Once the last units had joined his line at about 8 a.m., Wolfe ordered his men to lie down so that they would not present easy targets for the snipers. On both sides – in the woods to the British left and in the cornfields between the British right and the cliff edge – the Canadian and Indian sharpshooters had been eerily accurate and effective since first light. Wolfe feared the winnowing effect on his men if they remained upright, for in his mind he had to wait for Montcalm to make the first move so that he could deliver a close-quarter musketry broadside and end the battle within minutes. Howe’s Light Infantry made some early sorties to try to drive the snipers from their positions, but they in turn were driven back at around eight o’clock when the French artillery opened up. When Montcalm’s five fieldpieces began lobbing cannonballs towards the British lines and the redcoats could see the lethal projectiles often skipping over the grass towards them like bouncing bombs, it was the merest common sense to fall prone and present the smallest possible target. Wolfe ostentatiously walked up and down the lines, as if tempting the snipers and artillerymen to take him out. But he would remain a worried man until Montcalm ordered a charge. Time was against him, for if Bougainville arrived soon, Wolfe might be caught in an almost perfect three-way trap, between snipers, Montcalm and Bougainville, with no escape route except the perilous descent to l’Anse au Foulon.

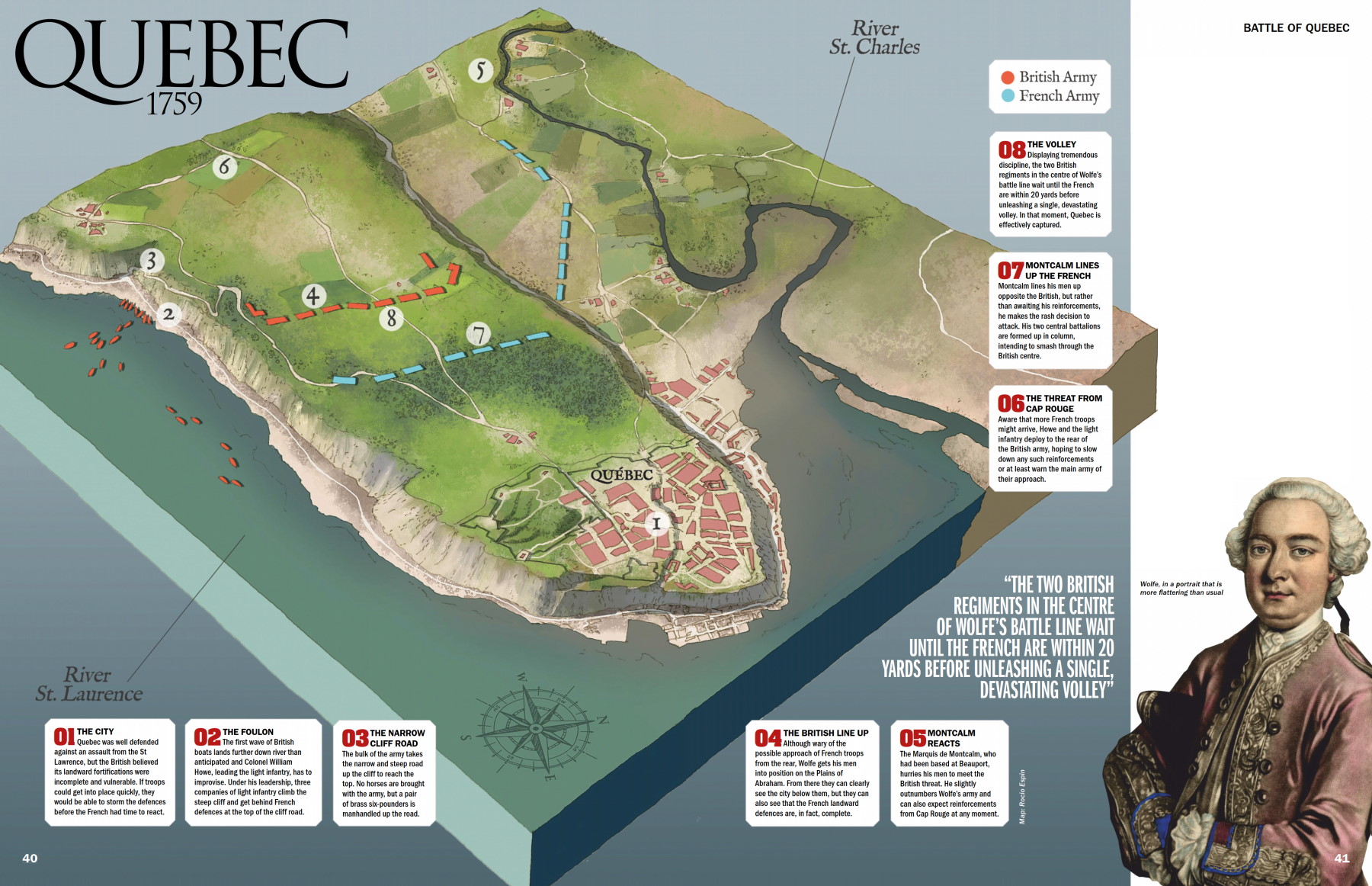

Since time was on his side, Montcalm should at all cost have waited for Bougainville. But his impatience with that officer was like that of Napoleon with Marshal Grouchy at Waterloo fifty-six years later. After asking exas-peratedly where Bougainville was, at 9.30 a.m. Montcalm gloomily told his chief of artillery: ‘We cannot avoid action; the enemy is entrenching, he already has two pieces of cannon. If we give him time to establish himself, we shall never be able to attack him with the sort of troops we have.’ He then added with a grimace: ‘Is it possible that Bougainville doesn’t hear all that noise?’ Had Montcalm known that Wolfe was not entrenching, he would have taken heart. But fatalistically he gave the order to his men to advance. Nothing better exposes Montcalm’s limitations as a commander, for the order to an army largely composed of irregulars to charge a disciplined red line could have only one outcome. Since the British line extended virtually from the St Charles’s escarpment on Montcalm’s right to the St Lawrence cliffs on his left, there was no room to maneouvre and no prospect of encircling or outflanking the enemy. It would be a desperate, bloody affair of musketry and bayonets, where Wolfe’s redcoats were bound to win. Montcalm should have corralled his impatience and waited for Bougainville to arrive, however agonising the wait. So it is a fair judgement to say that the outcome of the battle hinged on Bougainville. What was he doing while all these dramatic developments were unfolding?

The sober answer is that Bougainville’s movements on the night of 12–13 September are hidden from documented history; the scope for the historical novelist and the conspiracy theorist is clear, especially as educated speculation can really shed no light on the matter. According to one version, Bougainville went upriver from Cap Rouge to Pointe-aux-Trembles. Most likely he simply remained inactive and supine at Cap Rouge. Bougainville was a great man, as his later career would prove, but the night of the 12th–13th was not his finest hour. He must have seen the British flotilla going downriver but too glibly assumed that it was the French supply convoy. Yet since it is inconceivable that he did not know the sailing of this convoy had been cancelled, his failure to act seems incredible. The traditional explanation is that he could not reinforce Montcalm as soon as news of the landing at l’Anse au Foulon came in, because his men were worn out by the constant marching and counter-marching involved in the surveillance of the British fleet. But the last movement of the British fleet in Bougainville’s sector had been the abandoned upriver landings on 9 September. While not necessarily as fresh as paint, his men should have been ready for a forced march on the morning of the 13th. Bougainville’s apologists stress that it was Vaudreuil who was liaising with Bougainville and that he did not send a clear order to march towards Quebec when he wrote to Bougainville at 6.45 a.m that morning, nearly three hours after the British landing. This in turn allows one faction of the conspiracy theorists to switch attention away from Bigot and Bougainville and locate the trouble once again in Vaudreuil’s insane jealousy of Montcalm. Could it be that Vaudreuil did not issue the order to Bougainville because he did not want Montcalm to win a victory that day? But nothing can really absolve Bougainville just as nothing could later absolve Grouchy. Whatever the clarity or turbidity of orders, it must always be the duty of a subsidiary commander to march towards the sound of the guns unless the supreme commander has already given explicit orders not to.

At 10 a.m. Montcalm finally gave the order to attack. But even before full battle was joined, there had been some ferocious, bloody fighting on the St Charles side of the lines (the British left) as French colonial regulars and militiamen clashed with the Royal Americans. A running fight, sometimes involving hand-to-hand combat, developed around a pair of farmhouses, which changed hands at least once and were finally gutted when caught in the middle of a grim artillery duel. Even while this sanguinary encounter was being played out, Montcalm gave the signal to advance. The French whooped with delight and came on at the double, much too fast given that they had to cover 500 yards to the British lines. It soon became apparent that Montcalm’s policy of melding militia and regulars in a regular battalion was a disaster, as Major Malartic of the Beam battalion explained: ‘We had not gone twenty paces when the left was too far in rear and the centre too far in front.’ At ‘half musket shot’ (between 125 and 150 yards) the French halted, went down on one knee and fired a stuttering volley. The regulars fired in platoon volleys, but the militiamen discharged wild shots. Even worse, each executed the manoeuvre in a totally different way. The regulars remained standing upright in ranks to reload, while the militiamen, accustomed to forest fighting where one sought cover before reloading, threw themselves prone on the ground and began fumbling with their muskets; as Malartic remarked acidly, reloading from the prone position was not easy. He summed up the indiscipline of Montcalm’s force: ‘The Canadians who formed the second rank and the soldiers of the third fired without orders, and according to their custom threw themselves on the ground to reload. This false movement broke all the battalions.’

Many of the attackers never advanced beyond this point but seemed to have veered off to the right when they picked themselves off the ground. Those of the French who did advance progressed to within forty yards of the British lines, where the redcoats awaited them impassively. They then discharged a devastating relay of fire, with each battalion commander judging the killing ground for himself and firing when ready. Despite the hyperbolic chauvinism of Sir John Fortescue, who claimed that the French ran into ‘the most perfect volley ever fired on a battlefield’ – an obvious exaggeration since nobody could coordinate a single volley along such a widespread line – it is clear that the French reeled under the impact. When the smoke cleared, the British advanced a few yards and fired again. This time there does seem to have been a more coordinated volley, for the result was described as ‘like a cannonshot’. At a range of maybe twenty to thirty yards eighteenth-century musketry doled out fearful damage. After a few terrible minutes the French wilted under this cannonade, broke and began fleeing back towards Quebec. With a cry of ‘Claymore!’, the Fräsers swept after them with the broadsword, but this time the famous Highland charge did less damage than on other notable occasions. So rapid was the rout of the French that the pursuers never caught up with the main army.

It was probably the first French volley, 150 yards out, that dealt Wolfe his death-stroke. Standing on a rise near the Louisbourg Grenadiers, he first sustained a shattered wrist (which he bandaged with a handkerchief), and then a fatal wound in the right of his chest; there may have been an additional hit from a spent bullet in the groin or lower belly. Haemorrhaging uncontrollably, he remained conscious long enough to learn that he had been victorious. Many Wolfe students are convinced that he went into battle certain that he had but a short time to live and determined to pre-empt disease by a glorious death in combat. Certainly the evidence is overwhelming that he deliberately exposed himself to gunshot, and his most vehement critics even assert that in his overpowering death-wish he actually neglected the interests of his troops and exposed them to great peril on the Heights of Abraham, from which only Montcalm’s folly in seeking an early battle rescued them.

In death Wolfe won the eternal glory he lusted after. One of the most famous of all historical paintings, by Benjamin West, shows his senior officers clustered around him, listening to words of wisdom from the fallen hero, while an Indian ally looks on pensively. Need we say that there was no Indian ally present and that his officers did not cluster round him? The most accurate account of Wolfe’s last moments records that he rejected the ministrations of a surgeon on the grounds that he was too far gone. Then, hearing the words ‘They run!’, Wolfe enquired who it was that ran. An officer replied: ‘The enemy, sir; Egad, they give way everywhere.’ Wolfe replied: ‘Go one of you, my lads, to Colonel Burton; tell him to march Webb’s regiment with all speed down to Charles’s River, to cut off the retreat of the fugitives from the bridge.’ He then turned on his side and said: ‘Now, God be praised, I will die in peace.’ Within seconds he was dead.

By a bizarre synchronicity Montcalm was mortally wounded only minutes later, during the confused rush of the defeated French back to Quebec. There is dispute about whether he was wounded by grapeshot from a British six-pounder or was deliberately and cynically taken out by British snipers. His wounds were in the lower part of the stomach and thigh and although he did not bleed to death on the field like Wolfe, he was a dying man and he knew it. Three soldiers supported him in the saddle as he rode painfully back to the city; he lingered on until 4 a.m. on the 14th. Like Wolfe, he became the subject of myth-making. Jean-Antoine Watteau’s painting The Death of Montcalm is a visual riposte to Benjamin West. Once again we see the hero dying on the battlefield (in fact Montcalm was buried in the Ursuline convent), and once again Mohawk warriors, never at the centre of the action historically, occupy a prominent position in the iconography. Montcalm’s death had more immediate effects. Since his two brigadiers, Fontbonne and Senesergues, had also received mortal wounds, there was a power vacuum in the French army. All was chaos, with no one knowing casualty figures or those of the enemy, Bougainville’s whereabouts unknown and Vaudreuil still in the Beauport camp, dithering and procrastinating.

When the Fräsers unsheathed their claymores and charged off in pursuit of the stricken French, they were soon followed by the English regiments with fixed bayonets, all advancing across a field where the scattered showers of the morning had given way to sunshine. It was in this sunlit aftermath of the battle proper that the heaviest casualties occurred. In the woods just east of the spot where Montcalm had formed his line, hundreds of Canadians, now in their element among the gloomy trees, turned to face their pursuers. A particularly sanguinary fight ensued between the 78th Fraser’s Highlanders and the Canadians, both wilderness fighters of high calibre. Murray later reported that the enemy ‘killed and wounded a great many of our men, and killed two officers, which obliged us to retire and form again’. It was only with the aid of the 58th Highlanders and the Royal Americans that the Fräsers were finally able to flush their doughty opponents out of their wooded foxholes and drive them down the hill and over the St Charles, though in the latter stages the Highlanders came under fire from the Canadian hulks in the mouth of the St Charles. This valiant rearguard action enabled the defeated French army to make good its escape over the bridges to the Beauport camp. Meanwhile the Louisbourg Grenadiers on the British right had also taken some punishment from the snipers who still remained in the corn field. It was at this stage that Townshend assumed command and at once called off the pursuit.

Townshend has been criticised for excessive caution in not pursuing the French at all costs. But he sensed that in the post-battle blood-lust his troops were losing their discipline and degenerating into a rabble. It was important to restore order before Bougainville put in an appearance. It took time for his officers to reinstate discipline and the British army had only just re-emerged as a fighting force rather than a rabble when Bougainville’s force duly arrived. Outnumbered two to one in this theatre, Townshend faced around and placed two battalions and two big guns across the path Bougainville would have to tread in order to relieve Quebec. Taken aback by the enemy’s boldness and stupefied to learn that Montcalm had already been defeated, Bougainville did not stop to consider that he had a local superiority, but sheered off to the Sillery Woods to contemplate his next move. Townshend’s actions were correct, for the power vacuum following Wolfe’s death left the British troops concentrating on gung-ho mopping-up operations instead of moving swiftly to cut off the French retreat. But there was a lack of leadership for a vital hour and in that time a great opportunity was missed. Nobody followed up on Wolfe’s dying prescription that the St Charles bridges be seized, and the result was that the French army, though defeated, was not destroyed. The long-term consequences were that Britain had to campaign in North America in 1760, and for that Townshend, most unfairly, was held to blame.

The battle on the Plains of Abraham was a notable victory, but it was expensively purchased. British casualties amounted to 658, including fifty-eight killed. Fraser’s Highlanders bore the brunt of the losses, with 168 dead and wounded, and the attrition rate was high among the officer classes, with Monkton, Carleton and Barre all wounded. Vaudreuil posted losses of about 600 men and forty-four officers. Normally the losers in an armed encounter suffer casualties way above those of the defeated, but in this case the near-equality of suffering is explained by the damage done by Canadian snipers before the battle and by the colonial militia in the bloody post-battle combat with the Highlanders in the woods. Yet the French were utterly demoralised and it was 6 p.m. that evening before Vaudreuil could collect his wits sufficiently to convene a council of war. It was put to him that he had but three choices: he could make a fresh attack on the enemy; surrender the whole of New France; or retire to continue the fight on the Jacques Carrier river. Because of the demoralised state of the army and the lack of provisions, only withdrawal made sense. Abandoning all heavy artillery and much of their ammunition, the French soldiers stole away along the east bank of the St Charles river and made a forced march to Pointe-aux-Trembles on the 14th whence they continued to the Jacques Cartier.

The useless Vaudreuil, having fled with the army, further ruined French prospects by three separate actions. He failed to move any of the food and supplies from the Beauport camp into Quebec to help the besieged garrison and civilians he left behind. He wrote out draft articles of capitulation for the use of the hapless individual he left as commandant of Quebec, Jean-Baptiste de Ramezay. And he told Ramezay that on no account was he to hold out in Quebec beyond the exhaustion of his food supplies; this effectively meant an order to surrender in three days. Vaudreuil compounded his fatuity by drafting long letters to Versailles, pinning the blame for the recent defeat on Montcalm, maligning the dead hero and mendaciously suggesting that Montcalm had only ever achieved military success when he followed his (Vaudreuil’s) prescriptions.

Ramezay was thus left with a mission impossible – having to defend Quebec with little more than 2,000 demoralised men, while being plagued with the defeatism of 4,000 civilians, sick and wounded, all of them on the brink of starvation. His only option was to play for time and hope that Lévis, the new commander, could relieve him. Outside the walls the British guns were silent, but their grim determination was evident, as they could be seen setting up batteries and redoubts within 1,000 yards of the weak and feeble western wall. Soon Ramezay was beset by a clamour, even from the militiamen whom he hoped would defend the city, that he should surrender immediately.

On 17 September Lévis arrived at the Jacques Cartier river and took command of the stricken French army. He at once decided that the retreat had been an egregious error and browbeat Vaudreuil into marching the army back to Quebec. Lévis’s idea was that they do everything possible to prevent the fall of Quebec but that, if the city proved indefensible, they should raze it to the ground before abandoning it so that the incoming British would inherit a mere blazing shell of a town. Unfortunately for him, it took a further twenty-four hours to get the army properly supplied and on the road. In this crucial time-lapse Ramezay’s nerve had given way, beset as he was both by defeatism within and the evidence of British determination without; it was obvious from the disposition of the Royal Navy warships that they intended to blow apart the Lower Town while Townshend’s batteries pulverised Upper Quebec. In a further comedy of errors, Vaudreuil sent urgent despatches to Ramezay telling him to hold out at all costs, but the mounted courier managed to lose them on the road to Quebec. When contact was finally made by a cavalry detachment on the night of 17–18 September, a rueful Ramezay told them they were too late. He had offered Vaudreuils terms of capitulation to Townshend and they had been accepted.

The surrender terms were formally signed in Townshend’s tent on the morning of the 18th. The garrison was to be allowed the honours of war and was to be embarked for France as soon as possible. The property rights of the Québécois and their Catholic religion would be respected and full safeguards offered to all luminaries and dignitaries of Quebec society. To an extent the accord was an embarrassment to both sides. Ramezay felt a fool when he realised Lévis was marching to his aid, but said he had known nothing of this and meanwhile had yielded to the pleas and imprecations of people who were starving. Besides the fault, if any, lay with Vaudreuil, who had left behind such explicit instructions and such a carefully drafted surrender document. Townshend, too, foresaw that he would be criticised for leniency, and pointed out that both the approach of winter and the persistence of Lévis made his position precarious. Any kind of protracted siege would expose him both to attack in the rear and, more pertinently, to the ravages of winter. A winter investment of Quebec would be madness and for the fleet to tarry any longer would mean that it would either be iced up in the St Lawrence or struggling back across the Atlantic in the teeth of full winter gales. He need not have worried: his ‘leniency’ was condoned in the euphoria of victory; it was Ramezay who took the full weight of opprobrium in Paris, not the Machiavellian Vaudreuil, who should have been held responsible.

The first British troops entered Quebec on the evening of the 18th. Townshend was as good as his word: there were no reprisals, no looting, no atrocities. He knew that it was vital to secure the cooperation of a civilian population that could not be held down indefinitely by force, especially since Lévis would probably return in the spring with heavy artillery and siege impedimenta. From the French point of view, the British occupation of Quebec even had some advantages for, on the Jacques Cartier river, their army was free from worries over food supplies and meanwhile, in Quebec, the relief of a famished population was a British problem which would further drain their resources. Townshend now saw himself in a race against the winter and set sail at once for England. Since Monkton had to journey to New York for urgent medical treatment, Murray was left in Quebec for the winter as Governor and military commander. Most of the troops stayed with him, but the navy withdrew on the 26th, heading for winter anchorage at Halifax and intending to return in the ice-free spring of 1760. The bitterly disappointed Lévis withdrew to the Jacques Cartier river and built a fort ready for the following year’s campaign. Vaudreuil decamped to Montreal, where he spent his time composing further mendacious apologias and blame-shifting memoranda. He consoled himself with the thought that he had at least fulfilled Belle-Isle’s minimum requirements and had retained a foothold in the New World until 1760. It remained to be seen whether the French Minister of War could perform a miracle and pull some unexpected rabbit out of his conjuror’s hat.

The taking of Quebec was probably the most spectacular success in the year of victories and certainly had the most momentous consequences. From this exploit has arisen the legend of Wolfe as, even more than Clive of India, the true begetter of the first British Empire. Seldom has historical inevitability been more blatantly confused with the contingent, the adventitious and the aleatory. For the truth is that Wolfe was above all almost supernaturally lucky. The landing at l’Anse au Foulon was, objectively considered, a foolish gamble rather than an act of military genius. It presupposed the unlikely concatenation of a string of separate French errors. The most scholarly study of Quebec in 1759, by C. P. Stacey, lays the blame mainly at Bougainville’s door:

Bougainville botched the task of guarding the area above Quebec. He failed to ensure that the posts nearest to the city were fully watchful; he failed to provide adequate communication from those posts to the Beauport camp and his own headquarters; he failed to see to it that the posts were warned of the cancellation of the movement of the provision boats on the fatal night of 12–13 September; finally he failed to observe what was happening and to march to counter Wolfe’s action, with the consequence that Wolfe landed without difficulty and Bougainville himself was too late to cooperate with his chief on the Plains of Abraham at the critical moment the following morning. His inefficiency had much to do with the French disaster.

Later generations might point out that Wolfe, for all his brilliance as a tactician, was a poor strategist; that his brigadiers’ plan to land the army at Cap Rouge and cut the St Lawrence in two was a much sounder basis for action than the gambler’s landing at l’Anse au Foulon. But in the late autumn of 1759 all most people perceived was the well-nigh incredible fact of his heroic victory. The English-speaking colonies went wild, with pealing bells, bonfires and illuminated windows lighting up all the great cities of the eastern seaboard, from Boston through New York to Philadelphia. Yet even these celabrations were dwarfed by the effusions of joy that hit London in late October when news of Wolfe’s triumph finally arrived. Elite opinion, fuelled by Wolfe’s pessimistic despatches, had given up on Canada and accepted that there would be no progress until 1760. The always gloomy Duke of Newcastle wrote to his henchman Earl Hardwicke on 15 October in particularly despondent fashion. Picking up on the phrase about ‘without any prospect’ in Wolfe’s last letter to London, the acidulous Horace Walpole commented: ‘In the most artful terms that could be framed he left the nation uncertain whether he meant to prepare an excuse for desisting or to claim the melancholy merit of having sacrificed himself without a prospect of success.’ But when Pitt read Townshend’s account of the Canadian triumph he and the city of London with him went overboard in an outpouring of frenzied joy that reads from contemporary accounts as if it were collective hysteria. Bumpers were raised, cannon fired, huzzas shouted, bells pealed, beacons lit and bonfires lit on every patch of green or common. The fact that Wolfe had died in the very moment of victory appealed as much to the English ruling elite and middle classes as it would to their similarly sentimental Victorian counterparts.

Horace Walpole, quickly changing his tune, argued that the taking of Quebec was stranger than fiction and a mythic event that outstripped anything that had come down from the ancient legends of Greece and Rome. Not even Pitt’s eloquent oratory, he thought, so much in evidence in his triumphalist speech to the House of Commons on 21 October, could do justice to the occasion:

The incidents of dramatic fiction could not be conducted with more address to lead an audience from despondency to sudden exaltation than accident prepared to excite the passions of a whole people. They despaired, they triumphed, and they wept, for Wolfe had fallen in the hour of victory . . . [Pitt’s attempts to find] parallels . . . from Greek and Roman history did but flatten the pathetic of the topic . . . The horror of the night, the precipice scaled by Wolfe, the empire he with a handful of men added to England, and the glorious catastrophe of contentedly terminating life where his fame began – ancient history may be ransacked, and ostentatious philosophy thrown into the account, before an episode can be found to rank with Wolfe’s.

Yet the universal British ecstasy overlooked one inconvenient fact. The French had been worsted in North America but in Europe they still posed a clear and present danger to the island empire.