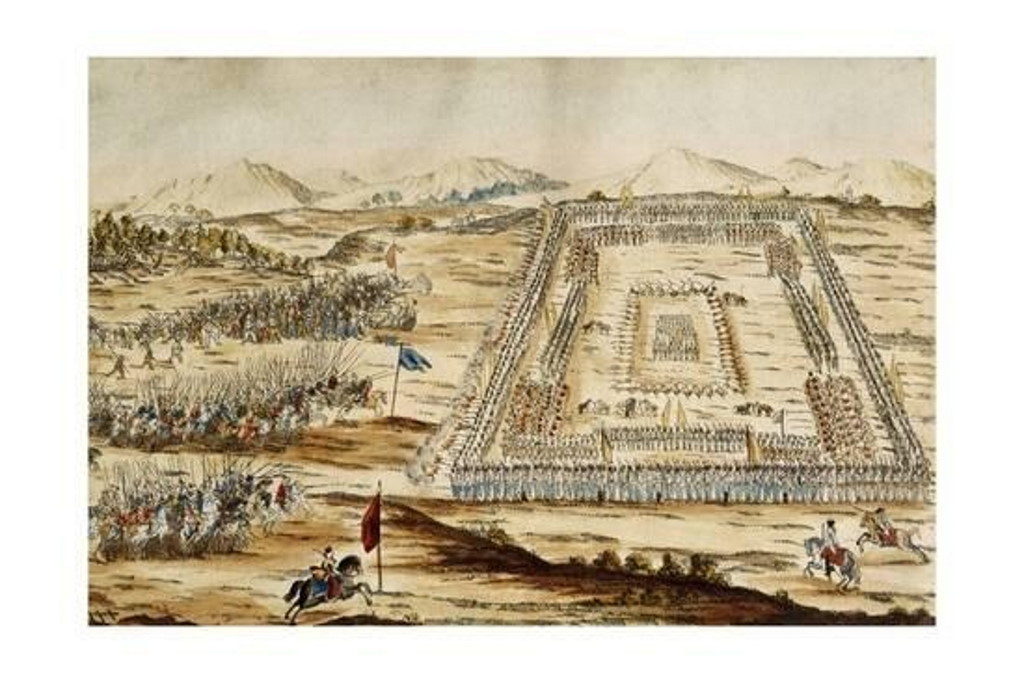

By mid-July 1739 he had joined his new command of thirty thousand men encamped at Belgrade, and scouts brought him news that the Grand Vizier’s army was marching towards him from the east: their advance party was at the small town of Grocka on the Danube, a few hours’ march away. The events that followed were graphically described by a Scots officer in the British army on secondment to the Austrian command. The young Scottish nobleman, John Lindsay, 20th Earl of Crawford, had fought as a volunteer with Prince Eugene on his last western campaign in 1735, and joined the eastern army for the war in 1737. He left a remarkable manuscript account of the savage fighting. As Crawford relates, part of Wallis’ army was still north of the Danube with General Neipperg, and the advice was that he should wait for the additional 15,000 men to reach him. Wallis sent a messenger to Neipperg to meet him on the road to Grocka and began to march his men overnight to seize the village from the few Turks that supposedly held it. Then he could await the Grand Vizier on ground he had chosen. It was a good road from Belgrade through low hills, and it began to rise towards a line of higher ground behind Grocka.

Just before the village, the track narrowed and entered a gully that then opened out on to the plain before reaching the riverside town. It then came out in a southerly direction, heading towards higher ground. Wallis knew that speed was essential so he pushed forward with the cavalry – mostly cuirassiers and dragoons, with some hussars – sending them through the gully to take possession of the land below, driving away any Turks occupying the ground. Led by Count Palffy’s cuirassiers, they burst out of the gully and began to trot down into the more open ground in front of Grocka. It was first light, and they dimly saw a large body of men below them and then there was a sudden cacophony of fire from the front and from each side of the road. They still had the advantage of the higher ground, but it was clear that this was not just an Ottoman advance party. In fact the entire Ottoman force had taken up position on the hills and in the valley below, with a complete command of the road in front of the Austrian horsemen. Many had been killed or wounded in the first salvo of Turkish fire, and the ground was littered with dead or dying men and horses.

One of the wounded was the Earl of Crawford. He survived the battle, but was seriously injured by a musket ball in the groin, a painful, suppurating wound that would kill him ten years later. In the interval he managed to write his vivid account of the battle and what followed.

From dawn to mid-morning they kept the janissaries at bay, by constant carbine fire and support from the troops behind. At midday the infantry arrived, and eighteen companies of grenadiers pushed through the gap and heavy fire to relieve them. Through the morning the Grand Vizier had ordered men to move forward up the slope to the crown of the hills on either side of the Austrian cavalry so that they could envelop them, unleashing musket fire from directly above their makeshift positions. On the other side of the gully, Field Marshal Hildburghausen, in command of the infantry, ordered his men to storm the heights and throw the Turks back. Field guns were pulled up the slope and began to duel with the Ottoman artillery on the hillside opposite. The battle lasted the whole day, with more and more of the Austrians pushing through the gully while the Ottomans kept up a murderous fire. As night fell, the Grand Vizier pulled his men back in good order and, apart from the cries of the wounded, a still ness fell over the battlefield. The carnage was horrifying: in a single day from dawn to dusk, 2222 Austrians were dead and 2492 wounded. This was more than 10 per cent of Wallis’ entire force. The Palffy cuirassiers had lost almost half their number, including the majority of their officers. Even a year later, it was still like a charnel house. A traveller described how `Today one cannot go ten steps without stepping on human corpses piled on top of another, all only half decomposed, many still in uniforms. Lying about are maimed bodies, hats, saddles, cartridge belts, boots, cleaning utensils, and other cavalry equipment. Everything is embedded in undergrowth. In the surrounding countryside, peasants use skulls as scarecrows: many wear hats, and one even wears a wig.’ Some of Wallis’ senior officers suggested a hot pursuit, but he rightly feared another ambush: he did not want to face the Ottomans, now in the hills, again from positions designed to entrap him, as they had done so successfully at Grocka.

So a third campaigning season degenerated into a fearful torpor, only to be crowned by the ultimate misfortune. Belgrade, taken in 1717, had been turned into a fine town, but only for German speakers; it had been brilliantly fortified by the luckless Doxat. In the chaos of the campaign, it was surrendered by mistake to the Turks. The Grand Vizier, negotiating in his camp with Neipperg, managed to persuade him that the Ottomans were bound to capture the city, and, to save lives, it should be surrendered to him immediately. Neipperg eventually agreed, extracting a single concession. The fortifications built since the Treaty of Passarowitz, paid for by the Pope and Catholics throughout Europe, would be demolished so they did not fall into infidel hands. The vizier readily agreed, provided his janissaries should first occupy the gates and walls of the citadel.

After this agreement, which Neipperg had plenipotentiary power to negotiate, the court in Vienna redoubled its quest for scapegoats. Both men were recalled and imprisoned, while a court of enquiry eventually drew up forty-nine charges against Wallis and thirty-one against Neipperg. The latter, by signing away Belgrade, had committed a crime with `no precedent in history’. Both men looked likely to suffer the same fate as Doxat, but they were saved by the unexpected death of Emperor Charles VI in October 1740. His twenty-three-year-old daughter, the Archduchess of Austria, Maria Theresa, wanted to bring an end to the whole catastrophe, so she closed down all the investigations and pardoned those who had been punished. She restored their ranks and privileges, and even made up their lost pay.