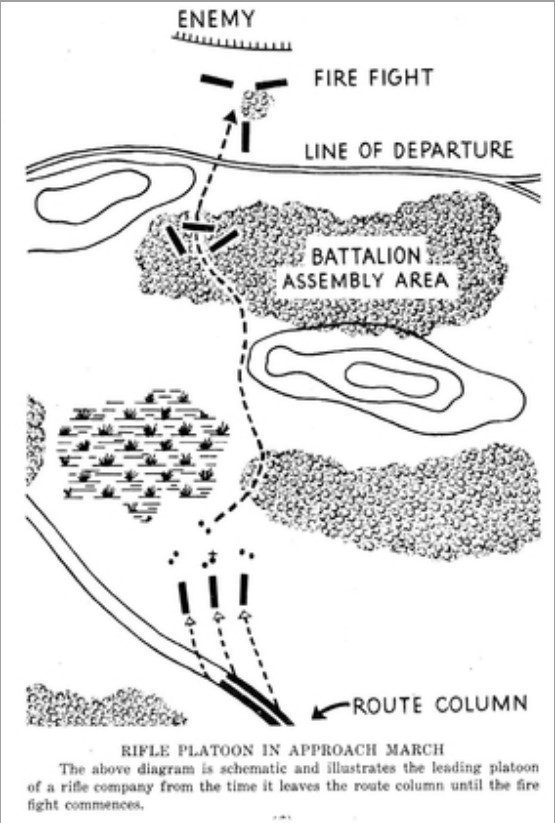

A typical sequence of events for the US rifle platoon as part of a battalion attack from the approach march. The platoon deploys from the road it has been using and advances in lose columns to the battalion assembly area. In co-ordination with the remainder of the battalion and the covering fire of artillery and other units it crosses the ‘line of departure’, arriving at the firefight with two of its three sections deployed in rough skirmish lines and the third in support. Taking advantage of cover, the enemy is now brought under effective fire until opportunity for close assault. From The Rifle Platoon and Squad in Offensive Combat, 1943.

The development of the foxhole, from squatting, to kneeling, and finally standing cover for the rifleman, as described in FM 21-45 Protective Measures, Individuals and Small Units, 1942.

The infantry was charged with ‘the principal mission in combat’ and decisive results were usually to be obtained by ‘offensive action’, though numbers, materiel, and other factors would often mean that defensive missions also had to be tackled. It was assumed that infantry units could overcome ‘improvised’ resistance, or ‘isolated hostile elements’ unaided, but that ‘co-ordinated continuing resistance’ would be likely to require the assistance of ‘powerful supporting weapons’ for successful outcome. Whilst the three-battalion regiment was the ‘complete tactical and administrative unit’, the rifle battalion was regarded as the ‘complete tactical unit’. It was capable of ‘assignment to a mission requiring the application of all the usual foot Infantry means of action’. All the weapons of the rifle battalion could be ‘manhandled over a distance of several hundred yards’.

The ‘approach march’ was defined as commencing once a battalion came within medium artillery range, or about 10 miles, of the enemy. In daylight it was then assumed that the advancing force would have to abandon ‘the route of march’ and adopt other formations, such as platoon single files or ‘column of twos’, going forward by ‘long bounds’ from one objective to the next. Dispersion did not need to be great where there was cover from fire or observation, and friendly formations in front, but units could cross dangerous areas ‘by infiltration’, gathering together again once an open space was crossed. Within the rifle platoons commanders nominated a ‘base squad’ to which the tactical deployments of the others conformed. By giving personal direction to the base squad the platoon commander could thereby effectively regulate the movement of the whole. Within companies it was usual for the rifle platoons to go first, followed by the weapons platoon. Commanders had to be suspicious of previously shelled areas or isolated features as these were likely to be pre-registered by the enemy and decide whether these should be skirted round or simply moved through as rapidly as possible. The ultimate objective of the approach march was to get the troops close to the enemy ready for action, but with minimum loss. The approach march was at an end as soon as the zone of effective small-arms fire was entered. For an attack of any scale, or had benefit of thorough preplanning, initial advances could be to designated ‘assembly areas’ in relatively safe spots that allowed units to reform before the assault.

When in proximity to the enemy leading rifle units progressed in extended order ‘reconnoitring so as to prevent elements other than patrols being taken by surprise fire by infantry weapons’. Designated reconnaissance teams were allowed freedom of movement, and encouraged maximum use of cover – as for example in crawling carefully to breaks in a skyline rather than wandering over a crest, remaining still to observe and check that no enemy overlooked the path, climbing trees, and keeping back from doors and windows of buildings. Wide detours were fully acceptable in avoiding open spaces or too close a proximity to an enemy post. For the close security of platoons two men per squad were also designated as ‘scouts’. These were more limited in that they were to move ‘boldly’ from cover to cover, usually within 500yd of their parent body. Often they were close enough to give visual signals, perhaps with one a little in front of the other so that the signal from the point could be relayed via his comrade back to the squad. Unlike reconnaissance teams, the main job of which was to collect information on the enemy and details of topography and equipment, platoon scouts performed their task more than adequately if they gave advance warning and prevented ambushes. In doing so they might well trigger enemy fire. As jaundiced squad scout Henri Atkins put it,

A point man needs a willingness to die. He is nothing more than a decoy. When he is shot, the enemy position is revealed. Don’t confuse this willingness with ‘bravery’. A point man is just doing his job, what he has been trained to do. Usually a scout is way out ahead of the attacking forces, ready to signal back enemy contact. He has a chance of survival, but not much of one.

According to Rifle Battalion, weapons were the ‘means of combat’, and the building block of all higher infantry formations was the squad – ‘the elementary combat unit’ – with a rifle squad being defined as a leader, second in command, and a minimum of five riflemen, ten at full strength. Three such squads, plus an automatic rifle squad of leader, second in command, six men, and two or three automatic rifles, made up the platoon. Three rifle platoons and a weapons platoon made up the rifle company. For general purposes, ‘short range’ was defined as anything up to 200yd; ‘close’ up to 400yd; ‘middle’ to 600yd; ‘long’ to 1,500yd; and ‘distant’ anything greater. Ideally, the frontage of a battalion was not more than 1,000yd; a company 500yd; a platoon 200yd; and the squad 75yd. Where wider frontages were required the practice was not to increase the distance between individual troops, but to leave gaps between the elements. An uneven distribution was perfectly acceptable, and could be turned to advantage by using such gaps for the flanking fire of machine guns. The preparation of the battalion-level attack was estimated to take a minimum of 1½ hours, commencing with the commander’s personal reconnaissance, followed by issuance of oral orders to a brief officer-group meeting, transmission of orders to all parts of the unit, and finally the advance.

In developing the attack it was expected that the commander would issue tasks to sub-units in terms of initial positions, directions of attack, zones of action, and objectives, but the smaller the unit the less detailed the instructions would be. A commander ‘prescribes a detailed tactical plan only so far as he can reasonably estimate the hostile resistance to be expected’. However, in attacks against co-ordinated resistance fire plans for support weapons were prepared,

When practicable, fires to dominate located resistance and neutralise areas from which hostile fire would be most dangerous are prearranged. Provision is made for engaging targets revealed during the course of the attack. Each unit seeks necessary augmentation of its own fire support by requesting that higher headquarters provide support from means under its control . . . In the absence of tanks, the fire of divisional artillery constitutes the basis of the fire plan of infantry regiments and battalions. The artillery neutralizes target areas in successive concentrations; it shells the nearer targets until the progress of the attack makes it necessary to transfer fire to a more distant zone. Fires are arranged in consultation with the commander of the supporting artillery.

It was a company commander’s job to ensure that supporting fires co-ordinated with the actions of the platoons ‘in place and in time’, perhaps by designating successive objectives and pushing in his light machine guns close behind the platoons. He was also to look for the ideal places to launch assaults, checking where resistance might be weakening. The infantry support weapons concentrated on targets too close for the artillery to hit safely, point targets revealed during the action, and ‘opportunity’ targets, though heavy machine guns could also be used to reinforce artillery by long-range fire. Mortars were placed as far forward as cover and ammunition supply permitted, with the 60mm type ‘within 400 yards of the front line’. In using them effectively observation was crucial. Light machine guns were used to fire through gaps in depth across the front of their own companies, or to flanks. Frontal fire was regarded as reserved for emergencies. Some weapons were held ready for rapid advance to positions for flanking fire. Others displaced forward as necessary.

The key offensive technique was ‘fire and movement’, and the closest possible co-ordination of the two was required so the infantry ‘may close with the enemy and break his resistance’. Indeed, as was explained in a passage that was but modest rephrasing of a passage from the book Infantry in Battle a few years previously, ‘Fire destroys or neutralizes the enemy and must be used to protect all movement in the presence of the enemy not masked by cover, darkness, fog or smoke. Through movement infantry places itself in positions which increase its destructive powers by decrease of range, by the development of convergent fires, and by flanking action’. Commonly, supporting weapons were well forward, allowing visual observation from emplacements: the infantrymen themselves were assumed to have highly destructive fire potential against ‘unsheltered personnel’ but against those under cover flat trajectory weapons were only of a neutralising effect. In moving sub-units were to take full advantage of broken or rolling terrain, avoiding whenever possible conspicuous or isolated features upon which the enemy might easily focus his fire. The very fact that progress against enemy concentrations was likely to be uneven could be used to advantage by taking flanks as they appeared, as for example by moving machine guns into new positions. As one terrain feature was occupied the advance to the next was organised – ‘fire bases’ being prepared for the next move. In close assaulting the enemy the best technique was to advance to the nearest available cover, then,

The assault of rifle units is usually initiated by units whose close approach has been favoured by the terrain or those which have encountered weak enemy resistance. A heavy burst of fire is delivered by all available weapons, following which the troops rush the hostile position. The assault of a unit is supported by every element in position to render resistance.

On arrival troops securing a lodgement in the enemy position were to turn their automatic weapons onto the flanks of any adjacent resistance, or upon retreating enemy. As far as possible, successful attacks were pushed right through the enemy lines, and the most advanced detachments ‘pushed forward without regard to the progress of units on their flanks’.

Details on tactical movement were filled in by the 1941 Soldier’s Handbook. Some of the advice was fairly obvious, as for example in lying flat and moving extremely cautiously when there was danger of being observed, or taking advantage of hedges, walls, and folds in the ground. However, a number of patrol formations and drills were also included, dependent on mission. ‘Security patrols’ for example might be used as advanced guards, rear guards, or flank patrols. Advanced and rear guards were likely to be disposed on both sides of a track or road, and ‘so arranged as best to let the leader control it, to make a poor target for enemy fire, and to permit all members to fire quickly to the front or either flank’. Such patrols were usually under standing orders to engage any enemy within effective fire range, and to send report of anything seen if they could not. Flank patrols could move alongside the route way at a given distance, or be concealed static protection. Extensive use of patrols was to be made in any direction where a flank might be exposed to the enemy. When in danger areas and until actually engaged, stealthy patrol movement was assumed, with for example streams being crossed one man at a time whilst others covered the ground. Reconnaissance patrols taken by surprise used a drill in which the first man to apprehend the threat called out the direction of the enemy. His comrades could then come to his aid on either side, and by doing so any small or isolated group of the enemy could be flanked. Wherever possible, patrol-squad leaders were encouraged to rush unprepared enemy individuals or small bodies. Night patrols required particular planning, and for these prearranged recognition signals were particularly vital.

Defensive infantry combat might take the form of ‘sustained defence’ or ‘delaying actions’ – these might be adopted deliberately, or be forced by the enemy. In sustained defence the usual infantry mission was to ‘stop the enemy by fire in front of the battle position, to repel his assault by close combat if he reaches it, and to eject him by counter attack in case he enters it’. As defending forces were likely to be weaker than attacking ones that had been concentrated for the purpose, defenders made maximum use of screening and concealment. Protection was not to be sought at the expense of disclosing dispositions as, ‘unmasked defensive positions will be promptly neutralised, if not destroyed, by superior hostile means of action’. Accordingly, the defence acted ‘by surprise’, varying its procedure and making every effort to keep the enemy in doubt about the main line of resistance and its principle elements. The enemy might be misled by camouflage, dummy works, screening by security detachments, and activity ahead of the main position. Whilst defenders relied heavily on fire, they were to remain ‘mobile and aggressive. Weak ‘holding elements’ at the front took advantage of the power of modern weapons to cover large areas and were reinforced by reserves shifted to meet the attacker with maximum strength and counter attacks.

Though main lines of resistance were often selected by higher authority, battalion and company commanders were to pick ‘detailed locations’ for smaller units taking particular account of observation and natural obstacles. Troops were to see, but not be seen, denying the enemy ability to view approaches to the position from the rear. Good communications in the rear were desirable to allow flow of men and materials to vital points. Sometimes reverse slopes would be adopted, with just small posts and machine guns on crests. Salients and re-entrants in the defensive position allowed for flanking fire from machine guns. Defenders were not to be distributed evenly, but to take maximum advantage of terrain and depth of positions and concentrate on key locations. Defending units might usefully be divided into three: the ‘security’ echelon; ‘combat’ echelon; and reserve.

‘Combat outposts’ on the German model formed the main element of security detachments beyond the main ‘battle position’. In larger defensive zones complete battalions could be given over to outpost duty together with artillery and anti-tank weapons. One outpost battalion might be given 2,000 to 2,500yd frontage to cover. Within the battle position itself were concentrated and co-ordinated all the resources required for ‘decisive action’, including a network of ‘fortified supporting points’ prepared for all-round defence. ‘Lines’ were to be avoided unless a defence was regarded as a ‘delaying action’ as a system based on holding successive lines was likely to result in dispersion of force. The ‘holding garrisons’ of points would consist of small groups usually built up around automatic weapons, positioned in depth and in ‘such a manner that the fires of each cross the front or flank of adjacent or advanced elements’. Unoccupied areas were covered by fire and counter attack. Frontages, though based on the ‘general’ figures already given, were varied according to terrain and situation, with narrower unit frontages and greater firepower devoted to vulnerable places where the enemy had benefit of covered approaches allowing them to get closer to the defenders. Conversely, obstacles allowed fewer troops to cover greater distances, and hence wider frontages for given units. Boundaries between units were not, however, to be on critical localities, as this would tend to divided responsibilities and confusion in event of attack.

Defensive fire was crucial,

The skeleton of the main line of resistance is constituted by machine guns and anti-tank weapons. Close defence of the position is largely based upon reciprocal flanking action of machine guns. The direction of fire of flanking defences often permits their concealment from direct observation of the enemy and their protection from frontal fire. They therefore have the advantage of being able to act with surprise effect in addition to that of protection and concealment. Frontal and flanking defences mutually supplement one another and subject the attacker to convergent fires. Gaps in the fire bands of machine guns are covered by artillery, mortars, automatic rifles and rifles. Riflemen and automatic riflemen furnish enough close protection for automatic weapons executing flanking fires and cover frontal sectors of fire. Premature fires from positions in the main line of resistance disclose the main defensive dispositions to the annihilating fire of the hostile artillery.

The best antidote to defending weapons being knocked out by enemy artillery was for them to wait until the enemy infantry got close enough that their supporting guns had to cease fire. At that point defenders could open fire on the attacking infantry, gaining surprise, and without fear that they would be hit in return.

The effectiveness of defensive fire positions could be much improved by the use of obstacles, such as wire, but they were not to be positioned in such a way as to telegraph the location of the main line of resistance. Wire could be disguised by being discontinuous, laid in vegetation, or put in stream beds. Where time allowed the protection of a position was progressively improved, not only by building up physical defences and digging trenches and bunkers, but by improving communications, stockpiling munitions, and protecting defenders against weather. Shell-proof shelters for reserves were regarded as a priority. Trenches were not, however, to be allowed to become conspicuous. Within battle position fire zones were adjusted so as to leave no gaps.

Though Rifle Battalion, 1940 was actually quite a good grounding for action at the time it was introduced, it was largely based on second-hand experience, and produced at a time of great change. As a ‘battalion’ instruction it was also not highly detailed on matters pertaining to squads. All these factors set limitations on its effective shelf life and scope. A number of other manuals and documents were, therefore, used as supplements or updates, especially where new weapons were introduced or new factors encountered. One of the most important of these was FM 21-45 Protective Measures, Individuals and Small Units, signed off by the Secretary of War at the end of 1941, and published in March 1942. This filled in many gaps, notably detail of concealment and cover, camouflage, digging of foxholes and trenches, awareness of booby traps, communications and information security, and protection against aircraft, chemical weapons, and tanks. It was intended to supersede the single chapter devoted to some of these aspects in the 1938 ‘Basic Field Manual’, which was by now pretty much out of date.

Significantly, Protective Measures acknowledged that modern war put a higher premium than ever upon ‘individual initiative’ and stressed both the role of the soldier and the ‘small group’, on whom rested ‘more and more’ the course of battle. It mattered little whether the task was bringing up a truck load of ammunition, preparing a meal, or outflanking a machine gun: if all these could be accomplished intelligently and unseen by the enemy every one of them would contribute to the probability of success and the ‘destruction of the enemy’. As if to emphasise how personal war could be, and the importance to the individual, Protective Measures and the latest soldier’s handbooks now spoke to the US private soldier in person. ‘You’ were told how to protect yourself and handle your weapons – – this was not some exercise in describing someone else in the third person, this was very much as though Uncle Sam was speaking direct to the citizen about his own responsibilities and the best way to stay alive whilst fulfilling them. Of course these manuals could be, and often were, used as teaching materials by others – and it is a fair guess that even the most conscientious and literate only dipped into them in places, but the message was clearer and more a matter of the individual knowing his job than ever before.

Interestingly, some of the material from Protective Measures did also appear in FM 21-100 Soldier’s Handbook of 1941, republished in a revised edition in March 1942. The information on camouflage and concealment was significant, but in many respects repeated that already found in German and British publications. The new material on ‘hasty entrenchments’ was arguably of greater interest, but was not the easiest to impart to reluctant soldiery for whom digging large holes was often not thought to be part of the job description,

In order to provide natural protection against hostile fire by hasty construction you must have a knowledge of the tools available, their use, and the types of hasty entrenchment which will afford cover. Permanent or semi permanent cover requires a long time and many men to construct, and will normally be done under the supervision of an officer. When your mission permits, you should provide or improve your cover by digging. You must know the various types of cover which you can provide and learn how best to construct them by digging them. These types have been developed by survivors of hostile attacks and tested under fire. It is hard work, and requires practice to dig them quickly and properly. Learn how before hostile action forces you to.

Many who did not learn how to dig quickly had indeed very short military careers: but some lazier GIs also found short cuts, for if the enemy had not thoughtfully ploughed up the ground with his weapons of war a small block of TNT purloined from the engineers might be made to fulfil the same function with gratifyingly little spadework.

Protective Measures divided up small-scale field works under the heads of skirmisher’s trench; foxholes; shell holes; slit trenches; shallow connecting trenches and squad positions. The skirmisher’s trench, which had in fact been taught during the First World War, was dug with the soldier prone, head towards the enemy. Naturally, it was best executed with proper digging implements, but under fire anything would suffice, as for example ‘your bayonet, mess kit cover, sticks or any other available object’. Lying on his left, the soldier first scraped a hole for head and body, then rolled into it. Then, lying on his right, excavated to his left enlarging the hole enough to get his head, shoulders and hips well down. Earth was thrown to the front so improving cover for the head and shoulders as quickly as possible. This accomplished the soldier then extended his scrape backwards enough to get his legs under cover.

In average soil you can get fair protection in about 10 minutes and finish the trench in less than an hour. The finished trench will give you protection against flat trajectory small arms fire but only partial protection against high explosive shell or bomb fragments. You should enlarge the forward portion into a foxhole as soon as enemy fire permits.

The foxhole was described as the ‘more usual form of hasty entrenchment’ and gave fair protection against bombs and shells as well as direct small-arms fire. It could be dug prone or crouching but was better made from standing when not under fire. It was dug progressively allowing squatting, kneeling, and finally standing fire positions as time allowed. With full-sized dedicated tools a standing foxhole could be completed in less than an hour, but with infantry implements in cramped conditions an hour and a half was considered more normal. In firm soil the lower portion of the hole could be enlarged to allow the occupant to curl up at the bottom, and so secure the best possible protection, even against tanks driving over. The last refinement was a sump at the bottom, ‘larger than a canteen cup’, to allow for bailing when the hole got wet. Shell holes were a good starting point for battlefield cover as much of the hard work was already done, and the enemy might not be able to distinguish which were being used as infantry cover.

Where a shell hole was purposely converted to best effect it was recommended that the soldier dig ‘2 or 3 feet into the forward slope to get a good firing position and lateral protection from shell fragments and enfilade fire’. Similar improvements could be speedily made to roadside ditches, banks, or other ready made features. In practice and with time it was found that two-man positions were often best, as a buddy allowed one soldier to rest and act as lookout during construction, or both worked together for maximum speed and encouragement. With the double foxhole, pair of holes, or converted shell hole complete it was now possible for one man to sleep whilst the other acted as sentry. In any event, morale was better and nasty surprises fewer with a second man in the hole. As the 1944 Infantry Anti Tank Company manual later explained, the two-man hole gave only slightly less protection, but was used when men needed to work in pairs, or ‘for psychological reasons, battlefield comradeship is desirable’. Once everyone in a unit had cover it was sometimes useful to link the individual positions using the ‘shallow connecting trench’. For creeping, crawling, and occasional use a depth of about 2ft was deemed adequate, though such slender cover was not ideal to fire from or occupy for protracted periods.

The slit trenches also had uses.

It gives excellent protection against all types of fire, air attack, and in firm soil, or when revetted in soft, provides protection against tanks passing overhead. It is excellent type of cover for the immediate protection of gun and vehicle crews and for anti tank lookouts. A slit trench is less visible to ground observation if it is dug parallel to the front and the spoil (dug out earth) scattered and concealed rather than used as a parapet. The cut sod should be saved and used for camouflage. Such a trench can be concealed by methods similar to those used in camouflage of a foxhole. A slit trench should be as narrow as possible and still admit you, and deep enough to permit you to get below the surface of the ground. A standing slit trench may be caved in by concentrated artillery fire. For this reason one dug in soft ground should be well braced and revetted. A single such trench should not be required to hold more than two individuals. When more are to be protected, dig more trenches. Slit trenches in the shape of a chevron or cross, about six feet on a side, will ensure enfilade protection against fire from tanks.

The basics of ‘squad positions’ were not hugely changed, but Protective Measures was far more detailed in its advice, perhaps more so than might be practical under many battle conditions. Ideally, the squad leader deployed each man personally with an eye to ‘all-round defence’. Every soldier was also allotted primary and secondary ‘sectors of fire’ – primary sectors usually being those areas fronting the squad in the direction of the enemy, whilst secondary sectors covered across the flanks to the frontages of adjacent squads at maximum distances of perhaps 200 to 400yd. Supplementary positions were also prepared to allow riflemen to shift to cover the flanks and rear of the squad position.

Fox holes for each primary and supplementary position are started as soon as possible after you deploy your squad and more fully developed as time and situation permit. Individual fox holes should be about five yards apart or they may be placed in pairs. If the position is to be held for some time, have the fox holes connected where necessary by shallow connecting trenches. If your men are to occupy the holes overnight, have them extend the fox holes on each side or deepen the connecting trenches so they can lie prone while sleeping . . . If an automatic weapon, automatic rifle, machine gun or submachine gun is available you should site it in an advanced position near the centre of your group of fox holes so that its fire can cover the entire sector of your squad and adjacent squads. Select an alternative position nearby to which it can move, if necessary, and deliver the same fire. Select a secondary position to permit its fire to cover to the rear.