It will already be clear that 1759 was a good year for literature. Apart from the classics that have endured, there was a host of now forgotten works that made an impact in their day. To take the example of Britain alone the Scots cleric Alexander Gerard made what was then considered an important contribution to aesthetics and the debate about the sublime in his An Essay on Taste, while the English clergyman Richard Hurd in his Moral and Political Dialogues, using the conceit of quizzing literary figures from the past on various subjects, was taken seriously at the time, even though for posterity he was totally eclipsed by Hume and his Essays Moral and Political. Sarah Fielding produced a kind of proto-Gothic novel, The History of the Countess of Dellwyn, in some ways anticipating the motifs that Horace Walpole would make famous five years later in The Castle of Otranto. The Irish actor and dramatist Charles (‘Mad Charlie’) Mack lin was hard at work on two plays, The Married Libertine and Love à la Mode.

Yet another figure almost totally forgotten today was the poet Edward Young, who in 1759 penned his Conjectures on Original Composition – his last significant writing. As with so many other productions of this year, one can almost discern the first shoots of the Romantic movement breaking through. Young was the first to articulate fully the now familiar notion of artist as genius – his work was a case of ‘what oft was thought but ne’er so well expressed’ – and to stress that the author is creative artist, not a mere craftsman with technique. Young popularised the idea of the genius as a kind of transmission belt for divine inspirations – what a later age would call the workings of the unconscious:

Nor are we only ignorant of the dimensions of the human mind in general but even of our own. That a man be scarce less ignorant of his own powers than an oyster of its pearl or a rock of its diamond; that he may possess dormant, unsuspected qualities, till wakened by loud calls, or stung by striking emergencies, is evident from the sudden eruption of some men, out of perfect obscurity, into public admiration, on the strong principle of some animating occasion; not more to the world’s great surprise than their own.

Perhaps the one thing lacking in English literature this year was any first-class poetry, with Pope and Thomson dead, Young declining and the Romantics still some way over the horizon. In 1759 Oliver Goldsmith, whose Deserted Village was still a decade away, was then a hack with aspirations, writing ruefully to his brother in February: ‘Could a man live by it, it were not unpleasant employment to be a poet’ With a background as erratic Trinity College, Dublin, scholar, failed emigrant, failed parson, failed physician, sometime pharmacist’s assistant, amateur flautist, Grub Street hack and now apprenticed and penurious scribbler, Goldsmith hardly seemed destined for fame and fortune. The one quality he did have was energy. In 1759 he not only contributed prolific ally to Smollett’s British Magazine and even founded his own publication The Bee but wrote an angry treatise entitled Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning in Europe, in which he documented the decline of the arts in Europe as a result of a lack of enlightened patronage and the bad influence of dry criticism and academic scholarship. Although critics dismissed it as too short an essay to do justice to its broad ambit, it was undoubtedly fresh, invigorating and convincing when it dealt with the London Grub Street scene.

Goldsmith had seen for himself the bitter disappointment of hungry would-be novelists, the poverty of poets, the slow or non-existent rewards of genius, the mercantile greed and low standards of London publishers and booksellers. He upset David Garrick with his attack on genteel, sentimental comedy – ‘a kind of mulish production with all the defects of its opposite parents and marked with sterility’ – and evinced a delight in epigrams and saws that drew him, inevitably, to the circle of Samuel Johnson. To be ‘dull and dronish’, he observed, was ‘an encroachment on the prerogative of the folio’ and he inveighed particularly at the straitjacket or cul-de-sac into which society forced poetry. ‘Does the poet paint the absurdities of the vulgar, he is low, does he exaggerate the features of folly to render it more ridiculous, he is very low. In short, they have proscribed the comic or satirical muse from every walk but high life, which, though abounding in fools as well as the humblest station, is by no means so fruitful in absurdity.’

The greatest living English poet was Thomas Gray, but his masterpiece had appeared eight years earlier. There are probably more famous tags from his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard – ‘paths of glory’, ‘far from the madding crowd’, ‘wade through slaughter to a throne’, full many a flower is born to blush unseen’, ‘some village Hampden, etc, etc – than from any other poet but Shakespeare. Gray was singularly unlucky in love: his schoolfriend Richard West died young, he was snubbed by fellow homosexual Horace Walpole and spent the last years of his life in a fruitless passion for the young Swiss traveller Charles Victor Bonstetten. Celibate and depressive, Gray was particularly interested in the progress of the Seven Years War and quizzed his friend George Townshend (Wolfe’s deputy) about the campaign in Canada. In January 1760 he reported the result of his conversation to Thomas Wharton: ‘You ask after Quebec. General Townshend says it is much like Richmond-Hill, and the River as fine (but bigger) and the vale as riant, as rich and as well cultivated.’ There is much more evidence of Gray’s interest in military affairs. On 8 August 1759 he commented as follows on the Battle of Minden:

The season for triumph is at last come; I mean for our Allies, for it will be long enough before we shall have reason to exult in any great action of our own and therefore as usual we are proud for our neighbours. Contades’ great army is entirely defeated: this I am told is undoubted, but no particulars are known yet; and almost as few of the other victory over the Russians, which is lost in the splendour of this great action.

Yet there are even more intimate links binding Gray to the world of military action, for possibly the best-known story about General Wolfe at Quebec involves the Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. John Robison, later Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University, was in 1759 a young midshipman on the Royal William. He told Robert Southey (who passed it on to Sir Walter Scott) that on the night of 12 September during the British army’s night passage on the St Lawrence, Wolfe pulled a copy of Gray’s works from his pocket and began declaiming the Elegy. When the reading was received in silence by his officers, Wolfe upbraided them: T can only say, gentlemen, that if the choice were mine, I would rather be the author of these verses than win the battle which we are to fight tomorrow morning.’ In another version of the story, one of Robison’s students, James Lurie, remembered the Professor saying that someone else recited the Elegy from memory and that Wolfe then said: ‘I would rather have been the author of that piece than beat the French tomorrow’ – a giveaway remark that led the company to infer that there would be a battle next day, since Wolfe had so far confided in no one. The story became widely known after William Hazlitt repeated it in the Literary Examiner in 1823. The severest, most straitlaced scholars have always affected to disbelieve the story, on three main grounds: there is no mention of this anecdote in eighteenth-century literature; it does not fit what we know of the character and personality of Wolfe; and lines like those about the flower blushing unseen and wasting ‘its sweetness on the desert air’ scarcely square with the mentality of a self-publicist. But it is known that Wolfe’s fiancée Katharine Lawler had given him a copy of Gray’s poems just before he left England. The consensus is that the story is probably true in its main outline. The prime irony was that Gray never knew that one of Britain s great military heroes had made this most famous tribute to his most famous poem.

Cast down and depressed by the debacle at Montmorency, Wolfe contemplated the likelihood that he would soon have to depart for Louisbourg, Halifax or even London, leaving a holding force on the île-aux-Coudres against his return with another army in the spring of 1760. But his anger with the French found expression in a third proclamation in early August (the first had been on 27 June) which made it clear that, since they had spurned his earlier offer of amnesty, the full fury of war would now be visited on them. The Canadians, he alleged, ‘had made such ungrateful returns in practising the most unchristian barbarities against his troops on all occasions, he could no longer refrain in justice to himself and his army from chastising them as they deserved’. What particularly infuriated Wolfe was the behaviour of Montcalm’s Indians, particularly the Ottawas and Micmacs, and their habit of scalping and mutilating prisoners or the sentries they often overpowered in the darkness in the remote British outposts. There were suspicions, too, that the French Canadians did their own scalping and mutilating and passed it off as the work of their benighted Indian allies, whom ‘unfortunately’ they could not control. But when Wolfe officially remonstrated to Vaudreuil, the Governor gave him short shrift. Since both sides had always used Indians as allies in their struggle for mastery in North America, it was arrant humbug for the British to raise the issue now just because Wolfe had scarcely a native man in his ranks. Indian atrocities, though regrettable, were part of the ‘fortunes of war’ that both sides had to suffer stoically in this increasingly bitter conflict.

It may be that Wolfe had the Indians particularly on his mind at this juncture through an association of ideas with another enemy. By the beginning of August his relations with Townshend had deteriorated alarmingly, but meanwhile Townshend had added to his portraiture portfolio by proving the first authentic sketch of an Ottawa warrior in full fighting fig. In the small hours of 8 August 1759 this brave swam the ford below Montmorency Falls, making landfall where he hoped to pick off an unwary British sentry. But luck was against him; the Ottawa found himself staring down the muzzle of a redcoat’s musket; within minutes the warrior was hauled before Brigadier Townshend. The Indian pretended not to understand anything said to him, even though there were many in the encampment who spoke the Ottawa tongue. Regarding with aristocratic hauteur ‘a very savage looking brute and naked all to an arse clout’, Townshend was sufficiently intrigued to make a quick sketch of his prisoner. This initial sketch became the first of a series of watercolours that Townshend completed during the campaign – invaluable as the only known images of North American Indians produced by an eyewitness during the Seven Years War. The would-be scalper was manacled and stowed on board a British warship, with the intention that he should be taken back to England as a present for George II, but the nimble Ottawa slipped his chains a few nights later and slid into the dark waters of the St Lawrence. Search parties were launched but no trace of the escapee was found, and the natural inference is that such an intrepid swimmer made his way safely back to the French lines.

According to Wolfe’s interpretation of the rules of war, the French use of Indians and the masking of their own atrocities as the uncontrollable actions of the painted savages gave him the justification he needed to harry the inhabitants of the St Lawrence with fire and sword. Although he had given the Canadians until 10 August to change their ways, he decided to get his reprisals in first and on 4 August sent a company of Rangers to put the settlement of St Paul’s Bay to the torch on the ground that the people there had fired on British boats. The man he chose to lead the group – one of Rogers’ Rangers named Joseph Gorham – was an Indian-hating fire-eater who went about his work with a relish that Wolfe would have recognised from his time in Scotland with Cumberland and ‘Hangman Hawley’. Wolfe’s standing order of 27 July prohibited the Rangers from scalping (one of the Indian customs they had taken over with avidity, unless the enemy comprised Indians or Canadians dressed as Indians). But the Rangers simply scalped whomever they pleased, then claimed that the enemy had been ‘masquerading’ as Ottawas. Two days later Wolfe told Monkton that if any further shots were fired at his boats, he intended to burn every single house in the village of St Joachim, although ‘churches must be spared – I shall give notice to Vaudreuil obliquely, that such is my intention’. The scorched-earth policy is a measure of Wolfe’s desperation, for he clearly hoped that a reign of terror would force the French out of their entrenchments to defend their own kith and kin. Civilians in the St Lawrence were caught in a horrible dilemma: Vaudreuil had already warned them that if they collaborated with the enemy, he would unleash his Indians against them, and now here was Wolfe warning that if they did not collaborate, he would burn hearth and home down around their heads.

After gutting Baie St Paule, Gorham and his marauders moved on to Malbaie (Murray Bay) where he burned down forty houses and barns, then crossed the river to Ste Anne de la Pocatière, where he torched fifty more. Throughout August the sky over the St Lawrence was blackened as if by a mighty forest fire, as smoke from burning farmhouses blotted out the sun. On both sides of the river the inferno raged, as Gorham’s Rangers fired every sign of human civilisation. By the middle of the month they had completed the destruction of all houses, farms and barns between the Etchemin river and la Chaudière. On the 23rd it was the turn of the villages on the north shore between Montmorency and St Joachim to taste the pyromania of Wolfe’s arsonists. The Ile d’Orléans was swept into the conflagration. At the beginning of September Major George Scott, commanding a mixed force of regulars, Rangers and seamen, proceeded downriver and began destroying all buildings, flocks and harvests on the south shore, following Wolfe’s threat to ‘burn all the country from Camarasca to the Point of Levy’. In a fifty-two-mile march, Scott and his destroyers burned 998 buildings (Scott kept a precise count), took fifteen prisoners and killed five Canadians for the loss of two killed and a handful wounded. The final tally of destruction in Wolfe’s campaign of terror was more than 1,400 farmhouses which, a New England newspaper gloatingly reported, it would take half a century to rebuild. Nor was this all. British sources kept quiet about the accompanying atrocities but the modern historian Fred Anderson sums up with terse under-statement: ‘No one ever reckoned the numbers of rapes, scalpings, thefts and casual murders perpetrated during this month of bloody terror.’

The terror tactics were probably counter-productive as they solved the Canadians’ dilemma for them. They now had little choice but to oppose the British, since Wolfe allowed them no way out. Ferocious guerrilla warfare was the inevitable upshot, with particularly bitter fighting on the north shore below Montmorency. The principal guerrilla leader was a priest named Portneuf, whom the sources confusingly refer to as both the Abbé de Beaupré and the Curé de St Joachim. Evidently a confidant ofVaudreuil, Father Portneuf tried to mitigate the worst savagery in the guerrilla warfare and deal with the British officers opposing him in a civilised way. His chivalry and gallantry were brusquely rebuffed by officers who were under orders from Wolfe to wage war to the knife. Frustrated at the priest’s able defence, Wolfe sent reinforcements to the north shore and on 23 August 300 fresh troops and field artillery arrived on the scene. A ferocious artillery barrage on Portneuf’s position at Ste Anne drove the defenders into the open, where they were butchered mercilessly. Thirty men and Portneuf himself were killed and scalped; the British used the lame excuse that the defenders had disguised themselves as Indians. No quarter was given or prisoners taken. Ensign Malcolm Fraser of the Highlanders had already promised two of the men their lives but he was overruled by the bloodthirsty local commander Captain Alexander Montgomery, who ordered all captives slaughtered in cold blood. Montgomery celebrated his hecatomb of Portneuf’s guerrillas by gutting all the houses in Ste Anne and gratuitously reducing the Château Richer to ashes.

Wolfe had once again proved himself an able disciple of Cumberland. In Tacitus’s words he had created a desert and called it peace. Even Townshend, no bleeding heart, was revolted and wrote to his wife: ‘I never served so disagreeable a campaign as this. Our unequal force has reduced our operations to a scene of skirmishing, cruelty and devastation. It is war of the worst shape. A scene I ought not to be in, for the future believe me, my dear Charlotte, I will seek the reverse of it.’

Wolfe’s apologists, beginning with the intellectually dishonest Parkman, claim that his scorched-earth policy and his massacres were simply tit-for-tat retaliation for far worse war crimes meted out by Vaudreuil, Montcalm and their allies. This is scarcely convincing. The atrocities committed on the French side, as at Fort William Henry in 1757 and elsewhere, were the results of French inability to control their Indian allies, on whom they were forced to depend because of the massive superiority in numbers enjoyed by the British. There was no general guerre à outrance order of the kind that Wolfe issued in August and it is quite clear that his orders were regarded as egregious or received with stupefaction. Quite apart from the disgust evinced by those such as Malcolm Fraser and Townshend, there is Monkton’s querying of Wolfe’s draconian instructions and the British government’s censoring of Wolfe’s despatch to Pitt on the subject. The most that can be said in Wolfe’s defence is that warfare in North America in the eighteenth century was always a nasty and barbarous business. But is it not a logical implication of that, as Wolfe’s defenders seem to think, to accept that atrocity and barbarity should therefore be raised exponentially to new heights. If the Indians were benighted savages, what was it that justified supposedly civilised European officers behaving with equal savagery? Moreover, as was famously said of Napoleon’s murder of the Due d’Enghien, it was more than a crime, it was an error. Wolfe’s atrocities did nothing to advance his ultimate aims, since the Québécois could no more be drawn out by the sufferings of their compatriots than by the ‘strategic bombing’ of their fair city.

While this cruel devastation of the Quebec hinterland went on, Wolfe probed the area of the St Lawrence above the city for some foothold or landing place, trying also to make contact with Amherst and cut Montcalm’s communications. Brigadier Murray commanded this venture, and a game of cat and mouse developed with the French, the British making temporary landfall at various points, the French ponderously following them along the shore. Atrocity bade fair to follow Murray upriver for, after a repulse on the northern shore by Bougainville on 8 August, which cost the invaders 140 men killed and wounded, Murray switched to St Antoine on the southern shore, where he threatened to raze every dwelling to the ground if the inhabitants opened fire on him. On 18 August he re-embarked, gave Bougainville the slip, landed at Deschambault farther upriver on the northern shore and destroyed Montcalm’s spare baggage and equipment.

This raid was sufficiently worrying to Montcalm to draw him temporarily from Quebec. Fearing that his communications would be cut, he rushed to Bougainville’s assistance, only to learn that the British had already withdrawn. Montcalm confessed himself relieved, for if Murray had established a bridgehead in force at Deschambault, he lacked the forces to dislodge him. But he worried about the shape of possible similar things to come, unlike the bone-headed Vaudreuil, who could see no point in Montcalm’s sortie and thought he was merely panicking. The August probe upriver stuttered out in stalemate: Montcalm returned to Beauport and Murray to Point Levis, summoned back post-haste by an increasingly jumpy Wolfe. But Murray came back with something of infinite value: news that Fort Niagara had fallen and the would-be French counterattack beaten off. When Montcalm received this intelligence, he was justifiably alarmed and sent off the Chevalier de Lévis and 800 troops to reinforce the crumbling western theatre. These were men he could ill afford to spare for, as it was, defending a front that extended from the Montmorency Falls to the northern shore of the St Lawrence upriver from Quebec, he was stretched almost to snapping point even before he detached Levis.

Wolfe, unaware of Montcalm’s grave concerns, was himself undergoing a crisis in August, and perhaps we can understand the atrocities of that month as the fanatical actions of a man who had essentially lost sight of his aim. His problems were twofold: he was ill and he was at odds with his brigadiers. For most of August he was scarcely well enough to leave his sick-bed. Barely recovered from a grave attack of fever, he suffered from a steadily worsening tubercular cough and was weak from the constant blood-letting to which his physicians subjected him. High on opium and other painkillers, he could often not even urinate without terrible pain. Situated thus, he was scarcely able to deal with the accumulated hostility of all three of his brigadiers.

Wolfe had got off on the wrong foot with Townshend – admittedly not a difficult thing to do – and the cryptic diary evidence for 7 July indicates that there had been a stand-up row between the foppish aristocrat and his commander, with Townshend threatening to foment a ‘parliamentary inquiry’ into the behaviour of his commanding officer. There was further tension during the rest of July, and it seems clear that Wolfe gradually alienated Murray also during this period. The commander lost face considerably as a result of the Montmorency fiasco on 31 July, after which we find Deputy Quartermaster General Guy Carleton, previously a Wolfe favourite, joining the dissenters. Then, in the middle of August, Wolfe additionally fell foul of Monkton. The details are obscure, but on 15 August we find Wolfe apologising with ‘hearty excuses’ for any unintentional offence offered when the commander withdrew men from Monkton’s posts and thus weakened them. On 16 August Wolfe wrote again almost pleadingly to Monkton, saying: ‘I heartily beg you forgiveness.’ Captain Thomas Bell, whose diary is an important source for the Quebec campaign, relates that Wolfe destroyed his diary for the period after August but that this deleted section ‘contained a careful account of the officers’ ignoble conduct towards him in case of a Parliamentary enquiry’.

It was 27 August before Wolfe felt well enough to convene a council of war with the three brigadiers he had so seriously alienated. Wolfe almost certainly had no great opinion of their strategic abilities but consulted them, partly because such a council was a cultural norm in eighteenth-century military life and partly so that he could not later (maybe in a parliamentary inquiry?) be accused of having acted in a high-handed and authoritarian way. The council took place on 28 August. Wolfe began by outlining three possible courses of action, all of them involving an attack on the Beauport lines. The first idea was to catch the French forces between two fires, with both a frontal attack and an attack in the rear by a large force which would have crossed the Montmorency by the upper ford. The second was essentially a rerun of 31 July, with an attempt being made once more to recapture the upper redoubt, with Townshend’s men establishing a beachhead and Monkton’s crossing from Point Levis for the coup de grâce. The third was essentially a combination of the first and second scenarios. All the proposed actions were in effect simply variations on the old strategy that had failed so dismally on 31 August.

Wolfe’s apologists, anxious to rescue him from the obvious charge of bankruptcy of ideas, allege that he was simply ‘flying a kite’, that he had already decided on an alternative strategy but was determined to get his brigadiers to commit themselves in writing to a final rejection of all attacks on the Beauport front. The alternate and much more likely explanation is that Wolfe simply had no idea what to do next. Whatever the reason for his spectacularly unimaginative memorandum, it is certain that his brigadiers rejected it decisively. They suggested instead that Wolfe abandon all idea of forcing the Beauport-Montomorency front and concentrate instead on finding somewhere upriver to land the next blow. This would threaten Montcalm’s food supplies from the west and finally force him to emerge from his entrenched eyrie in Quebec. Landing at some location above Quebec would have the further advantage that the British army could concentrate, instead of, as hitherto, being vulnerable to French local superiority. Crucially, if defeated at Quebec, Montcalm would no longer have the option of being able to retreat west and continue the struggle there; the battle for Quebec would, under the new dispositions, settle the entire struggle for mastery in North America.

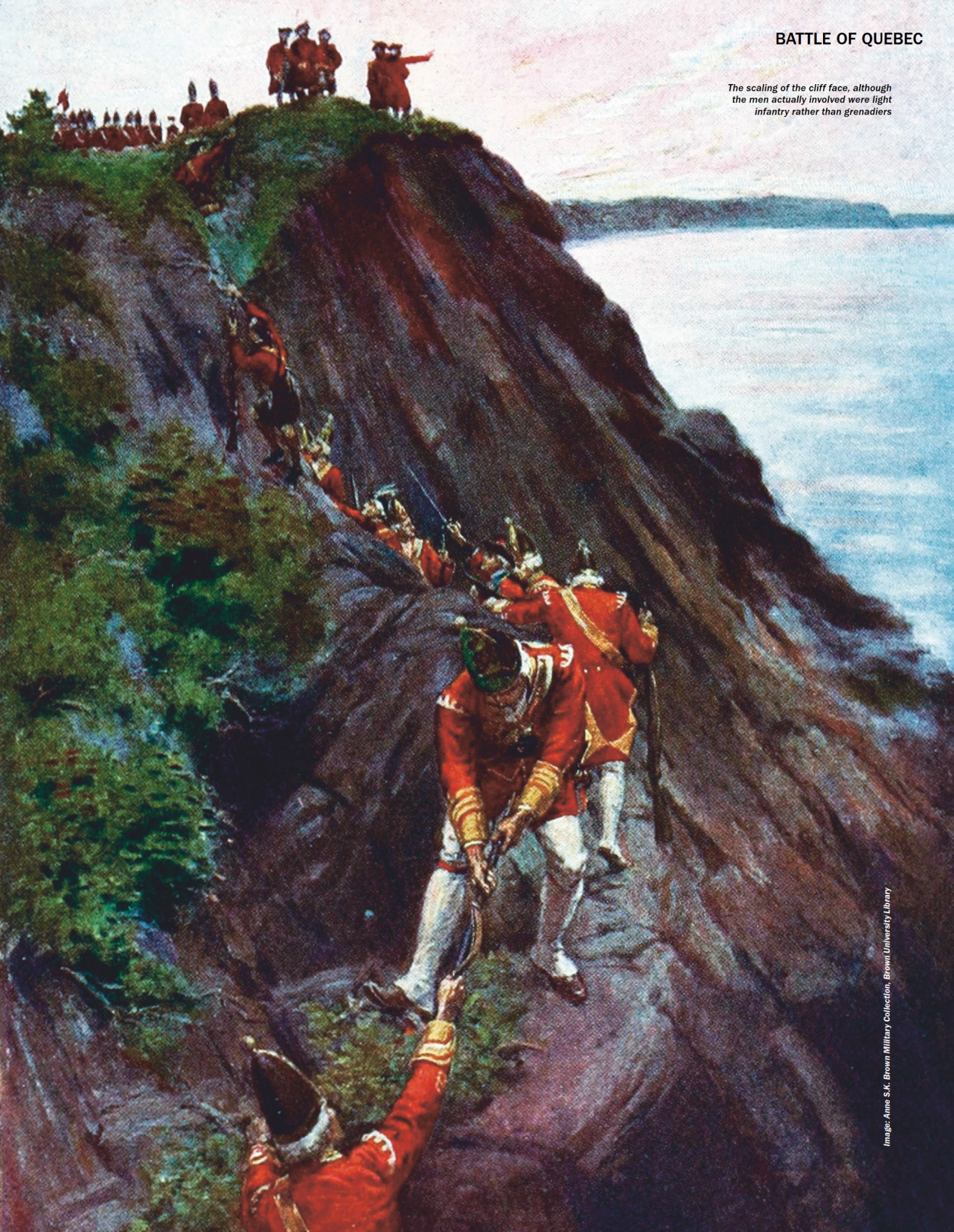

By the beginning of September the British had assembled a formidable naval force in the river above Quebec. On 28 August the frigate Lowestoft, the sloop Hunter and smaller vessels managed to slip past the French shore batteries and join the handful of ships already upriver. On the night of 31 August-i September five more vessels, including the frigate Seahorse, forced passage above Quebec. Wolfe thus had covering fire for any force he tried to land to the south-west of the city (i.e. upriver). His brigadiers now took in hand a skilful evacuation of the Montmorency camp, transporting the troops first of all to the Île d’Orléans. Leaving a holding force on that island to protect the base camp, hospital and stores, and another strong garrison on Point Lévis, where all the heaviest artillery was stationed, the British commanders conveyed the entire besieging army to the mouth of the Etchemin river on the south bank (south-west of Point Levis), ready for the eventual move upriver. The evacuation was another great success for amphibious operations. Monkton feinted towards the right of the French defences by the mouth of the St Charles river, while Wolfe dragged his feet about the final withdrawal of men from Montmorency, keeping five battalions there until 3 September in the hope of tempting the French commander to a rash sortie. Montcalm could not be tempted, but many observers on both sides thought he had lost a great opportunity to sow chaos during the intricate process of embarkation.

Both commanders had their problems. Wolfe was not sanguine about the outcome of the new strategy and confessed to Pitt that he had acquiesced in it with great misgivings. In his last letter to his mother, written on 31 August, Wolfe was equally pessimistic:

My antagonist has wisely shut himself up in inaccessible entrenchments, so that I can’t get at him without spilling a torrent of blood and that perhaps to little purpose. The Marquis de Montcalm is at the head of a great number of bad soldiers, and I am at the head of a small number of good ones, that wish for nothing so much as to fight him – but the wary old fellow avoids an action doubtful of the behaviour of his army.

In his last letter to Pitt, dated 2 September, Wolfe complained about the difficulty of campaigning in Canada where the terrain was against him and the St Lawrence river itself attenuated his superiority in numbers and matériel. He also stressed the growing casualty roster: since the end of June he had lost 850 men dead and wounded, including two colonels, two majors, nineteen captains and thirty-four subalterns, and now there were signs that disease too was lending a hand, further reducing his effective manpower. Wolfe admitted that he had only grudgingly accepted his brigadiers’ plan to cut Montcalm’s line of communications between the Jacques Carrier and Cap Rouge rivers and the subtext of all his final messages indicated a man preparing for ultimate failure, half-accepting his responsibility for this and half-wishing to slough it off onto others – though, to be fair, when he tried to blame the navy for some of the setbacks and Admiral Saunders vociferously objected, Wolfe agreed to remove the offending words. Referring to the debacle of 31 July, Wolfe even displayed magnanimity, for his letter to Saunders reads as follows: ‘I am sensible of my own errors in the course of the campaign; see clearly wherein I have been deficient, and think a little more or less blame, to a man that must necessarily be ruined, of little or no consequence.’