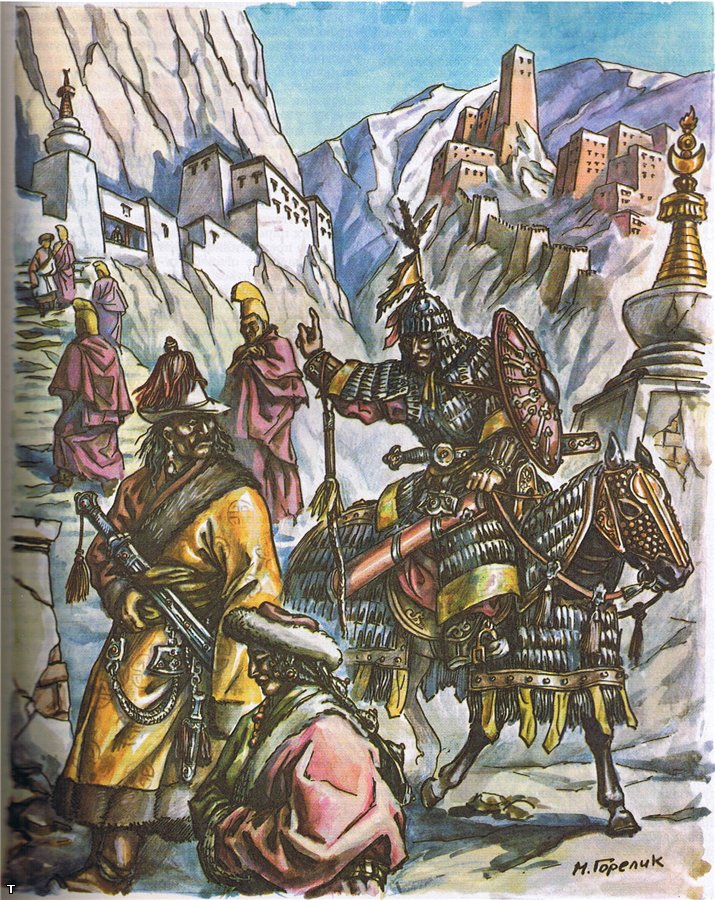

About 560 AD a local Tibetan chieftain, Gnam-ri slon mtshan, revolted against his Zan-Zun overlords and established the Yarlung dynasty. By about 630 his successor Sron btsan sgampo had unified the Tibetan clans and founded an empire which over the next two centuries fought expansionist wars. After 841 this broke up, but successor states survived and continued to maintain armies, often fighting each other. The last Yarlung ruler was Rgyal-sras of Tsong-kha, a principality on the border of the Hsi-Hsia state, who died in 1065. Arabs, Chinese and Bengalis were all at various times associated with the Tibetan empire: Tibetan armies in India and west of the Parnirs seem to have been small, and their Ferghanan allies are best regarded as Turks rather than Arabs. Combined Tibetan-Chinese armies were usually under Chinese command. The Abbasid troops represent hose captured by the T’ang in 801 thought to have been either taken prisoner by the Tibetans in an otherwise unknown western campaign and incorporated into the army, or failed rebels or dissidents who had voluntarily joined it They were under Tibetan command. Nepalese and Nan-chao allies cannot be used with each other, nor with any other allies apart from Ch’iang. The exact nature of Nepalese troops is conjectural, but they are described as cavalry. They could be a large majority of a Tibetan-Nepalese force. Tibetan cavalry are described in the T’ang Annals as armed with very long lance, both man and horse completely mailed except for the eyes, and invulnerable to swords and strong bows There is no suggestion anywhere that they charged at the gallop. The same T’ang source describes them as fighting dismounted and arrayed in ranks, therefore can always dismount; though bow-armed they favoured close combat, so dismount as Spear-armrd troops. Tibetans were skilled makers of siege equipment

Tibet Appears, 600–700

One day in the winter of 763, the unthinkable happened to China’s great Tang empire. A victorious enemy army rode through the streets of the imperial capital, Chang’an. These were the Tibetans, a people of whom, barely a century earlier, most Chinese hadn’t even heard. The city of Chang’an was not only home to the emperor and his court – it was a capital of culture famous throughout Asia, its streets thronging with merchants, musicians, monks and officials going about their daily business. It was the prerogative of the Chinese emperor to look down upon everything outside his realm as barbaric, and here in Chang’an one could perhaps forgive him for doing so.

Yet the Tibetan conquest was no simple barbarian onslaught. The Tibetans had first lured the Chinese general Tzuyi and his army out of Chang’an to fight them in the western provinces. Then suddenly, and too late, the Chinese had realised that allies of the Tibetans were marching on Chang’an from the east as well. The emperor fled, leaving the city stripped of both its army and its imperial court. The Tibetans now had a window of opportunity to seize the city before the return of the Chinese army. That window was opened by a rebellious faction at the Chinese court who had gone over to the Tibetan side. A Chinese rebel opened up the city gates and the Tibetans walked into the capital unopposed.

The Tibetan general leading the army had no ambition to set up a Tibetan government in Chang’an. Instead, he rewarded the Chinese rebels by placing their leader, the prince of Kuangwu, on the imperial throne. In a matter of days the new emperor had appointed a new government and declared a new dynasty. Meanwhile, totally demoralised by the cowardice of the previous emperor, the Chinese army simply fell apart. The situation looked dire for the dethroned emperor who, as the Chinese historians put it, was left ‘toiling in the dust’, while the imperial army had broken up into armed bands that were roaming and pillaging the countryside.

It turned out that the Tibetans had no desire to try to put this chaos in order: no desire, in other words, to rule China itself. Having put their puppet emperor on the throne, they left the city. Some say that they heard rumours of a vast Chinese army advancing from the south. The general Tzuyi was indeed approaching, but at the head of a ragtag army numbering only a thousand or so. When he came to Chang’an he found only a remnant of the Tibetan army still there, and a rather frightened puppet emperor on the throne. Since Tzuyi’s army was so unimpressive he decided to enter the city beating a drum to let the citizens of Chang’an know that the old order had been restored. Soon afterwards the Tang emperor returned, his empire much reduced. Though they may have had no taste to rule from the imperial throne, the Tibetans set their border only a few hundred miles to the west of the capital and forced the Chinese emperor into a series of peace treaties that cut China off from the West.

How did the Tibetans come to pose such a threat to China? To find out, we must go back a century to the time when a king calling himself ‘Son of the Gods’ had managed to harness the power of Tibet’s warring clans and turn it outwards. This explosion of energy overwhelmed everything in its way: and so Tibet appeared. At its centre was the Divine Son, a man with the glamour of a deity, Songtsen Gampo.

Prince Songtsen was born into destiny. Surrounded by ritual from the moment of his birth, he was raised to fulfil a special role, never in any doubt that he was different from other boys. His father was a great king, and no ordinary king but a tsenpo, the embodiment of the divine in this world. When Songtsen inherited that title from his father, he would also inherit the glamour of the divine that his father embodied, a glamour that was already sweeping all of Tibet before it. If few people had heard of the tsenpo before, Songtsen’s father was changing that as he forged alliances with other clans. He was always willing to use his semi-divine status to meddle in clan struggles while at the same time seeming to rise above them. It was the nature of the tsenpo to be of this world and beyond it at the same time.

Throughout his childhood, Songtsen was told his family history. The first of the tsenpos, it was said, came down from heaven via the local sacred mountain. Like rain falling from the sky, he enriched the earth. Local chiefs bowed down before him, for his fate was to rule over them. The first tsenpos were essentially gods among men. During their tenure on earth, the connection to heaven was always there, a ‘sky cord’ made of light leading from the top of their heads up into the beyond. The indignity of death was not for them. Instead, at the appointed time, they ascended back to heaven on the sky cord. Still, Songtsen knew that his family had fallen somewhat since the age of these noble ancestors. They sky cord was gone, squandered by a more recent tsenpo called Drigum.

It seems that Drigum had been a troublemaker who got involved in pointless feuds with his subjects and constantly challenged them to duels – hardly fair considering that he fought with a divine sword forged in heaven. The tsenpo finally met his match when he challenged one of his courtiers to a duel. The courtier agreed, on condition that the tsenpo put aside his magical weapons. At the same time the courtier prepared a trick. He took a hundred oxen and loaded sacks of ashes onto their backs. Then he fixed gold spearheads to their horns. When the duel began, the cattle were loosed, and in the chaos of swirling ash, the courtier killed the tsenpo. Thus the sky cord connection was lost. Drigum’s body was put into a copper coffin and cast into the river.

Nowadays, as Songtsen knew, the tsenpos died like other men; and there were many opportunities for death. Songtsen’s father was not shy of riding into battle at the head of his troops. His divine glamour and personal bravery had won over several clan leaders, extending his domain beyond its humble beginnings in the Yarlung valley in the south of Tibet to encompass much of Central Tibet. These clans were nomads who had migrated from the Central Asian plains to settle down in Tibet’s southern valleys. At the bottom of these valleys were green fields tended by long settled farmers, who had no way to resist their nomadic conquerors. These nomads, as they began to settle, made their homes in tall castles built to withstand sieges on the rocky slopes above those green fields.

How much did the clan leaders really believe in the tsenpo’s divinity? Most likely, they believed when it suited them. The tsenpo was a useful emblem to gather around. Somebody who is, at least in theory, above petty disputes could encourage the clan leaders to set aside their quarrels in pursuit of a greater end, even if that end was only more power. The clan leaders were bound to the tsenpo, and each other, by the most solemn of oaths, sworn beneath the heavenly bodies, before the great mountains, and in the presence of the divine beings of the earth. The oath was carved in stone and sealed with a sacrifice. In practice, though, the clan leaders supported the tsenpo when it served their interests, and conspired against him when that seemed more useful. The history of this Tibetan dynasty is, like that of most dynasties, rife with conspiracy. Rarely did a tsenpo pass away without a violent dispute over the succession; as the new tsenpo was usually just a child, there was ample opportunity for ministers, especially the prime minister, to become the real power behind the throne.

In the direst of situations a clan leader could always retreat to his castle. Only one of the castles from the early era still remains. Yumbu Lhakang stands atop a rocky peak, tall and imposing, its whitewashed walls sloping slightly inwards, windowless at its lower levels but with a four-sided tower to provide views in every direction for miles around. It offers a potent evocation of how perilous life must have been for the early clan leaders. Songtsen’s father’s greatest victory ended in a siege of one of these castles. His toughest rival was Lord Zingpo, a man whose charisma must have matched that of the tsenpos for he was equally good at forging allegiances with other leaders. After many battles and betrayals Zingpo ended up hiding out in his castle. So impregnable were these structures that the tsenpo had to divert a river and flood the castle’s defences to bring about the final defeat of his enemy.

Prince Songtsen was now heir not only to a divine heritage, but to the largest kingdom Tibet had ever seen. Yet it was not to be handed to him on a plate. When Songtsen was just thirteen, his father was poisoned. The parts of his kingdom that had been absorbed from other clan leaders rose up in an insurgency, showing just how much the new Tibetan kingdom needed the unifying figure of the tsenpo. Songtsen knew this. He captured the traitor who had killed his father and executed him, had the insurgency put down and then rode west at the head of his troops to subdue a hostile army harrying the Tibetan border. Still a teenager, he had proved his authority. The destiny of the tsenpos was in safe hands.

At the centre of Songtsen’s kingdom was the town of Rasa. The name meant ‘Walled City’, an apt description of a place that was part town, part fortress. It was perched on the bank of the Kyichu river and had the mighty mountain range of Nyenchen Thanglha soaring above it to the north, separating it from the great elevated plateau known as Changtang, the ‘Northern Plains’. As it grew with the fame and power of the tsenpo, Rasa acquired a new, more dignified name: Lhasa, the ‘Divine City’. The tsenpo’s court, true to nomadic tradition, moved around Central Tibet in great tented encampments, but increasingly Lhasa was becoming the heart of the kingdom.

It is easy to be forced into a corner in Tibet. The pressure of the Indian subcontinent has pushed up some of the highest mountains in the world to wall the Tibetan plateau. To the west, the famously treacherous Karakoram guard the passes into Afghanistan and Ladakh; to the north, the Kunlun hold back the world’s most hostile deserts; to the south and east are the highest mountains of all, the Himalayas. But Songtsen’s kingdom was not only hemmed in by mountains.

Across the Himalayas, the king of Nepal ruled over the prosperous Kathmandu valley, benefiting from the vast number of traders passing through his little kingdom. To the west was another ancient kingdom, Zhangzhung. Its people were not unlike the Tibetans, their rocky castles perched over even more hostile terrain. Still, they boasted not only their own language, but a culture with a distinct Persian flavour, thanks to the close contacts between Zhangzhung and the lands to the west. Finally, towards China there was a confederacy of tribes known as the Azha, who periodically taunted the Chinese with raids into their territories.

The previous tsenpo had been content to forge alliances with these kingdoms, but Songtsen had bigger ambitions. As long as these neighbours were in place, Tibet would remain a small player. Each neighbour was also a gatekeeper behind whom a greater power lay half-concealed. Behind Nepal lay India, ruled by Harsha, one of the greatest kings in Indian history. Behind Zhangzhung lay Persia, home of a rich and ancient culture. And behind Azha lay China, which was just emerging from a long period of turbulence under a new and powerful dynasty, the Tang.

It didn’t take long for Songtsen to kick down the gates. In dealing with Zhangzhung, he first let it seem that he was happy to follow his father’s example. One of the royal princesses was married off to the king of Zhangzhung to seal an alliance: a common practice in Asian diplomacy, in which princesses were political pawns. Union in marriage with a hostile power made family, and families do not attack their own members. That at least was the theory. Tibetan bards sang songs about the princess sent to Zhangzhung. In these songs, she speaks of her new home with touching dismay.

The place that it’s my fate to inhabit

Is this Silver Castle of Khyunglung.

Others say:

‘Seen from outside, it’s cliffs and ravines,

But seen from inside, it’s gold and jewels.’

But when I’m standing in front of it,

It rises up tall and grey.

Perhaps Songtsen saw an opportunity in the princess’s unhappiness. Or perhaps he had intended all along that she would bring down the kingdom of Zhangzhung from within. In any case, a few years after the marriage the Tibetan princess, now a queen, started working as a spy. She sent Songtsen detailed reports of the movements of the king of Zhangzhung and his troops. When the time was right, Songtsen sent an army to ambush the king while he was away from his castle. The plan was wildly successful: the king was killed, and the vast territory of Zhangzhung – all of what became Western Tibet – was swallowed up by Songtsen’s kingdom.

At the same time, Songtsen was also going about securing foreign allies. The opportunity for an alliance with the kingdom of Nepal fell into Songtsen’s hands when King Narendradeva was ousted and fled into exile in Lhasa. Narendradeva and his court remained there for most of the 630s, and the Tibetans learned much from them. During this time Tibet’s oldest Buddhist temple, the Jokhang, was built on the model of a Nepalese temple, with architectural details carved by Nepalese craftsmen. Though it has been much restored and enhanced in the interim, the Jokhang still stands in Lhasa today as a place of pilgrimage for Tibet’s Buddhists. When Narendradeva returned to Nepal at the beginning of the 640s, it was at the head of a Tibetan army, and when he regained his throne it was essentially as a vassal of the Tibetan empire.

And so to the east and China. During the 630s, the newly established Tang dynasty was busy securing its western frontiers, including the troublesome Azha. Songtsen sent an ambassador to the Chinese court in 634, with little effect. Fours years later, and that much bolder, he sent another ambassador to ask for the hand of a Chinese princess. It is a testament to the importance of this mission that the ambassador was Songtsen’s prime minister and general right-hand man, Gar Tongtsen, scion of the ancient clan of Gar. Apparently, Gar was treated politely and his request was still under consideration when a prince of the Azha suddenly appeared and made exactly the same request. Despite its victories elsewhere, Tibet remained an obscure little kingdom in the barbarian south as far as the Chinese court was concerned. The princess was thus promised to the Azha, and Prime Minister Gar was sent home with little ceremony, empty-handed.

This was an affront to Songtsen’s new sense of his own importance. If the Chinese had underestimated the Tibetan empire this time, they would not be allowed to do so again. Songtsen sent his army, now bolstered with troops from Zhangzhung, up towards China to fight the Azha. Victory followed quickly, and the whole region to the northeast of Tibet – today’s Amdo – was absorbed into the Tibetan empire. With his army now stationed right on China’s border, Songtsen’s bargaining power was much greater. No more polite requests: he demanded the princess, threatening to send his army deep into China if he was refused again. The Chinese emperor, still dismissive of this new upstart kingdom, rejected Songtsen’s demands and despatched his army to teach the Tibetans a lesson. The Chinese troops were easily defeated. The emperor would have to revise his opinion of this new threat.

The Chinese emperor, Taizong, was not so different to the Tibetan tsenpo. He was one of history’s great empire-builders, and one of China’s most capable leaders. Since he had been born into a respectable family of warrior horsemen, and his mother’s clan was of Turkish origin, he had a close affinity with the semi-nomadic people who lived to the west of China. Taizong and his father had toppled the previous dynasty, the Sui, and erected their own, which was given the name Tang, on its ruins. For centuries China had been divided between petty kingdoms and short-lived dynasties, most of them founded by nomadic warriors pouring in from the steppes. Many people looked back nostalgically to the Han dynasty, which had once ruled a vast territory from Korea in the east to Kashgar in the west. But the Han had fallen apart nearly four hundred years before. It was only with Taizong that the Han empire was matched, and for that achievement Chinese history remembers him as one of its greatest heroes.

Thanks to his relatively lowly origins, Taizong was practical and – for an emperor – humble. He had little time for the divinations and magical potions that had fascinated many of his predecessors, and he was always willing to take the advice of experienced officials. As was the case with Songtsen in Tibet, his empire-building was a team effort. Nevertheless, he cut an imposing figure at court, tall and intimidating, with a tendency to fly into purple-faced rages. His impressive stature and fearsome temper stood him in good stead with the Tang’s rivals, who were mostly tough warrior people such as the Turks and the Tibetans.

Once Songtsen had made his point by defeating a sizeable Chinese battalion, he pulled his army back and sent Gar to see the Chinese emperor again. The prime minister arrived in Chang’an in 641 laden with treasure to offer as tribute. For any Tibetan, Chang’an would have been both exciting and intimidating. A city of nearly two million inhabitants with countless foreigners passing through, it was one of the most cosmopolitan places on the globe. Turkish princelings, Japanese pilgrims and Jewish merchants rubbed shoulders in the city’s marketplaces where, especially in the disreputable western market, almost anything could be obtained. For the more respectable, there were the festivities held at the city’s many impressive Buddhist monasteries, which brought the Buddhist culture of India right into the heart of China’s empire.

At the Chinese court, distrust of foreigners was mixed with a fascination for the exotic. In particular, a love of all things Turkish permeated the Tang era, resulting in strange sights in Chang’an, such as Chinese women riding through the streets dressed as Turkish horsemen. Taizong’s son, the crown prince, succumbed to Turkomania to such a degree that he went to live in a camp of Turkish tents in the palace grounds, insisted on speaking in Turkish and eating boiled mutton sliced with his own sword in the Turkish manner. At the same time, Taizong’s own standards had started to slip. Initially he had decried the excesses of previous dynasties, but by the 640s he was already beginning to look like a parody of a decadent emperor. A vast and incredibly expensive palace complex was built, but was torn down when Taizong decided that the architect had chosen the wrong location. And officials had started to complain that Taizong had become addicted to the hunting games that were one of the traditional pastimes of Chinese emperors, and as a result was hardly ever seen at court.

Chang’an must have seemed far removed from the rocky castles of Tibet. Foreign ambassadors were met with an intimidating display of courtly ceremony, designed to inspire awe and reverence. They were put up in one of four hostels situated at the city’s four gates, and all of their activities were directed by hosts who also served as spies to the emperor. Ambassadors were ranked in precedence according to how important the emperor thought they were: hence the Tibetans’ unceremonious ousting on the arrival of the Azha embassy last time round.

When the time came for the ambassador to see the emperor himself, an elaborate ceremony was enacted to impress the foreigner and display the superiority of the Tang dynasty. As the ambassador entered the vast imperial hall, he passed five divisions of armed troops dressed in scarlet. Like a character in a play, the visitor had to recite lines in which he offered his country’s tribute as a vassal to the great emperor. The emperor had no need to speak at all, as everything was handled by his officer of protocol.

Nevertheless, Taizong, who had little time for ceremony, questioned Gar personally and was impressed by his clever answers. There is a portrait of Gar at this audience; in it we see a slender middle-aged man with a long thin nose and a light beard, wearing a black headband and dressed in a red and gold robe of Persian design.9 Gar won the emperor’s respect, and was offered the hand of another princess for himself. He showed his skill at diplomacy in turning the emperor’s offer down gracefully. ‘I have a wife in my own country, chosen by my parents,’ he said, ‘and I couldn’t bear to turn her away. What’s more, the tsenpo hasn’t yet seen the princess who is to be his bride, and I, his humble subject, couldn’t presume to be married first.’ Taizong was impressed again, but would not countenance a refusal. So Gar returned to Tibet with two Chinese brides.

If Chinese historians speak highly of Gar, Tibet’s bards sing of his exploits in more colourful fashion. Their stories are entertaining and, if hardly historical, at least show us how affectionately Gar’s resourceful nature was remembered by the Tibetans. According to the bards there were a number of rival suitors for the Chinese princess and Gar had to pass several tests set by the emperor to win her for Songtsen. In one, each of the parties was given a hundred pots of beer, and the emperor promised that the princess would be given to whoever could finish off the beer by noon the next day without spilling any or getting drunk. The other parties, downing huge jugs of beer one after another, got very drunk, vomited and spilled drink everywhere. But Gar issued his men with tiny cups so that they could drink only a little at a time. Thanks to this sensible measure, no beer was spilled and the Tibetans stayed reasonably sober.

The final test was to pick out the princess from a line-up of a hundred ladies. Gar had already become friendly with the Chinese noblewoman who was looking after the Tibetans at their hostel. Now he became even more friendly, eating, drinking and finally sleeping with his hostess. In an intimate moment Gar asked her to describe the princess, but she refused, scared that the princess would use divination to discover who had betrayed her. Gar’s response was ingenious, if a little bizarre. He locked the door of his quarters, and had a large kettle placed on the floor, filled with water and the feathers of rare birds. On top of the kettle he placed a red shield as a lid, and then asked the hostess to sit on the kettle. A clay pot was placed over her head, and a copper pipe inserted into the pot. ‘Give me your description through the tube,’ Gar said, ‘and if anybody ever finds out by divination, they’ll never believe it anyway. So make it a good description.’ His hostess described every feature of the princess’s body and attire, and the next day Gar succeeded in claiming her for the tsenpo.

And so the princess was escorted to Tibet. The marriage ushered in two decades of peace between the Tibetans and the Chinese. It was also an era of cultural exchange in which young Tibetan aristocrats travelled to Chang’an to study in the city’s schools, while Chinese craftsmen skilled in the making of paper and ink were sent to Tibet, where they demonstrated new technology such as silkworms and millstones. According to Chinese historians, once the princess arrived in Lhasa she set to work civilising the Tibetans, convincing the Tibetan nobility to swap their felt and fur clothes for Chinese silk, and to abandon the old practice of painting their faces red. According to Tibetan historians, however, the princess’s greatest contribution was Buddhist in nature. She brought with her a statue of the Buddha, the first to arrive in Tibet, which was placed in a special temple called Ramoche. Later it was moved to the other Buddhist temple, the Jokhang, where it remains to this day.

Elsewhere in Lhasa there is a statue of Songtsen, flanked by his Chinese princess on one side and a (perhaps legendary) Nepalese princess on the other. For later Tibetans, it was these princesses, their introduction of Buddhist statues to Tibet, and their encouragement of the tsenpo in building Buddhist temples that became the defining images of Songtsen’s rule. At the time, though, neither Songtsen nor his courties are likely to have perceived things in this way. Of the tsenpo’s many consorts, it was one of his Tibetan wives who provided him with his heir. Buddhism, for the time being, was only one of many new cultural imports circulating in Tibet.

Tibetans are quite self-deprecating when it comes to their ancestors. Referring to the time before they were softened by the civilising effects of the Buddhist teachings, they call their forebears ‘red-faced barbarians’. This is a reference to the ancient practice – still seen today among the remaining nomads of Western Tibet – of painting one’s face with red pigment. Even the origin myth of the Tibetan people is a bit rough and ready. In the far-distant past a monkey mated with an ogress, and their offspring were six monkey children. The monkey father took the children to a forest, where they could live on the fruit of the trees, and left them there. After three years, the parents returned and found to their surprise that the monkey children had drastically increased in number from six to five hundred, and eaten the forest bare. Lifting up their arms, the five hundred little monkeys moaned: ‘Mother, Father, what can we eat?’ Their monkey father, at a loss, prayed to the compassionate Buddhist deity Avalokiteshvara, who scattered grain upon the ground. The grain grew into crops, which the father handed over to his many children.

Thus the first Tibetans thrived on the crops that were to become the staples of the Tibetan diet. They grew, and over time their tails shortened, their body hair reduced, they learned to speak and ultimately became humans. It might be a stretch to claim that this is an early version of the theory of evolution, but the legend does assert a kind of genetic legacy from these first parents. It states that Tibetans can be divided into two types: those who take after the monkey father, and those who take after the ogress mother. The first type are tolerant, trustworthy, compassionate, hard-working and softly spoken. The second type are lustful, wrathful, profit-hungry and competitive, physically powerful with a loud laugh. Never content to be at rest, they are always changing their minds, leaping into action and allowing their hot tempers to get them into trouble.

It was certainly true that Tibet’s early enemies regarded its people with fear and trepidation. But, like the legendary monkey children, the early Tibetans had another side to them. They were eager to learn from the more established cultures that they encountered in the course of their military expansion. Though not without a culture of their own, the Tibetans were hungry for more. And so they learned from Nepal, India, China and Persia, adopting and combining elements from each to create a distinct culture of their own. Lhasa, the empire’s capital, became the centre of these new developments.