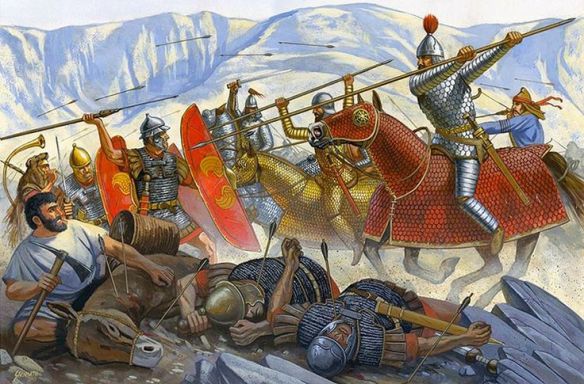

Parthian Cavalry charge.

Campaign against the Parthians Mark Antony, 36 BC. Oppius Statianus (legate Mark Antony) guarding the Roman baggage and siege equipment,

To his core, Antonius was a soldier – and a proud one. It was said he believed that there would be no better death for him than that by battle. As governor general in the East he sought to settle an old score. He conceived a military campaign against Rome’s nemesis Parthia. It was motivated by a desire to restore national honour after Crassus’ humiliating defeat at Carrhae in 53 BCE by Orodes II, and the Parthian incursions led by the quisling Q. Labienus on behalf of King Pacorus I in 40 BCE. After two years Antonius had assembled an army of his own troops supplemented by men and materiel from client kings and allies. At the start of his campaign he had 60,000 Roman infantry, together with 10,000 Celtiberian cavalry, and 30,000 assorted soldiers counting alike horsemen and light-armed troops from allies. Yet he complained that he was still short of the troops he had been promised by Caesar in return for the ships he had provided for the Sicilan War against Sex. Pompeius. Antonius would have to bolster his numbers by calling on Rome’s sole ally in the region. North of the Parthian province of Mesopotamia lay the great state of Armenia ruled by Artavasdes II, son of Tigranes the Great. Artavasdes II had been an ally of the Romans, but when they were defeated at Carrhae, he was forced to switch sides. Seeing an opportunity to free himself of Parthian obligations, he now switched sides again, this time allying himself with Antonius. On the advice of Artavasdes II of Armenia, Antonius planned to invade Parthia from the north – not from the west – by invading the Parthian client kingdom to the east of Armenia called Media Atropatene. Bordering on the Caspian Sea, it was ruled by Artavasdes I – no relation to the Armenian – and the loyal ally of the Parthian king, Phraates IV. Antonius’ decision was fateful. His advance with thirteen legions reached Phraaspa, the strongly fortified capital of Media Atropatene. According to Plutarch, the siege engines, which required 300 wagons to transport them, as well as a giant battering ram he would need to capture walled cities, he decided to leave behind – according to Velleius Paterculus, he lost two legions and their siege equipment to the Parthians. There his campaign halted. Unable to take Phraaspa, Antonius now found himself exposed on the plain outside the city. The Parthians soon came to the aid of Artavsades holed up in his city. They attacked Antonius’ supply train and, when rations were cut, his own soldiers mutinied. His fair-weather ally, Artavasdes I of Armenia, deserted him. Undaunted, in October that year Antonius demanded that the Parthians return the eagle standards and the Roman prisoners they had taken. The Parthians refused and replied that they would only permit him to leave the region unmolested. Without leverage, Antonius could do no more than accept the terms and ordered his army to head back to Syria. Before departing, he received a tip-off that he should expect an ambush and to avoid it he decided to take a route over the mountains. He was pursued by the Parthians and through twenty-five brutally harsh days Antonius struggled to lead his men to safety – Livy says he covered 450km (300 miles) in just twenty-one days. After withering attacks he finally reached Antiocheia on the Orontes in Syria. The failed campaign had come at terrible cost: 20,000 of the infantry and 4,000 of the cavalry had perished, not all at the hands of the enemy, but more than half by disease. They had, indeed, marched twenty-seven days from Phraaspa, and had defeated the Parthians in eighteen battles, but their victories were not complete or lasting because the missions they had pursued were ineffectual and short-term in outlook.

The following year Octavia brought from Italy several cohorts of cavalry to Greece to assist her husband, but at Athens she was told to proceed no further and remain there. Octavia understood completely what was afoot, and despite the personal hurt it caused her, nevertheless wrote to Antonius asking which of the many things she had with her should she bring to him. Anticipating her husband’s needs she was bringing clothing for his soldiers, pack animals, money and gifts for the officers and his friends, and in addition, 2,000 hand-picked, fully equipped men of the Praetorian Cohorts. Antonius’ political and romantic interests, however, now lay in Alexandria. A key financial backer of his wars was Queen Kleopatra of Egypt. He had met her for the first time in 47 BCE when Iulius Caesar backed her claim and, after the Alexandrine War, put the then 22-year-old woman on the throne. Caesar was famously seduced by her sensual charms and sharp intellect and she bore him a son she named Caesarion. In 41 BCE Antonius had summoned the queen to be with him at Tarsus. ‘And when she arrived,’ writes Plutarch, ‘he made her a present of no slight or insignificant addition to her dominions, namely, Phoenicia, Coele Syria, Cyprus, and a large part of Cilicia; and still further, the balsam-producing part of Iudaea, and all that part of Arabia Nabataea which slopes toward the outer sea’. He joined her in Egypt later that year. The two eloped and a romance blossomed between the couple – and soon there were children. Despite being married to Caesar’s own sister Octavia, Antonius proceeded to marry Kleopatra in 36 BCE. His reason for doing so was to legitimize his children by the queen, the twins Alexander Helios and Kleopatra Selene; but it seemed to some observers that he was creating a new, rival empire to Rome’s, encompassing Egypt, Asia, Greece and the Near East.

Unfazed by his military setback, Antonius raised a new army. Failing to find willing Italian-born citizen recruits, he changed the enrollment rules, offering citizenship to any male willing to serve in his ranks and succeeded in creating five new legions. Antonius was elected consul with L. Scribonius Libo for 34 BCE, resigning it on the same day. He headed north and re-invaded Armenia as revenge for what he saw as Artavasdes’ treachery. Under the pretence of marching to war against Parthia, he arrived at the Armenian capital Artaxata and deposed the king. The Armenians resisted and elected the king’s son Artaxes. Antonius refused to accept the choice of new regent, arrested him and installed Artaxias, his half-brother, under the control of Canidius Cassius’ and a large contingent of Roman troops. Elated by his success, Antonius headed back to Alexandria where he celebrated a triumphal parade. It was the first to be held outside Rome and was seen by many at home as both against the laws of Romans and of Jove. Artavasdes and his family were among the trophies exhibited in the lavish spectacle in which Antonius dressed as Dionysos, wearing an ivy wreath upon his head, a gaudy saffron robe of gold and clasping a thyrsus (the sacred wand of the god) while Kleopatra accompanied him in the guise of Isis.