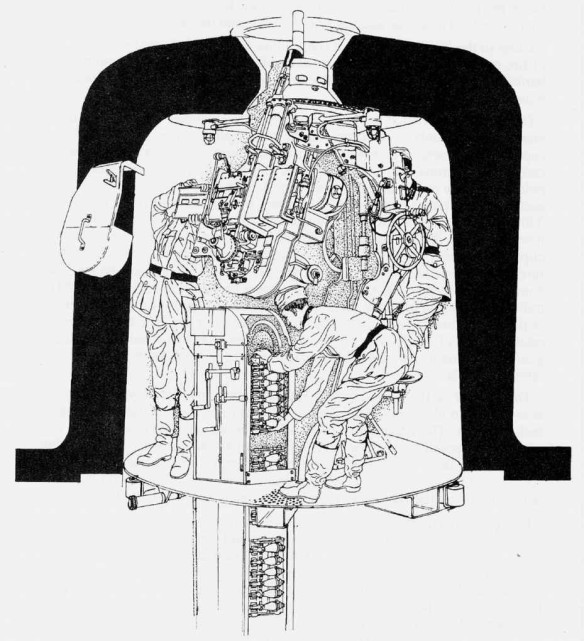

Diagram of German M19 5cm automatic mortar as sited in the Channel Islands and at points on the Atlantic Wall.

Rheinmettall-Borsig produced ten studies into developing a complete system for an automatic mortar before making a final choice which would become the M19 5cm Maschinengranatwerfer. The operational role of the system was to provide firepower to cover areas of ‘dead ground’ which could not otherwise be observed. This was usually an area on the coastline with steep cliffs, but that was not exclusive. Apart from firing the 5cm calibre mortar bomb, the weapon used in the M19 system was completely different to the standard GrW36 used by the infantry. Using standard dismountable mortars in such a defensive role would have only been a short-term solution and they would have needed to be removed periodically for service. Emplacing a weapon mounted in a specially-produced turret or cupola would provide a permanent position, ready to provide all-round 360-degree traverse and able to come into action at a moment’s notice to cover all points of approach to the defensive site. Initially, these automatic mortars were intended for installation in the Westwall and the Eastwall, a defensive system also known as the Oder-Warthe-Bogen Line. This was built between 1938 and 1940 on the border between Germany and Poland. It covered a length of around 20 miles and included around 100 main defensive emplacements. After the successful campaigns in 1939 and 1940, it was decided not to install the weapons in these locations and instead they would be sited at intervals along the Atlantic Wall, which included several being built on the Channel Islands of Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney.

The M19 installation on the island of Jersey was built at Corbière Point at the western end of the island, which was turned into a strongpoint to defend the headland. From here its high rate of fire could be useful in engaging targets at close quarters and overlap with the firepower of machine guns and two 10.5cm field guns also sited at the point. The neighbouring island of Guernsey had four M19 automatic mortar installations, including one located at Hommet, overlooking Vazon Bay on the north-west coast, where its firepower could be integrated with that of machine guns, at least three pieces of artillery with 10.5cm calibre and a 4.7cm gun of Czechoslovakian origin. On Alderney there were two M19 strongpoints with other similar installations built along the much-vaunted Atlantic Wall, including three in Norway, nine in Holland, one in Belgium, twenty-two along the French coast and twenty along the Danish coastline, with four more planned but not built. For such a small weapon it absorbed a huge amount of resources in manpower to build the emplacement, with tons of concrete and steel in its construction. The sites of the M19 automatic mortars were out of all proportion compared to those built for heavier weaponry in defensive positions. The M19 mortar could fire HE bombs at a rate of between sixty and 120 rounds per minute, although the higher rate of fire was rarely used in order to minimise stresses and prevent the weapon from overheating. The crew could engage targets at ranges between 54 and 820 yards, which was closer than artillery could achieve, and together with support fire from other weapons such as machine gun, any infantry attack would have been met with fierce opposition. Indeed, one M19 position on the Eastwall held out for forty-eight hours when attacked by troops of the Red Army in early 1945.

The M19 weapons were mounted in steel cupolas which had an internal diameter of 6ft 6in to accommodate the three-man crew during firing. Initially, there were two main designs of cupola, the 34P8 and the 49P8, but it was a third type, the 424PO1, which became the most widely used with armour protection 250mm thick. The cupolas were mounted on specially-prepared bunkers designated ‘135’, with concrete protection up to 11.5ft thick, and the ‘633’, which was the most common design and the type used in the Channel Islands. The M19 bunkers were divided into several rooms including the firing room and had accommodation for up to sixteen men. Each bunker had its own independent generator to provide power to traverse the firing platform and cupola, but in the event of a power failure the weapon and cupola could be elevated and traversed by means of hand-operated wheels. The ammunition storage room had racks for thirty-four trays, each pre-loaded with six bombs, giving a total of 204 bombs ready to fire. Ammunition boxes containing ten bombs each to reload the spent trays were stored in this room, and it was the task of the crew members to reload these. In total an M19 bunker could have ammunition reserves of up to 3,944 bombs stored in readiness for use. These bunkers were equipped with field telephones and optical sight units such as the Panzer-Rundblick-Zielfernrohr, an armoured periscope with a magnification of × 5. Because it was an indirect fire weapon, the M19 had to be directed on to its targets and integrate its fire by overlapping with neighbouring weaponry.

The firing platform on which the mortar was mounted could be elevated when firing and lowered when not in use. The loaded ammunition trays were fed up to the platform by means of an elevator where the loader removed them and fed the trays into the left-hand side of the weapon’s breech. As it fired, a mechanism moved the tray along to feed the next bomb into the weapon, and the process continued until the empty tray emerged on the right-hand side of the weapon, where a handler removed them and placed them in the descending elevator section. These were removed by another member of the crew and taken to the ammunition room, where they were reloaded ready for reuse. The M19 could fire the standard types of Wurfgranate 36 bombs, which these were fitted with colour-coded graduated propellant charges to be used according to the range required. The red charge was for use at ranges from 22 to 220 yards and the green charge was for ranges from 220 to 680 yards. There were training bombs which had no filling and could not be fired, which were really for familiarising crews with handling procedures of the weapon. There were two training systems developed to teach crews how to operate the M19; the first was the Sonderanhangar 101 mounted on a trailer and the other was the Ubungsturm, which replicated the complete cupola layout.

Preparing the weapon to fire, the operator lifted the barrel clear of the breech by means of a cam and lever mechanism which allowed a bomb on the loading tray to be aligned with the chamber. As the barrel was lowered over the bomb, the firing pin in the breech was activated to initiate the propellant charge. The recoil forces on firing unlocked the barrel a fraction of a second later and the cam mechanism lifted the barrel clear of the breech, and another bomb was loaded ready to fire as the tray was fed through.

As the Allied campaign to liberate Europe continued in the second half of 1944, the Germans had to rethink their defensive strategy. From September 1944 they renewed construction work on the Westwall to improve defences and began to install M19 systems at certain locations. The actual numbers of M19 systems built and turrets installed varies according to sources. Some, for example, state that perhaps seventy-three such installations were built in the Atlantic Wall. These did not cause the Allies any unnecessary problems and those along the Westwall were largely ineffective, while those in the Channel Islands never fired a shot in anger. In summary, it was indeed a great deal of effort for such a small weapon which did not play a decisive role in stopping or even slowing down the Allied advance.