The frontal charge is a desperate thing; and running through so many Civil War battles is a melancholy acceptance of inevitable death: “Every man vieing with his fellowman, in steadiness of step and correct alignment, the officers giving low and cautionary commands, many knowing that it was their last hour on earth, but without hesitating moved forward to their inevitable doom and defeat,” comments Lieutenant L. D. Young, Fourth Kentucky, on being sent into a suicidal attack by General Braxton Bragg at Murfreesboro (Stones River), on December 31, 1862. And surely there is no more heartbreaking image of this stoicism than the veterans of the Twentieth Maine at the Wilderness watching the “spurts of dust … like the big drops of a coming shower along a dusty road” that were erupting all over the field, and then pulling down their caps over their eyes as though this shielding would in some magical way protect them from the murderous storm into which they were about to advance. Or the Irish Brigade advancing up toward Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, heads bowed into the fury.

There was also a fatally self-reinforcing element to the linear attack with men moving “elbow-to-elbow”—something that, after all, increased their chances of being hit. Men packed together and highly influenced by their peer group become more controllable and less able to make individual decisions about their own fates: “Not to put too fine a point on it, you could ensure that men stood and fought—and died—if you had them all enclosed in serried ranks.” William A. Ketcham of the Thirteenth Indiana describes how the influence of his comrades’ opinions channeled him toward the acceptance of death in combat:

After I had got used to fighting and could appreciate my surroundings free from the tremendous excitement in the blood, of the smell of battle, I knew perfectly well all the time that if a cannon ball struck in the right place it would kill or maim.… I knew it was always liable to strike me, but I always went where I was ordered to go and the others went, and when I was ordered to run and the others ran, I ran. I had a greater fear of being supposed to be as afraid as I was than I had of being seriously hurt and that is a great deal of sustaining power in an emergency.

Confederate general John Gordon describes how the enemy was allowed to come “within a few rods (a rod equals 16.5 feet)” and then “my rifle flamed and roared in the Federals’ faces … the effect was appalling. The entire front line, with few exceptions, went down in the consuming blast.” At Antietam, Frank Holsinger recalled how the Sixth Georgia rose up from behind a fence and poured a volley “within thirty feet” that decimated our ranks fully one-half; the regiment was demoralized.”

Close-order firing also had a devastating effect on men in column, especially when delivered by an adversary arrayed in line. A young company commander of the Sixty-Third Ohio Volunteers describes an action on the second day of the battle of Corinth, October 4, 1862:

The enemy had to come over a bluffish bank a few yards in front of me and as soon as I saw their heads, still coming slowly, I jumped up and said: “Company H, get up.” The column was then in full view and only about thirty yards distant.… Just in front of me was a bush three or four feet high with sear leaves on it. Hitting this with my sword, I said: “Boys, give them a volley just over this. Ready! Aim! (and jumping around my company to get from the front of their guns) Fire!” In a few seconds the fire was continued along the whole line.

It seems to me that the fire of my company had cut down the head of the column that struck us as deep back as my company was long. As the smoke cleared away, there was apparently ten yards square of a mass of struggling bodies and butternut clothes. Their column appeared to reel like a rope shaken at the end.

In fact the tactical orthodoxy, as expressed by the leading West Point theorist of the day, Dennis Hart Mahan, writing in 1836, deplored the use of column because it offered a more concentrated target than attack in line: “In a very deep order, the troops readily become huddled by an inequality of motion; the head alone fights … and a fire of artillery on it causes the most frightful ravages.” Its other disadvantage, as French columns during the Napoleonic Wars discovered, was that it could only present a small “face” of muskets as most men were unable to present and fire because they were boxed in.

And yet the suicidal bloodletting of frontal attacks in great sweeping sacrificial lines has to be set against the merciful ineptitude of most soldiers. It takes a lot of lead to kill a man. There was a natural temptation among the inexperienced soldiers who made up the majority on both sides to fire off their muskets with profligate disregard for any tangible result. Captain Frank Holsinger of the Nineteenth US Colored Infantry observed:

How natural it is for a man to suppose that if a gun is discharged, he or someone is sure to be hit. He soon finds, however, that the only damage done, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the only thing killed is the powder! It is not infrequently that a whole line of battle (this among raw troops) will fire upon an advancing line, and no perceptible damage ensue. They wonder how men can stand such treatment, when really they have done no damage save the terrific noise incident to the discharge. To undertake to say how many discharges are necessary to the death of a soldier in a battle would be presumptuous, but I have frequently heard the remark that it took a man’s weight in lead to kill him.

Captain W. F. Hinman, a Union officer at Murfreesboro (1862) described an encounter at long distance:

Within half an hour we stirred up the enemy’s cavalry. Firing began at once, and continued throughout the day. The companies on the skirmish line were kept busy, but as scarcely anybody got hurt they thought it was a good sport.… The shooting made a great deal of noise, although it was about as harmless as a Fourth of July fusillade. But our skirmishers blazed away incessantly. We marched over the body of one rebel who had been killed. Shots enough were fired that day to destroy half of Bragg’s army.

A Confederate officer, I. Herman, observed that most infantrymen went through their allocation of cartridges during an engagement of any length. Five thousand men might easily expend 200,000 rounds in a few hours (an average of 40 rounds per man), and in his experience it took 400 rounds for every enemy killed. General Rosencrans at Murfreesboro estimated 145 shots to inflict one casualty (and not necessarily a fatality). No wonder General James Longstreet could inform his less experienced troops that though “the fiery noise of battle is indeed most terrifying, and seems to threaten universal ruin it is not so destructive as it seems, and few soldiers after all are slain.… Let officers and men, even under the most formidable fire, preserve a quiet demeanor and self-possessed temper.”

George Neese, a rebel gunner, found it “astonishing and wholly incomprehensible” that so many could come through the storm unscathed—“how men standing in line, firing at each other incessantly for hours like they did today, can escape with so few killed and wounded, for when Jackson’s infantry emerged from the sulphurous bank of battle smoke that hung along the line the regiment appeared as complete as they were before the fight.”

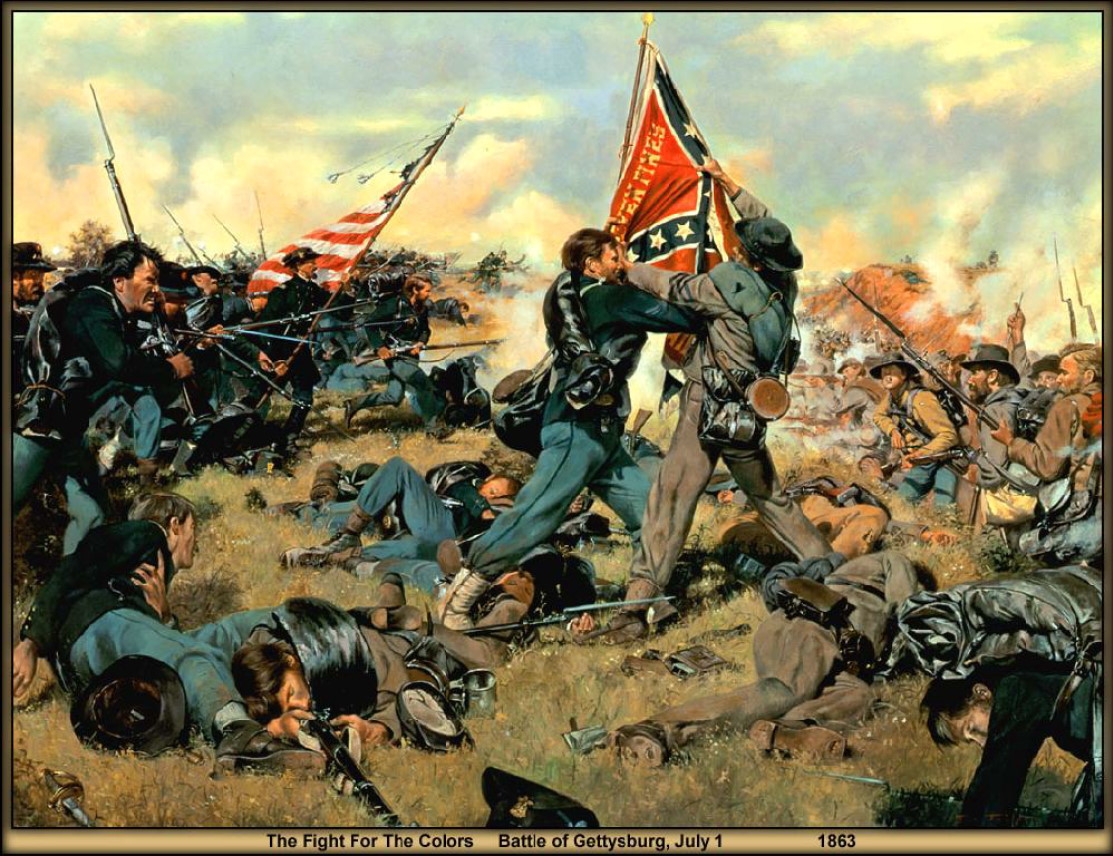

Looking at casualties through the rose-colored lens of the telescope, we see that at Gettysburg, the bloodiest Civil War battle in terms of the total number of casualties, 81 percent of Union and 76 percent of Confederate soldiers came through the three days unhurt. But through the other more sanguine lens we see that one in five Federals and one in four Confederates engaged in the battle became casualties and one in thirty Federals and one in fifteen Confederates were killed.

Although musketry may have been wayward, it was overwhelmingly the main source of death in a Civil War battle. Union field surgeon Charles Johnson declared, “I think wounds from bullets were five times as frequent as those from all other sources. Shell wounds were next in frequency, and then came those from grape and canister. I never saw a wound from a bayonet thrust and but one made by a sword in the hands of an enemy.”The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, published in six volumes between 1870 and 1888 under the auspices of the surgeon general of the US Army, covers Union and Confederate experience. Of the 246,712 wounds from weapons that were treated during the war, the vast majority (just over 231,000) were from small arms. Next came artillery-induced wounds (13,518), followed by a very small number (922) of bayonet wounds. Obviously, if the wounds were treated the soldier had not been killed outright, but the proportion is at least an indicator of the most likely causes of death. The sites of the wounds also tell a story. Most of the wounds (over 70 percent) recorded in the Medical and Surgical History were to the arms and legs, which is understandable because they would have been the more survivable and therefore recorded in wound statistics, although amputation might well claim a life later. In one group of 54 amputees, 32 (60 percent) subsequently died.

It is not surprising that a smaller percentage of wounds were to the face, head, and neck (10.7 percent) and 18.4 percent to the torso because men hit in these areas tended to be killed outright and therefore not become a wounded statistic. As Charles Johnson observed:

When a minie ball struck a bone it almost never failed to fracture and shatter the contiguous bony structure, and it was rarely that only a round perforation, the size of the bullet, resulted. When a joint was the part the bullet struck, the results were especially serious.… Of course, the same was true of wounds of the abdomen and head, though to a much greater degree. Indeed, recovery from wounds of the abdomen and brain almost never occurred. One of the prime objects of the Civil War surgeon was to remove the missile, and, in doing this, he practically never failed to infect the part with his dirty hands and instrument.

When Captain William M. Colby of my company was brought from the firing-line to our Division Hospital he was in a comatose state from a bullet that had penetrated his brain through the upper portion of the occipital bone [the base of the skull]. The first thing our surgeon did was to run his index finger its full length into the wound; and this without even ordinary washing. Next he introduced a dirty bullet probe. The patient died a day or two later.

Some, though, lived to disprove the rule. Corporal Edson D. Bemis of the Twelfth Massachusetts Infantry was shot in the left elbow at Antietam, gut-shot at the Wilderness, and then, almost at the war’s end, shot through the left temple by the ear so that when he arrived at the hospital, brain matter was oozing from the wound. After the ball had been removed, the patient began to recover and by 1870 could write with splendid equanimity, “I am still in the land of the living.… My memory is affected, and I cannot hear as well as I could before I was wounded.”

A head shot was usually fatal, but a body wound might feel surprisingly innocuous. US Seventh Michigan cavalryman A. B. Isham reports that the “first sensation of a gunshot wound is not one of pain. The feeling is simply one of shock, without discomfort, accompanied by a peculiar tingling, as though a slight electric current was playing about the site of injury. Quickly ensues a marked sense of numbness, involving a considerable area around the wounded part.” Another soldier remembers “no acute sensation of pain, not even any distinct shock, only an instantaneous consciousness of having been struck; then my breath came hard and labored, with a croup-like sound.” A truly terrible experience, though, was to see the look on the face of a mortally hit comrade—“a stare of woeful amazement,” recalls one soldier, while another describes a comrade who had been hit in the head, “gasping in that peculiar, almost indescribable way that a mortally wounded man has. I shall never forget the pleading expression, speechless yet imploring.”

Troops and their field officers were caught, as they have been throughout history, in an awful dilemma: on the one hand, having to obey the iron dictates of grand tactics (particularly frontal assaults against well-prepared defenses) that would, in all likelihood, result in many deaths; and on the other, improvising localized tactics that might save their lives but must not be seen, by their lords and masters, to compromise the mission. The terrible experience of the frontal attack led to compensatory tactics that would be repeated in the First World War. Entrenchment was an obvious one, but there was also a movement away from mass to more fluid, fragmented attacking units, which also became a characteristic of World War I combat as the war progressed. More sustained skirmishing as well as attacking in rushes became more frequent. At Spotsylvania in May 1864 the Twelfth New Hampshire took 338 casualties (of whom a staggering 30 percent were killed) out of a starting complement of 549 men; an observer notes that “the terrible experience of the last hour and a half has taught them a lesson that each one is now practicing; for every man has his tree behind which he is fighting.” Charles W. Bardeen, a Union soldier at the battle, illustrated the tactical issue: “[A] heavy artillery brigade that had come into active service for the first time was ordered to recapture a baggage train. The general actually formed his men in solid front and charged through the woods.… Every confederate bullet was sure of its man, and the dead lay thick; I helped bury … more than a hundred. It even failed with its five thousand men to capture the train, and then our poor little brigade, hardly twelve hundred altogether, was sent in, and advanced rapidly, every man keeping under cover in the thick woods and brought in the train, hardly losing a man.”

Confederate tactics, too, cannot be seen only in terms of heroic but suicidal frontal attacks. Left to their own devices, men will adapt if it increases their chances of survival, especially if it happens also to decrease their opponent’s chances. Captain John W. DeForest, in a faithful though fictionalized account, described how his rebel opponents “aimed better than our men; they covered themselves (in case of need) more carefully and effectively; they could move in a swarm, without much care for alignment or touch of elbows [“touch of elbows” was the standard tightly formed advance prescribed for bayonet attacks]. In short, they fought more like redskins, or like hunters, than we.”

There was a parasitical relationship between Civil War artillery and its primary victim, the infantry. Although there had been many innovations in the science of gunnery, particularly in the form of rifled guns and exploding shells, the main source of death was still, as it had been throughout the black-powder era, solid shot delivered either in multiple doses via canister or in one megadose via cannonball. For the artillery to be effective, the infantry had to play along. The guns feasted on men who, through tactical convention, were all too often presented in tight, massed formations, elbow-to-elbow in frontal assault, and artillery fed heartily at close range. Charles Cheney of the Second Wisconsin Infantry at first Bull Run (Manassas) tried to describe what it was like to be under close artillery fire: “None but those who saw it know anything about it.… There were hundreds shot down right in my sight; some had their heads shot off from their shoulders by cannon balls, others were shot in two … and others shot through the legs and arms.… Cannon balls were flying like hail.”

“Death from the bullet is ghastly,” writes a soldier of the Fourteenth Indiana, “but to see a man’s brains dashed out at your side by a grape shot and another body severed by a screeching cannon ball is truly appalling.” The smaller balls of canister shot certainly accounted for many more deaths than solid shot or exploding shell, but they lacked the horrific grandeur of a cannonball: “It is a pitiful sight to see man or beast struck with one of those terrible things.” The “shock-and-awe” factor was reinforced by the thunderous boom of solid shot, and demoralization was almost as important as lethality: “Dead men did not run to the rear spreading panic and demoralization.”

Most artillery on both sides was old-style smoothbore, the aptly named 12-pound Napoleon, 1857 model, firing a 4.62-inch-diameter ball, being the workhorse. The North had many more rifled pieces, such as the Parrott, which gave it something of an advantage in terms of counterbattery actions because of its superior accuracy. On one occasion, in a spectacular example of artillery sniping, Confederate general Leonidas Polk was practically cut in two by a carefully aimed shell from a Hotchkiss rifled artillery piece at Pine Mountain on June 14, 1864. Like musketry, gunnery lethality had more to do with quantity and proximity than with accuracy. It was the uncomplicated and unfussy smoothbore cannon that was the omnivore of the Civil War battlefield. It could be loaded faster than a rifled piece and be switched from solid shot to canister with deadly fluency.

For attacking infantry there were three distinct artillery killing zones to be traversed.

Zone 1: If their starting point was 1,500 yards out from the enemy cannon (a not uncommon jumping-off point), there would first have been approximately 850 yards to traverse (taking about ten minutes at regular pace), within which they might be hit by both percussion-fused shells that exploded on the ground (or not, depending on the reliability of the fuse and the softness of the ground) and shrapnel-like spherical shot that exploded above the attacking troops and scattered pieces of the shell casing as well as the seventy-plus iron balls it contained. During this time each piece of the opposing artillery might get off fifteen to twenty rounds, and the first casualties would begin to fall, although not yet in significant numbers. The problem for the artillerist was that the fuses for the spherical case were crude and the explosion could not always be accurately predicted, a technical difficulty that was compounded when the target was moving rapidly forward. For maximum lethality, spherical shot needed to explode about 75 yards in front and 15–20 feet above the target, which was a challenge for the technology of the time.

Zone 2: The next 300 yards would be taken at the quick step, and during those approximately three and a half minutes, each of the defending cannon would have time to send seven balls plowing their furrows through the oncoming rank and file. With the attackers now at 350 yards away, the gunners would quickly switch to canister. Over the next 250 yards the attackers, now moving at the double-quick step, would have to endure about nine blasts from each gun (for solid shot and shell, two rounds a minute was considered reasonable, compared with three a minute for canister).

Zone 3: For those attackers who had stayed on their feet, there would be an appalling last 100 yards taken at the full-out charge and lasting about thirty seconds, during which time the cannoneers could get off one round of canister at point-blank range. If the situation had become especially tricky for the defenders, the cannon might be “double-shotted”—two cans fired at the same time.

A Civil War soldier, if killed by artillery, would most likely be hit at close range—cut down by canister. Longer-range gunnery tended to be much less lethal, although the Union shells fired at those Confederate troops massing for the attack on the Union center on the third day of Gettysburg caused a considerable number of casualties. A British observer, Arthur Fremantle, embedded with Lee’s army, noted the large number of men who had been hit while in the woods on Seminary Ridge about a mile from the Union guns on Cemetery Ridge. “I rode on through the woods.… The further I got, the greater became the number of the wounded. At last I came to a perfect stream of them … in numbers as great as a crowd in Oxford Street in the middle of the day.” In contrast, the Confederate preattack bombardment on the Union center on the third day of Gettysburg, although delivered by more than 150 guns, was a failure. It had an insignificant impact on the Union infantry, who were sheltered by the wall and topography atop Cemetery Ridge. And partly due to some deft maneuvering of the Union artillery, the bombardment also failed to interdict the Federal cannon, which would reassemble and inflict terrible casualties on the attackers. A Federal artilleryman scorned the Confederate bombardment: “Viewed as a display of fireworks, the rebel practice was entirely successful, but as a military demonstration it was the biggest humbug of the season.”

In some ways the progression of the fighting on the third day of Gettysburg was a chilling preview of many a First World War battle: the artillery barrage that was meant, but failed, to soften up the defenders; the massed attackers moving at an ordered pace across the deep killing ground of no-man’s-land, where they were vulnerable to shrapnel; and the intense defensive firepower at close quarters that destroyed them. An eyewitness on the Federal side describes how the attackers were pulled into a vortex of destruction: “Our skirmishers open a sputtering fire along the front, and, fighting, retire upon the main line.… Then the thunders of our guns, first Arnold’s, then Cushing’s and Woodruff’s and the rest, shake and reverberate again through the air, and their sounding shells smite the enemy.… All our valuable guns are now active, and from the fire of shells, as the range grows shorter and shorter, they change to shrapnel, and from shrapnel to canister, without wavering or halt, the hardy lines of the enemy move on.” A private of the Eighth Virginia remembered from halfway across the valley between the ridges the terrific intensity of the artillery response: “When half the valley had been traversed by the leading column there came such a storm of grape and canister as seemed to take away the breath, causing whole regiments to stoop like men running in a violent sleet.” Captain Andrew Cowan of the First New York Independent Battery describes hitting the Confederates with canister at 20 yards: “My last charge (a double header) literally swept the enemy from my front.”

It is perhaps indicative of the overall picture of officer mortality in the Civil War that the first and last general officers to be killed (Brigadier General Robert S. Garnett, hit by a minié ball at Corrick’s Ford, on July 13, 1861, and Brigadier General Robert C. Tyler, killed by a sharpshooter on April 16, 1865, at Fort Tyler, Georgia) were both fighting for the South. Where more ordinary Confederate soldiers were killed in proportion to their Union counterparts, so too were Confederate officers. One explanation is that there were simply more Confederate officers in proportion to the men they led, compared with the North. In forty-eight battles analyzed by Thomas Livermore, the officer percentage of the Confederate troops was between 6.5 and 11 percent; on the Union side it ran between 4 and 7 percent.

Other explanations hark back to cultural differences between South and North. For the officer class of the South a few cultural streams flowed together. There was the “knightly” ethos of the southern gentleman-officer inspired, for example, by the medieval romances of Sir Walter Scott, which enjoyed a particular popularity. Young blades from the South embraced a cavalier swagger, quick to take offense and unhesitatingly willing to put their lives on the line or to take a life should honor demand it. A traveler in the South noted that the “barbarous baseness and cruelty of public opinion [that] dooms young men, when challenged, to fight. They must fight, kill or be killed, and that for some petty offence beneath the notice of the law.”

Northern officers, by contrast, were seen by the South as percentage players, businessmen at war. As a Confederate diarist puts it: “The war is one between the Puritan & Cavalier”—the flamboyant Celt versus the dull Anglo-Saxon. Although most of this is utter tosh, for Southern nostalgists past and present, heady with Dixiephilia, it can be intoxicating tosh. In any event, such arguments are meant to explain the higher mortality among Confederate officers.

The underlying truth was that officers of both North and South shared a common code that held them to a very high level of commitment and risk. In the Union army the ratio of officers to men was 1 to 28, but the ratio of officers to men killed in battle was 1 to 17. At Shiloh, 21.3 percent of Union officers became casualties, compared with 17.9 percent of men, and at Gettysburg the proportion was 27 percent to 21 percent.

None, not even the most senior, exempted themselves from the danger of being killed—and an extraordinarily large number of general officers were killed in battle on both sides. Sixty-seven Union general officers (including 11 major generals) were killed outright or died of wounds. Fifty-five percent (235 out of 425) of Confederate general officers became casualties, and of those 73* were killed, including 3 lieutenant generals, 6 major generals, and 1 Army commander—A. S. Johnston, killed at Shiloh. Fifty-four (70 percent) died leading their men in attacks. In one battle alone—Franklin, Tennessee, in April 1863—5 Confederate general officers were killed on the field and 1 later died of wounds. At Gettysburg, 7 Union general officers (including those brevetted) and 5 Confederates were killed or died from wounds received in the battle.

It does not do justice to the bravery of the officers of the North, however, to suggest that such sacrifice was in some way characteristic only of the Confederate officer corps, as in “The Confederacy’s code of loyalty, like that of earlier Celts, required officers to lead their men into battle.… Confederate Colonel George Grenfell told a foreigner that ‘the only way in which an officer could acquire influence over the Confederate soldier was by his personal conduct under fire. They hold a man in great esteem who in action sets them an example of contempt for danger.’ ” Exactly the same sentiments were applicable to the North.