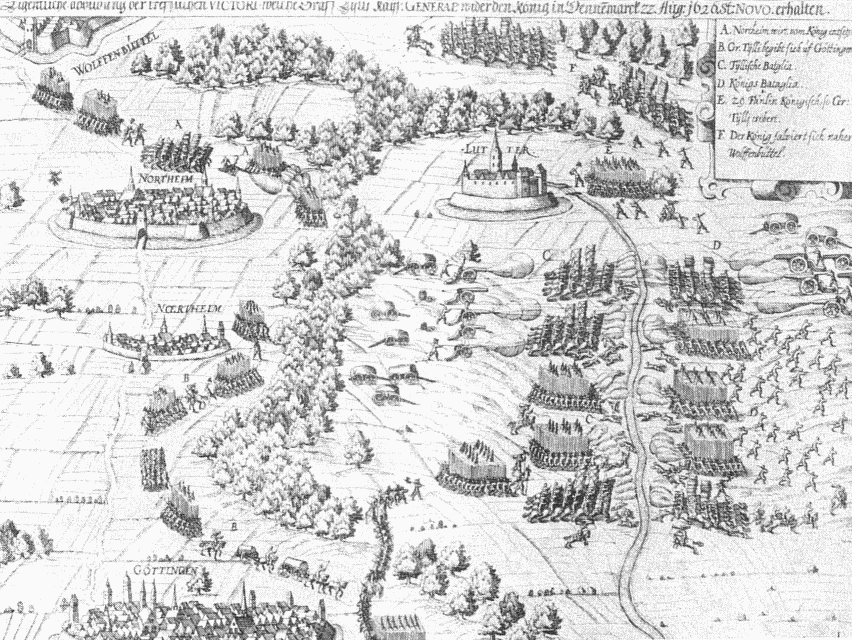

The latter had methodically reduced the three strongholds of Münden, Northeim and Goöttingen held by the Protestant forces between Lower Saxony and Hessen-Kassel. Münden was stormed in early July, losing between two- and four-fifths of its 2,500 inhabitants who were massacred as Liga troops plundered the town. Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly then brought in Harz miners to dig under the defensive ditch at Göttingen to drain the water from it. A relief force under the Rheingraf (Raugrave) Salm-Kyrburg was ambushed and scattered at Rössing on 27 July. Göttingen capitulated on 11 August 1626, having resisted for seven weeks. Danish King Christian IV hastened south to save his last garrison at Northeim, but failed to stop Johann von Aldringen joining Tilly with 4,300 Imperialists. The king retired north through Seesen on 25 August, intending to escape to Wolfenbüttel. His decision depressed Danish morale and revived Tilly’s flagging spirits. The Liga army harried the Danish retreat, cutting off parties left to delay its pursuit. King Christian faced the same dilemma as his namesake had at Höchst and Stadtlohn of whether to jettison his valuable baggage. He chose not to, and the wagons soon jammed the Wolfenbüttel road where it crossed thick woods north-east of Lutter-am-Barenberge. Christian was forced to deploy early on Thursday 27 August, hoping a more substantial rearguard action would dislodge the pursuit. Tilly had no intention of giving up and sought a decisive battle.

Both armies numbered about 20,000, though the Danes had a few more cannon. Their position lay in a cleared valley surrounded by forest. The recent hot weather had dried the Neile stream on the Danish right, though the Hummecke stream to their front and left appears still to have been wet. Tilly brought up his heavy guns, protected by musketeers, to bombard the Danes while the rest of his army came up around noon. His men ate lunch while the Danes waited uneasily in the rain. Johann Jakob, Count of Bronckhorst and Anholt opened the main action early in the afternoon by crossing the Hummecke and attacking the Danish left. Christian had gone ahead to disentangle the baggage train, without making it clear who commanded in his absence. Landgrave Moritz’s younger son, Philipp, made an unauthorized counter-attack in an attempt to silence the bombardment. Meanwhile, detachments sent earlier by Tilly worked their way through the woods to turn both Danish flanks. The Danes wavered around 4 p.m., enabling Tilly’s centre to cross the stream and capture their artillery. The Danish royal escort successfully charged to cover the retreat of the second and third lines, but the first was unable to disengage and had to surrender. Christian lost up to 3,000 dead, including Philipp of Hessen-Kassel, General Fuchs and other senior officers. Another 2,000 deserted, while 2,500 were captured along with all the artillery and much of the baggage, including two wagons loaded with gold. Tilly lost around 700 killed and wounded.

Christian blamed Duke Friedrich Ulrich who had withdrawn the Wolfenbüttel contingent four days earlier. The Danes burned 24 villages around Wolfenbüttel and plundered their way across Lüneburg as they retreated to Verden. The Guelphs negotiated the bloodless evacuation of Hanover and other towns, and assisted the imperial blockade of the Danes still holding Wolfenbüttel itself. The victory boosted Tilly’s prestige and enabled his beloved nephew Werner to marry the daughter of the wealthy Karl Liechtenstein. The Liga army swiftly overran the archbishopric of Bremen and sent a detachment into Brandenburg to encourage Georg Wilhelm to recognize Maximilian as an elector. However, Tilly’s troops were entering an area already eaten out by the Danes. Christian offered 6 talers to every deserter who rejoined his army and most of the 2,100 prisoners pressed into the Liga ranks promptly left. Weak and exhausted, Tilly’s troops could not deliver the knock-out blow. Conditions deteriorated over the winter, and the Bavarian Schönburg cavalry regiment took to highway robbery to sustain itself.

Mansfeld’s Last Campaign

Lutter prevented Christian sending aid to Count Ernst von Mansfeld who was now cut off in Upper Hungary. It is likely that Wallenstein deliberately delayed his pursuit until Mansfeld had gone too far to turn back. His gamble paid off, as Mansfeld was stuck in the Tatra mountains waiting for Bethlen, who was typically late. Despite the numerous exiles with his army, the Bohemian and Moravian peasants refused to follow the Upper Austrian example and remained loyal to the emperor. Those of Upper Hungary hid their harvest before Mansfeld and Johann Ernst of Weimar arrived. Mansfeld lost faith that Bethlen would appear and decided to cut his losses and dash across Bohemia to Upper Austria where the rising was still under way. Johann Ernst, though, still trusted Bethlen and thought Mansfeld’s plan too risky.

Wallenstein crossed Silesia in the second half of August and marched past his opponents to the Military Frontier where the Turks were harassing the forts. This show of force was sufficient to deter the pasha of Buda from helping Bethlen, who agreed a truce with the emperor on 11 November. Hardship, disease and desertion had reduced Mansfeld’s and Johann Ernst’s forces to 5,400. Having quarrelled with the duke, Mansfeld set out with a small escort intending to cross the mountains and escape to Venice. Though only 46, he was crippled by asthma, heart trouble, typhus and the advanced stages of tuberculosis. Insisting on standing up, he allegedly met his end fully armed when death caught him in a village near Sarajevo on 14 December. Johann Ernst died of plague just two weeks later.

Bethlen had waited until the harvest was in before advancing to meet Mansfeld with 12,000 cavalry and a similar number of Turkish auxiliaries. The latter had already left by the time Mansfeld reached Upper Hungary and Bethlen’s operations ran parallel with his talks with Ferdinand’s representatives. The truce was confirmed as the Peace of Pressburg on 20 December that accepted revisions to the Treaty of Nikolsburg in Ferdinand’s favour. The pasha of Buda had already suspended operations, and renewed the 1606 truce at Zsön in September 1627.

Bethlen remained untrustworthy; he offered his light cavalry to Gustavus Adolphus for his war against Poland, but died on 15 November 1629 before agreement could be reached. His erstwhile lieutenant, György Rákóczi, staged a coup in September 1630, displacing Bethlen’s widow Katharina who was negotiating to accept Habsburg overlordship. Transylvania was plunged into internal strife from which Rákóczi emerged triumphant in 1636 thanks to his closer ties to the sultan and the local Calvinist clergy.54

Many felt that Wallenstein should have defeated Bethlen rather than negotiate with him. Wallenstein defended himself against his critics at the Bruck conference in November 1626 and his extended visit to Vienna the following April, securing a free hand for the coming campaign. His success prompted Georg Wilhelm of Brandenburg to declare for the emperor. The elector had gone east to Prussia, taking only Schwarzenberg with him. Free from his Calvinist councillors in Berlin, he signed an alliance in May 1627. Winterfeld, the Brandenburg envoy who had worked indefatigably from 1624 to 1626 to forge a Protestant alliance, was arrested three months later on trumped-up charges of treason. The alliance allowed an imperial corps under Arnim across Brandenburg to Frankfurt on the Oder to trap the remnants of Mansfeld’s army holding out in the Silesian fortresses.

These had come under the command of Joachim von Mitzlaff, a Pomeranian in Danish service, who managed to rebuild the army to 13,400 and organize an effective base in the Upper Silesian mountains around Troppau and Jägerndorf. Wallenstein concentrated 40,000 men at Neisse in June 1627. As his fortresses surrendered one by one, Mitzlaff headed north with 4,000 cavalry hoping to dodge past Arnim. Wallenstein sent Merode and Colonel Pechmann after him, who caught and destroyed his detachment on 3 August. Mitzlaff escaped, but numerous Bohemian exiles were captured, including Wallenstein’s cousin Christoph whom he imprisoned. Wallenstein then marched north-west across Brandenburg towards Lauenburg, despatching Arnim northwards into Mecklenburg.

The mounting reverses encouraged Christian IV to resume negotiations. Ferdinand was known to be planning a conference to confirm the decisions of the Regensburg princes’ congress of 1623 as the basis for a general peace. He knew that the Palatinate and its Stuart backers would have to be included and accordingly welcomed an initiative from Württemberg and Lorraine to host talks at Colmar in Alsace in July 1627. Christian urged Frederick V to accept the emperor’s terms, since this would enable him to make peace without losing face. Frederick at last gave real ground, offering to renounce Bohemia, accept Maximilian as an elector, provided the title reverted to the Palatinate on his death, and to submit to imperial authority by proxy to avoid personal humiliation. Agreement was close since Ferdinand would probably have dropped his demand for reparations if Frederick had swallowed his pride and submitted in person. This was too much to ask, however, and the talks collapsed on 18 July.