Dewey’s next task was to concentrate the fleet. When he arrived in Japan in January, the handful of ships belonging to what was rather grandly titled the American Asiatic Squadron was scattered all over the western Pacific: in Korea, in Japan, and along the China coast. If it came to war, as Dewey surely expected, this would not do. Consistent with the Mahanian prescription that fleet concentration was the key to victory, Dewey sent out orders for all the vessels to concentrate at Hong Kong, and as soon as he loaded the ammunition brought by the Concord, he set out with the Olympia and Concord for the British crown colony on the South China coast.

News of the destruction of the Maine was waiting for Dewey when the Olympia arrived at Hong Kong on February 17. All over the harbor, the ships of a dozen nations had lowered their flags to half staff in recognition of the disaster, and throughout the following days, boats plied back and forth across the harbor as representatives of the various squadrons delivered the formal condolences of their nations to the American visitors. Much like the international response to the September 11, 2001, disaster, the world reaction in 1998 was “horrified amazement at such an act.”

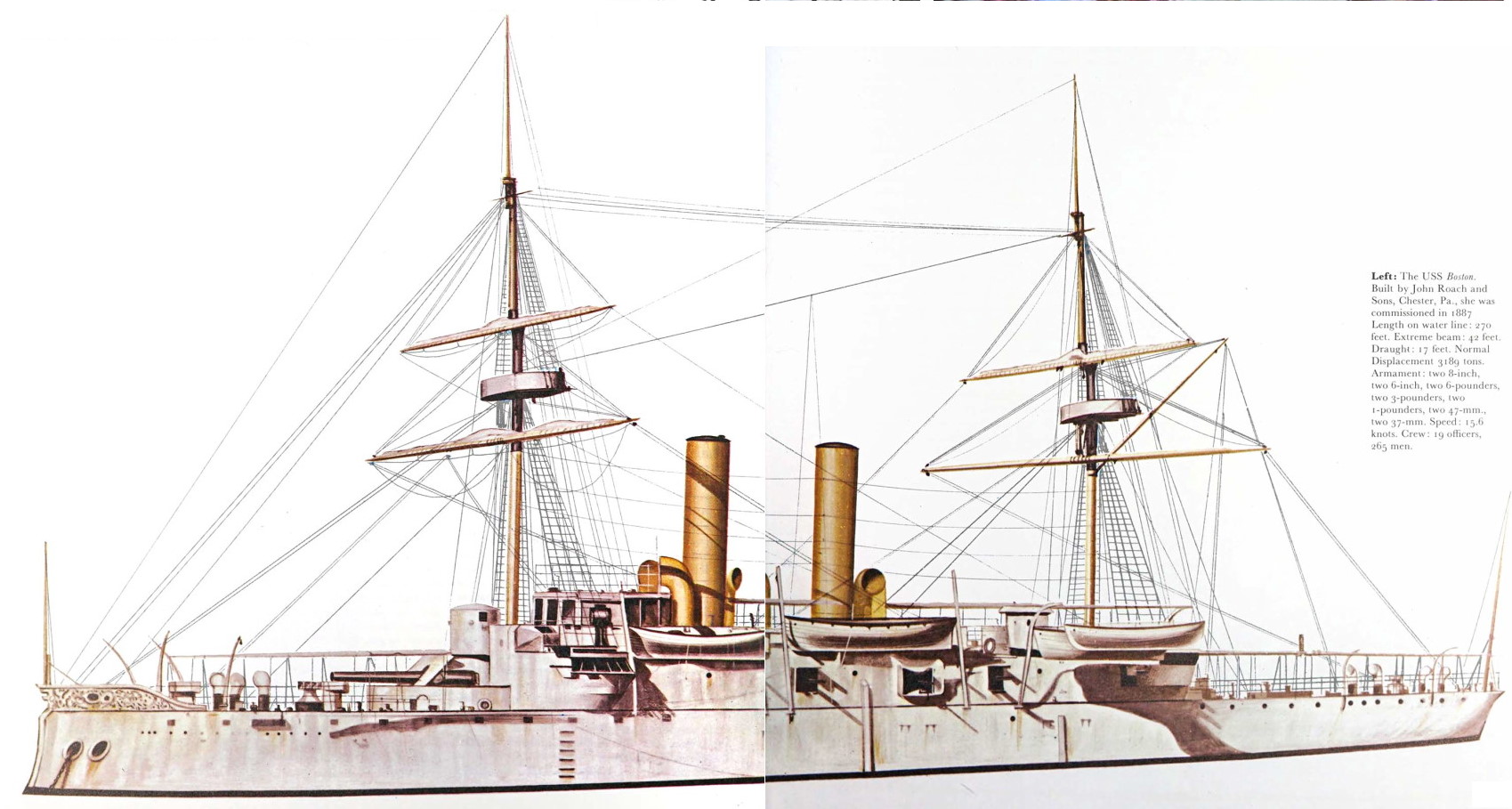

Meanwhile, other U.S. vessels arrived to augment Dewey’s squadron, including the veteran cruiser Boston, a dozen years old now but armed with eight-inch guns, and the newer but smaller Raleigh, with six-inch guns. Most welcome of all was the Baltimore, another eight-inch-gun cruiser that originally had been dispatched as a replacement for the Olympia but which in the new circumstances would join the American squadron as a reinforcement. Equally important, the Baltimore brought with it enough ammunition to bring the ships of the squadron up to about 60 percent of capacity. This was probably sufficient even for a large-scale battle, but Dewey’s awareness that his ships did not have a full complement of ammunition and that there was no source of resupply closer than California remained a nagging worry in the back of his mind.

The most serious of Dewey’s logistical problems concerned fuel. The Americans had no naval bases in the Far East and were therefore dependent on the hospitality of the Japanese at Yokohama or the British at Hong Kong. In the case of war, even those bases would be closed to them, since international law forbade neutrals from allowing belligerents to operate from their ports and harbors. Lacking an American naval base in the Far East, Dewey’s steam-powered ships would have no place where they could recoal. The solution, though not a perfect one, was somehow to acquire a number of coal ships, or colliers, to provide floating logistic support. Dewey cabled Secretary Long for permission to purchase both coal and a collier to carry it. Long approved the request and suggested that Dewey might purchase the British Nanshan, due any day in Hong Kong with a cargo of Welsh coal. Dewey did so, and he also purchased the British revenue cutter McCulloch and the small supply ship Zafiro. All three vessels became U.S. auxiliary warships, but although Dewey put a U.S. Navy officer and four signalmen on board each vessel, he kept their original English crews and registered the ships as merchant vessels so that they would not have to leave Hong Kong with the rest of the squadron when war was declared. To sustain the deception, Dewey filed papers listing Guam in the Spanish Ladrones as their official home port, an island that was then so remote it was, as Dewey said, “almost a mythical country.”

Dewey also had to resolve some personnel problems within the officer corps. Two of Dewey’s senior officers, Captain Charles V. Gridley of the Olympia and Captain Frank Wildes of the Boston, were due to rotate back to the States. Both men begged Dewey to be allowed to stay with their commands until after the fight. Having spent a lifetime in a peacetime navy, neither wanted to miss the one chance they were likely to have for martial glory. Dewey was sympathetic; he allowed Gridley to stay in command of the Olympia despite his precarious health, and he asked Captain Benjamin P. Lamberton, who had orders to take command of the Boston, if he would instead accept an appointment as chief of staff on the flagship. Finally, there was the problem of what to do with the old monitor Monocacy, relic of a former age. Aware that the Monocacy would be of little value in a fight with the Spanish, Dewey decided to leave it in Shanghai under a skeleton crew, and he distributed the rest of the men to fill out the crews of his other ships, bringing her skipper, C. P. Rees, onto the Olympia as the flagship’s executive officer. Another addition to the Olympia’s wardroom was Joseph L. Stickney, a Naval Academy graduate who had resigned his commission to become a journalist. He asked Dewey for permission to accompany the squadron into battle. Dewey not only agreed, he made Stickney a volunteer aide, and Stickney was therefore present on the bridge of the Olympia throughout the campaign, making him an early embedded journalist.

Dewey had already completed most of these dispositions when he received a cablegram from Roosevelt that confirmed most of his decisions: “Order the squadron, except for Monocacy, to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands. Keep Olympia until further orders.”

Dewey labored daily to ensure that the assembled squadron was ready for combat. He had the ships scraped and painted, covering their traditional peacetime white with an equally traditional drab gray-green that the sailors called “war colors” and which the Spanish later referred to as “wet moon color.” When Lamberton arrived in Hong Kong aboard the small steamer China, he had been out of touch with unfolding events during the long Pacific crossing. As he peered ahead into Hong Kong Harbor through a lifting fog and saw the American squadron at anchor, he cried out to a fellow passenger: “They’re gray! They’re gray! That means war!”

All of these preparations had to be conducted in the open; there were no secrets in the roadstead at British Hong Kong. Most of the British openly sided with their American cousins, but despite that sympathy, international law compelled the British to ask Dewey to leave as soon as the United States became a formal belligerent. On April 24 Dewey received a formal message from the governor general of Hong Kong, Major General Wilsone Black, who notified him that he would have to stop taking on coal and stores in Hong Kong and leave port by four the next afternoon, though in a private note, Black confided: “God knows, my dear Commodore, that it breaks my heart to send you this notification.”

By this time, the Americans had completed most of their preparations and Dewey had already decided to quit Hong Kong and take his fleet to Mirs Bay, some thirty miles up the coast. Mirs Bay was indisputably Chinese territory, but in 1898 the notion of Chinese sovereignty was little more than an abstraction. Dewey believed—correctly, as it proved—that he could anchor his squadron there without fear of “international complication.” The same day he received Black’s notice, therefore, Dewey sent his four smaller ships to Mirs Bay and planned to follow them the next day with the rest of the squadron. He used the extra day to complete the scraping and painting of the Baltimore and to make engine repairs on the Raleigh. Ensign Harry Chadwick would be left behind with the chartered tug Fame to accept delivery of a new circulating pump for the Raleigh and to bring the latest information about the Spanish squadron in the Philippines. That night, one of the British regiments hosted the American officers at a farewell dinner, and afterward one British officer remarked lugubriously: “A very fine set of fellows, but unhappily we shall never see them again.” At ten the next morning, six hours in advance of the British deadline, the American squadron steamed slowly out of Hong Kong harbor as British sailors manned the side in a gesture of silent support, and patients on the British hospital ship offered up three rousing cheers, which were answered by the Americans.

Safely anchored in Mirs Bay, Dewey ordered that the ammunition brought by the Baltimore be distributed to the ships of the squadron, and he kept the crews busy day and night preparing for battle. A few of the ships were shorthanded. Like most nineteenth-century navies, the U.S. Navy accepted sailors of virtually any nationality. In addition to native-born Americans, about 20 percent of the crew consisted of Englishmen, Irishmen, Frenchmen, Chinese, and others. On the eve of the departure from Hong Kong, a handful of these foreign nationals had disappeared. The rest, however, worked with a will. They tore off the decorative gilt woodwork and threw it over the side so that wooden splinters would not add to the casualties, though on the Olympia, Dewey merely ordered the woodwork covered with canvas and splinter nets. Sailors also kept busy constructing makeshift barricades of iron to protect the ammunition hoists and draping chains over the sides to add another layer of “armor” to otherwise unarmored areas. In the midst of all this activity, on April 27 officers on the Olympia saw the little tug Fame enter Mirs Bay at top speed, its whistle blowing shrilly, and soon a grinning Ensign Chadwick was on the quarterdeck delivering a cablegram from Secretary Long: “War has commenced between the United States and Spain. Proceed at once to Philippine Islands. Commence operations at once, particularly against the Spanish fleet. You must capture vessels or destroy. Use utmost endeavors.”

Even without the two references to acting “at once,” Dewey planned to waste no time. He ordered the signal for “all captains,” and within the hour he was meeting with his senior officers. He gave no fiery speeches such as those offered by Perry and Buchanan before their battles. Instead he explained the squadron’s mission quietly and dispassionately, and after a businesslike meeting he dismissed them to their ships. At 2:00 that same afternoon the nine vessels of the American Asiatic Squadron hoisted their anchors and shaped a course for the Philippine Islands.

Six hundred and thirty miles to the south, Rear Admiral Don Patricio Montojo y Pasaron was contemplating his alternatives, none of which looked particularly good. Montojo had been in the Spanish navy for forty-seven years, having obtained his commission three years before Dewey had entered the Naval Academy at Annapolis. He was a proud man who loved his country, but he was sufficiently realistic to appreciate that his aging squadron of two small cruisers and five gunboats had virtually no chance against the newer, bigger, and faster American warships. From the start, therefore, it was evident to him that his role was not so much to win as it was to lose honorably, and if possible heroically. Three years earlier, in contemplating a war with the United States, the Spanish governor general of Cuba had declared that “honor is more important than success,” and that could well have stood as Montojo’s motto.

Unlike Dewey, Montojo had a secure base from which to operate, and that should have given him a significant advantage, but no one in the Spanish chain of command, from the governor general on down, seemed willing to undertake the kind of energetic measures necessary to prepare for the coming fight. The correspondence from the Ministry of Marine and the governor general was characterized more by banal generalities than realistic planning. They proclaimed their confidence that Montojo would do his best without ever suggesting what that might involve. Typical of such documents was a broadside penned by the archbishop of Manila that was intended to inspire resistance to the pending American attack. He referred to the United States as a country “without a history” whose leaders were men of “insolence and defamation, cowardice and cynicism.” Such a country dared to send “a squadron manned by foreigners, possessing neither instruction nor discipline . . . with the ruffianly intention of robbing us” and forcing Protestantism on a Catholic population. Such swaggering fatuousness not only failed to inspire resistance, it gave the Americans increased determination, since a copy of it found its way to Hong Kong and eventually to Dewey, who had it read aloud on board each of the American vessels during the transit from Mirs Bay, provoking predictable vows of revenge.

Montojo was equally complicit in the general malaise, offering little guidance to his subordinates beyond a general instruction to “do everything possible to guard the honor of the flag and the navy.” Whether from conviction or fatalism, the Spanish leadership clung to the notion that the old values of personal bravery and heroic behavior would be sufficient to overcome the technological advantages of America’s “New Navy.”

Even if the Spanish had been more focused in their preparations, it would probably have made little difference, for Montojo’s ships were hopelessly overmatched. His newest and biggest vessel was the 3,500-ton cruiser Reina Cristina, whose six 6.2-inch guns were the largest in the Spanish squadron, but which could be easily outranged by the eight-inch guns on the Olympia, Boston, and Baltimore. Montojo’s second largest ship was the much older 3,260-ton Castilla, which was built partly of wood, had no armor, and had ancient engines that had broken down completely. Her carved and gilded woodwork gleamed in the sunlight, but she was, in fact, no more than a floating battery that had to be towed from place to place. The rest of his squadron consisted of five small gunboats of just over a thousand tons each, none of which had a gun larger than 4.7 inches.

Early on, Montojo concluded that if he had any chance at all, it was to fight the Americans from the protected anchorage at Subic Bay, some thirty miles up the coast from Manila.† As war clouds gathered following the explosion of the Maine in February, he ordered that four 5.9-inch guns originally intended for Sangley Point near the Cavite Navy Yard in Manila Bay be sent instead to Subic Bay and installed there to provide support for the fleet in case the Americans attacked. He placed this crucial duty in the hands of Captain Julio Del Rio, but, having given the orders, he did not bother to follow up on them or exercise any personal oversight, and predictably the work lagged. On the very day that Dewey left Hong Kong for Mirs Bay, Montojo took his own squadron to sea, steaming out the Boca Grande and then turning north along the coast of Bataan for the anchorage at Subic Bay, the Castilla towed by the transport Manila. En route, the Castilla began taking on water through her propeller-shaft bearing, and her crew had to fill the bearing with cement. That stopped the leak, but it also ensured that her engines would never work again.

When Montojo arrived at Subic Bay he learned “with much disgust” that none of the four guns he had sent there had been mounted and that no mines had been laid. Very little at all, it seemed to him, had been done to prepare for the coming fight. For a few hours he nursed the hope that it might still be possible to complete the work before the Americans arrived, but the very next day he learned that the Americans had left the China coast and were already en route. Confronted with this reality, Montojo called a council of war on board the Reina Cristina, where to a man his captains voted to return to Manila Bay and fight the Americans there. It is a measure of Spanish fatalism that the decisive argument in this discussion was that the water in Manila Bay was shallower than it was at Subic, so when the Spanish ships were sunk, the crewmen would have a better chance of surviving. With such logic ruling the day, Montojo resignedly led his squadron back to Manila Bay, where it arrived late on April 29, one day ahead of the Americans.

At Manila, Montojo assessed his few remaining options. One—undoubtedly his best—was to anchor his fleet under the walls of the city of Manila. A sprawling metropolis of some three hundred thousand, Manila sat on a coastal plain where the Pasig River flowed into the bay, and it was well fortified on both its landward and seaward sides by fifty-foot-thick masonry walls thirty to forty feet high. Atop those walls were a total of 226 heavy guns. Most of them were old muzzle-loaders of little practical use against modern ordnance, but there were also four 9.4-inch rifled guns, two of which faced the bay. They were the biggest guns in the theater and could outrange even the eight-inch guns of the Americans. If Montojo wanted to even the odds between his ornate but elderly cruisers and Dewey’s more modern armored ships, his best bet was to anchor under the guns of the city. But that would mean that overshots from the American fleet would land in the city itself, with the result that hundreds, maybe thousands, of civilians would die. Montojo, therefore, rejected the idea. “I refused to have our ships near the city of Manila,” he wrote, “because, far from defending it, this would provoke the enemy to bombard the plaza.”

Montojo’s second option was to fight a battle of maneuver with the Americans. But there was no hope that this ploy would be successful: the Castilla could not move at all, and even the fastest of the Spanish ships was slower than the slowest American vessel. His only remaining option, then, was to fight from anchor, and if he could not (or would not) do so from Manila, his only other chance was to anchor his fleet near the Cavite Navy Yard, on the southern edge of the bay, where two 5.9-inch guns and one 4.7-inch rifle could add their weight to the coming fight, though only one of the 5.9-inch guns faced the bay.

Montojo anchored his seven ships in the traditional line-ahead formation stretching out in a gentle curve from Sangley Point, which enclosed Bacoor Bay on the southern shore of Manila Bay. He moored several lighters filled with sand alongside the immobile Castilla to give that unarmored vessel some protection, ordered the topmasts taken down, removed the ship’s boats, had the anchors buoyed, and all in all prepared his doomed command for combat. As he made these preparations, the telegraph brought the news that the Americans had stopped to look into Subic Bay and, finding nothing there, had shaped a course for Manila. The day passed with no further news, but then at midnight Montojo heard the sound of gunfire from the Boca Grande as Dewey’s squadron ran into the bay. It would be only a matter of hours now. “I directed all the artillery to be loaded, and all the sailors and soldiers to go to their stations for battle.”

It was 5:00 A.M. and the sun was rising above the hills behind Manila when the American cruisers arrived off the city. Dewey had not moved from his position on the Olympia’s starboard bridge wing, and as he surveyed the waterfront, it was evident even without the reports from the lookouts that the Spanish fleet was not there. The Manila batteries opened fire from long range, most of the shots falling well short, though one of the shells from a 9.4-inch gun landed directly in the wake of the Olympia as it steamed past. Boston and Concord replied with two eight-inch shells each, which landed near the Spanish batteries, but it was little more than a gesture, since Manila was not Dewey’s target, and in any case he wanted to husband his ammunition. As the sun spread its light across the “misty haze” of the bay, lookouts on the Olympia spotted “a line of gray and white vessels” four miles to the south anchored in “an irregular crescent” off Sangley Point, near Cavite Navy Yard. Dewey immediately ordered the Olympia to turn toward them and increase speed to eight knots. The Baltimore, Raleigh, Concord, Petrel, and Boston all followed in the Olympia’s wake, large battle flags flying from every masthead, and with bands playing patriotic airs on at least two of the ships. The three transports remained behind, beyond range of the Spanish guns, but close enough to tow crippled ships out of the battle line if necessary.

Dewey’s battle plan was a simple one. The Olympia would lead the American warships past the Spanish vessels, each firing in turn, and then it would circle back to pass the enemy again on the other tack. He was determined to come as close to the Spanish as he could without running aground. He remained concerned about his squadron’s limited ammunition and wanted to make sure that every shot counted. The Americans had a chart of the bay, and it showed plenty of deep water up to within two thousand yards of the Spanish position, but Dewey was taking no chances. From the Olympia’s bluff bow, a leadsman regularly hurled a weighted line out in front of the ship, reeled it in after it struck bottom, and called out the depth of water under the hull.

At a few minutes past five, the Spanish battery on Sangley Point opened fire, though the shots fell well short. The Spanish had a virtually unlimited supply of ammunition and could afford to be wasteful. Dewey held his fire. Still attired in his dress white uniform, the constricting collar buttoned up to the chin, Dewey was the very picture of stoicism, though others on the Olympia had made pragmatic adjustments to their clothing. The gunners had stripped to the waist in the tropical heat, and they stood silent in the tension-filled run-up to battle. One participant recalled that there was no sound but for the steady chunk, chunk, chunk of the engines and “the monotonous voice of the leadsman.” Down below, in the engine room, the stokers fed the fires, ignorant of what was happening topside except for infrequent updates shouted down to them by thoughtful sailors. They had been allowed a break at 4:30 A.M., but once the action began they would remain “shut up” in their “little hole” until the battle was over.

At about 5:15 the Spanish ships opened fire, the 6.2-inch guns of the Reina Cristina throwing up large plumes of water in front of Olympia, the shells landing closer now, but still well short. The American ships remained silent for another fifteen minutes—a passage of time that seemed like hours to the waiting gunners. Finally at about 5:40, with the two fleets nearly parallel to one another and about five thousand yards apart (two and a half nautical miles), Dewey turned to the Olympia’s captain and said laconically: “You may fire when ready, Gridley.” Gridley passed the order, and the eight-inch guns of the Olympia’s forward turret spoke. Immediately the guns on every U.S. ship opened as well. A witness on the Olympia recalled that the Americans poured out “such a rapid hail of projectiles” that it seemed to him that “the Spanish ships staggered under the shock.” Down below in the Olympia’s engine room, the stokers were aware that the battle had been joined at last. “We could tell when our guns opened fire by the way the ship shook,” recalled stoker Charles H. Twitchell. “We could scarcely stand on our feet, the vibration was so great. . . . The ship shook so fearfully that the soot and cinders poured down on us in clouds.”

Like the battles on Lake Erie and at Hampton Roads, the Battle of Manila Bay was a gun duel. Neither mines nor torpedoes played any important role in the fight, nor did any of the opposing warships get close enough to ram one another. Early in the battle, two small vessels came out from behind the main Spanish battle line, and one of them steamed toward the Olympia with apparent hostile intent. The Americans concluded that it was a torpedo boat bent on a suicide mission. A hailstorm of American shells sank it, and the other vessel turned back and ran itself aground near Sangley Point. Except for that, both sides relied exclusively on gunfire. The American ships cruised slowly past the Spanish battle line, the guns of the port side battery firing as fast as the gunners could load them, both sides firing at will.

When the entire fleet had passed, Dewey ordered the Olympia to make a 180-degree turn to port and retrace the same course back again, this time a little closer to the target and with the starboard batteries firing. His plan was to run back and forth in a figure-eight pattern in front of the Spanish fleet, moving closer at each pass and firing alternately from the port and starboard batteries until the Spanish surrendered or were destroyed. The noise was tremendous, and visibility was soon significantly limited due to the clouds of smoke that roiled up from the opposing battle lines. Both sides were using black powder, which generated great clouds of white smoke. That, mingled with the black smoke from the funnels of the American ships and the mist of the morning fog, enshrouded the scene of battle with a smoglike haze. From a range of nearly two miles, it was hard to tell what effect, if any, the guns were having. Near misses sent geysers of water onto the decks of the American vessels, overhead wires and signal halyards were sheared, and a few shells actually struck the American ships, though none of them found a vital target.

For the most part, the Spanish remained anchored in their stationary battle line. At one point, Montojo’s flagship, the Reina Cristina, made a short-lived effort to come out and attack the Americans, more, perhaps, for the sake of honor than because it promised any tactical advantage. But as soon as the Reina Cristina moved from its anchorage, it became the target of every gun in the American squadron and was battered by a number of hits, including one from an eight-inch shell that tore through the vessel bow to stern, killing a score of men and wrecking the ship’s steering gear. Afire in two places, the Cristina ran aground off Sangley Point, and Montojo shifted his flag to the Isla de Cuba.

Showing no concern for the scarcity of ammunition, the American gunners loaded and fired as fast as they could. The routine of firing the big naval guns had changed a bit in the three and a half decades since Hampton Roads. One change was that the guns were now loaded at the breech rather than at the muzzle. After each round, it was the responsibility of the gun captain to unlock and throw open the breech block. He then stood aside while others washed off “the powder residue from breech block and the bore” and shoved another round of shell and powder into the chamber. The second captain then closed and locked the breech “with a heavy clang,” put in a new primer, and reported the gun ready. But at this point, the routine reverted to the time-honored practice of navies past. As a contemporary noted, “each gun was loaded and fired independently,” and it was up to each gun captain to select a target, determine the range, aim, and fire his weapon.

As in the Age of Sail, the gun captains at Manila Bay leaned over the gun barrel, sighting with the naked eye. The difference was that now they sighted on a target that was as much as two miles or more away. Determining the range to the target was a matter of sighting on cross bearings while glancing at a chart. Though the target was motionless, the U.S. ships were under way, and as a result each gun captain had to wait for the target to pass across his line of vision. At the same time, the American ships were also rising and falling as they responded to the gentle swell in the bay, and the target therefore swam before the gunner’s eyes, moving up and down as well as right to left. As each gun captain watched and waited for the right moment, he called out a series of orders to the men of the gun crew, who trained the gun to the right or left using a series of hand wheels connected to gears. “Right!” he would call out as the target moved across his line of sight, then perhaps as the result of a slight shift in the helm of his own vessel, he would shout, “Left!” Finally, when “the line of sight strikes the target,” the gun captain would jump aside and yank the lock string in his hand. At once there was “a thunderous crash” and a great “stifling cloud of smoke,” and the gun’s recoil sent it flying backward “as if it were a projectile itself.” But thanks to a hydraulic cylinder, it quickly slowed and stopped, and the whole process started over again as the gun captain flung open the breech block to receive the next round.

It is not surprising that American marksmanship was terrible. One American officer admitted candidly that “in the early part of the action, our firing was wild.” Lacking any more effective way to determine the range or aim the guns except by line of sight, hitting a target at five thousand yards was more a matter of luck than skill. The fact was that the range of the naval guns had outstripped the ability of the gunners to put their ordnance on target. On Lake Erie, and especially at Hampton Roads, the gunners had fired into targets so close they could hardly miss, even with smooth-bore iron cannon. On Manila Bay, the rifled steel guns dramatically increased the range, but without any way to coordinate the fire or put the guns on target, most of the shots flew high or wide. Moreover, firing by ricochet, skipping the shells across the surface of the water as the ironclads had done at Hampton Roads, was no longer practical; a gunnery officer on the Olympia noted that although direct hits were difficult, “ricochet effects were worthless.” He recalled a sense of “exasperation” as he noted “a large percentage of misses from our well-aimed guns.”

It was hot work—literally as well as figuratively. The men at the guns had stripped off their shirts even before the action had begun, and they fought now with their heads bound up in water-soaked towels. Those who served in the steel-jacketed gun turrets, where the air was stagnant and the heat all but unbearable, stripped to their undershorts, a few keeping on only their shoes to prevent their feet from burning on the hot deckplate. Down below in the engine room, where the temperature neared two hundred degrees, it was so “unbearably fierce at times,” one stoker recalled, that “our hands and wrists would seem on fire, and we had to plunge them in water.” The oppressive conditions did not stifle enthusiasm. On the Raleigh, a junior officer went down into the fireroom to check on the stokers and found the men singing “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” as they worked. On the Olympia, however, three of the stokers passed out from the heat and had to be hoisted unconscious up to the deck.

After the third pass, the Americans had come to within two thousand yards (one nautical mile) of the Spanish battle line. From this range, the American guns should have been doing serious damage, and in fact they were. But that was not immediately evident to the knot of senior officers watching from the bridge of the Olympia. As one of them reported later, “At that distance in a smooth sea, we ought to have made a large percentage of hits; yet, so far as we could judge, we had not sensibly crippled the foe.”

Though Dewey’s stoic expression never changed, he was growing increasingly worried. If the Spanish fleet remained intact after the Americans fired off all their ammunition, it would not matter if his own ships remained substantially unhurt; he would have to abandon the contest and withdraw. The Olympia had been hit five times already, one shell striking the hull just below the bridge where Dewey was standing, though by fate or by chance none of those shells had done any serious damage. But Dewey did not know the condition of the other vessels in the American squadron. As far as he knew, they had suffered grievous casualties, and the Spanish ships continued to fire defiantly. One American officer noted that “the Spanish ensigns still flew and their broadsides still thundered.” An American sailor wrote simply that “they fought like beasts at bay.” By the time the American ships began their fifth pass, just after 7:00 A.M., there were still “no visible signs of the execution wrought by our guns.”

Then at 7:35, after two hours of battle, Gridley approached Dewey with a startling piece of information. He had just been informed that the Olympia had only fifteen rounds of five-inch ammunition left. Fifteen rounds could be fired away in a matter of minutes. The Olympia would still have her four big guns, but without the five-inch guns, its rate of fire would fall off dramatically. And if the five-inch ammunition was so badly depleted, how long before the eight-inch ammunition began to run out? This was the scenario Dewey had feared most. His ships would be out of ammunition, with no way of getting any more, in the face of a still-defiant Spanish fleet possessed of unlimited quantities of ammunition and ready for battle. He would be helpless. “It was a most anxious moment for me,” he later recalled. “So far as I could see, the Spanish squadron was as intact as ours. I had reason to believe that their supply [of ammunition] was as ample as ours was limited.” He saw no option but to call off the fight and withdraw out of range in order to redistribute ammunition among the ships and perhaps reassess the situation. He ordered the fleet to “withdraw from action.”

The Olympia turned away from the roiling smoke and led the American squadron off toward the center of the bay. Though he retained his characteristic impassive expression, his mood was dark. A volunteer officer on the bridge wrote later: “I do not exaggerate in the least when I say that as we hauled off into the bay, the gloom on the bridge of the Olympia was thicker than a London fog in November.” Ironically, while the mood on the bridge reflected disappointment and despondency, the men at the guns were upbeat and optimistic. The embedded journalist, Acting Lieutenant Joseph Stickney, while making the rounds of the ship, was stopped frequently by the smoke-blackened gunners, who wanted to know why they were breaking off the action. Not wanting to depress their obviously high morale, he told them that “we were merely hauling off for breakfast.” When Stickney returned to the bridge and reported what he had said to Dewey, the commodore replied that he could give any reason he wanted except the real one.

But Dewey’s dark mood soon improved. Once the fleet had hauled off and some of the battle smoke lifted, it became evident that the Spanish fleet had been considerably damaged after all. He could see flames rising from both of the Spanish cruisers, and occasional muffled explosions aboard both ships indicated that they had been badly hurt, perhaps fatally so. Then Dewey got even better news. It turned out that the previous report about the scarcity of ammunition had been in error. It was not that there were only fifteen rounds left; rather, only fifteen rounds had been expended! There was plenty of ammunition left, more than enough to continue the battle and finish off the Spanish fleet. Dewey needn’t have broken off the battle at all, for he was clearly winning. Having done so, however, he now issued the order for the crews to go to breakfast and for commanding officers to report their casualties. He still did not know how much damage his own squadron had suffered.

As the American captains came aboard, one by one, they reported the absence of any casualties. Most of them offered this information diffidently, even apologetically. Raised in the age of wooden ships and iron men, they had become accustomed to the notion that the heroism of a ship’s crew could be measured by its butcher’s bill of killed and wounded. Perry’s victory on Lake Erie had been particularly glorious in part because the casualties had been so heavy. Now each of Dewey’s captains reported that they had suffered no fatalities—none at all—and no serious damage to their ships. The ship that had suffered the most damage was the Baltimore. Montojo had incorrectly identified her as a battleship and had ordered his gunners to concentrate on her. In consequence she had been hit six times, though not seriously. Indeed, the hand of Providence seemed to have guided the flight of some of the shells. In one case, a five-inch armor-piercing shell had passed through two groups of sailors on the Baltimore without hitting any of them, struck a steel beam, and was deflected upward through a hatch cover, hitting the recoil cylinder of the port six-inch gun. Then it fell to the deck, where it spun like a top before it finally skittered over the side, all without exploding. The Boston had been hit four times, and one 6.2-inch shell had exploded in the officers’ wardroom, but since the room had been unoccupied at the time, there had been no injuries.

It was all right, then. The ships of the American squadron were uninjured, there was plenty of ammunition on hand, and the Spanish fleet was seriously damaged. As soon as the men had a chance to grab something to eat, Dewey could renew the action and finish the job. The sailors munched away happily, though many of them passed up the opportunity to eat in order to grab a few moments of sleep. The breakfast laid out by the stewards in a corner of the officers’ wardroom went largely untouched. One reason, perhaps, was that the sardines, canned beef, and hardtack lay on the same table as the surgeon’s knives, saws, and probes, since the ward-room served as the surgeon’s cockpit during battle stations. All this time, fires continued to burn out of control on the Spanish ships, and even from a dozen miles away, the men on the American vessels could hear “frequent explosions” from deep inside the hulls of their adversaries.

The second round of fighting began at 11:15. By now there was no doubt left about the outcome. The Baltimore led the American battle line, which closed to within less than two thousand yards to finish off the badly crippled Spanish vessels, all but a few of which had retired behind Sangley Point. Spanish fire was slow, irregular, and inaccurate, and the few vessels still able to resist at all fired only about a dozen shells while being pounded by the American warships.

If American casualties were minimal, Spanish casualties were horrific. The grounded Reina Cristina was hit seventy times, and out of a complement of 493 men, some 330 were either dead or missing and another 90 had been wounded—a casualty rate of over 80 percent. The unarmored Castilla, her wooden hull still painted peacetime white, burned out of control. The Don Antonio de Ulloa continued to fight until she sank at her moorings, colors still flying. The shore batteries, too, were soon silenced, and white flags were raised above their parapets. By noon it was all over: white flags flew above the batteries ashore, and virtually all the Spanish vessels were on fire or sinking.

Dewey sent the Petrel into Bacoor Bay to secure the prizes. The Petrel was the only American vessel with a shallow enough draft to enter the bay, and there were a few anxious moments as the little gunboat ran into the bay unsupported. Her commander, Lieutenant Edward M. Hughes, sent the ship’s two whaleboats inshore to round up the few undamaged small boats as prizes and set fire to the abandoned hulks that were not already burning. There was no resistance, and Hughes signaled the main fleet: “The enemy has surrendered.”

After that, the Olympia, Baltimore, and Raleigh steamed slowly northward for Manila, where the American ships dropped anchor off the city as if they were making a routine port visit. The heavy guns of the city’s battery, which had kept up a desultory fire all morning, were now silent. Dewey dropped anchor well inside their effective range and sent Consul O. F. Williams ashore to inform the Spanish governor general that any fire against American vessels from those guns would compel Dewey to bombard the city. The governor agreed at once to a cease-fire.