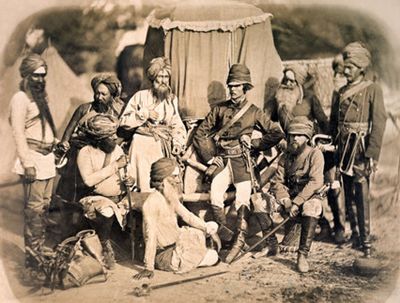

British & Native Officers of Hodson’s Horse, 1858 by Felix Beato

The popular image of an East India Company army officer is of a gentleman, the younger son of a small country squire or vicar who could not afford to set him up at home. Often as not he had Scots or Irish blood and was ‘well-educated, hardy and ambitious’. He tended to be a man of firm religious convictions, and went out to India not only to make his fame and fortune but because he believed it to be his Christian duty.

There were men like this: John Nicholson, of well-born Ulster Protestant stock, who made his name as a political officer on the North-West Frontier before becoming, at thirty-four, the youngest brigadier-general in the Bengal Army; William Hodson, the Cambridge-educated younger son of the Archdeacon of Stafford, who developed into a first-rate intelligence officer and commanded the finest irregular cavalry in India; and ‘Joe’ Lumsden, the scion of a Scottish artillery officer, who pacified the unruly Hazara region with Sikh troops at the age of twenty-five, shortly before founding the Corps of Guides. But these men were exceptional. By the mid nineteenth century the typical Indian Army officer was of modest social origins, ill-educated and only interested in India as a means of bettering himself. ‘People do not come here to live, to enjoy life,’ commented one French traveller in 1830. ‘They come — and this is true of all classes of society — in order to earn the wherewithal to enjoy themselves elsewhere.’

The road north of Delhi was far from secure. On 16 August, 1857 having discovered that a body of mutineers had left the city and were heading north-west towards Rohtak, Archdale Wilson sent Hodson to keep an eye on them. He took with him 100 of the Guides Cavalry, 25 Jhind horsemen and 230 of his own newly raised corps of irregular horse. Smartly dressed in their khaki tunics offset by scarlet sashes and turbans, the Sikhs and Punjabi Muslims of Hodson’s Horse certainly looked the part. But Henry Daly, the commander of the Guides who was recovering from a serious wound, was not fooled. He wrote: ‘Many of the men, hastily collected, caught at the plough’s tail, cut a ludicrous figure mounted on the big, obstinate stud horses with English saddles, bumbling through the Delhi camp.’ Even Hodson was prepared to admit their deficiencies, telling one correspondent that the corps ‘is merely an aggregation of untutored horsemen, ill-equipped, half-clothed, badly provided with everything, quite unfit for service in the usual sense of the term, and only forced into the field because I have willed that it shall be so’. In battle, however, they would prove their worth.

By the end of the first day, defying muddy roads and swollen rivers, Hodson’s column had routed a couple of small bodies of rebel horse and reached the outskirts of Rohtak. But the rebels were holding the town in far larger numbers than Hodson had expected, and, with a direct attack out of the question, he decided to draw the enemy into the open. Next morning, having repulsed one attack by rebel foot and horse, he gave the order to retire. The stratagem worked perfectly:

The enemy moved out the instant we withdrew [he recalled], following us in great numbers, yelling and shouting and keeping up a heavy fire of matchlocks. Their horsemen were principally on their right, and a party galloping up the main road threatened our left flank. I continued to retire until we got into open and comparatively dry ground, and then turned and charged the mass who had come to within from one hundred and fifty to two hundred yards of us. The Guides, who were nearest to them, were upon them in an instant, closely followed by and soon intermixed with my own men.

The enemy stood for a few seconds, turned, and then were driven back in utter confusion to the very walls of the town, it being with some difficulty that the officers could prevent their men entering the town with the fugitives. Fifty of the enemy, all horsemen, were killed on the ground, and many must have been wounded.

With just thirteen casualties, Hodson returned to camp a hero. But his victory was slightly tarnished when word leaked out that, en route to Rohtak, he had executed a ressaldar named Bisharat Ali who had absconded from the 1st Punjab Cavalry. As Ali was caught leading a party of deserters from his regiment, Hodson had a good excuse to kill him. Nicholson and others would have done the same. Unfortunately for Hodson, Neville Chamberlain was an old friend of Ali and not convinced of his guilt. It quickly became camp gossip that Hodson had shot Ali for reasons of personal animosity, rather than summary justice. Nothing came of it, but the mud stuck, leaving Hodson open to more serious allegations of impropriety.

John Nicholson

A week after Hodson’s return, Nicholson left camp with a much larger column of 1,600 infantry, 450 cavalry and 16 horse artillery guns. His orders were to pursue and bring to action a superior force of 6,000 mutineers* and 15 guns which, led by the rebel Commander-in-Chief Bakht Khan, was attempting to intercept the siege-train as it crawled down the Grand Trunk Road towards Delhi. The rebel force had departed a day earlier and, acting on intelligence that it was heading for the canal bridge at Najafgarh, 20 miles west of Delhi, Nicholson moved in the same direction. It was a torturous march: heavy rain had turned the road into a quagmire; in places it was lost in swamps and floods through which the guns had to be dragged by hand. The sun was beginning to set when the advance guard reached a swollen branch of the Najafgarh Canal and got its first sight of the enemy position. It extended from the bridge over the canal proper to the town of Najafgarh, a distance of almost two miles. Expecting an attack across the bridge, the rebels had concentrated their batteries between the bridge on the right of their line and an old serai, a stone enclosure, on their left centre: three guns were on the bridge, four in the serai and three each in two villages in between; all the batteries were protected by entrenchments, parapets and embrasures.

* Composed mainly of the Nimach and Bareilly Brigades.

Nicholson led his troops to a significant victory over the sepoy army at the Battle of Najafgarh.

As the strongest point in the enemy position was the serai, Nicholson chose to attack it first before rolling up the line of rebel guns to the bridge. But first his men had to struggle across the flooded tributary, waist deep in water, under heavy fire from the serai’s battery. Once over, Nicholson led his assault troops — the 61st Foot, the 1st Bengal Fusiliers and the 2nd Punjab Infantry — to a point 300 yards from the serai, where they were ordered to lie down. Then, rising in his stirrups, he reminded them of the words Sir Colin Campbell had spoken at the battles of Chillianwalla and Alma: ‘Hold your fire till you are within twenty or thirty yards of the enemy, then pour your volleys into them, give them a bayonet-charge, and the serai is yours.’ Soon after, the battery of horse artillery galloped up, unlimbered and opened fire with roundshot on the serai. ‘The order was then given to the attacking column to stand up,’ recalled ‘Butcher’ Vibart, who was with the 1st Bengals, ‘and having fixed bayonets, the three regiments, led by General Nicholson in person, steadily advanced in an almost unbroken line to within one hundred yards of the enclosure, when the word of command rang out from . . . Major Jacob, “Prepare to charge!” “Charge!”’

On they ran through a storm of musket-balls and grape. Nicholson’s horse was hit, forcing him to continue on foot; Vibart had a narrow escape when a bullet deflected off the blade of his sword. ‘Thank you, sir,’ cried a soldier in the ranks behind him, ‘that saved me.’ The first officer to cross the stone wall was Lieutenant Gabbett of the 61st. As he made for the nearest gun he slipped on the wet ground and was bayoneted by a ‘gigantic pandy’; but Captain Trench, Nicholson’s ADC, ‘quickly avenged his death by bringing down the rebel with his revolver’. Within minutes the assault troops had ‘scaled the walls, carried the serai, and captured all the guns’. Vibart recalled: ‘Only a few of the rebels fought with any pluck, and these were seen standing on the walls, loading and firing with the greatest deliberation until we were close upon them. But few of these escaped, as they were nearly all bayoneted within the enclosure.’

Now, changing front, the British column swept along the entrenchment to the bridge, capturing thirteen guns and driving the enemy before it. Lieutenant Griffiths of the 61st Foot recalled:

Our Horse Artillery, under Major Tombs, mowed down the fugitives in hundreds, and continued following and firing on them till darkness set in. The cavalry also — a squadron of the gallant 9th Lancers, with the Guides and Punjabees — did their share of work, while the European infantry were nobly supported by the corps of the Punjab Rifles, who cleared the town of the sepoys. The battle had lasted a very short time, and after dark we bivouacked in the pouring rain, completely exhausted from our long march and subsequent fighting, and faint from want of food, none of which passed our lips for more than sixteen hours.

But one village to the rear still held out. ‘I immediately sent orders to Lieutenant Lumsden [of the 1st Punjab Rifles] . . . to drive them out,’ wrote Nicholson, ‘but though few in number, they had remained so long that our troops were on all sides of them, and seeing no line of retreat they fought with extreme desperation.’ The initial assault was repulsed and Lumsden killed. So the 61st joined in, but they ‘met with only partial success . . . the enemy evacuating the place during the night’. That apart, the action had been the most decisive since Badli-ki-Serai: all but two of the rebel guns had been captured; the vaunted Nimach Brigade, the victor of Sasia, had been comprehensively defeated; and the only bridge by which the mutineers could get to the British rear had been captured and destroyed. But Nicholson had been lucky: he had caught the Nimach Brigade alone because its commander had refused to cooperate with the Rohilkhand Brigade of Bakht Khan, his nominal superior, which was four miles further on and ‘unable or unwilling to come up’. The rebel casualties, according to Munshi Jiwan Lal, were ‘a thousand killed and wounded’.

On hearing of the Nimach Brigade’s defeat, Bakht Khan made straight for Delhi, where the King accused him of being ‘false to his salt’ for ‘turning away from the field of battle’. The King did not relieve him of the Supreme Command because there was no obvious alternative. Yet Bakht Khan’s failure to engage the British at Najafgarh had destroyed his credibility in the eyes of many mutineers. They were, in any case, still unhappy about their pay.* On 1 September five hundred officers and nobles attended a royal durbar to discuss the issue. According to Munshi Jiwan Lal, a number of those present ‘were loud in their complaints that Mirza Mogul and Mirza Kizr had taken several lakhs of rupees from the people in the city, and had given nothing to the Army, and prayed the King to insist on them disgorging some of the money, threatening to arrest and imprison them’. The upshot of this stormy meeting was that the rebel officers were promised the first instalment of their pay in a day’s time and the balance within two weeks. This seemed to satisfy them and they re-joined their regiments.

Nicholson, meanwhile, had returned to Delhi a hero. In under two days his men had marched 40 miles, won a battle against a superior force, captured thirteen guns and demolished a key bridge. ‘Considering that the country was nearly impassable from swamps,’ wrote an admiring Wilson to his wife, ‘I look upon it as one of the most heroic instances of pluck and endurance on record, and [it] does credit as well to Nicholson as the gallant fellows under him.’ Sir John Lawrence was just as impressed. ‘I wish I had the power of knighting you on the spot,’ he wrote to Nicholson from Lahore. ‘It should be done.’