Here is a sample of later Viking ships that are likely to be representative of the various types and sizes of ships used by the Saxons. The ships could carry more than the crew mentioned as passengers. It should be noted, however, that even bigger ships were used in Scandinavia already before Christ on the basis of extant carvings so this should be seen as a conservative estimate for the maximum size of the ships.

Haywood (25) considers the origins of the Saxons even more obscure than that of the Franks. What is known is that they were a confederacy of closely related coastal tribes of the North Sea littoral. The earliest reference to the Saxons is in Ptolemy’s Geography, which dates from c.150. The book places the Saxons next to the Chauci on the North Sea coast. The Saxons were presumably a confederation that originally included at least the Reudingi and the Aviones in the second century. In the third century, when these tribes spread westward to the Ems, parts of the Chauci and Frisians probably joined the confederation. In my opinion, the Saxons were probably originally tribal warriors who carried seaxes/scramasaxes (short single-edged swords) that had gathered around some specific chieftain who then managed to achieve a dominant position first in his own tribe and then among the neighbouring tribes.

The first recorded Saxon naval raid occurred in the 280s, later than the first known Frankish piratical raids. However, this is probably a mere reflection of the poverty of sources for the third century, because the rise in sea level resulting from the marine transgression was sure to ruin their agriculture and serve as inducement to raid their more prosperous neighbours. In support of this Haywood (32) has noted that the archaeological record demonstrates that the coastal areas of Britain and northern Gaul were definitely suffering from piracy already during the 270s. He has also speculated that the Franks began their naval raids already during the 250s and that the Saxons were almost certainly active already during the 270s. In fact, the best evidence for the seriousness of the naval threat comes from the great extension of the coastal fortification system in c.250–280 on both sides of the English Channel. Haywood (36) considers it probable that most of the forts in this sector were built only after the collapse of the Gallic Empire in 273, but that some of the defences were already built before that.

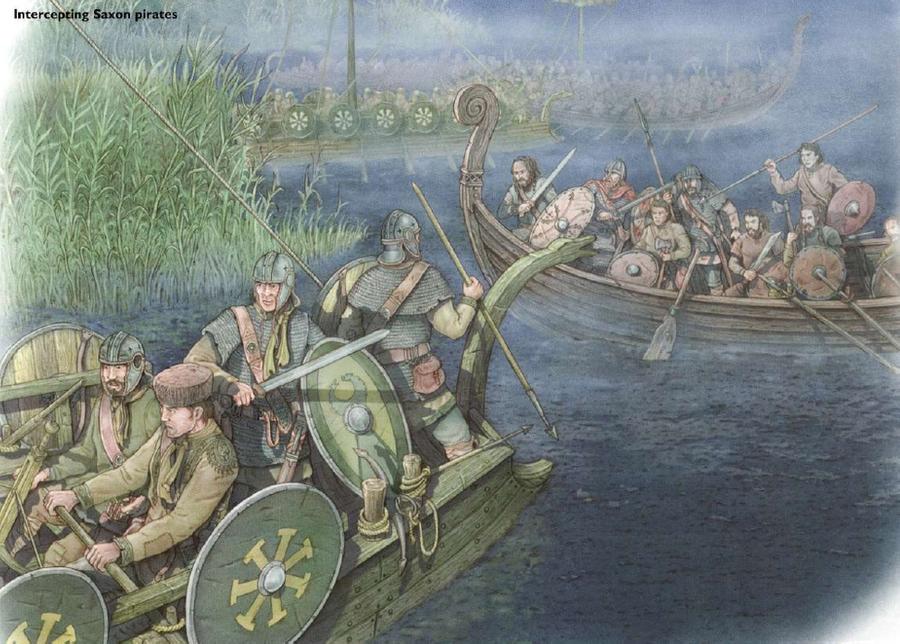

The new chain of fortifications came to be known as the ‘Saxon Shore Forts’. Structurally these fortifications were a departure from earlier Roman practice. The builders clearly stressed the defensive aspects over offensive ones. The fortifications had semi-circular external bastion towers, thick walls, massive gatehouses and well positioned wall-mounted ballistae. However, the defensibility of the site was not the decisive factor, but rather the suitability of the site to serve as a base of naval operations. The fortifications were concentrated in the Straits of Dover, because it formed a natural bottle-neck through which the pirates had to go if they wanted to raid the coasts of southern Britain, Gaul or Spain. The Straits gave the Romans their only real chance of regularly patrolling the seas. The system of forts and naval bases made it relatively difficult for a large fleet to pass through undetected, but it did not provide any real security against individual or small groups of raiding ships that could easily evade detection at night or in a fog or rain. However, once the raiders landed, their presence was no longer a secret and they could be intercepted on their way home by sea, or on land. Despite the fortification programme, the situation worsened. In 280, unknown barbarian raiders destroyed the Roman Fleet of the Rhine while it was laid up for the winter. Consequently, during the 280’s the Franks, Saxons and even the Heruls of Denmark raided the coasts of the Roman Empire. The Roman response was not long in coming. In 285 the Menapian Carausius was appointed as overall commander of the Roman naval forces of the Channel.

The extensive building program of coastal defences and the appointment of Carausius proves that Roman military authorities considered the Franks, Saxons and their allies capable of mounting large scale amphibious military operations that posed a very serious threat to the Romans in Britain and Gaul. The motives behind the raiding were undoubtedly the typical ones: the glory-seeking of young warriors and chieftains; the lure of booty; and the periodical bad harvests. The need for the youths to prove themselves in combat may have been quite an important motivator behind the raids.

Despite the quite sizable Roman countermeasures, the numbers of the Saxon raiders are likely to have been small. Even after the conquest of England, the Anglo-Saxon genes in Britain amount to only about five per cent of the total population. In the Saga of the Jómsvikings (9), the naval forces of the Danish king Harold consisted of a mere 50 ships (a minimum of c.1650 men) and of the rebel Svein of 30 ships (a minimum of c.990 men). The maximum numbers of ships and men for the Saxons, when all of the chieftains cooperated, can also be gauged from the saga. The naval force of the Danish Jómsvikings consisted of 120 large ships (possibly c.100/ship equals not more than 12,000 men) and that of the Norwegian Earl Hákon of more than 360 ships (possibly c.100/ship equals not more than 36,000 men). This means that in the ideal circumstances, when all of the Saxon chieftains and their allies cooperated, one can hazard a guess that the Saxons could achieve a temporary local military superiority against the Romans, as seems to have happened during the years 367–370. However, it would have been far more typical for the naval force to have consisted of a few raiders ranging from 3 to 10 ships. A fleet consisting of 30–50 ships (perhaps about 50 men per ship making altogether about 1,500–2,500 men) would already have been a major incursion. In other words, when the Roman forces occupying Britain already had their hands full in dealing with the tribes of northern Britain and the Irish (Scotti) raiders, even relatively small naval forces could seriously threaten the security of the more peaceful and prosperous and less well defended parts of the island.

The Saxon (and Herul ships) probably resembled closely those of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. The clinker-built ships were powered by both sails and oars. (See above.) The typical crew on board a raiding ship was about 30 or 50–60 men. For example, according to Haywood, the Herul ships that raided Lugo in 455–7 had crews of about 55 men. The largest ships of some major figures like kings or chieftains had probably about 100 to 120 men crews on board. If one can judge from the results of Roman countermeasures, these fleets and ships were not able to oppose the Roman fleets if the Romans concentrated their naval forces to defeat the raiders.

Roman galleys had many advantages over the Germanic vessels. The largest Roman war galleys had bigger crews, were taller and had towers, ballistae and catapults. Most importantly, the Roman war galleys also had rams or spur-rams.

As regards to armament on board, the Saxon raiders appear to have used a combination of bows, thrown stones, spears, shields and seaxes/scramasaxes. As regards to the last mentioned weapon, the seax/scramasax, from which the Saxons got their name, was undoubtedly used by Saxon heroic champions/berserks when they boarded enemy vessels and fought in close quarters combat. The shortness of the sword/long-knife helped during close quarters fighting and stood as a proof of its user’s manhood. As regards to the use of missiles, the Saxons were clear underdogs. The Romans used far more effective artillery and (composite) bows than the Saxons and in much greater quantities. In fact, it is quite probable that the principal missile weapons of the Saxons on board their ships were stones thrown by hand or by sling. The later Viking Saga of the Jómsvikings (15, 21) contains a good description of the use of thrown stones in a naval battle. It also describes how the clinker-type of ships were often tied together to form a continuous fighting platform behind which could be deployed the reserves and how in naval combat the attackers aimed at outflanking the enemy so that they could bring groups of ships against smaller numbers of ships, and how in boarding the berserks spearheaded the attack.

From later sources we learn that on land the Saxons employed typical Germanic battle tactics based on the use of shieldwalls and infantry wedges. The Saxons could ride to the site of battle, but they usually fought on foot using only spears, seaxes and shields. Only the elite wore armour and helmets and used true two-edged swords. The combat naturally began with challenges to single combat, followed by a short exchange of missiles that was followed by attack. Just before contact was made, those who had javelins threw them and then the men fought with spears and shields. The swords, axes and seaxes were only used when the spear had become useless. As is obvious, the Saxons were not numerous enough to pose any real threat to the Roman Empire, even if they could cause considerable economic damage. The location of the Saxon territories also posed a problem for it was possible for the Romans to conduct punishing raids only by naval raids, which they undoubtedly did even though the sources fail to mention this.