Bulgaria under Ivan Asen II

Byzantine Emperor Basil II, who succeeded his uncle John Tzimiskes in 976, immediately sent a new army to deal with the brothers, but his main concern was a rebellion by a Greek commander in Asia Minor. Samuil and his brother Aron (his other brothers had died) were able to hold off the Greeks. Roman, who had escaped from Constantinople and was now tsar but childless, gave up the throne to Samuil in 978.

Samuil was the last emperor of the First Bulgarian Empire, and he spent his reign in wars against the Byzantine emperor Basil II. Samuil liberated northern Bulgaria and for 10 years raided Byzantine Thrace and Greece. In 986, Basil was ready to face the Bulgarians and marched through Philippoupolis to Sredetz, Samuil’s home base. However, he made too many mistakes to take the city. He divided his troops, leaving a contingent behind to guard his rear. The Bulgarians burned their crops and even managed to steal the cattle the Greeks brought with them, cut- ting off the Byzantine food supply. The commanders placed their siege equipment in the wrong place and Bulgarians were able to destroy it. The siege lasted less then three weeks before Basil retreated. Further- more, the commander he left in the rear went back to Philippoupolis, and Basil believed he was going to challenge him for the throne. Samuil, who had been fighting in Thrace, caught the emperor at the Gates of Trajan, a fortification outside of Sredetz. Here rumors and fear overtook the Byzantine troops, throwing them into despair. The Bulgarians seized their opportunity, rushing the Greek camp and winning a great victory, but Basil managed to escape, although the valuables he had brought with him fell to the Bulgarians.

Samuil followed up his victory with more raids into the empire, not only Thrace and Macedonia but also down into the Greek peninsula as far as the Peloponnesian cities and to the Adriatic, capturing Dyrachachium (modern Durres). He also defeated the Serbs and Hungarians. In 990, he moved his capital to Ohrid in western Macedonia. The city became the seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate as well. In fact, Samuil, unable during the wars to regain recognition of the imperial crown, asked and perhaps received acknowledgement of his titles from Pope Gregory V. (The church was still nominally united and did not reach an irreparable breach between Eastern and Western Christianity until 1054.)

In 988, Samuil attacked the Serbs to prevent them from joining Basil. The Serbian prince, Jovan Vladimir, retreated into the mountains. Samuil then divided his force-one part to continue the fight against Prince Jovan and the bulk to attack the port of Ulcinj. Jovan refused Samuil’s entreaty for his surrender, but a number of Serbian noblemen went over to the Bulgarians in light of the hopelessness of their cause, and Samuil took Jovan prisoner. The tsar then marched up the Adriatic coast through Dalmatia, capturing Kotor and laying waste to the towns and villages around Dubrovnik, although he failed to take the city. He then proceeded into Bosnia and Croatia, where rival dukes were in constant warfare. Siding with some against the others, he was able to win the dukes over as his vassals.

Meanwhile, he allowed his daughter Theodora to marry Prince Jovan, her father’s prisoner, who had won her love. Samuil restored Jovan’s lands and made him his vassal. He also made a treaty with Hungary by having his son Gavril Radomir marry the daughter of the Magyar grand prince Geza. Thus becoming the master of Bulgaria, Macedonia, Thrace, Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia, he brought his empire to a renewed height by the end of the century, reversing the disasters of the last years of Peter and the reigns of Boris II and Roman and rivaling the achievements of Simeon.

Basil, determined to follow up on his uncle’s triumphs and reconquer Bulgaria, diverted his forces from his war with the Moslems to attack Samuil. In 1001, he sent a large force to capture the Bulgarian fortresses north of the Balkan Mountains, capturing the old capitals of Pliska and Preslav. The following year, the Byzantines marched to the west, retaking Thessaly. Samuil’s’ commander Dobromir, related to the tsar by marriage, surrendered and joined his troops to Basil’s. Samuil was now on the defensive, and eventually the Greek emperor was able to retake Thessaly and resettle the Bulgarian population farther north.

Samuil’s relations with the Hungarians also deteriorated. After Geza died, the Bulgarian tsar supported the rivals of his son, the glorious St. Stephen, regarded as the founder of modern Hungary. The marriage of Samuil’s son Gavril to Geza’s daughter was dissolved. Stephen, along with the Byzantines, attacked Bulgarian territory on the Danube, and Hungary replaced Bulgaria north of the river. The war of attrition continued for another decade. Each year Basil would raid into the Bulgarian lands, pillaging the villages. The usual Greek path was north through the Struma River valley, so in 1014, Samuil decided to take a decisive stand at the village significantly named Kliuch, “the key,” the gateway to the valley.

Samuil fortified the approaches to the village with wooden walls and stationed an army of more than 15,000 men behind it. While certainly not comparable to the massive walls of Constantinople nor even the fortifications of the Bulgarian capitals, they were strong enough to cause Basil difficulties, and the Greeks suffered many losses in their attempts to breach them.

Despite the Greeks’ difficulties, at the end of July, Nikephoros Xiphias, the Byzantine governor of Plovdiv, managed to lead his troops around the walls and attack the Bulgarians from behind. The Bulgarians left their defenses to face the new threat, finally giving Basil an opportunity to break through. The Byzantine army killed thou- sands of the Bulgarians and took thousands more prisoner, but Samuil managed to escape with the aid of his son Gabriel, who gave up his own horse to his father.

Basil then abandoned his march north, but on the retreat he managed to capture Melnik, another important fortress protecting the route. According to the contemporary accounts, Basil blinded all thousands of the Bulgarian captives, leaving one in a hundred with one eye to lead the others back home. He accomplished this cruelty either as a punishment for the revolt against him, as he regarded himself as their sovereign, or in retaliation for the killing of a Greek commander. The legend further has it that on seeing the pitiful sight when the soldiers returned, Samuel died of a heart attack in October 1014. The war, however, continued with Samuil’s son Gabriel Radomir leading the empire. In 1015, Ivan Vladislav, Samuil’s nephew, conspired with Byzantine agents to murder Gabriel and took the throne himself. He also murdered his brother-in-law Jovan Vladimir, the duke of Zeta (present-day Monte- negro). He did not conclude a peace with Basil but continued the war. However, the losses were too much to bear. Many Bulgarian governors and commanders went over to the Byzantines. In 1018, Basil dealt the ” decisive blow at Dyrrhachium (modern Durres). Ivan mortally fell in the battle and his army retreated. The remaining governors and commanders surrendered, and Basil incorporated Bulgaria up to the Danube into his empire, restoring the lands that had been lost since the seventh century. He was awarded the appellation Bulgaroktonos, Basil the Bulgarslayer.

Basil lived only a few more years after 1018, and then after a short reign by his brother, the empire fell into a half century of chaos, intrigue, and civil war marvelously described by the Byzantine historian Michael Psellus. Basil’s nieces Zoe and Theodora, the former’s various consorts, and other interlopers ruled off and on until Alexios I Komnenuos ascended the throne in 1081 and established the more stable Komnenid dynasty. After Basil’s victory, the emperor initially incorporated Bulgaria into several provinces called themes. The Byzantine aristocracy absorbed the boyars. The Bulgarian church retained its autonomous status, remaining in Ohrid, but as a bishopric rather than a patriarchate. Thus Macedonia remained part of Bulgaria. Constantinople left the Bulgarian tax and land-owning laws intact as well. Bulgarians filled the ranks of the military in the themes. Gradually, however, the emperors passed rule of the land over to Greeks. They shifted Bulgarian boyars to other lands in the empire or bought them out. Greek clerics filled the posts in the churches. Many of the Greeks that came into the Byzantine themes treated their positions as temporary sinecures and had as their first priority exploiting the available wealth. Romanos II (reigned 1028-1034) replaced the Bulgarian tax code with the harsher Byzantine system.

DELYAN’S REVOLT

In 1040, Peter Delyan, claiming to be the son of Gabriel Radomir and hence the grandson of Tsar Samuil, raised the standard of revolt in Belgrade. However, scholars cannot confirm his ancestry. Perhaps he may have been the son of Marguerite, Gabriel’s Hungarian wife, which would have made him the nephew of St. Stephen as well. However, some believing that a son of Radomir could not have escaped the murders carried out by Ivan Vladislav think him to be an imposter making the claims to add weight to his rebellion. Delyan had been one of the Bulgarians taken captive after Basil’s victory and was a servant to a Byzantine aristocrat. When he escaped, he fled to Belgrade on the Bulgarian-Hungarian border.

Here Delyan won support of the local Bulgarians dissatisfied with Byzantine rule and adopted the name of the sainted tsar Peter I. At the head of a growing army of Bulgarian rebels, Peter moved southward toward Ohrid, killing Byzantine officials along the way. At the same time the boyar Tikhomir, an experienced warrior from Dyrrhachium who heard of the revolt, had himself declared tsar and led a second army eastward to Ohrid. The two armies met and Peter and Tikhomir both appealed to the assemblage to choose which one should rule. Peter’s eloquence won the day and the Bulgarians chose him; he then executed Tikhomir. The enlarged army gathered more rebellious Bulgarians and captured territory from Albania, Macedonia, and deep into Greece as far as Corinth.

Another pretender to the crown Alusian, a grandson of Samuil’s brother Aron, arose in Armenia, where the Byzantines had transported many Bulgarians after the fall of the First Empire. He had been a governor of an Armenian theme but lost favor during the many twists and turns of the notorious Byzantine intrigues. Learning of the rebel- lion in the Balkans, he clandestinely made his way to Delyan’s camp, where the pretender welcomed him as a cousin and put him in charge of a large force of 40,000 men assigned to attack Thessaloniki. The ven- ture failed, and Alusian lost more than a third of his army.

Relations between the cousins deteriorated, and Peter suspected Alusian of treason. Alusian feared Peter conspired against him. He invited Delyan to a feast and, waiting until the tsar was drunk, had his followers fall on him and take out his eyes. Alusian now took over the revolt, but losing in battle again, he went over to the Byzantines. Emperor Michael V now gathered a large army of Greeks and mercenaries and put down the revolt, decisively defeating the Bulgarians led by the blind Peter Delyan at the Battle of Ostrovo in 1041. The fate of Delyan remains unknown. In the following weeks, the Greeks suppressed the remainder of the rebels.

THE ASENIDS

Toward the end of the century, a number of new revolts broke out, but the Byzantine emperors were able to quash them. The most important was in Skopje led by Georgi Votekh and Prince Michael of Zeta. After initial success in Skopje and elsewhere, however, the Byzantine forces suppressed the uprising. Constantinople suffered more serious problems with the conquest of its southern Italian lands by the Normans and its Middle Eastern territories by the Moslems. Alexios I gave up on hopes for Italy, but he asked for help from the West in retaking Syria and Palestine. The result was the Crusades. The Western crusaders who came east beginning in 1096 came not to return the lands to the Byzantine emperors but rather grab the Moslem (and some Middle Eastern Christian) lands for themselves. The crusading masses in the eleventh and twelfth centuries marched through Bulgaria despoiling the land, believing that because they were on a holy cause, they had the right to take what they needed without payment. By the end of the century, Byzantine rule in Bulgaria was almost nominal and the local Bulgarian aristocracy, in essence warlords, took over.

In the 1180s, a new series of tax riots broke out over levies imposed to finance the marriage of Isaac II of the new Byzantine Angelid dynasty to a Hungarian princess. Two noblemen, the brothers Ivan Asen and Todor, requested that Isaac appoint them autonomous governors of all the Bulgarian lands. The brothers’ origins and ethnicity are obscure. Bulgarians maintain that they were descendents of the tsars of the First Empire and therefore had the right to rule as tsars themselves. However, others have raised doubts, especially the Romanians, who claim they were Vlachs and hence related to them.

When Isaac turned down the brothers’ request, they returned home and took the lead of the rebels, declaring the older, Todor, tsar Peter II. However, Ivan Asen led the military campaigns and left his name to the new dynasty, the Asenids. With the Angelids engaged in a dynastic struggle, the Bulgarians had great success raiding into Thrace and reestablishing the Bulgarian Empire. The brothers established their capital in the picturesque town of Great Turnovo on the meandering Iantra River. A replica of the castle was built in the late twentieth century and the Bulgarian tourist agency exhibits a laser light show to demonstrate to native and foreign tourists its pride in its Medieval past.

Asen, too, was given the title of tsar in 1188, the two brothers ruling together. The war against the Greeks continued for a decade, during which despite several reverses the tsars were able to consolidate their rule. In 1196, however, Asen was assassinated by a relative angered over a private matter, and assassins also murdered Peter the following year. The throne next fell to a younger brother, Kaloian, who continued the war against the Byzantines, capturing Macedonia and Greek cities along the Black Sea coast and defeating the Hungarian allies of Constantinople, adding land north of the Danube to his empire.

KALOIAN

Kaloian began negotiations with both Pope Innocent III and Emperor Alexios III for recognition of his title. The churches had by now split and the rivals were anxious to have the new powerful ruler on their respective sides. Thus Kaloian received recognition from both. Furthermore, the Byzantine Empire met with disaster. The Angelid family squabble brought in the crusaders of the infamous Fourth Crusade, who, instead of going on to Palestine after restoring their Angelid sponsors, installed one of their own, Baldwin of Flanders, as Emperor Baldwin I of the Latin Empire, which lasted in Constantinople until 1265. The Byzantine themes now became more than a dozen feudal fiefs in the Western style awarded to other crusader nobles, now vassals of Baldwin. In addition, other powerful states grew on the borders of the Byzantine Empire. The Greek emperors established their new empire in Nicea across the Bosporus until their return to Constantinople in 1265. The Ottoman Turks would appear later in the century. The Norman kingdom of Sicily also staked it claims. The Republics of Venice and Dubrovnik (Ragusa) appeared as wealthy mercantile states. The Serbian kingdom reached its zenith, and there were even more that would complicate the affairs of the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean, making it one of the most vexing shatter belts of world geopolitics for the rest of history.

Kaloian sent envoys to draw up the border between Bulgaria and the new empire, but Baldwin contemptuously dismissed them and vowed that he would retake the renegade state. Kaloian’s appeal to Pope Innocent III was of no use because he had already condemned the crusaders for their attacks on Christian states. The Bulgarian tsar then fomented a revolt among the Greek nobles of Thrace, and when Baldwin marched to Adrianople, he found the city loyal to Kaloian, who soon arrived with his army. The Latin troops then attacked the Bulgarian forces but suffered a humiliating defeat. Kaloian captured Baldwin and carried him off to Turnovo, where he died (perhaps being executed). Legend has it, however, that the tsar imprisoned him in his castle, a remnant of which, as mentioned above, survived through the centuries, and the locals called one part of the edifice “Baldwin’s tower.”

Kaloian followed his victory with further attacks on the Latin Empire, conquering all of Thrace. Boniface of Montferrat, the king of Thessalonki, the last surviving leader of the Fourth Crusade, died in the battle. However, Kaloian himself died as well, perhaps murdered by one of his own allies. His nephew Boril (reigned 1208-1217) succeeded him.

However, while Kaloian’s reign ranks as one of the greatest and most celebrated in Bulgarian medieval history, his nephew’s was a significant disappointment. His ineptitude in political and military affairs led to the loss of Thrace and an invitation to invasion from both the Latins and Hungarians, only resolved by papal mediation and diplomatic marriages. In Bulgaria itself, a number of governors unhappy with the tsar and suspecting him of being involved in the demise of Kaloian plotted against him in 1217. Ivan Asen’s son overthrew Boril and assumed the crown as Ivan Asen II.

Tsar Asen was able to restore Bulgarian territory by diplomatic treaties, including his marriage to a Hungarian princess. When a Greek pretender to the Byzantine throne attacked him from Epirus on the Adriatic coast, Asen defeated this foe and restored Bulgarian power in the western Balkans. The Second Empire became a force to be reckoned with in European affairs and a commercial epicenter for southeast Europe. The decline of the church in Constantinople and Kiev made the Bulgarian patriarchate an ecclesiastical power as well. However, his successors could not hold the state’s dominant position. Bulgaria not only suffered from internal revolts and coups but also faced foreign enemies again, especially the restored Byzantine Empire and the Mongols, whose raids were devastating all of Eastern Europe.

The Bulgarians kept their lands intact, although they paid tribute to the Mongols and fought them in a number of battles. In 1277, one Ivailo defeated the Mongols and briefly became tsar. His importance is not his reign but his legend. Although his origin is obscure, and he may even have been a boyar, the Bulgarian myth is that he was a peasant. The story of the peasant king resonated to modern times when the country had no native aristocracy, and everyone was of peasant origin. Thus they placed the mantle of hero around Ivailo’s shoulders.

IVAN ALEXANDER

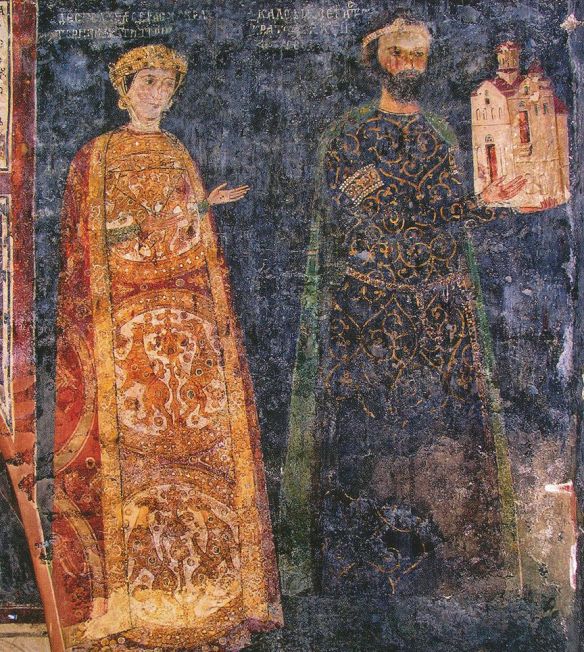

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Mongol control over Bulgaria loosened, and the new tsar Todor Svetoslav (reigned 1300-1322) defeated the weakening Byzantine Empire, restoring Bulgaria to its former strength. In 1331, Ivan Alexander, the governor of Lovech, descended from the Asens on his mother’s side, assumed the throne after a dynastic struggle. Under him the empire reached a new peak, its last in the Middle Ages. Having trade connections with the Italian and Adriatic mercantile republics, Turnovo became a cosmopolitan commercial and cultural center. Indeed, the tsar sent his first wife to a convent and chose a new bride, Sara, from the large Jewish mercantile community in the capital. Unhappily, however, Sara-or Theodora, as she was called after her conversion to the Christian faith-was not kind to her former coreligionists and joined the priests and bishops in their campaign against Jewish influence. Turnovo at this time was also a major religious and cultural center with many churches and monasteries. The most famous religious artifact of Medieval Bulgaria is Tsar Ivan Alexander’s Tetraevangelia, the four gospels, illustrated and translated into Medieval Bulgarian. One of the illustrations is that of the tsar and his second wife Sara-Theodora and their two sons. The tsar had several sons, whom he established as corulers, and several daughters, one of whom married the Byzantine emperor Andronikos IV Paleaologus and another who was sent off as a hostage concubine to Sultan Murad IV of the Ottoman Turks.

The latter now became the major factor in the power struggle of the Balkans. While the remnants of the Latin Empire, the various Slavic lords, the Italian princes, the Hungarians, and others fought each other for territory and influence, the Turks gradually increased their hold on Asia Minor and then Europe. The struggle would reach its culmination in 1453, when after his predecessors had conquered virtually all of the Balkans, Sultan Mehmed II finally took the decrepit Byzantine capital. The struggle among the Christians took the form of a religious battle over loyalty to Pope or Greek emperor symbolized by which version of the Apostles’ Creed their subjects should follow. (The difference centered merely on a three-letter suffix of a single word.) However, the real issues were wealth, land, and power, and the kings, dukes, and lords would change church and alliance as the politics dictated. The fratricidal struggle gave the Turks ample opportunity to move in and take over.

Ivan Alexander, as did all other rulers, took part in these wars and intrigues. Sending Kera Tamara, his daughter, off to Murad’s harem was just another alliance. Obviously, political realpolitik took precedence over religious conviction. To deal with the complex situation resulting from the fragmentation of power in the Balkans in 1356, Ivan Alexander set up his son Ivan Strashimir as independent tsar of Vidin in northwest Bulgaria.

In 1363, the Turks established their base in Europe in Adrianople (Edirne) and the next year invaded Bulgaria and captured Thrace, including the important center of Philippoupolis (Plovdiv). A coalition of Bulgarians and Serbs prepared to meet the Turks in battle in 1371. Ivan Alexander died before the conflict began, and the Turks won a great victory at Chernomen near Adrianople. Ivan Shishman succeeded his father as tsar of Bulgaria in Turnovo. The Ottomans followed up their victory with new incursions into the Christian states, forcing Ivan Shishman into vassalage. The princes and rulers of Hungary and the Italian states and cities also moved in for the kill, taking over parts of the area. The Turks won a crucial and a legendary victory against the powerful Serbs in 1389 at Kosovo Field. They followed this up by capturing Turnovo in 1393 and Vidin in 1396. Although a few Bulgarian commanders were able to hold out for a few more years, the Second Empire came to an end.