By late December 1810 Marshal Jacques Macdonald had stabilised the situation in the north of Spain and was again able to support Louis-Gabriel Suchet’s attempts to capture Tortosa. Suchet therefore moved to begin the siege on 16 December, and for once the Spanish failed to defend a strong fortress well. In fact, by 2 January 1811 the place was entirely in French hands.

This success immediately released Macdonald to carry out the siege of Lerida, whilst Napoleon ordered Suchet to take Tarragona, arbitrarily transferring half of Macdonald’s corps to Suchet’s command. At this, Macdonald promptly retired to Barcelona and left Suchet to it.

On 9 April 1811 the French were shocked to hear that the fortress of Figueras had again fallen into Spanish hands, once more threatening the supply route from France. The local Spanish insurgents had worked with a few patriots within the fortress to obtain copies of the keys to the gates and surprised the garrison before any resistance could even be attempted.

Macdonald sent the news to Suchet, asking him to abandon all thoughts of besieging Tarragona and instead to march north with his entire army. Suchet rightly pointed out that it would take him a month to march northwards, and suggested that Macdonald should seek help from France instead, given that the French border lay only 20 miles from Figueras. Suchet then began his march to Tarragona on 28 April, believing that this operation would draw the Spanish south in an attempt to relieve the place.

Napoleon promptly scraped together a force of 14,000 men at Perpignan, whilst General Baraguay d’Hilliers, commanding at Gerona, managed to collect another 6,000 men. Between them, this force of 20,000 men would seek to recapture Figueras, a task made much easier when the Spanish General Campoverde reacted exactly as Suchet had predicted and moved his force of 4,000 men by sea to help save Tarragona. He abandoned the 2,000 men of the garrison of Figueras to their fate and Marshal Macdonald then moved north to take personal command of the siege of Figueras.

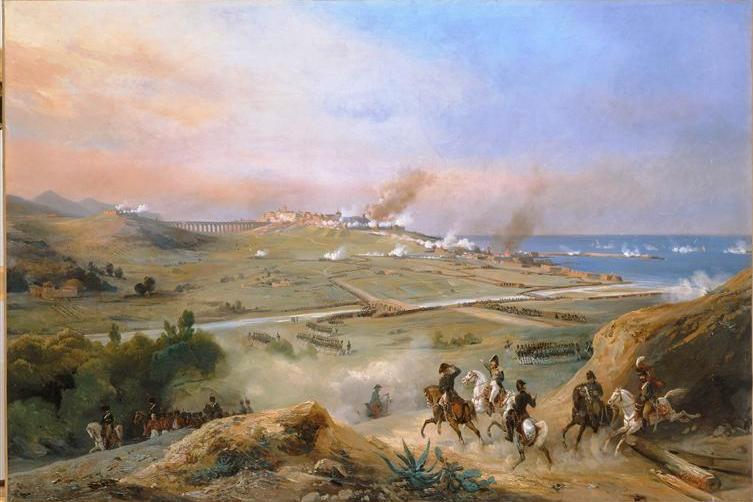

Suchet began the siege of Tarragona on 7 May and three days later General Campoverde arrived by sea and bolstered the defenders with his 4,000 troops. The French were obliged to work very close to the coastline, which rendered their works vulnerable to fire from British and Spanish ships. To remedy this, the first batteries constructed faced the sea and their guns forced the warships to move further away. The French now concentrated their efforts on capturing Fort Olivo, a detached redoubt protecting the lower town. This was successfully stormed on the 29th.

Two further battalions of Spanish troops arrived by sea from Valencia, but General Campoverde sailed to seek further support, leaving General Juan Contreras in command. By 17 June the French had captured all the external defences of Tarragona and the siege was reaching a critical point; Contreras, despite having 11,000 men, simply failed to disrupt the French besiegers at all. On the 21st the lower town was successfully stormed, meaning that command of the harbour also fell to the French. Things now looked bleak for Contreras, particularly with Campoverde accusing him of cowardice from a safe distance away.

On 26 June, however, things improved for the Spanish commander. A number of troop ships arrived with a few hundred Spanish troops on board; better still, some 1,200 British troops1 commanded by Colonel John Skerrett also arrived, having been sent by General Graham at Cadiz to aid the defence. Skerrett landed that evening and surveyed the defences with the Spanish; it was unanimously agreed that Tarragona was no longer tenable. As Graham had specifically ordered that the British troops were not to land unless Skerrett could guarantee that they could safely re-embark, he rightly decided to abandon the attempt and sailed with the intention of landing further along the coast and subsequently joining with Campoverde’s force. But this was a depressing sight for the Spanish defenders and undoubtedly damaged their already fragile morale. In fact, the very day that breaching batteries opened fire on the walls, a viable breach was formed by the afternoon and was promptly stormed. Within half an hour all the defences had given way and the French infantry swarmed into the town. A terrible orgy of rape and murder followed, and it is estimated that over 4,000 Spaniards lost their lives that night, over half of them civilian. At least 2,000 of the Spanish regulars defending the town had been killed during the siege and now some 8,000 more were captured.

The capture of Tarragona earned Suchet his marshal’s baton; it had destroyed the Spanish Army of Catalonia and severely hampered British naval operations along the coast. By contrast, Campoverde was soon replaced by General Lacy, who took the few remaining men into the hills to regroup.

Suchet marched northwards to Barcelona, ensuring that his lines of communication were secure. On discovering that Macdonald was progressing well with his siege at Figueras, he turned his attentions to capturing the sacred mountain stronghold of Montserrat, which fell on 25 July. The damage to Spanish morale proved more important than the physical retention of this monastic stronghold. On 19 August Figueras was finally starved into submission after a four-month siege, thus re-opening the French supply routes. Napoleon was delighted by the news but he promptly reminded Suchet that he was yet to capture Valencia.

The Spanish forces under General Lacy continued to make forays, even into France, and attempted to disrupt French communications with predatory raids by both land and sea. These operations restored somewhat the shattered morale of the Spanish guerrillas and the flame of insurrection, so nearly snuffed out, continued to flicker and occasionally flare up, giving the Spanish some hope. Macdonald was recalled to France, another Marshal of France finding eastern Spain a step too far.

Despite his own strong misgivings, Marshal Suchet again marched south for Valencia with a force of some 22,000 men. General Joaquin Blake, commanding some 30,000 men, was tasked with opposing him but simply allowed him to march there without resistance. Suchet’s force arrived at Murviedro on 23 September and, having signally failed in a foolish attempt to storm the fortress of Saguntum by direct escalade, the French army sat down before it and patiently awaited the arrival of the siege artillery, only opening fire on 17 October. Suchet attempted a second costly assault without success and looked nervously over his shoulder at the insurrections breaking out in his rear. However, at this point General Blake decided that he must advance to protect Saguntum; having collected no fewer than 40,000 men, he attacked Suchet on 25 October and was soundly beaten for his troubles, losing over 5,000 men. The garrison of Saguntum, acknowledging that there was now no hope, surrendered the following day. Blake had simply given Suchet’s troops hope, when in fact they had none.

Suchet now continued his march on towards Valencia. Arriving on the north bank of the Guadalquivir river, he found Blake facing him again, encamped on the southern bank with some 30,000 men. Having only 15,000 men with him, Suchet formed an encampment here and awaited reinforcements, with which he could advance to prosecute the siege of Valencia.

Napoleon, badly underestimating the British army under Wellington, but simultaneously recognising the importance of capturing Valencia, ordered King Joseph’s army to further supplement Suchet’s operations. Marshal Marmont’s army, facing Wellington, was also weakened when Napoleon ordered him to send Suchet 12,000 men. These developments would have a very significant effect on Wellington’s operations a few months later, in early 1812.

The promised reinforcements arrived with Suchet in late December and he immediately advanced to prosecute the siege of Valencia on the 26th, successfully completing the investment of the city by that evening. By 1 January work had begun on preparing siege batteries, which were armed and ready to proceed by the 4th.

Blake moved his troops from his fortified camp in the hills into the city, but the prospects for a successful defence appeared to be very poor. There was already a severe shortage of food and the morale of the Spanish troops was so low that they were deserting en masse. Suchet added significantly to their discomfort by bombarding the city with shells until the morale of the defenders finally collapsed. Blake was forced to agree to surrender on 9 January, with around 16,000 Spanish soldiers laying down their arms.

The almost impregnable fortress of Penissicola, garrisoned by some 1,000 Spanish veterans, was now besieged, the siege guns beginning a heavy bombardment on 28 January. Despite being well supplied with food and stores by the British navy, and his troops proclaiming their determination to fight on, General Garcia Navarro, the fortress commander, seems to have lost all hope after Valencia fell. A letter describing his fears was captured by the French and used to exert enormous pressure on a man obviously unable to cope; when a forceful summons was sent in on 2 February, the commandant surrendered without delay. Almost the entire east coast of Spain was now in French hands.