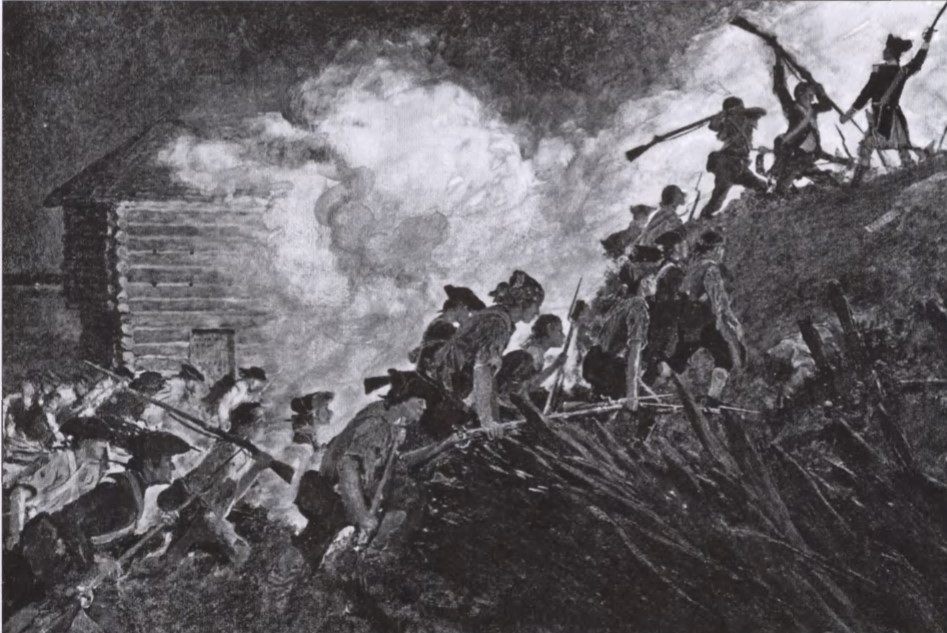

Powder soaked but ferocity unabated. Lee’s picked force of dismounted dragoons takes advantage of the garrison’s confusion to force the drawbridge at Paulus Hook with clubbed muskets and the bayonet. The British had previously sent out a foraging party of their own, for whom Lee’s advancing force was mistaken – with disastrous results.

The British grip on New York, won at a staggering cost to the Americans in a series of battles in late 1776, remained a hindrance and a threat to the Continental cause until the final British withdrawal in November of 1783. British vessels of war prowled up the Hudson as far as the great American bastion of West Point, while soldiers and supplies took advantage of Manhattan’s superb harbour and transportation system.

Neither Washington nor his subordinate commanders were willing to leave matters as they stood. The isolated British and Loyalist bastion across the Hudson allowed the British to control access to the river, but it also offered an inviting target. ‘Light Horse Harry’ Lee’s brilliantly successful raid on the outpost at Paulus Hook kept the British nervous and uncertain in the very heart of their strongest position in their former colonies.

The British in the American War of Independence sought to employ Alexander’s strategy in Afghanistan – immobile forces scattered in penny packets across the disputed territory. Such outposts certainly restricted the movement of American rebels in the northern colonies, but they also enabled a mobile force that had amassed temporary superiority to swoop in – with disastrous results at Paulus Hook. For any organization to take advantage of an opportunity or to respond to an onslaught, information is as vital a factor as mobility – and mobility allows the transmission of vital news and a prompt response to it. The role of horsemen in battle is as much to prevent intelligence of their side’s actions as it is to acquire knowledge of the position, strength and intentions of the enemy. Henry Lee (1756-1818) dismounted his dragoons at Paulus Hook for a sudden descent on his target garrison – while screening forces along the roads stood ready to limit British awareness of his raid.

Battle of Paulus Hook: 19 August 1779

George Washington appreciated the value of intelligence, and ran a sophisticated espionage network that kept him aware of British movements and vulnerabilities, much to the profit – and survival – of his cause. The advantages offered by mounted soldiers were too obvious to be ignored, and by the summer of 1779 there were enough rebels on horseback to become a considerable part of the strategic equation.

Bloody Ban

Two earlier incidents in the war show the versatility of the mounted combatant. Lieutenant-Colonel Banastre ‘Bloody Ban’ Tarleton (1754-1833) of the 1st Dragoon Guards was perhaps the finest British cavalry officer of the war: skilled, resourceful and legendarily ruthless. His favoured use of his troopers’ mobility was to spread terror and anxiety throughout the rebellious colonies. More than one incident prompted the phrase ‘Tarleton’s Quarter’, meaning that prisoners would not be spared. Luck enhanced his reputation: in a duel with George Washington’s distant cousin, Colonel William Washington (1752-1810), Tarleton escaped after Washington’s sword broke at the hilt; in the process, he wounded Washington and his horse with a pistol shot.

Tarleton also favoured what would now be called ‘decapitation strikes’. In March 1781, he launched a raid on Charlottesville, Virginia, in the hope of capturing Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), then governor of the state. As a Brigade Major in 1776, he diverted a scouting party under his command to capture Colonel Charles Lee (1732-1782) in a New Jersey tavern. Lee was one of the very few American officers who had ever served the British crown – in the very regiment that captured him! Tarleton may have, inadvertently, done the Americans a favour: Charles Lee was a dour and pessimistic officer and, after an exchange secured his release, he nearly lost the battle of Monmouth in 1778 out of his conviction that the Continentals could never prevail against British soldiers.

Another Lee was the far more capable Henry Lee, Light Horse Harry’ to his peers and his soldiers. Lee made his reputation from his own ability to appreciate and take advantage of an opportunity – a trait for which his considerably more famous son Robert E. (1807-1870) is legend.

In perhaps the strangest use of cavalry during the war, Lee and his Virginian Dragoons were instrumental in feeding the Continental Army during the terrible winter of 1777-78. Washington forbade the confiscation of forage from the friendly Pennsylvania farm country, and his men suffered greatly. An early and heavy run past Valley Forge of small, fatty fish called shad offered hope – more, certainly, than was offered by Washington’s desperate letters to Congress asking for food. Men plunged into the water with nets, buckets, pitchforks, anything to toss the shuddering fish on shore. Seeing that the shoal was about to move past the desperate Continentals, Lee ordered his dragoons to charge into the Schuylkill River. The churning of the horses’ legs in the water frightened the fish back into the nets and the clutches of the starving soldiers. There was even a surplus, which would help in the lean weeks that were to follow.

A String of Outposts

By 1779, the War of Independence had entered nearly its final phase. Washington’s army, including the infant cavalry arm, emerged from Valley Forge with a confidence and level of drill that enabled them to face the regulars of General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-1795) in pitched battle – as they demonstrated despite Charles Lee’s misgivings at Monmouth. Clinton accordingly held his army in the port and city of New York, the most economically and strategically valuable territory in the Colonies, with a chain of outposts to secure communications and movement throughout eastern New York and New Jersey. The British offensive effort in subsequent years would be concentrated in the southern colonies, with ‘Bloody Ban’ Tarleton leading British and Loyalist forces on raids throughout the South until Tarleton’s conclusive defeat at Cowpens in January of 1781.

Defended enclaves can pacify a considerable portion of surrounding territory if they can support each other – as the United States has recently demonstrated in the urban environments of Iraq. The difficulty lies in establishing how far apart such outposts can be placed, in order to maximize the area of territory while still leaving them capable of mutual support and rapid relief in the event of a major attack. In August 1779, Major Lee, then 23 years old, took advantage of the absence of Nathaniel Greene (1742-1786), Washington’s quartermaster at Valley Forge, to approach Washington and express his belief that Clinton had made a major mistake in the positioning of his outposts.

A Penny Packet

The modern site of the battle of Paulus Hook is a street corner in Jersey City, New Jersey. In 1778, it was a peninsula jutting out from the New Jersey shore, directly opposite New York City and the Hudson. That July, Clinton led out a powerful force from the peninsula towards the American bastion of West Point. General ‘Mad Anthony’ Wayne (1745-1796) had earlier captured the British outpost at Stony Point after Clinton retreated back down the Hudson. Lee suggested to Washington that a similar such sudden onset might take an additional bastion directly under Clinton’s nose.

The fort at Paulus Hook was essentially a fortified beachhead on the New Jersey shore, onto which the British could land and from which they could move out to exert their control over the nearer countryside. The fort’s garrison consisted of 200 men of the British 64th Regiment, under Major William Sutherland, plus 200 Loyalists, enclosed within tremendously strong fortifications. Traffic could ford the creek in front of the peninsula at only two points.

As a second line of defence, British engineers had cut a moat across the neck of the isthmus, the only access being through a barred drawbridge gate. In between the drawbridge and the actual stockade itself were the entanglements of the day, abatis – lopped trees felled and cut in a manner calculated to impede or halt an attacker’s movement under the garrison’s fire.

Behind that were three batteries of cannon, commanding the Hudson and the countryside, as well as a central bastion with barracks, plus the fort’s magazine and six cannon. At some distance, there were an additional infantry redoubt and a blockhouse. The British rear lay safe under the guns of the British fleet in the Hudson, and Clinton had established a set of lantern codes and signal guns to summon aid from New York.

Transmitted Intelligence

Lee’s plans for a swift descent upon the fort were fleshed out by a diet of information provided by Captain Allen McLean, commander of a force of mounted rangers. These long-range scouts lurked in the salt-water marshes at the base of the peninsula and transmitted a fairly accurate ongoing report of the numbers and status of the fort’s garrison. Even today, a horse’s ability to traverse swamp, water and road compares favourably with mechanized transport.

An additional example of the efficacy of horses in difficult terrain is provided by the career of the legendary ‘Swamp Fox’ – General Francis Marion (1732-1795). He earned his sobriquet by lurking in the South Carolina swamps. With his troopers using and feeding their own horses in the course of their raids and forays, Marion made British control of the region uncertain even after the disastrous American capitulation at Charleston in May 1780. Eventually Lord Cornwallis (1738-1805) sent Tarleton himself to bring the ‘Swamp Fox’ to bay, but Marion’s intelligence network, and his use of the rivers to move and conceal his cavalry, proved more than Tarleton’s celebrated ferocity could overcome.

Washington approved of Lee’s raid, on certain conditions: there would be no effort to hold the post. Lee was to capture the garrison, disable the cannon, blow up the magazine and retreat to a fleet of pontoon boats in the nearby Hackensack River before the British could counter-attack. Lee accordingly dismounted his own dragoons and used McLean’s mounted rangers to control the roads leading into Paulus Hook. Colonial horsemen would prevent warning of Lee’s attack from reaching the bastion, or any messages for aid from reaching any British detachments on the Jersey shore.

Lee’s choice to put his troopers on foot was a difficult call, but one necessitated by his bargain with Washington. The circular route planned for the attack was a 22.5km (14-mile) march through the marshes into the post, then a shorter rush with the prisoners out to and across the river and safety. Ferrying horses under pursuit was too great a risk for Lee’s own command, and his mounted forces were relegated to screening and reconnaissance duties.

Captain McLean’s surveillance had been quite intensive, but the aftermath of the battle revealed that his scouts and one disguised spy had missed two vital elements in the situation. The first, which would hinder Lee, was the arrival of a force of 40 Hessians sent over from New York to bolster the garrison. The second determined the ultimate success of the onslaught, for on the night of Lee’s attack Major Sutherland sent 132 of the Loyalists in a foraging party out into the Jersey countryside. The British sentries, accordingly, were expecting a large number of men coming stealthily towards their post – friendlies.

Chest-high Water

By 1779, the Americans had captured considerable cavalry equipment from the British, which they used to equip their own units. A great many of the heavy sabres taken from British troopers in 1778 wound up in American hands. The British had provided their own forces with lighter carbines and musketoons, which meant that Lee and his men carried full-size British Brown Besses’ and French Modele 1763 Charleville muskets. Lee divided his force of approximately 400 men into three columns delineated by their origins: a force of McLean’s dismounted rangers, a company of the 16th Virginia and two Maryland companies. The three forces were to arrive simultaneously at the objective by three different routes, an early example of the traditional American preference for columns converging on a single objective. In the event, optimism and synchronicity failed.

The combined force set forth with a wagon train in the early evening of 18 August as a deception aimed at lurking British spies. The hope was that they would mistake the formation for a supply convoy. The three columns divided once they entered a woodland, and the Maryland force and the Virginians got utterly lost in the darkness, reducing Lee’s forces to the 200 men under his own direct command. Long experience of travel had its uses, for Lee’s horsemen continued on towards the distant garrison while avoiding the roads where detection would be the most likely. Instead they waded chest-high through creeks and canals until they reached the British moat, their cartridge belts and muskets utterly soaked. The time was now 3 a. m.

Lee broke his remaining men into a vanguard and reserve, and ordered his men to fix bayonets and ford the British ditch at a shallow spot located by one of his lieutenants. The initial force struggled through the water, up the slope, and into the abatis, through which they pried their way with their bayonets. As the British sentries began to realize that this was not their foraging party and began to fire, Lee’s reserve column rushed up through the area cleared by the vanguard and carried the gate into the fortification with a bayonet charge. About 12 of the British were killed before the bulk of the garrison surrendered.

Success and Withdrawal

Major Sutherland and 26 of the Hessians managed to barricade themselves into the smaller of the two infantry redoubts. From there, they peppered the Americans with largely inaccurate fire and sent alarm signals to the British in New York. These were answered by ships in the Hudson and cannon from Manhattan, and Lee knew that his time was running out. Lee found his men surrounding 156 surrendered British soldiers and three officers. Darkness, confusion and the need for haste kept Lee from disabling the post’s cannon, a procedure usually performed by thrusting a bayonet into the gun’s touch-hole, rendering the cannon briefly or permanently unable to fire.

Humanity frustrated two more of Lee’s objectives. As his men moved to burn the British barracks and fire the fort’s magazine, they found the families of some of the garrison and sick men cowering inside the buildings. Lee accordingly rounded up his captives and made for the main road out of the post, only to find that his plans continued to go relentlessly astray. Lee availed himself of a horse and rode ahead to the appointed rendezvous with the boats on the Hackensack. No boats waited there, the commander having assumed as the sun rose that the attack had been cancelled. Lee rode back to his men and their prisoners on the road, finding 50 of the missing Virginians on the way, their cartridges still dry.

Lee had no choice, accordingly, but to retrace the original route of the attack. This was exposed in the daylight to British observation and interdiction, potentially trapping Lee’s force: the Loyalists were returning from their foraging expedition and the Hessians and Major Sutherland were pursuing from the fort, while reinforcements were already on their way across the Hudson. The Loyalists, under the hated Colonel Van Buskirk, met the column at the ferry road and opened fire, drawing a return volley from the Virginians and from the 200 reinforcements providentially sent to Lee by the American commander in New Jersey, General William Alexander (1723-1786). Lee’s prisoners could march, and his own casualties were extremely light: two killed, three wounded.

McLean’s horsemen had done their work well in restricting information of the raid. (The descendants of one little girl would later record her memories of being detained by the rangers screening Lee’s movements as the assault force passed.) Coming down the road from the fort, Major Sutherland ran into Lee’s reinforced rearguard and retreated back to his empty bastion, concluding the raid in the Americans’ favour. The fort at Paulus Hook would be re-garrisoned and held until the final British retreat from North America, but from now on it was a beleaguered liability, not a useful foothold. ‘Light Horse Harry’ would receive a medal from the Continental Congress and further opportunities for daring exploits in the successful War of Independence.