In November 1944, German war production neared its peak. Satisfied with the speed of his Ardennes buildup, Hitler decided to make sure his offensive was not threatened by an American capture of Schmidt. He therefore reinforced Brandenberger and Schmidt with several new Volks artillery corps (equivalent to about a regiment of artillery) and Nebelwerfer (rocket launcher) brigades. He also temporarily assigned the 5th Panzer Army, under Gen. of Panzer Troops Hasso von Manteuffel, the task of defending the Stolberg Corridor and the sector east of Aachen to deceive the Allies into believing that it was already committed. Then the 5th Panzer was secretly with- drawn and sent south to assume its real mission: directing one of the two major drives into the Ardennes. Meanwhile, Gen. of Infantry Gustav-Adolf von Zangen’s 15th Army, temporarily dubbed Gruppe von Manteuffel, in accordance with the German deception plan, took charge of the northern wing of Brandenberger’s sector, including the LXXXI Corps in the Stolberg corridor and the northern tip of the Huertgen Forest. At the same time, Army Group B was reinforced with a new reserve: the XXXXVII Panzer Corps, with a tank and a panzer grenadier division. Model, who could not believe that the Americans intended to launch their main offensive in the Stolberg Corridor-Huertgen Forest sector, posted these divisions farther to the north on the Roer River plain.

The Allies’ November offensive against the Siegfried Line, dubbed Operation Queen, was a huge affair involving both the U. S. Ninth and First Armies, as well as the British XXX Corps on the northern flank-seventeen divisions in all. General Bradley said that it might be “the last offensive necessary to bring Germany to her knees,” and General Hodges expressed the same opinion in almost the same words. The main attack, which was launched by Collins’s VII Corps, began on November 16-the last possible date, according to Bradley’s timetable. It was proceeded by a carpet-bombing attack by more than 1,200 heavy bombers from the U. S. Eighth Air Force, which blasted the German assembly areas, field installations, and communications and supply lines, as well as the city of Eschweiler in the Stolberg Corridor and the town of Langerwehe in the northern tip of the Huertgen Forest. At the same time, more than 1,000 British bombers destroyed Dueren and other targets on or near the Roer River, while 600 medium bombers from the U. S. Ninth Air Force attacked smaller towns in the Stolberg Corridor. The ubiquitous fighter-bombers blasted the German front lines. In all, more than 4,500 airplanes took part in the attack, about half of them heavy bombers, and more than 10,000 tons of bombs fell on German positions and installations. It was the largest air attack in direct support of ground forces during the war.

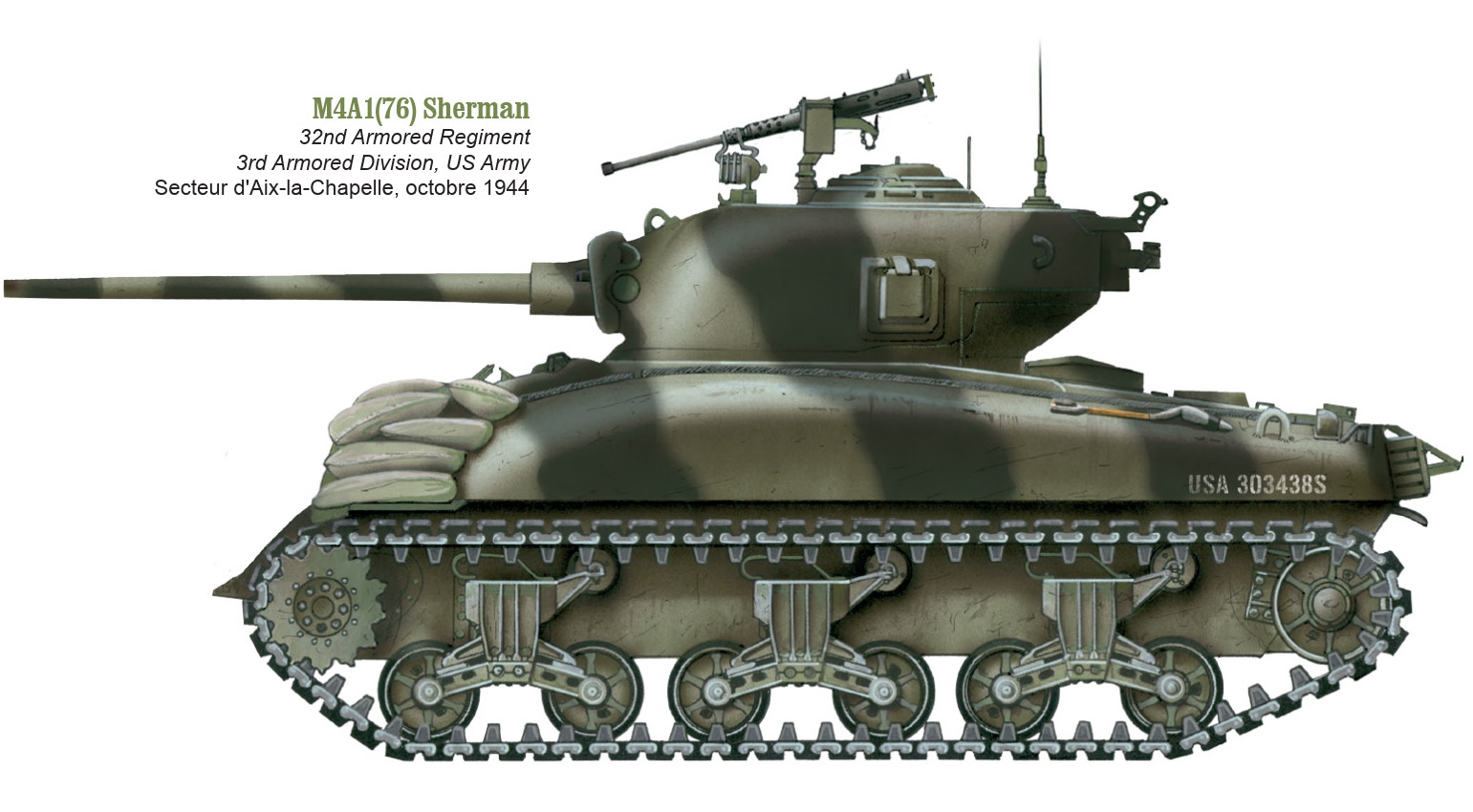

The air attack was followed by an artillery bombardment by 1,246 guns, and then the main attack, which was supported by more than 300 tanks and tank destroyers. For his attack, Collins controlled the U. S. 1st, 9th, and 4th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 3rd and 5th Armored Divisions. The 4th Infantry, reinforced by Combat Command Reserve of the 3rd Armored Divison, was committed to the Huertgen Forest with the objective of clearing it and capturing Dueren. The other divisions were to push through the Stolberg corridor to the Roer.

To defend against this massive offensive, General Koechling’s LXXXI Corps had, from north to south, the 246th Volksgrenadier Division; the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division; and the 12th Volksgrenadier Division. General Schmidt’s 275th Infantry Division, still part of the 7th Army, was also subjected to massive attacks in the Huertgen Forest.

The 246th Volksgrenadier, which was to face the attack of the U. S. Ninth Army, was the worst of the lot, although it had been partially rebuilt after Aachen, absorbing the survivors of the now-defunct 49th Division. Under the command of Col. Peter Koerte, it was organized like most Volksgrenadier divisions and consisted of three infantry regiments of two battalions each, an artillery regiment, an engineer battalion, and an assault gun (antitank) battalion. Because many of its troops were seventeen-year-olds with only six weeks of training, it was rated fourth class-suitable for limited defensive missions only-in spite of the fact that it now mustered 11,141 men.

The 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Walter Denkert, had about 11,000 men, many of them Volksdeutsche, and was a third-class unit-suitable for unlimited defensive missions. It consisted of two panzer grenadier regiments, the 8th and 29th; a motorized artillery regiment, the 3rd; and a tank battalion, the 103rd, equipped mainly with assault guns. It also controlled the 103rd Panzer Reconnaissance, 3rd Tank Destroyer, 3rd Motorized Engineer, and 3rd Motorized Signal Battalions.

In the Stolberg Corridor, opposite the main U. S. attack, was the 12th Volksgrenadier Division, which had a strength of 6,381 men. Even though it had lost more than half of its men since September, the 12th was still rated as second class-capable of limited offensive action-because of its high state of morale and training. It was well led by Gerhard Engel, Hitler’s former army adjutant, who had been promoted to major general on November 1. The units of the LXXXI Corps were supported by sixty-six 105-millimter and thirty-one 150- millimter howitzers, plus an assortment of thirty-one other guns, including 122-millimter Russian howitzers. They also had fifty-four assault guns, eleven 88-millimeter antitank guns, and forty-five anti-tank guns of small caliber.

In addition to these forces, Lt. Gen. Max Bork’s 47th Volksgrenadier Division was just arriving in the corps sector by train and beginning the process of relieving the 12th Volksgrenadier at the front. About half of its men were former Luftwaffe and naval personnel recently transferred to the infantry; most of the rest were seventeen- and eighteen-year-old boys who had been rushed to the front with only six weeks’ training. Although its equipment and weapons were good, most of the troops were unfamiliar with them; the artillerymen, for example, had only one week of training with their guns before they were sent to the front. The antitank weapons would not arrive until long after the 47th was sent into battle.

The unlucky 47th, much of which was just getting off the trains when the American offensive struck, took the worst of the bombardment. One artillery battalion at Juelich was almost completely wiped out along with the city. The signal battalion and General Headquarters units were devastated in Dueren, which was so badly damaged that it was said to resemble a Roman ruin. Some infantry units were also marching to the front when the Americans air attack began and were pulverized by medium bombers and fighter-bombers. “I never saw anything like it,” one German sergeant later told his American interrogator. “These kids . . . were still numb forty-five minutes after the bombardment. It was our luck that your ground troops did not attack us until the next day. I could not have done anything with those boys of mine that day.”

The 12th Volksgrenadier, however, was in much better shape. Contrary to Allied expectations, it was relatively unhurt by the bombardment. Engel’s frontline troops had been in their positions for some time, had burrowed deep into the German earth, and were protected by bunkers and pillboxes. Prisoners later estimated that the forward regiments suffered casualty rates of 1 to 3 percent. Their communications were completely disrupted, however, and they would be without hot food for days, because the bombardment had destroyed most of their field kitchens, supply vehicles, and horses. Despite being outnumbered five to one in infantry, Engel’s troops managed to hold Hamich on November 16 and 17 against repeated American attacks. One U. S. infantry battalion suffered 70 percent casualties before it withdrew. The town finally fell on November 18, but the U. S. 1st Infantry and 3rd Armored Divisions still had to face persistent counterattacks from the 48th Infantry and 12th Fusilier Regiments.

German reactions to the offensive were both slow and incorrect. Zangen’s 15th Army had taken over this sector only on November 15, but Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army Headquarters had not yet departed. These two capable generals set up an informal combined headquarters and directed the battle as a team until November 20, when Manteuffel left for the Ardennes. Zangen and Manteuffel tried to create an army reserve by combining what was left of the 47th Volksgrenadier Division with a small kampfgruppe from the 116th Panzer Division, but Field Marshal Model ordered this force to counterattack and retake Hamich, despite the objections of Zangen and Manteuffel. Model still believed that the main Allied offensive would come farther north, near the boundary of the XII SS Corps and LXXXI Corps-not in the southern sector of the LXXXI Corps and on the northern boundary of the 7th Army. Model therefore committed the local reserves too soon and did not reinforce the threatened sector with his main reserve force, Gen. of Panzer Troops Baron Heinrich von Luettwitz’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps.

Shortly after nightfall on November 18, the remnants of the green 47th Volksgrenadier Division formed up into two battle groups. At 5:30 A. M. the next morning, they attacked the U. S. 1st Infantry Division and pushed it back to the outskirts of Hamich but could not eject it from the village. By now, it was obvious that the great break- through was not going to occur and that Operation Queen was not going to bring Nazi Germany to its knees, as Omar Bradley and Courtney Hodges had hoped.

To the north, the British XXX Corps was also in trouble. Its objective was to pinch off the Geilenkirchen salient and then push on to the small Wurm River, capturing the fortified villages of Hoven, Wurm, Mullendorf, and Beek in the process. At first everything went well. The green U. S. 84th Infantry Division advanced one and a half miles and took the village of Prummen while the veteran British 43rd Infantry Division on the left flank advanced two and a half miles, completely encircling Geilenkirchen and elements of the 183rd Volksgrenadier Division. The XXX Corps resumed its drive in the predawn darkness of November 18, attacking the thick minefields in front of the West Wall. This attack was spearheaded by elements of the British 79th Armoured Division and illuminated by “Monty’s Moonlight”- powerful searchlights shining on the clouds, which reflected the light downward onto the battlefield. The 79th Armoured’s specially designed tanks cleared the mines by using chain flails, which extended two yards in front of the tanks, causing the mines to explode harmlessly. Using this ingenious method of attack, the British breached the minefields within two hours, and by noon, the 43rd Wessex Division had been committed to the battle, attacking the forward line of pillboxes in the Siegfried Line. Then the trouble began. The American-made Sherman tanks with their narrow tracks bogged down in the mud, but the Germans, profiting from their lessons in Russia, had no such problem. Both the British 43rd and U. S. 84th Divisions were soon counterattacked by Lt. Gen. Eberhard Rodt’s veteran 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. “It was galling to see their tanks with their broad tracks maneuvering over muddy fields impassable to our own,” Brig. Hubert Essame, the commander of the 43rd, recalled. The American attack bogged down in the Siegfried Line, but the 43rd Infantry pushed on as far as the Wurm in four days of heavy fighting. “Years after the event,” the historian of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry wrote,

those who survived could recall the intensity of the enemy fire and the sloppy ground over which they had to move to reach their objective. What is difficult to describe is the physical agony of the infantryman. . . . The November rain seemed piercingly cold. After exertion when the body warmed, the cold air and the wet seemed to penetrate the very marrow of the body so that the whole shook as with ague, and then after shaking would come a numbness of hand and leg and mind and a feeling of surrender to forces of nature far greater in strength than any enemy might impose.

On November 22, Horrocks, the commander of the XXX Corps, ordered one final effort, and the British spearhead, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI), attacked the village of Hoven. But they were met by a hail of fire from Harmel’s 10th SS Panzer Division, which Rundstedt had hurriedly brought down from Holland on November 16. “They went down everywhere, the muddy fields littered with crumpled dead,” historian Charles Whiting wrote later. Despite its heavy casualties, the men of DCLI pushed into Hoven but were soon virtually surrounded by the SS, who broke through into their rear. The U. S. 84th Infantry Division on the right flank tried to help but could not break through a German bunker line on the heights around the village of Suggerath, which the men of the tough 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had been ordered to hold at all costs.

Inside Hoven, the DCLI was smashed by the 10th SS Panzer. The town was leveled by the panzers, and two British companies were overrun. The entire battalion would probably have been destroyed had it not been for their PIATs, a spring-loaded form of the bazooka. The battle was so intense that the DCLI ran out of ammunition but fought on with weapons taken from dead Germans. The battalion commander was killed and both remaining majors were wounded, but still the light infantry struggled for survival. By now, the cellars were full of British and German wounded.

The battle continued until the next day, when the survivors of the DCLI broke out of the encirclement, led by their two wounded majors. One company had lost 105 of its 120 men. The northernmost thrust had been blunted. “The steam was going out of the whole huge . . . action,” a British historian wrote later.

Between the British XXX Corps and the U. S. First Army, the U. S. Ninth Army advanced across a relatively open plain dotted with villages and strongpoints. Although the terrain in this sector was much less formidable than that over which the First Army advanced, resistance was also stiffer because Model expected the main Allied offensive to come in this zone and had stationed some of his best units here. The defenders were all under the command of Zangen’s 15th Army and included Gen. of Infantry Guenther Blumentritt’s XII SS Corps, with Colonel Landau’s 176th Infantry Division, General Lange’s 183rd Volksgrenadier Division, the 388th Volks Artillery Corps, the 301st Panzer Battalion (thirty-one Tigers), and the 559th Assault Gun Bat- talion (twenty-one guns). Immediately behind the XII SS Corps lay Luettwitz’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps-Army Group B’s main reserve- with the 9th Panzer Division, elements of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, and the 506th Heavy Panzer Battalion (thirty-six Tigers).

On November 16, the first day of the offensive, the 2nd Armored Division of the U. S. XIX Corps practically annihilated the 330th Grenadier Regiment of the 183rd Volksgrenadier Division and pushed to the edge of Juelich but lost thirty-five tanks in the process-fourteen to mines, ten to assault guns, six to artillery fire, and one each to mortar fire, mud, panzerfausts, and mechanical failure. Another was lost to a combination of mines and antitank gunfire. Elsewhere, the XIX Corps gains were limited to about a mile. The next day, the 2nd Armored Division was counterattacked by Maj. Gen. Baron Harald von Elverfeldt’s 9th Panzer Division, and a real tank battle ensued. By the end of the day, at least eleven Panzers and Tigers had been knocked out, but the Americans had lost eighteen Shermans destroyed, sixteen damaged and out of action, and nineteen Stuart light tanks knocked out or destroyed. In the end, the 2nd Armored retreated and was relieved that the 9th Panzer did not follow.

On November 18, the U. S. 29th Infantry Division joined the fighting around Juelich, and the tide of battle began to turn in favor of the Americans. The 2nd Armored continued to fight indecisively with the 9th Panzer, but the 29th Infantry Division managed to push forward and, by the end of the day, had taken the villages of Siersdorf and Bettendorf from the 246th Volksgrenadier Division and had bro- ken the first defensive ring around Juelich. By nightfall on November 21, it had cracked the second ring and was within a mile and a half of the Roer, where it was checked. On November 22, Zangen commit- ted two regiments of Col. Theodor Tolsdorff’s fresh 340th Volksgrenadier Division-one at Linnich and the other at Juelich. The third regiment of the division was committed at Juelich the next day, and the American advance was halted, despite the arrival of the U. S. 30th Infantry Division. On November 23, the 9th Panzer Division was withdrawn from the battle and sent to the rear to rehabilitate for the Ardennes attack.

On November 26, General Koechling’s LXXXI Corps launched a major counterattack in the Juerlich sector, using two grenadier regiments of the 340th Volksgrenadier, the 301st Heavy Panzer Battalion, and the 341st Assault Gun Brigade, all supported by fourteen artillery battalions. Fortunately for the Americans, the German artillery was hamstrung by a shortage of ammunition, which was being horded for the Ardennes offensive. The Americans fired an estimated 27,500 rounds against the Germans and broke the back of the counterattack. They were still bogged down west of the river, however.

#

Everywhere the story was the same: unexpectedly stiff German resistance, unexpectedly high casualties, and no major breakthroughs anywhere. The story of Combat Command B of the U. S. 3rd Armored Division was fairly typical. Led by Brig. Gen. Truman E. Boudinot, it jumped off at H-Hour, 12:45 P. M., on November 16 between the U. S. 1st and 104th Infantry Divisions. It attacked in the Stolberg Corridor-excellent terrain for armor-with the objective of capturing four villages on the western edge of the Hamich Ridge. None of the four were more than two miles from the combat command’s front line when the offensive began. The 89th Grenadier Regiment of the 12th Volksgrenadier Division defended the villages. Once it had captured the four villages, CCB was to be relieved by infantry and was to return to its parent unit in reserve in order to prepare for the next phase of the operation, the pursuit.

Struggling through the mud, CCB took all four objectives in three days of heavy fighting, but its losses were prohibitive. The armored infantry suffered 50 percent casualties, and tank losses were worse. Of the sixty-four medium tanks available at the start of the operation, only twenty-two were still operational when it concluded. Seven light tanks had also been knocked out, for a total loss of forty-nine tanks. Of these, German antitank fire had claimed twenty-four, panzerfausts had knocked out six, artillery fire had destroyed six, mines accounted for twelve, and an American airplane mistakenly attacked one. “These did not look much like statistics of a breakthrough operation,” the U. S. official history noted later. Certainly, CCB was no longer in any shape to undertake its next mission, but then it was no longer necessary. It was clear by now that there would be no pursuit. On November 19, the units of the U. S. First and Ninth Armies were, on average, no more than two miles from their jump-off points, and no unit had gained more than ten miles. The Ninth Army did not reach the Roer until November 28 and did not finish clearing the west bank until December 9, after a twenty-three-day battle in which it pushed forward twelve miles at its maximum point. Before the Siegfried Line, the west bank of the Roer, and the Huertgen Forest were cleared, the Allies would suffer more than 80,000 casualties.