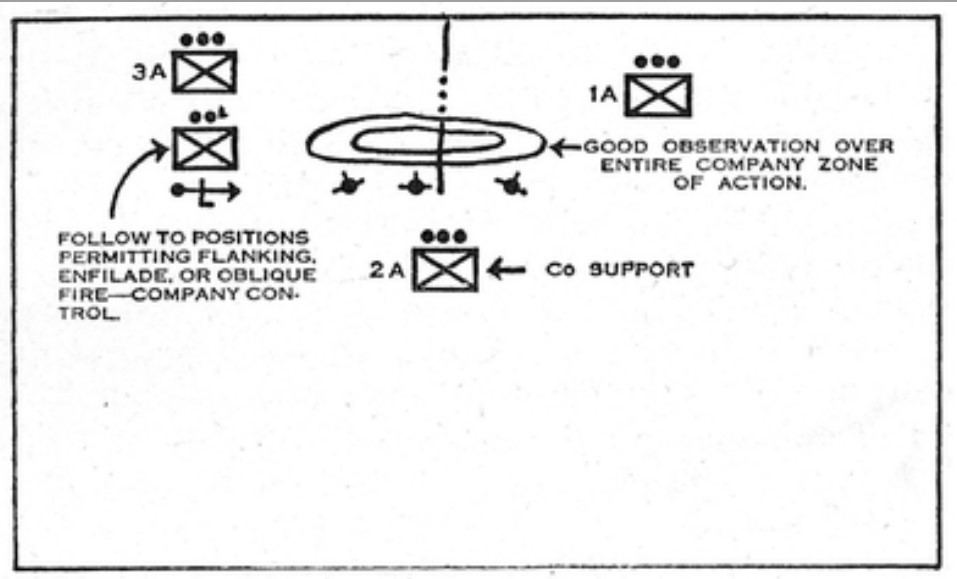

Initial dispositions of platoons for a ‘strong attack’, with the majority of the company forward. This could be developed into an enveloping attack if circumstances allowed. From FM 7-10 Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment, 1944.

Possible arrangements of squads during the approach march from FM 7-10 Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment, 1944.

From mid-1942 the US infantry manuals were comprehensively updated with the appearance of FM 7-10 Rifle Company, Rifle Regiment in June, and a new Rifle Battalion that September. Arguably, the new company manual was significant in that it appeared to suggest greater responsibility at lower levels of command, and that companies might themselves have greater combat significance than had been imagined before December 1941. For whilst the company acted in accordance with the battalion commander’s plan and mission, and was likely to be assigned either to the battalion ‘forward echelon’ or the ‘battalion reserve’, many of the smaller decisions could fall to the company commander. This was especially true when the company was detached,

When the company is acting alone, it is employed as directed by the commander who assigned the company its mission. The company commander will, of necessity, have to make more decisions on his own initiative than he will when operating with his battalion. His major decisions, as well as frequent reports of location and progress, are submitted promptly to the higher commander.

As a matter of course the company commander was responsible for administration, discipline, supply, training and control of his company: but Rifle Company also made it clear that he had an important tactical role. He was to anticipate and plan for prospective missions, supervise his subordinates, and decide on a course of action ‘in conformity with orders from higher authority’. This required a good ‘estimate of situation’ before the issuing of clear orders,

Having decided upon a detailed plan of action to carry out an assigned mission, the company commander must assign specific missions to his subordinate units. Company orders are usually issued orally to the leaders concerned or as oral or written messages. Sketches are furnished when practicable. Prior to combat, subordinates frequently can be assembled to receive the order. This facilitates orientation prior to the issuance of orders and enables the company commander to ensure that orders are understood…. Whenever practicable, the order is issued at a point from which terrain features of importance to subordinates can be pointed out. In attack, this often will be impracticable because of hostile observation and fires. If time is limited and leaders are separated, the company commander will issue his orders in fragmentary form. Leaders of units which are engaged with the enemy will not be called away from their units for the purpose of receiving orders.

Once combat was joined the company commander’s job became complex indeed. He was expected to know where the enemy was, and was capable of doing; keep track of both front and flanks, ensuring ‘all-round protection’; anticipate the needs of his platoons for supporting fire, and ensure that the sub-units supported one another; and check that his orders were carried out, whilst controlling company transportation and ammunition resupply. Nevertheless, he was still expected to find time to make ‘frequent reports’ to the battalion commander. Crucial to the performance of these tasks was the ‘Command Group’, comprising a second in command, first sergeant, communications sergeant, bugler, messengers, and orderly. The second in command, usually a first lieutenant, was expected to keep abreast,

of the tactical situation as it affects the company, replaces the company commander should the latter become a casualty, and performs any other duty assigned him by the company commander. During combat, he is in charge of the command post until he assumes command of the company, or of a platoon. He maintains communication with the company and battalion commanders. He notifies the battalion commander of changes in location of the command post.

The first sergeant usually assisted the second in command, and in combat might take responsibility for aspects of administration and supply, though in extremis he was used as a platoon commander, or as a substitute taking charge of the command post in case of casualties.

The communications sergeant naturally took charge of all aspects of communications, as well as assisting in preparation of sketches. Though often unsung, the duties of the communication sergeants were crucial, and when well performed could give the US infantry an advantage over both friend and foe as US units were usually better equipped in this department. The SCR 300 (‘Signal Corps Radio’) was a conventional-looking 32lb backpack model, giving a range of about 5 miles and was used between company and battalion. It could be operated by one man, but also be carried by one person whilst a handset was used by another. The little SCR 536 ‘handy talkie’ eventually issued down to platoon level was a genuine innovation. First produced in 1941, it weighed only 5lb, had an integral antenna, and a battery life of about a day in normal use. The whole set was held up to the ear and the operator depressed a switch to talk and released it whilst receiving. Though the range of the SCR 536 was less than a mile over some types of terrain, this was often adequate to bridge the gaps between company and platoons. Often at lower tactical levels voice-to-voice communications were used ‘in the clear’ and with no scrambling and only modest use of codes. It was reasoned, probably correctly, that in fast-moving situations swift delivery of accurate information was more important than a high level of security. In any event, when sets were first captured by the Germans in Sicily they were very impressed with them. Taking no chances, Rifle Company, 1942 also prescribes that as soon as a company is deployed each platoon should have a messenger report to company HQ.

In offensive situations it was expected that until the company left the route of march many decisions would be taken at higher levels, but as soon as deployment took place, or the unit was endangered, or under fire, the company commander would have responsibility. His orders, often issued in ‘fragmentary’ form due to pressures of time, would inform the platoons of known dispositions of both enemy and friendly troops; mission, objectives, and directions of march, including landmarks; frontage and reconnaissance requirements, and what actions to take in the event of being attacked. Where his company acted as part of a larger movement his ‘base’ platoon would act in conformity with that of the company designated as ‘base’ company within the battalion. Usually the company commander’s position would be at the front, and he was encouraged to make ‘personal reconnaissance’, but not attempt to tell his platoon commanders what precise formations and dispositions to adopt, unless what they were already doing disagreed with overall objectives and mission. In open terrain it was perfectly acceptable for platoons to be anything up to about 300yd apart so as to make best use of any cover or vantage points, but in close terrain, and especially woods, the platoons were to close up sufficiently that they were in visual contact.

The drill on contact was that only the element under fire would engage where they were – other platoons, and any squads not engaged, attempted to continue toward the objective, taking ‘every advantage of concealment and cover and assuring security of their flanks’ as they did so. By this method and ‘fire and movement’ they worked round the enemy and thereby assisted those held up. Where attacks on specific points were pre-planned the platoon commander had several options; perhaps holding back a part as a ‘manoeuvring element’, or sending forward a few riflemen aided by a BAR able to creep forward under cover and engage the enemy by surprise in a manner impossible for the whole platoon.

In any event, the platoon commander followed his attacking echelon closely, so as to be able to observe and direct his men.

When the platoon comes under effective small arms fire, further advance is usually by fire and movement. The enemy is pinned to the ground by frontal (and flanking) fire, under which other elements of the platoon manoeuvre forward, using all available cover to protect themselves against hostile fire. In turn, the original manoeuvring elements may occupy firing positions and cover the advance of the elements initially firing. The platoon leader hits the weak spot in the enemy position by having his support attack against the point of least resistance, or by manoeuvring his support around a flank to strike the enemy with surprise fire on his flank or rear . . . When fire from other hostile positions situated to the flank or rear makes it impossible to launch a flanking attack against a particular area, an assaulting force is built up by infiltration close to the hostile resistance. This force is protected by the fire of the rest of the platoon and of supporting weapons. One or more automatic rifles may be employed to neutralize the fires of the hostile flank or rear elements.

Having achieved a final jumping off point close to the enemy, this being defined as being as close as the troops were able to get without masking their supporting fire, the assault could begin. Though this might be a ‘general assault’ ordered by a company or battalion commander, it was equally likely to be started ‘in the heat of battle’ on the initiative of a squad, or even ‘a few individuals’. Any such attack warranted the immediate co-operation of every individual or unit within sight. Whilst platoon commanders would give the signal to stop supporting fire as his men crossed the last few yards, the attackers were to ‘assault fire’ during their final progress, bayonets fixed. At this crucial moment they would take ‘full advantage of existing cover such as tanks, boulders, trees, walls and mounds, advance rapidly toward the enemy and fire as they advance at areas known or believed to be occupied’.

Gung-ho as this may sound, the battle of what one Free French commentator in Italy called the ‘last hundred metres’ was often illusive, a fugitive beast, rarely seen, and less often caught on camera. Not infrequently men were nerved for final assault only to find that the enemy had already fled, or were, more or less successfully, attempting to surrender. The empty battlefield was so for a reason, as to linger was to invite death. As a US observer, also in Italy, described,

One never saw masses of men assaulting the enemy. What one observed, in apparently unrelated patches, was small, loose bodies of men moving down narrow defiles or over steep inclines, going methodically from position to position between long halts and the only continuous factor was the roaring and crackling of the big guns. One felt baffled at the unreality of it all. Unseen groups of men were fighting other men that they rarely saw.

What actually happened at such decisive moments in the infantry battle was analysed by Major GS Johns of US 29th Division in Normandy. First a machine gun might be knocked out. A man or two was killed or wounded, then:

Eventually the leader of the stronger force, usually the attackers, may decide that he has weakened his opponents enough to warrant a large concerted assault, preceded by a concentration of all the mortar and artillery support he can get. Or the leader of the weaker force may see that he will be overwhelmed by such an attack and pull back to another position in his rear. Thus goes the battle – a rush, a pause, some creeping, a few isolated shots here and there, some artillery fire, some mortars, some smoke, more creeping, another pause, dead silence, more firing, a great concentration of fire followed by a concerted rush. Then the whole process starts all over again.

Useful as it was, the advice of the 1942 manual was not given in isolation, nor was it regarded as the final word. In addition to two formal amendments, Infantry School offered a series of pictorial supplements, intended not only to keep the subject fresh and up to date but to present what might otherwise be dry and dense material in a fashion accessible to the NCO. Training Bulletin GT-20 of March 1943 for example expanded specifically on the subject of the approach march. By means of cartoon-style sketches, a simplified text, and tactical diagrams it showed exactly how the squad and platoon were expected to look, lined up for inspection, and in a series of tactical situations. Pictures showed how useful the informal platoon column was in moving through woods, fog, smoke or darkness, narrow spaces, and artillery fire, but also how dangerous it could prove if exposed to fire from the front. Also explained were the ideas of the ‘base squad’, tactical movement, and scouting. Platoon formations such as line of squads, and dispositions with one squad forward and two back – or vice versa – were similarly illustrated. As the Training Bulletin was issued on a scale of one per platoon it would appear to have been intended to reach platoon commanders and sergeants, and through them – probably verbally, their men.

The final US statement on small-unit infantry tactics prior to D-Day was the deservedly well renowned March 1944 edition of Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment. A solid 300 pages, this managed to incorporate the minutiae of several previous field manuals with some of the handy pictorial references of Training Bulletin. It encapsulated, so far as they were required for infantry, diagrams of the field works pioneered by the Protective Measures and Field Engineering manuals. Updated information was also given on the role and issue of individual weapons within platoons. Rifle grenade launchers were now widely distributed, ideally three per squad, plus one each to communication sergeants, platoon guides, squad and section leaders in light machine-gun squads, and even to truck drivers. Carbine launchers were also on hand, with one specifically allotted to the company bugler. Launchers were used for both the anti-tank grenade and, by means of an adaptor, the anti-personnel Mark II type. Hand grenades were described as being ‘especially useful’ against weapon crews or other small groups where they were located in places inaccessible to rifle fire, but inside the minimum range of high-angle rifle grenade fire.

For basic fire and movement the squad was regarded as three teams ‘Able’ which was the two scouts; ‘Baker’ comprising four men with the BAR; and the ‘Charlie’ five-man manoeuvre and assault team. The leader initially attached himself to the scouts. Where casualties intervened it was actually often the practice to make do with two teams, the smaller having the BAR. When one team was moving another was the ‘foot on the ground’, much as on the British model. Yet fire was also seen as antidote to many an adverse situation. As George S Patton put it,

The proper way to advance, particularly for troops armed with that magnificent weapon the M-1 rifle, is to utilise marching fire and keep moving. This fire can be delivered from the shoulder, but it can be just as effective if delivered with the butt of the rifle half way between belt and the armpit. One round should be fired every two or three paces. The whistle of the bullets, the scream of the ricochet, and the dust, twigs and branches which are knocked from the ground and the trees have such an effect on the enemy that his small arms fire becomes negligible.

Raids received more detailed treatment than before. Rifle companies were most likely to be committed, day or night, in ‘supported raids’. Ordered by battalion commanders who set the mission, time, and objective, these depended on both the element of surprise and the fire of supporting weapons. Details, however, were left to the company commander, who was usually given discretion regarding training, equipment, and conduct of the raid. His course of action would be informed by a preliminary reconnaissance. Important decisions included the designation of leaders and objectives for each party, and how to deploy the weapons platoon. Given that raids would not generally require heavy weapons to displace forwards, possible options included using its elements to protect flanks, assist in covering the withdrawal, reinforcing support fires, or provide men to carry captured materials or guard prisoners.

Company commanders were also well advised to keep in hand a support party, including rocket launchers, to use against unexpected enemy resistance or counter attack. This was particularly necessary since positions left vacant during the day might well be occupied by enemy reserves at night. Indeed, US instructions on night deployment specifically recommended that platoons close up tighter to each other at night, as this enabled them to keep in touch and reduced the possibility for infiltration under darkness. If a raid proceeded without preparatory fire by support weapons, the company commander had to be particularly careful to plan the timing of ‘protective fires’ by means of which objectives could be ‘boxed in’. Premature shooting roused the enemy, late firing might mean enemy units adjacent joining in the fray. Daylight raids were almost always ‘supported’.

‘Infiltration’, already mentioned in earlier manuals, was further elaborated in Rifle Company, 1944. Not an easy technique to achieve successfully it was defined as, ‘a method of advancing unobserved into areas which are under hostile control or observation. It requires decentralization of control; it means giving a unit, small group, or even an individual soldier a mission to accomplish, unaided. Upon the success of this mission often depends the success of larger actions.’ Infiltrations might be accomplished under any condition of ‘limited visibility’, as for example darkness, fog, heavy rain, very rugged terrain, or undergrowth. How many troops were committed to infiltration depended on the mission: small patrols of two or three might be all that was required for information gathering, anything up to an entire company might make an attempt if the objective was to launch an attack against the rear of a hostile position. In any case, secrecy was crucial, both to success of the mission, and the extraction of any who objectives required that they be returned unseen. In many instances security was better maintained under cover of distractions or ruses such as firing, racing engines, pyrotechnics, or movement of other units.

Extremely useful were infiltrations in conjunction with a co-ordinated attack, and in such tactics the infiltrating unit might be tasked to launch an assault against the enemy rear, single out command, communication, or supply facilities. Ideally, if the main attack was by daylight the infiltrators should complete their movement under darkness at least half an hour before dawn. Infiltrating bodies and those working with them needed careful preparation, as for example an initial assembly area within friendly lines, instructions on passing through friendly outposts, gaps in fronts and information drawn from prior reconnaissance. Standard practice was to have guides leading the infiltrating body to their departure point, and where possible guides into and through the enemy position chosen from previous patrols. Scouts and patrols could usefully screen and protect movement. The main body of an infiltration team moved in column, dispersed as the unit commander saw fit, but with any heavy weapons having to be carried by hand, preferably toward the centre of the column. Speed of movement would necessarily depend on circumstances such as visibility, terrain, and enemy activity, but with infiltration secrecy was more important than haste and allowances had to be made that enemy patrols might appear and cause delays. With this in mind, radios and pyrotechnics were not to be used during an infiltration but men were to have silent weapons to hand such as trench knives, small axes, ‘blackjacks’, and clubs.

Small groups could also perform useful infiltrations during larger attacks or in defence,

When the attack is slowed down or stopped, or when the attack is endangered, infiltrating elements may be able to work their way into enemy controlled terrain to cause confusion, give the impression of an attack from a different direction, disrupt communications or supply, or in other ways confuse or harass the enemy. They may move around organised localities and threaten them from the rear. These elements may consist of two or three individuals, or of entire squads.

It followed that units also had to be vigilant against the possibility of enemy infiltration, with observers covering open ground, and ‘roving combat patrols’ in places that could not be overlooked. Night patrols and ‘listening posts’ might substitute for conventional techniques after dark.

As before, the lighter weight Infantry School illustrated Training Bulletins supplemented the main manual. That of 30 June 1944 dealt with ‘security missions’, and was, in effect, a punchy aide-memoir against being taken unawares, it being ‘inexcusable for a commander to be surprised by the enemy’. The Training Bulletin therefore included not only pictorial refreshers on outposts, advanced, flank and rear guards, and the duties of the ‘point’ during the advance, but handy tips on civilians and sentries. The possibility that civilians might be something other than refugees or innocents was addressed by injunctions on preventing them preceding an advanced guard and prohibiting them from passing through outposts. In the event of encountering large numbers of refugees it was expected that ‘higher authority’ would issue orders on ‘collection and subsequent disposal’.

Given the special conditions encountered in the close bocage of Normandy such reminders were timely indeed. As Lawrence Nickell of 5th US Division recorded, the countryside here was cut into tiny parcels by old walls and hedges,

They were stone walls erected hundreds of years ago as the rocky fields of Normandy were cleared for cultivation. Over the years they had become overgrown with vines, trees had grown up on them and they were often three or more feet in thickness and six feet or more high. The Germans dug deep, standing depth foxholes behind the hedgerows and punched holes in the base of the hedgerows to permit a good field of fire for the machine guns they relied on so heavily.

Multiplied hundreds of times this became a whole new system of defence requiring new methods of attack, as was made clear by a 1st Army report,

In effect, hedgerows subdivide the terrain into small rectangular compartments which favour the defense. With careful organisation each compartment can be developed into a formidable obstacle to the advance of attacking infantry. By tying in adjacent compartments to provide mutual support a more or less continuous band of strongpoints may be developed across the front. Handicapped by lack of observation, difficulty in maintaining direction, and inability to use all supporting weapons to their maximum advantage the attacker is forced to adopt a form of jungle or Indian fighting in which the individual soldier plays a dominant part. The most effective attack proved to be by the combined action of infantry, artillery and tanks with some of the tanks equipped with dozer blades or large steel teeth in front to punch holes through the hedgerows. It was found necessary to assign frontages according to specific fields and hedgerows instead of by yardage and to reduce the distances and intervals between tactical formations. Normal rifle company formation was a box formation with two assault platoons in the lead followed by the support platoon and the weapons platoon.

Often the link between arms of service had to be closer still. Reports of the US 90th Infantry Division for example mention the motto ‘one field, one squad, one tank’. On approaching the enclosure the tank broke through into the field first, under cover of the infantry weapons. Inside it took position to cover the foot soldiers who advanced along the field edges. After initial heavy going the 29th under Major General Gerhardt adopted, and may even have initiated, much the same tactic, going so far as to practise and demonstrate the method at the divisional training centre at Couvains. On occasion the relationship of armour and infantry was reversed so that an infantry battalion was attached to a tank battalion for local security and ground holding. For bigger attacks the new Infantry Battalion manual of 1944 prescribed careful thought as to whether one arm should precede the other into action, or whether in the face of a well-prepared enemy ‘composite waves’ of tanks and infantry, following hard on indirect artillery and direct support fire, was the most flexible option.

Though Normandy was rightly regarded with huge mistrust as a hotbed of enemy snipers, and frequently trees and hedges were riddled by BAR men on the least suspicion of enemy activity, 1944 also saw the ultimate fruition of US techniques with the publication of FM 21-75 Scouting, Patrolling, and Sniping. As this appeared as early as February there was certainly opportunity for it to be seen, if not exhaustively practised, by the time of Overlord. As in earlier British summaries, the link between intelligence gathering, and the arts of stealthy movement, patrols, and sniping was seen as crucial. It brought together many of the earlier summaries of fieldcraft, stressing individual concealment, the need to remain motionless, and the value of observing and shooting through, rather than over cover. ‘Cover’ itself was now differentiated as a matter of course from ‘concealment’: the former protected against hostile weapons, the latter only against observation.

Whilst various forms of diamond arrangement for patrols of 8, 9, 12 or larger numbers were outlined, US patrolling formations were now regarded as ‘fluid and flexible’ with individuals taking their cue from the patrol leader and having regard to their ability to see each other whilst making ‘full use of cover and concealment’. Patrols could indeed change shape as they proceeded, and there was a general intention that should a patrol be fired upon the minimum number would be ‘pinned down’ by the enemy intervention:

Within a designated formation, points and flank groups move in and out as required in order to observe any cover for an enemy up to 100 yards, provided the inside man of the group can maintain visual contact with the patrol leader. Individual patrol members automatically move closer together in thick cover, fog, and at night; and farther apart in open terrain, clear weather, and in daylight. In general however, the lateral movement of flank groups is limited to 100 yards from the axis of advance.

Patrols were divided broadly into reconnaissance and combat missions. As in the British model, the former were the minimum size to achieve the objective, two or three men often being sufficient unless the excursion was expected to be protracted, or spares were needed as messengers. Reconnaissance patrols were not to indulge in combat unless for self protection or out of vital need to complete a mission, but specialists such as radio operators, mine technicians, or pioneers might be included as required. Examples requiring such special skills might include reconnaissance of mine fields, checking of friendly or enemy wire, or missions requiring rapid transmission of information to other units or HQs. Combat patrols could be both offensive and defensive. They might for example be required to screen a position, maintain a presence during darkness, or protect outposts, flanks, or important features and supply routes. Offensively they could be tasked for missions such as the capturing of prisoners or materiel, infiltration, destruction, or the interception of enemy patrols. Specific patrols were also mounted for sniper clearance.

US snipers were now defined as, ‘expert riflemen, well qualified in scouting, whose duty is to pick off key enemy personnel who expose themselves’. Eliminating enemy leaders and harassing the enemy by sniping softened enemy resistance and weakened morale. Snipers could be operated singly, in pairs, or small groups, and might be mobile or operate from stationary ‘observer-sniper posts’.

The mobile sniper acts alone, moves about frequently, and covers a large but not necessarily fixed area. He may be used to infiltrate enemy lines and seek out and destroy appropriate targets along enemy routes of supply and communication. It is essential that the mobile sniper hit his target with the first round fired. If the sniper is forced to fire several times, he discloses his position and also gives the enemy opportunity to escape. Therefore, although the mobile sniper must be an expert shot at all ranges he must be trained to stalk his target until he is close enough to insure that it will be eliminated with his first shot. Stationary observer-snipers: teams of two snipers may work together, operating sniping posts assigned definite sectors of fire. Each sniper is equipped with field glasses. His rifle has telescopic sights. One man acts as observer, designating the targets discovered to the firer and observing the results of fire. Using field glasses, the observer maintains a constant watch. Because this duty is tiring, it is necessary that the observer and sniper change duties every 15 to 20 minutes.

Sniper posts were chosen as good for concealment but offering excellent fields of fire. The exits from the post to the rear were to be well concealed, though covered approaches from flanks were avoided as far as possible. Actual firing points were not to be on skylines or against contrasting backgrounds, and so arranged that the muzzle of the rifle did not project obviously or dust was kicked up when a weapon fired. Snipers could not smoke in the post, and alternative posts were provided so that locations could be changed frequently. Individual snipers were usually armed with the sniper rifle, but for close country carbines might be chosen, and for missions behind enemy lines might carry other weapons such as a pistol or sub-machine gun. British sniper officer Clifford Shore considered the M1 Carbine the ideal mate to a telescoped rifle, with the second man firing the semi-automatic, as ‘for handiness mobility and ease of shooting this little carbine was certainly the finest weapon I ever handled’.

‘Several men’ per platoon were to be trained in the sniper role, though only one or two might actually be needed at any given time. The ideal candidates were already good shots with a sense of fieldcraft, and these were further trained in camouflage, navigation, silent movement, and made ‘physically agile and hardened, and able to sustain themselves for long periods of detachment from their units’. Contrary to popular belief, US snipers were not usually employed at very long ranges, nor did they constantly reset their telescopic sights to various ranges. Normally, sights were left set at 400yd and the sniper adjusted his own aim and sight picture automatically to compensate for distance, movement, and other factors. When the target was at 400yd and stationary the sniper aimed directly at the centre of mass, dropping his aim a foot for closer targets. For further objects he aimed higher, as for example at the top of an enemy’s head at 500yd. At 600yd the point of aim was 52in above the point to be hit, and much more than this was deemed impractical under normal battle conditions where targets were small or fleeting.