The Iraq War (2003-2011) has its roots in the 1991 Persian Gulf War (also known as Operation Desert Storm) in which the United States, in conjunction with a coalition of forces from 35 countries, worked to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Following the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the United Nations (UN) imposed sanctions on Iraq, calling for Iraqi president Saddam Hussein to destroy the country’s arsenal of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Over the next decade, however, Hussein repeatedly evaded attempts by UN weapons inspectors to ensure that the sanctions were enforced. Upon assuming the U. S. presidency in January 2001, George W. Bush and his administration immediately began calling for renewed efforts toward ridding Iraq of WMD-an endeavor that greatly intensified after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

In Bush’s 2002 State of the Union Address, he castigated Iraq for continuing to “flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror” and called the Middle Eastern nation part of “an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world.” In the months that followed, the U. S. president increasingly spoke of taking military action in Iraq. Bush found an ally in British prime minister Tony Blair, but pressure from citizens of both countries pushed the two leaders to take the issue before the UN Security Council in the form of UN Resolution 1441, which called for UN weapons inspectors, led by Hans Blix, to return to Iraq and issue a report on their findings.

On November 8, 2002, the 15-member UN Security Council unanimously passed the resolution, and weapons inspectors began work on November 27. On December 7, Iraq delivered a 12,000-page declaration of its weapons program, an insufficient accounting according to Blix, and a month later Bush stated that “If Saddam Hussein does not fully disarm, we will lead a coalition to disarm him.” Bush and Blair actively sought the support of the international community, but their announcement that they would circumvent the UN if necessary ruffled many nations’ feathers, most notably drawing the ire of France, Germany, and Russia, all of which pushed for further inspections. Spain joined with the United Kingdom and the United States to propose a second UN resolution declaring Iraq to be in “material breach” of Resolution 1441. Although a small number of other nations pledged their support for military action in Iraq, only Australia initially pledged to commit troops to fight alongside British and U. S. forces.

Opting for a preemptive strategy instead of risking a potential repeat of the September 11 terror attacks-with the added specter of chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons- Bush and his advisers (principally Vice President Dick Cheney and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz) decided to act, unilaterally if necessary. Armed with a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) report regarding Iraq’s possession of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction (the accuracy of which has since been called into question), Bush obtained a legal justification for invading Iraq when in October 2002 the Senate approved the joint resolution “Authorization for Use of Military Force against Iraq Resolution of 2002.” In February 2003 Secretary of State Colin Powell addressed the UN Security Council with information based largely on the same flawed CIA report, but action was blocked by France, Germany, and Russia. Although Britain and 75 other countries joined Bush’s “coalition of the willing” (contributing troops, matériel, or services to the U. S.-led effort beginning in 2003), the absence of France and Germany left his administration open to strong criticism for stubbornly proceeding without broad-based European support.

Bush’s proactive rather than reactive strategy was viewed as a sea-change departure from that of his predecessor Bill Clinton, exposing him to further criticism. Condemnation was heaped on the president for attempting to conduct simultaneous operations in Iraq and Afghanistan with a force stretched thin by military drawdowns con- ducted during the Bill Clinton presidency. On the eve of the Iraq invasion U. S. Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki told the Senate Armed Services Committee that an occupation of that country would require “several hundred thousand” troops, an estimate that, in hindsight, seemed prescient, but was sharply criticized in 2003 by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and his deputy Paul Wolfowitz as “wildly off the mark.”

Facing the disapproval of the British public, Prime Minister Tony Blair pushed for a compromise that would give weapons inspectors a little more time to inspect Iraq. However, with two permanent members of the Security Council-France and Russia- threatening to veto the resolution, the proposal was withdrawn. Undeterred by that set of events, or the Turkish government’s refusal to allow coalition troops to use Turkey as a platform for a northern invasion of Iraq, Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein on March 17 to leave Iraq within 48 hours or face military action. Hours before the dead- line was to expire, Bush received intelligence information that Hussein and several top officials in the Iraqi government were sleep- ing in an underground facility in southern Baghdad called Dora Farms. Bush ordered a decapitation strike aimed at killing Hussein, which took place in the early morning of March 20. Dozens of Tomahawk missiles with 1,000-pound warheads were launched from U. S. warships in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. They hit their targets in Baghdad and were followed immediately by 2,000- pound bunker-buster bombs dropped from F-117 stealth fighters. The war had begun.

That same day (March 20, 2003) U. S.-led coalition troops (which included British forces plus smaller contingents from Australia and Poland) crossed the border from Kuwait into Iraq. The 297,000-strong force faced an Iraqi Army numbering approximately 375,000, plus an unknown number of citizens’ militias. Armed with technology that included stealth bombers and precision-guided (smart) bombs, the coalition commenced its shock- and-awe campaign, designed to stun and demoralize the Iraqi Army into a quick sur- render. Within a matter of days, the coalition had overtaken Basra, Iraq’s second-largest city, as well as the port city of Umm Qasr and the city of Nasiriyah straddling the Euphrates River. While Iraqi soldiers did not surrender with the same celerity as they had in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, nearly 10,000 Iraqi troops surrendered to coalition forces during those first days. Still, the coalition troops were caught unprepared by some of the Iraqis’ guerrilla tactics, including faking surrenders and ambushing troops from the rear.

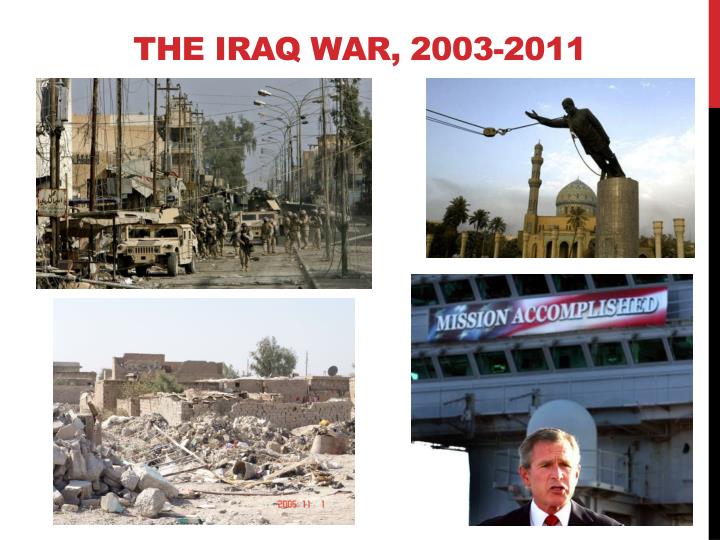

As the war began, two ground prongs struck north from Kuwait, while special forces and airborne forces worked with the Kurds in the north in a limited second front. The ground advance north was rapid. After securing southern Iraq and its oil fields, coalition soldiers began moving toward Bagh- dad; they secured an airfield in western Iraq and Hussein International Airport (immediately renamed Baghdad International Air- port) with little difficulty. On April 5 and 7 coalition forces entered Baghdad where they destroyed many of Hussein’s government buildings and palaces on the Tigris River. Six days later the United States declared the end of Hussein’s regime. The vanquished Iraqi dictator was in hiding. One last hurdle remained, and by April 14 coalition forces accomplished it by capturing Hussein’s hometown of Tikrit. Formal military action ceased, with fewer than 200 confirmed coalition deaths.

It is important to note the speed and success of this first month of Operation Iraqi Freedom-the Iraqi military was destroyed, and the Iraqi government was toppled in less than a month. The U. S.-led coalition captured a country the size of California faster than any land force in history.

In the weeks after the Battle of Tikrit, coalition forces began searching for WMD as well as Saddam Hussein and other top Iraqi officials. Although numerous caches of WMD were uncovered, the troops were unable to find an active WMD program. The lack of an active weapons program combined with the looting of historic treasures from Iraqi museums (which the coalition failed to protect) drew sharp criticism from those who opposed the coalition’s presence in Iraq. Support for the war was further compromised by the fact that the search for Saddam Hussein took longer than anticipated. He was eventually captured in December 2003, brought to trial, found guilty, and executed on December 30, 2006. Although many Iraqi citizens and neighboring countries were very happy to see Hussein’s regime toppled, many others protested the continued presence of coalition forces and the influence they had in the new Iraqi government.

Bush appointed L. Paul Bremer to govern Iraq through the Coalition Provisional Authority, whose stated aim was to reconstruct Iraq as a pluralistic democratic state. The ensuing occupation was plagued by violent resistance, which greatly hampered the economic and political reconstruction of the country, preventing international aid organizations from working in Iraq and discouraging badly needed capital investment. An interim constitution was signed in March 2004, and on June 28, 2004, sovereignty was transferred to the Iraqi people. On January 30, 2005, Iraq held its first open election in half a century, selecting a 275-member transitional National Assembly. Despite the withdrawal of several Sunni parties from the poll and threats of election day violence from insurgents, turnout was high. After two months of deadlock, on April 6 the new legislature elected Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani as president and Ibrahim al-Jaafari as prime minister. In April 2006 Talabani was reelected, and Nuri al-Maliki was selected to succeed al-Jaafari as prime minister. Maliki governed until September 2014, at which time a potent new insurgency, driven largely by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), forced him to resign. The country continues to struggle with sectarian issues and associated violence.

Although Bush famously declared the end of major combat operations while aboard the U. S. aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, this declaration proved to be premature. Deadly guerrilla attacks against U. S. troops continued and increased. Although only 139 U. S. personnel and 33 British soldiers died during the invasion, nearly 4,500 Americans died thereafter in the insurgency that accompanied the occupation. In addition to the attacks conducted against coalition forces following the invasion, major violence broke out between Shiite and Sunni insurgents, causing many observers to begin calling the conflict a civil war.

In many ways, what is called Operation Iraqi Freedom or the Iraq War was two wars. The first was the war against the government and military of Saddam Hussein and lasted slightly more than three weeks. The second war was a fight against a variety of resistance and insurgent groups and lasted for more than eight years. The technological prowess of the West was clearly on display in that first war, and the regional and cultural ignorance of the West was on display in the second war.

The fighting in Iraq was supposed to change from combat operations to a short occupation and handover to a new Iraqi government. Actions with respect to the conduct of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) impeded the possibility of such a transition if that possibility really existed at all. The transition turned into a prolonged occupation of a country that evolved into sectarian civil war. There are several reasons for the failure of the rapid transition plan.

First, the Iraqi governing councils, and later their elected representatives, had little control over the resources and organs of a state. The infrastructure of Iraq was in shambles. This was in part a result of combat action in the spring of 2003 and in part left over from the combat actions of 1991. Economic sanctions imposed on Iraq from 1991 until 2003 also played a role in the disarray and chaos of the Iraqi state. Saddam used what money he obtained during the sanctions to maintain his security and intelligence apparatus and make sure those most essential or loyal to him received the benefits of modernity-electricity, clean water, etc. Meanwhile, the Iraqi people, in general, suffered as their infrastructure degraded.

Second, those initially designated to be in the interim governing body were not respected by the Iraqi people as they were either seen as outsiders (exiles given power by the invaders) or as lackeys to the invading forces. To gain credibility it was almost necessary to be seen as opposing the Coalition Provisional Authority or at least not kowtowing to them in every action. Thus, nothing moved as quickly as expected. “Everything in Iraq is hard” became one of the most often repeated phrases by coalition soldiers and officials. It was said because it was true.

Third, there were several relatively rapid elections. No one governed for any significant length of time in Iraq until well into this period. This almost continuous hand over of authority from one to the next fostered a sense of corruption as a means of survival. Thus, little was really accomplished with the resources provided because those resources were often squandered or horded and then sent to out-of-country estates and banks for later use and benefit.

Fourth and most important, were the Bush administration decisions to dismiss Baath Party officials (essentially, Iraq’s only trained administrators) and disband the Iraqi Army (which at one stroke dumped nearly 400,000 trained soldiers and potential insurgent recruits into the Iraqi general population). The orders, known as Coalition Provisional Orders (CPA) 1 and 2, flooded Iraq with disgruntled, unemployed people and left the country rudderless. No one remained with the expertise or know-how to run the government and meet the basic needs of the people. In addition, lots of young, military trained people and nearly all those who were trained to organize and lead were suddenly without meaningful employment for themselves or their families. Their world was destroyed.

Following the departure of the CPA, the early governing officials experienced longer, though still short opportunities to govern. There was something of a sovereign government in Iraq. However, there was also growing violence. The violence coalesced and transformed. It began as simple banditry but became more ideological in nature with the bombing of the al-Askari shrine and mosque in Samarra and the rise of Al Qaeda in Iraq.

One of the biggest problems was the growing disconnect between the coalition’s perception of what was happening and what was actually happening. It took time for the United States and other members of the coalition to comprehend the rise of a sectarian ideological struggle in Iraq. The U. S.-led coalition began to fall apart in 2004 with nine countries withdrawing their forces. The most famous of the withdrawals was the Spanish contingent who departed after the Madrid bombings in 2004. Two more countries departed each in 2005 and 2006.

General George Casey was tasked to get the Iraqi Army sufficiently ready to transition responsibility and depart within 18 months- or by January 2006. That did not happen as the violence only increased. General Casey believed that limited American participation and visibility would both encourage Iraqis to step forward and discourage attacks on U. S. forces.

Many in the Bush administration and Multi-National Force-Iraq (MNF-I) hesitated to call what was happening in Iraq a civil war, as if the term alone had power. Throughout the war in Iraq there were challenges with regard to labeling what was happening. Were the opposition “dead-enders” or “Ba’athists,” or were they “opposition” or “insurgents”? No term was fully embraced until long after the term had become obvious. Many of the terms and labels had political overtones either in Iraq, the Middle East, or Washington, DC. Insurgents brought to mind Vietnam and the failures associated with that war. Opposition was reminiscent of Palestinians opposing the occupation of their territories by Israeli forces. For these reasons and others, word choice was challenging.

In 2007 the Bush administration implemented a troop surge in Iraq, increasing the troops present in Iraq by as many as 40,000. The additional forces temporarily reduced the potency of the insurgency. Nevertheless, by late 2008 the U. S. public’s support for the Iraq War had plummeted. A status of forces agreement was subsequently negotiated between the U. S. and Iraqi governments that required U. S. combat troops to leave Iraqi urban areas by the end of June 2009 and leave the country entirely by the end of 2011. Soon after taking office in early 2009, President Barack Obama announced that most U. S. troops would exit from Iraq by the end of August 2010, with a smaller transitional force remaining until the end of 2011. The war was declared officially over by the U. S. military on December 15, 2011; by that time, more than 1 million members of the armed forces had served in Iraq, nearly 4,500 Americans had died in the conflict, and some 34,000 others were wounded in action.

Unfortunately, sectarian violence and radical Sunni Islamic extremism in Iraq increased after the U. S. military withdrawal. These developments were aided by the policies of Maliki, whose government brutally repressed Iraq’s Sunni population and shut it out of national governance. By January 2014, rebels associated with ISIS demonstrated significant influence in virtually all of Anbar Province, including Fallujah, where U. S. forces had fought two bloody battles to save the city during the Iraq War. Within days, the Sunni rebels displayed control of the city of Ramadi, also in Anbar Province. The most significant event was the capture of the city of Mosul in June 2014 and the declaration of the caliphate by Abu Bakr al- Baghdadi. The situation underscored the inability of the Maliki administration to gov- ern the country effectively. As the security situation worsened throughout much of 2014, calls for Maliki’s removal from office intensified-both in Iraq and abroad. Finally, in September 2014 he reluctantly resigned and was replaced by the more level- headed Haider al-Abadi.

At that point, the Islamic State, or ISIS, had seized control of large portions of Iraq. By late summer of 2014 the United States was conducting airstrikes on Islamic State targets in Iraq, and in the fall of that same year U. S. forces returned to Iraq at the invitation of the Iraqi government. Their purpose was to train, advise, and equip the Iraqi Army in its fight against ISIS. Gradually over the next three years the territory claimed by the Islamic State was regained by the Iraqi military, and in December 2017 the government of Iraq announced the defeat of ISIS. That said, more than 10,000 American military personnel and security-related contractors remain in Iraq at the time.

Also of note with regard to the current U. S. role in Iraq is the change in perspective between the Obama administration and the Trump administration, which took over in January 2017. The Obama administration had as its goal the defeat of ISIS. The Trump administration has upped the ante by declaring a desire not only to defeat but to annihilate ISIS. In support of this aim, the Trump administration has indicated a need for continuing U. S. presence in Iraq for the foreseeable future with the goal being to provide stability and support in a post-ISIS environment.