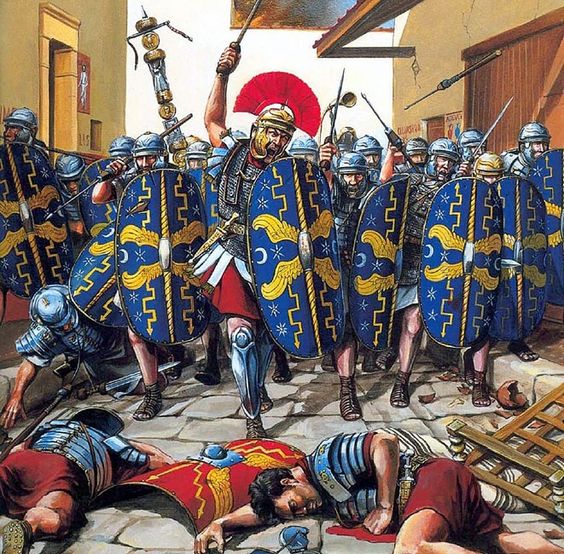

Praetorian Guard at the First Battle of Bedriacum or Cremona, 69 AD

Map of the Roman Empire during 69AD, the Year of the Four Emperors. Coloured areas indicate provinces loyal to one of four warring generals. The Battle of Bedriacum refers to two battles fought during the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE) near the village of Bedriacum (now Calvatone), about 35 kilometers (22 mi) from the town of Cremona in northern Italy. The fighting in fact took place between Bedriacum and Cremona, and the battles are sometimes called “First Cremona” and “Second Cremona”.

It was a cheap and ugly death that had overtaken Galba, the emperor, to be cruelly murdered by one of his own soldiers. Perhaps he would have avoided that if he had adopted Otho instead of Piso Licinianus. If he had done that, he may have lived a little longer to enjoy the power he had usurped.

On the other hand, perhaps not.

Military revolts almost always did fail, mainly for two reasons. First, all the Iulio-Claudians bar Nero had worked hard to build links with the soldiers independent of the chain of command. Soldiers received gifts on imperial accessions and anniversaries, gifts paid in good coin that often celebrated the military achievements of the Augustan family. A ruler who depended on military support could not afford to be indifferent, and sensible emperors made sure that they and those who featured in their dynastic plans visited camps and met the men. Take for instance the military revolt of Lucius Arruntius Camillus Scribonianus. When he tried to get the soldiers to march against Claudius the eagles could not be anointed with perfumed oils and dressed with floral garlands, and the standards resisted all efforts to remove them from their turf altars. The soldiers took it as an omen and backed down. For soldiers to go against an emperor, who was virtually a living god to them, was no easy matter by a long chalk.

The second obstacle was the fragmentation of the Roman élite, the only body from which any plausible successor could emerge. Empire wide at any one time there were some twenty-five senators commanding legions, and about as many governing provinces. Then from the ordo equester there were a clutch of governors of the smaller provinces, the commanders of the main fleets, the prefect of Egypt in Alexandria along with two praefecti legionum, and a few dozen procurators here and there. In Rome there were the rest of the senators, five hundred or so, and the commanders of the Praetorian Guards and of the cohortes urbanae. Staging a coup d’état meant forging some sort of consensus among all these. It did work out for Otho in Rome, but only at first and not elsewhere.

Marcus Salvius Otho was one of Nero’s closest friends and confidants, and as a member of the emperor’s inner circle this made him a powerful figure. But influence cannot be counted on to last for long, and Otho’s imperial favour wavered when the emperor took too strong a liking to his wife, the gorgeous but notorious Poppaea Sabina who was said to bathe in the milk of 500 donkeys, and the jilted husband was ‘banished’ to the remote Atlantic province of Lusitania to serve as its governor. This he did for ten years ‘with considerable moderation and restraint’.4 Out of revenge (and in hopes of great personal gains) Otho assisted Galba to become emperor.

When the elderly Galba, whose two sons had both died at a young age, adopted as his son and successor Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus, a long-named but a little-known scion of old Roman nobility – he was a descendant of those republican warlords Pompey and Crassus – a firm friend was turned into a mortal enemy. Although the Iulio-Claudians had used adoption, the idea that a successor might be selected on the basis of merit and not on the basis of his familial relationship to the emperor was a novel one. The thirty-one-year-old Piso Licinianus was highly acceptable to the Senate, enjoying as he did the considerable advantage of having been one of Nero’s victims, not, like Otho, one of his favourites. However, he was entirely unknown to the army and extremely inconvenient for others in the Galban camp. The scene was now set for the horrors of AD 69.

Friendship in these dark days is ironic at best, treacherous more commonly. The coal of resentment was perhaps burning brightly now, and so Otho decided to deal with Galba the biblical way: ‘No man, no problem.’ If Galba believed in omens, as he obviously did in prophecies, then the clearest sign of his impending downfall came on 15 January, the day of his death. While he was making a sacrifice on an altar before the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, the haruspex Umbricius, on examining the entrails of the victim, warned the emperor that danger was lurking and his liquidators were close by. Otho, by contrast, who was standing just behind Galba, interpreted this warning as a favourable omen. He felt sure of success when one of his freedmen came and informed him that the architect and the contractors were waiting for him. ‘It had been arranged thus to indicate that the soldiers were assembling, and that the preparations of the conspiracy were complete.’

Having turned to the praetorians, who happily proclaimed him emperor, Otho then had them remove Galba, along with the detested Piso Licinianus, who, for a brief five days, had been officially Servius Sulpicius Galba Caesar, son of Augustus. One cannot help but wonder, with the twilight of eternity closing down over his principate, if Galba recalled his own triumphant elevation and formal recognition all those months ago. Perhaps he felt a sudden cold certainty that this was how it had been meant to end, in a short and meaningless spate of violence, a fulfilment of a prophecy of the first emperor. For Augustus had once beckoned the young Galba to him, quizzed him on personal matters and finally conjured up a one-line horoscope in Greek: ‘You too will taste a little of my power, child.’9 And a little taste it was indeed. The Senate, in indecent haste, recognized Otho on the same day.

Otho’s claim to power depended partly on his association with Nero. In age and appearance, style and taste – even taste in women, we are told – he was closest to the man whom he had helped Galba to topple. In supplanting Galba, Otho revived causes that had been Nero’s. Otho was even billed as the ‘New Nero’ and ‘Otho Nero’, a desperate attempt to find popular support for his principate, which did initially work. The legions of the Danube took the oath of fidelity to Otho, as did those in Syria, Iudaea, Egypt and Roman North Africa. Fortune did not favour the new emperor, however, because, as Tacitus points out, law and order were in the hands of the soldiers who now named their own officers and demanded reforms, such as an end to the paying of bribes to centurions so as to escape menial tasks. Still, Otho’s biggest problem was the fact that his forces were scattered and he was immediately faced with Vitellius’ powerful provincial army (the seven Rhine legions having given him the imperial salutation), which was now marching rapidly on Rome. Though he had been the prime beneficiary of the toppling of his predecessor, he realized that it could be repeated to his cost. Otho therefore proposed a system of joint rule and was even willing to marry Vitellius’ daughter, or so said Suetonius. All this to no avail as we shall see, and besides, the Rhine tide could not be turned. Otho had no diplomatic cards left to play. For the emperor there was no other solution than to face his rival’s army.

On 14 March Otho left Rome and made camp at Bedriacum (now the village of Tornato), just north of the Po. On 14 April the decisive confrontation took place, in a neighbourhood dotted with vineyards somewhere between Bedriacum and Cremona. Badly outnumbered by that of Vitellius, Otho’s army was overcome, the restlessness of the praetorians being a factor in the result too. Vitellius’ generals had delivered on his behalf in open battle the knockout blow, and he travelled to Rome at his convenience. Deserted, Otho, having put his affairs in order and burnt all letters containing disparaging remarks about Vitellius, had taken his own life. He had been emperor for a little more than three months, dying ‘in the ninety-fifth day of his reign’.

Modern commentators, amateur and professional alike, have found one major problem with Otho’s campaign in the alluvial wetlands of the Po basin, namely its timetable. Galba fell on 15 January, but Otho did not quit Rome and head north until 14 March, the battle being fought one month later on the 14 April. Why did Otho start the campaign to save his principate so late? Was this a strategic blunder on the emperor’s part? Those who argue so are indulging in the second guessing that is so simple long after the event. Moreover, not only are they making too much of the luxury of hindsight, but they are also failing to consider three significant facts.

First, the Vitellian forces were certainly not expected to be in northern Italy by mid-April, the month the main Alpine passes were thawing. Unfortunately for Otho, the winter of AD 68/9 turned out to be an unusually mild one.

Second, the Othonians themselves were expecting to engage the Vitellian forces outside Italy and, as Tacitus says, ‘within the limits of Gaul’. Events would soon show how badly mistaken they were.

Third, Otho needed time to muster his army, particularly the four legions from Dalmatia and Pannonia.

This last point is more important than many a modern commentator will readily admit, but for myself, I shall make no bones about it. All Otho’s planning was frustrated by the Vitellian generals who led the invasion forces, Aulus Caecina Alienus, legate of legio IIII Macedonica, and Fabius Valens, legate of legio I Germania. Despite their faults, which seem to be many, they were both very able men who wasted no time in traversing the trouble-free Alpine passes much earlier than expected.19 Caecina Alienus even found the time en route to pick a quarrel with the Helvetii, many of whom, ill-armed and ill-trained, were either slaughtered or sold into slavery. But why did the Othonian legions seem slow to mobilize and march to join the emperor in Italy?

According to Tacitus the four legions of Dalmatia and Pannonia, ‘from each of which a vexillatio of 2,000 were sent on in advance’, exhibited ‘a tardiness of movement proportionate to their strength and solidity’. However, he does not provide us with any details on the progress of these Danube vexillationes marching to northern Italy. We do know that the vexillatio of legio XIII Gemina took part in a skirmish action prior to First Cremona, and that the whole legion fought at the battle itself, and the vexillatio of legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix actually made the battle but not its main body, which was ‘a few days away’. But what of the other three legions from Dalmatia and Pannonia, especially the one commanded by Marcus Antonius Primus? Of this matter concerning this particular legatus legionis more will be said later. The one legion from Dalmatia (XI Claudia pia fidelis) arrived far too late to participate in First Cremona, while the three legions from Moesia (III Gallica, VII Claudia pia fidelis, VIII Augusta) got no further than the town of Aquileia at the head of the Adriatic.

Otho wasted no time in vain regrets for what might have been, and it is now time for us to consider the background to the council of war called by the emperor, the issue at stake being to either fight immediately or hold back and delay. Tacitus only offers one side of the argument, that is to say, the case for delaying. Plutarch, on the other hand, presents both sides of the argument, the high moral of the Othonian army after the initial skirmish with the Vitellians having prompted many senior officers to push for an immediate decision there and then, and besides, they saw no sense in waiting for the Vitellian army to be reinforced.

Among Otho’s generals was Caius Suetonius Paulinus, onetime legate governor of Britannia and nemesis of Boudica. It was he who had defeated, along with Publius Marius Celsus, Caecina Alienus during a brush at a location Tacitus calls ad Castores. This was a small wayside shrine on the Via Postumia rather less than thirteen Roman miles east of Cremona, which was dedicated to Castor and Pollux of heavenly origin, Leda’s twin boys, eternally fixed in the ephemeral stardust. However, victory gained, Suetonius Paulinus would not allow his men to follow up their advantage and was consequently accused of treachery. As Tacitus reports, ‘it was very commonly said on both sides, that Caecina and his whole army might have been destroyed, had not Suetonius Paulinus given the signal of recall’. Worse still, in the eyes of his accusers, now that Fabius Valens had joined his forces with those of Caecina Alienus, Suetonius Paulinus was very much in favour of further caution, arguing that the Vitellian generals, unlike themselves, would have no more troops to hand. Moreover, he reasoned, it was preferable to wait for the summer, by which time the Vitellians would be tightening their belts for want of supplies.

Notwithstanding, Otho overruled the very experienced Suetonius Paulinus and made the decision to fight post-haste, with no reason being given. This may seem astonishing. But we must remember, it is far easier to recognize disaster the day after, than the day before. To know and understand the motives of another person is practically impossible even when those concerned live in daily contact with each other, and to evaluate correctly the motives behind the decision made by the emperor on this occasion is well-nigh impossible. Both Tacitus and Plutarch speculate upon why the scales were tipped in favour of immediate action, the latter authority reckoning the high moral of the praetorians, champing at the bit and thirsting for victory, prompted Otho to stake all on the lottery of battle. More telling, perhaps, is the fact that there was a move afoot, initiated by the senior officers of both sides, to seek a peaceful settlement, and certainly some of these trimming gentlemen were quite prepared to jettison one or both emperors, and even contemplated offering the throne once more to Verginius Rufus.

At the time Otho made his fateful decision one does not need to be possessed of an overly vivid imagination to appreciate that the emperor was probably rather anxious about the loyalty of his soldiers, not to mention some of his senior officers, and a sustained defensive stand along the Po could possibly see his army gradually melt away. All these thoughts must have run through the emperor’s head as he made up his mind. Besides, if Plutarch is to be believed, with the enthusiasm of the praetorians at fever pitch, these stalwart Othonians would have been in no mood for a long, uneventful defensive campaign. And, like a good general, Otho decided quickly enough that the best defence is attack.

Let a general assemble his men for action and lead them on to the battlefield. He may not be prepared outwardly to admit it, but in the pit of his stomach he will probably know exactly how they may be expected to perform. He knows how well or badly they have been drilled in the use of their weapons, and how quickly they can change formation as the action demands. He knows how fast they have marched to the field. He knows if and when they were last rewarded or worse, perhaps they have been existing on promises. At his back he can hear their muttered grumbles, he can smell their fear. And being human himself he is caught up in the general feeling within his army, be it one of outright determination or abject terror. His outward calmness will have a limited effect, but will it be enough?

When his men advance into mêlée, the chips are well and truly down. The enemy, who until now are a mere faceless mass, are about to become individuals. It is kill or be killed. So we are faced with the simple truth of it, the fact that until each general puts his force to the test he has only a slight idea as to the final outcome. Sleeting missiles and cold steel are only partial battle winners. The key to victory is morale.

There does not seem to be much point in delving minutely into the meaning of the word ‘morale’, most people nowadays having a very good appreciation of what it means but, just for the record, let me quickly say that, in military terms, it is the state of mind of a single soldier in particular or of a unit in general, with special reference to his or its enthusiasm, expertise, training, faith in the immediate command element, physical state, fatigue and a host of other relevant factors. Morale, a movable factor, varies as the battle ebbs and flows, as casualties mount, as the enemy breaks and runs, as the unit standard bearer is cut down and his beloved standard is carried away in triumph by his killer. What it really boils down to is the question of whether soldiers will carry out the mission assigned to them, no matter how fraught with difficulties it may be, or whether, as a result of unwillingness – in this particular event, are they willing to fight and die for Otho’s cause or are they pressed men with little stomach for the job? – their experience, especially in regard to the battle losses they may already have suffered, or their lack of confidence or training, causes them to be incapable of obeying orders and to shrink from the perils involved in achieving the objective they have been assigned.

While, of course, it is abundantly apparent that the better the training, the greater the length of service, and the more genuine their enthusiasm for the cause for which they are fighting, the more likely it is that soldiers will obey orders that are likely to put them in the greatest danger, this yardstick of obedience and behaviour does not always hold good and, while still within the framework of the possible, the unpredictable could and did happen. Which brings us nicely back to First Cremona.

We are pretty sure that the Vitellian army included V Alaudae and XXI Rapax, and strong vexillationes from all the other five Rhine legions. There was also I Italica, which had been picked up en route at Lugdunum, the provincial capital of Gallia Lugdunensis. The Othonian army included I Adiutrix and XIII Gemina, as well as a vexillatio from XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix, the praetorians, and a force of gladiators from Rome. On the day, Otho himself remained behind with a sizeable force of praetorians at Brixellum (Brescello). Tacitus rightly sees this as a grave mistake on Otho’s part, not only because it meant the absence of those detailed to protect the emperor, ‘but the spirit of those who remained was broken, for the men suspected their generals, and Otho, who alone had the confidence of the soldiers, while he himself trusted in none but them, had left the generals’ authority on a doubtful footing’.

Leaving a strong detachment to guard their camp at Bedriacum, thereby reducing their numbers yet again, the Othonians marched towards Cremona along the Via Postumia. A short distance from that town they unexpectedly encountered the Vitellians, the Othonians evidently tired after their long march. It was now that the men of I Adiutrix, the leading Othonian legion, got it into their heads that their Vitellian opponents had decided to desert to their side. The cheers and greetings of the Othonians were answered by fierce yells and abuse from the Vitellians. This inauspicious incident was doubly unfortunate for the Othonians. It convinced the Vitellians that they had no fight in them, and the bizarre behaviour of the greenhorn I Adiutrix created the uneasy feeling amongst its fellow formations that it meant to forsake them.

One does not have to be a student of military matters to be aware that, in warfare, terrain features, whether they be woods, rivers or hills, exercise a powerful influence on the conduct of operations and that the possession of a certain piece of real estate, elevated ground for example, can be of inestimable value to a military force, operating greatly to the detriment of an enemy army. So, without further ado, we should turn to the real physical setting of these events, a flat landscape crossed by two linear features, the river Po and the Via Postumia, though visibility and movement were restricted by the water ditches, poplar trees, fields of millet and barley and vineyards. Thus, like the two opposing armies in chess, one the mirror image of the other, the Vitellians and the Othonians glared at one another across a maze of vineyards and watercourses, which made up the small deadly space between them. All that remained now was them to rush together and get to grips in the massive vulgar brawl provided by hand-to-hand combat.

Some of the heaviest fighting was where I Adiutrix, recently raised from the Misenum marines and eager to gain its first triumph, and the veteran XXI Rapax clashed head to head. Despite their initial faux pas, the former marines acquitted themselves extremely well, even managing to overrun the front ranks of their opponents and capture their eagle. The eagle, aquila, was the totem animal of the legions, so to lose it was the ultimate disgrace for a legion, and XXI Rapax gathered itself and charged the attackers in turn, which showed that the resolution of this legion was still unbroken and betokened the discipline of veteran soldiery. The fighting was obviously vicious, the legate of I Adiutrix, Orfidius Benignus, fell fighting as the Vitellians strove to retrieve their sacred eagle. This they failed to do, but they did harvest a number of standards and flags.

Much earlier we asked the question if the tall, fit and superbly disciplined men of legio I Italica could fight. In the centre of the battlefield Nero’s handpicked legionaries came face to face with the Otho’s praetorians who, as we know, had been itching for battle. The two sides, equally determined, slogged it out hand-to-hand, throwing against each other the weight of their armoured bodies and bossed shields.35 Before contact, the usual discharge of pila had been discarded, and gladii and axes were used to puncture metal and man. We will have more to say about Roman fighting techniques in a little while.

At the other end of the Othonian battle line, however, XIII Gemina and the vexillatio from XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix were roundly defeated by V Alaudae.

Tacitus’ details are rather vague at this point, but it appears that XIII Gemina turned on its heels and fled at the sight of the charging V Alaudae. This left the heavily outnumbered vexillatio of XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix in the lurch, and consequently it ‘was surrounded by a superior force’, and presumably either annihilated or the survivors given quarter.

While these events were unfolding I Adiutrix met its own fate. Reeling from the loss of its legate, and presumably many of those around him, the legion eventually gave way when the Batavi, flushed with their thumping victory over the gladiators, took them in the flank. Earlier in the day Otho had ordered Flavius Sabinus to stage a diversionary attack from the south bank of the Po, and consequently he had loaded his gladiators onto boats supplied by the classis Ravennas. Having landed on the other side and ventured a ways from the riverbank, they were suddenly pounced upon by the Batavi under Alfenus Varus. Most of them made it back to the river only to be cut down by other Batavi positioned there to block their escape. So, with the right and left now gone, we can safely speculate that the praetorians in the centre threw in the towel and called it a day. The surviving Othonians fled back to their distant camp at Bedriacum, and the next day, with some reluctance it should be said, took the oath of allegiance to Vitellius. These are the bare bones of First Cremona.