The capture of Philippsburg and Mainz had given France secure access over the Rhine, but the Lower Palatinate was too devastated to provide an adequate base for them inside Germany. The local truce ruled out use of the Franche-Comté to the south, heightening the importance of securing Swabian territory east of the Black Forest to sustain French forces in the Empire. News of Jankau emboldened Mazarin to believe there was a real chance of knocking Bavaria out of the war and Turenne was ordered to achieve this.

Both sides spent the opening months of 1645 raiding each other across the Black Forest. Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, Viscount of Turenne was delayed by the need to rebuild his infantry shattered at Freiburg, while Franz von Mercy had detached Johann von Werth and most of the cavalry to Bohemia. Only 1,500 troopers returned in April. Turenne was able to attack first, crossing the Rhine with 11,000 men near Speyer on 26 March and advancing up the Neckar into Württemberg, which he thoroughly plundered. He then moved north-east, taking Rothenburg on the Tauber to open the way into Franconia. Mercy deliberately feigned defeatism, keeping to the south while he collected his forces. Turenne remained cautious, but was unable to sustain even his relatively small army in the Tauber valley. He moved to Mergentheim, billeting his cavalry in the surrounding villages in April.

Having received Maximilian’s permission to risk battle, Mercy planned to repeat his success at Tuttlingen. Werth’s arrival gave him 9,650 men and 9 guns at Feuchtwangen. He force-marched his troops 60km to approach Mergentheim from the south-east on 5 May. Turenne had been alerted by one of Rosen’s patrols at 2 a.m., but there was little time to collect his troops at Herbsthausen, just south-east of the town. He knew he could not trust his largely untried infantry in the open, so posted them along the edge of a wood on a rise overlooking the main road. Most of the cavalry were massed to the left ready to charge the Bavarians as they emerged from a large wood to the south. He had only 3,000 troopers and a similar number of infantry, though not all were present at the start of the battle and another 3,000 billeted in the surrounding area never made it at all.

Werth appeared first at the head of half the Bavarian cavalry to cover the deployment of the rest of the army on the other side of the narrow valley opposite the French. Mercy used his artillery to pound the wood, increasing the casualties as the shot sent branches flying through the air, just as the Swedes had done to the Bavarians at Wolfenbüttel. None of the six French cannon had arrived. Their infantry fired an ineffective salvo at long range and fell back as the Bavarians began a general advance. Turenne charged down the valley, routing the Bavarian cavalry on the left that included the units beaten at Jankau. However, a regiment held in reserve stemmed the attack, while the few French cavalry posted on Turenne’s extreme right were swept away by Werth’s charge. The French army dissolved in panic, many of the infantry being trapped around Herbsthausen. Turenne cut his way through almost alone to join three fresh cavalry regiments that arrived just in time to cover the retreat. The subsequent surrender of Mergentheim and other garrisons brought the total French losses up to 4,400, compared to 600 Bavarians.

The success was not on the scale of Tuttlingen, but it was sufficient to lift the despondency in Munich and Vienna after Jankau. The sequence of these actions underscores the general point about the interrelationship between war and diplomacy, as each change of military fortune raised the hopes in one party of achieving their diplomatic objectives, while hardening the determination of the other to continue resisting until the situation improved. In this case, Mercy was too weak to exploit his victory beyond securing the area south of the Main. Mazarin moved swiftly to restore French prestige before negotiations moved further in Westphalia. Louis II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, D’Enghien was directed to take another 7,000 reinforcements across the Rhine at Speyer, and in a new show of common resolve Sweden agreed to despatch Königsmarck from Bremen to join the French. Having reinforced the garrisons in Meissen and Leipzig, Königsmarck arrived on the Main with 4,000 men. The return of the war to the Main area allowed Amalie Elisabeth to revive Hessian plans to attack Darmstadt under cover of the general war. She agreed to provide 6,000 men under their new commander, Geyso, who assembled at Hanau to invade Darmstadt in June.

The Battle of Allerheim [Battle of Nördlingen (1645)]

Ferdinand of Cologne sent Gottfried Huyn von Geleen and 4,500 Westphalians south past the allies to join Mercy on 4 July, to give him about 16,000 men against the enemy’s 23,000. Mercy then retired south to Heilbronn, blocking the way into Swabia. The allied troop concentration soon broke up. One commonly cited reason was that d’Enghien had managed to insult both Johann von Geyso and Hans Christoff von Königsmarck. However, the real cause of the latter’s departure in mid-July was an order from Lennart Torstensson to knock out Saxony. The instructions, dated 10 May (Old Style), were later copied and sent to Johann Georg to put pressure on him to negotiate. Given Torstensson’s inability to take Brünn, there was only a limited period of time in which to intimidate Saxony before the Imperialists recovered sufficiently to send assistance. D’Enghien meanwhile resumed Turenne’s earlier plan and marched east through southern Franconia heading for Bavaria. The division of military labour evolving since 1642 was now complete. Sweden would eliminate Saxony and attack the emperor while France knocked Bavaria out of the war.

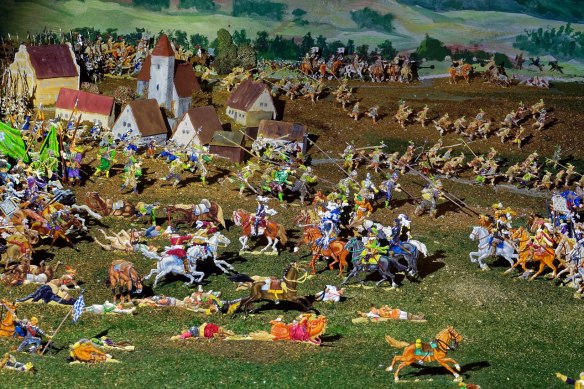

Mercy deftly checked the French advance by taking up a series of near impregnable positions, obliging d’Enghien to waste time outflanking him. The game ended at Allerheim near the confluence of the Wörnitz and Eger rivers on 3 August. Though it is also known as the second battle of Nördlingen, the action was fought on the opposite side of the Eger to the events of 1634. Mercy had deployed with his back to the Wörnitz between two steep hills on which he entrenched some of his 28 cannon. The infantry, who comprised less than half his army, were positioned behind Allerheim in the centre. The cemetery, the church and a few solid houses were filled with musketeers, while others held entrenchments around the front and sides of the village. The cavalry were massed either side, with Geleen and the Imperialists on the right (north) as far as the Wenneberg, and Werth with the Bavarians on the left next to the Schloßberg hill, named after the ruined castle on the top.

D’Enghien had not expected to find the enemy, but seized the opportunity for battle despite his subordinates’ reservations. Königsmarck’s departure had left him with 6,000 French troops, plus 5,000 more under Turenne and the 6,000 Hessians, with 27 guns. He placed most of the French infantry and 800 cavalry in the centre opposite Allerheim, while Turenne stood on the left with the Hessians and his own cavalry. The rest of the French were deployed on the right (south) under Antoine III de Gramont opposite the Schloßberg.

It was already 4 p.m. by the time they were ready, but d’Enghien knew from Freiburg how quickly the Bavarians could dig in and did not want to give them the night to complete their works. The French guns could not compete with the Bavarians’ that were protected by earthworks, so d’Enghien ordered a frontal assault at 5 p.m. He was soon fully occupied with the fight for Allerheim, leading successive waves of infantry over the entrenchments, only to be hurled back again by fresh Bavarian units fed by Mercy from the centre. The thatched roofs of the village soon caught fire, forcing the defenders into the stone buildings. The French commander had two horses shot under him and was himself saved by his breastplate deflecting a musket ball. Mercy was not so fortunate as he entered the burning village around 6 p.m. to rally the flagging defence. He was shot in the head and died instantly. Johann von Ruischenberg assumed command and repulsed the French.

Werth meanwhile routed Gramont who thought a ditch in front of his position was impassable and allowed the Bavarians to approach within 100 metres. The French cavalry offered brief resistance before fleeing, leaving Gramont to fight on with two infantry brigades until he was forced to surrender. Werth’s cavalry dispersed in pursuit and it is possible that the smoke from Allerheim obscured the battlefield. Either way, he discovered that the rest of the army was on the point of collapse only when he returned to his start position around 8 p.m. Turenne had saved the day for the French with a desperate assault on the Wenneberg that allowed the Hessians, the last fresh troops, to overrun the Bavarian artillery and hit Allerheim in the flank. Parties of Bavarian infantry were cut off in the confusion and surrendered. Werth assumed command, collected the army at the Schloßberg and retreated around 1 a.m. in good order to the Schellenberg hill above Donauwörth.

Werth attracted considerable blame, especially from later commentators like Napoleon, for failing to exploit his initial success by sweeping round behind the French centre to smash Turenne as d’Enghien had done with the Spanish at Rocroi. Werth defended himself by pointing out the difficulties of communicating along the length of the Bavarian army that probably measured 2,500 metres. His troopers were also short of ammunition and it was getting dark by the time they reassembled. Indeed, the late hour probably proved decisive, limiting what Werth could see. His withdrawal was prudent under the circumstances, depriving the Bavarians of a chance for victory, but at least avoiding a worse defeat that would have wrecked the army.

D’Enghien had been fortunate to escape with victory, losing at least 4,000 dead and wounded. The infantry in the centre had been almost wiped out and the French court was aghast at the extent of casualties that included several senior officers. Like Freiburg, it was the Bavarian retreat that transformed the action into a strategic success, partly because at least 1,500 men were captured as Werth pulled out of Allerheim in addition to the 2,500 killed or wounded. Retreat after another hard-fought battle eroded morale. The Bavarians vented their fury on the unfortunate captive Gramont, who narrowly escaped being murdered by Mercy’s servant and was grateful to be exchanged for Geleen the next month.

The Kötzschenbroda Armistice

The immediate repercussions were soon redressed. The French captured Nördlingen and Dinkelsbühl, but got stuck at Heilbronn where d’Enghien fell ill. Mazarin refused to send reinforcements to replace the casualties, leaving Turenne outnumbered as Leopold Wilhelm and 5,300 Imperialists arrived from Bohemia in early October. By December, Turenne was back in Alsace having lost all the towns captured that year.

The stabilization of southern Germany was offset by a major blow in the north-east that indicated that the new allied strategy was working. Though the French had been unable to knock out Bavaria, their campaign in Franconia prevented relief reaching Saxony, which had been left isolated after Jankau. Königsmarck had force-marched the Swedish forces up the Main and burst into the electorate early in August. Johann Georg appealed to Ferdinand, protesting that the Swedes were deliberately ravaging his land. The emperor replied on 25 August that he had just made peace with Georg I. Rákóczi and help was on its way. It was too late. Before the letter arrived, the elector had already given up hope; he concluded an armistice at Kötzschenbroda on 6 September.

Saxony secured a six-month ceasefire on relatively favourable terms. The Swedes accepted the electorate’s neutrality, but allowed it to continue discharging its obligations to the emperor by leaving three cavalry regiments with the imperial army. In return, Saxony had to pay 11,000 talers a month to maintain the Swedish garrison in Leipzig, the only town Königsmarck insisted on retaining in the electorate. The Swedes were allowed to cross the electorate, but they also agreed to lift their blockade of the Saxon garrison in Magdeburg.