Cruisers evolved from the frigates of the nineteenth century and were broadly defined as ships capable of independent operations on distant stations, able to fight any opponent other than a capital ship, and adaptable to a wide variety of tasks. They had the fuel stowage and workshops to enable them to undertake long periods without support from depot ships or bases. After 1890 cruisers were reclassified according to a system in which First Class ships had 9.2-inch guns and were capable of acting as a fast squadron of the battle fleet, although not of engaging battleships independently. Second Class ships had 6-inch guns; Third Class ships had lesser guns and were not expected to work with the fleet. They were spread throughout the British Empire to protect trade and British interests. All sailors were given military training and, as well as landing Royal Marines, cruisers were expected to be able to land a company of ‘bluejackets’, usually stokers, for operations on land when required. Some of the lighter ship’s guns were designed to be dismounted and fitted on wheeled carriages for operations ashore, the origin of the Field Gun Competition which is still familiar in military tournaments. The ability of cruisers to spread their influence from the sea onto the land in this manner may have given the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the germ of the idea to form a Royal Naval Division for operations on land in 1914.

By 1905 the large, protected cruisers of the old first class were reduced to reserve, their role being taken over in the next decade by battlecruisers. Ships that survived after 1914 were used for subsidiary duties, dispersed to remote stations where they were unlikely to see action, or expended as block-ships. Admiral Fisher had originally no intention of including cruisers in his modernised fleet but experience showed that battlecruisers on their own were too expensive to provide a large fleet with all the reconnaissance it needed and, at the other end of the spectrum, as a cruiser-substitute the large destroyer Swift proved to be a disappointment in service. In response, a series of fast, light cruisers were built, starting with the Bristol class of five ships completed in 1910. In 1911 the old system of classification was discontinued, the larger armoured ships becoming known simply as cruisers, and the new ships, all of which were named after cities and towns, as light cruisers. Steady evolution of the design brought a series of classes after Bristol, including the Weymouth, Chatham and Birmingham classes. Three ships of the Chatham class were built for the Royal Australian Navy, two of which, Melbourne and Sydney, served with the Grand Fleet. By 1918 town names were replaced by classes of ships with names which began with the same letter of the alphabet; first the ‘C’s and then the ‘D’s and further construction evolved through the Caroline, Cambrian and Centaur classes. Light cruisers bore the brunt of fighting in the North Sea, and many continued in service after 1919.

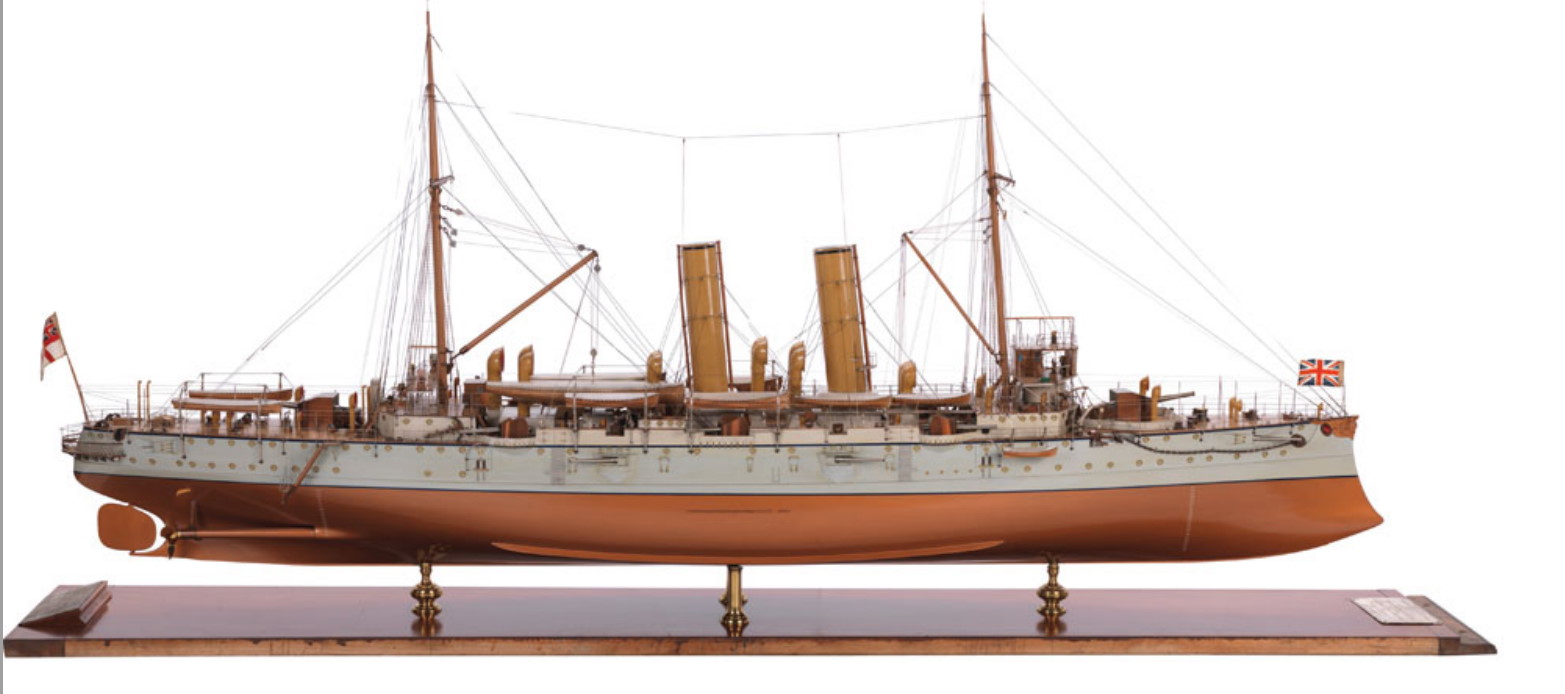

Gibraltar was laid down in 1889 and this highly detailed 1/48 scale model was made by her builder, William Beardmore of Dalmuir on the Clyde. She was one of nine First Class protected cruisers of the Edgar class; well-liked ships with an armament of two 9.2-inch and ten 6-inch guns. She had triple-expansion steam engines driving two shafts and four double-ended, coal-fired boilers. Top speed was 19 knots and the whole class had a reputation for being mechanically reliable in service. One of Gibraltar’s sister-ships steamed at 18 knots – effectively full speed – for 48 hours. She had four submerged 18-inch torpedo tubes with a number of reloads and a 5-inch armoured deck.

Like all builder’s models, this one shows considerable detail. The single 9.2-inch guns are visible fore and aft with the 6-inch guns distributed around the central superstructure. Boats are stowed inboard and on davits with derricks rigged to work the former; all fittings are gold- and silver-plated so that they stand out against their backgrounds. The large number of ventilators visible around the funnels were there to draw air into the boilers. The hull below the real ship’s waterline was sheathed in copper as an antifouling measure and this is accurately represented on the model.

Like her sister-ships, Gibraltar spent her early life deployed outside the UK, in the Mediterranean, South Atlantic and the America and West Indies Stations between 1894 and 1906. Reduced to a nucleus ship’s company in Devonport, she was brought forward to escort the new destroyers Parramatta and Yarra to Australia in 1910/11. By 1914 she was in use as a depot ship for the anti-submarine school at Portland but on the outbreak of war she joined the 10th Cruiser Squadron which formed the Northern Patrol, guarding the northern entrances to the North Sea to prevent German shipping from evading the British blockade. When armed merchant cruisers more suited to the task became available in 1915, she was disarmed and used as a depot ship for the Northern Patrol, based in the Shetland Islands until 1918. In 1919 she returned to the anti-submarine school as a depot ship until 1922 when she was withdrawn from service and scrapped.

ARMOURED CRUISERS

Earlier RN cruisers had relied on a protective armoured deck for defence against shellfire (and hence were usually classified as ‘protected cruisers’), but the advent of face-hardened steel armour in the mid-1890s allowed a comparatively large area of the hull sides to be armoured as well; the new ships with this form of protection were known as armoured cruisers. The first of these were the six 12,000-ton Cressy class ordered in 1898.

By the outbreak of war in August 1914 they were obsolescent, but five of class formed the 7th Cruiser Squadron. The following month three of them, the Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue, were being used to patrol an area of the southern North Sea known as the ‘Broad Fourteens’ off the Dutch coast. They were intended to provide distant cover for the movement of troops to France but were themselves exposed by the lack of immediate cover by capital ships, and rough weather in the previous days had prevented them from having any destroyer escort. By dawn on 22 September the weather had abated and the ships were cruising slowly in company without taking any evasive measures. At 0630 Aboukir was hit by a torpedo from U 9 and began to sink. Thinking that she had struck a mine, Hogue closed her to pick up survivors and was, in turn, torpedoed by U 9. Seeing both her sister-ships sinking, Cressy stopped among the survivors. By then U 9 had surfaced and Cressy opened fire on her before she, too, was torpedoed and sunk. Between them, the three cruisers lost 1449 men; among them were many from an entire term of Dartmouth cadets that had been embarked to gain sea experience. This incident taught the Royal Navy hard lessons about the new technology and tactics required in naval warfare.

This finely-detailed waterline model from the Imperial War Museum’s collection depicts Cressy, the name ship of a class of six armoured cruisers. She was built by Fairfield at Govan and completed in 1901. The design was based on the earlier Diadem class protected cruisers, but with two single 9.2-inch guns replacing four of the earlier ship’s sixteen 6-inch guns. Her forward and after secondary 6-inch guns were mounted in the same unsatisfactory double-tiered casemates, with the lower guns difficult, if not impossible, to use in rough seas. The guns mounted between them, although not double-tiered were also too close to the waterline. This 1/192 scale model was made by Julian Glossop and shows the ship as she appeared in 1914. Rigging and boats are well formed with larger boats stowed on deck aft of the after funnel below the derrick used to launch them. Two boats are suspended from davits and the forward one is a sea-boat with white painted gripes holding it firmly in place. The forward boat boom can be seen in its stowed position just aft of the forward, lower 6-inch casemate.

The Drake class was a logical development of the earlier Cressy class armoured cruisers with improved machinery making them among the world’s fastest major warships at the time of their completion (some exceeded their design speed of 23 knots on trials). Referred to by Lord Goschen, the First Lord of the Admiralty, as ‘mighty cruisers’, they were also unusual for their time in being able to steam for long distances at high speed. In terms of armament they showed less progress, however, with their secondary 6-inch guns mounted one above the other in four double casemates on each side of the hull. The lower guns were close to the waterline and proved to be impossible to work in rough weather. They had an armoured belt along the side of the hull which was 6 inches at its thickest point, tapering to 3 inches at either end with a full armoured deck 3 inches thick at the centre, tapering to 1 inch at the bow and stern. As a type, however, they were soon rendered obsolescent by battlecruisers.

Leviathan was one of the four ships of the Drake class that formed part of the 1898 Construction Programme and this 1/48 model was made by her builder, John Brown of Clydebank. It is exceptionally well detailed and many of its finer points are beautiful little models in their own right. It shows her as she appeared when completed in 1903, shortly before the Royal Navy adopted a grey paint scheme for ships on the Home Station.

Leviathan: the lower 6-inch guns in their double casements stand out clearly, as does the fully-detailed rigging. Anchors, cables, boats and the bridge are all finely detailed. The bridge wings were intended both to give the captain a good view over the side when coming alongside in harbour and space for signalmen to work at flag-hoists, semaphore and the use of the signal lamps at the outer edge while at sea. The enclosed bridge contains a ship’s wheel and compass binnacle, features that are replicated in the secondary conning position aft of the main mast. The three after funnels are lozenge-shaped and the forward one is circular, indicating the differing number of boilers connected to it. Seventeen boats are stowed on deck or suspended from davits; three of the boats stowed aft of the funnels are steam pinnaces, each capable of being armed with quick-firing guns and torpedoes in their own right to attack enemy vessels in harbour. Mechanical semaphore arms are located in the bridge wing and at the top of the main mast; other details include hose reels, winches and a number of small guns. The whole class, including Leviathan, were intended to be used as cruiser squadron flagships on distant stations and they all had a stern walk right aft, opening out of the admiral’s harbour accommodation.

Leviathan was laid down in 1899 and completed on 3 July 1901. She spent her early years on the Home, Channel, Mediterranean and America and West Indies Stations before becoming the flagship of the Training Squadron in UK waters during 1912. In 1913 she was reduced to a lower degree of readiness and formed part of the 6th Cruiser Squadron in the Third, or Reserve, Fleet. In 1914 she was brought out of reserve with other ships of the 6th, but in December she transferred to the 5th Cruiser squadron which formed part of the Grand Fleet. Her gunnery systems were no longer up to the standard required by the principal fleet, however, and in 1915 she became the flagship of the America and West Indies Station where she looked impressive without too much risk of having to fight a superior opponent. In 1918 she joined other ships in escorting Atlantic convoys and in 1919 she was replaced as the flagship on station and returned to the UK where she was paid off and sold for scrap in 1920.

Leviathan’s amidships area showing the wealth of deck detail in this model, especially the boats. Note the stepping rungs on the side of the hull between the casemates to give access from boats alongside; they are very similar to those in Victory built over a century earlier. A number of quick-firing 3-pounders and Maxim machine-guns are fitted on the upper deck to give a ‘last ditch’ defence against small torpedo-craft at close range.

Midship detail showing steam pinnaces stowed to port and cutters to starboard. A whaler is turned inboard on davits and rope falls are stowed realistically on drums, ready for use. Note the derrick attached to the main mast which was used to lower boats into the water and recover them. It was hand operated with seamen pulling on ropes. The white hatches amidships were opened at sea to provide light and ventilation to the engine rooms below. Note also the after, or secondary, compass platform and wheelhouse with wings similar to the primary position forward. The cruciform shape stowed on the wing extremity is a ‘fog-buoy’ towed astern to create a splash at a safe distance on which other ships could keep station in fog.

The secondary or after bridge, with 3-pounders and Maxim machine-guns mounted behind the screen ahead of the after 9.2-inch turret, which has sighting hoods for the layer, trainer and turret captain. The after bridge duplicated much of the equipment on the main bridge, including the semaphore arm and signal lanterns on the bridge wings, the compass platform with its binnacle over the secondary steering position; there is an engine telegraph and revolution telegraph by the wheelhouse. The wheels for the ship’s landing guns are stowed under the bridge wings.

Detail of Leviathan’s main top showing the small aft-facing signal lantern.

Bow detail showing the ram which was thought to be of value as a weapon in the late nineteenth century but of little value at the ranges ships fought at in the First World War. Note the ‘bow-chaser’ 12-pounder guns in their embrasures and the way anchors were stowed before the introduction of stockless anchors in the early twentieth century. Two anchors were fitted on this side (only one to port) and the blanked off apertures led down to the cable locker. If left open at sea, they could allow water to flood the cable locker, which was one good reason for the subsequent adoption of cable led up onto the forecastle from below leading across hardened plates known as ‘Scotchmen’ to stockless anchors in hawsepipes.

Leviathan’s compass platform and wheelhouse seen from the port side. Note the Maxim machine-gun and semaphore arm near the signal lantern and the superbly detailed deck fittings. Note the circular, armoured conning tower below the wheelhouse from which the ship could be fought in action.

The fore funnel showing its bracing wires and the brass sirens with their steam supply pipes fitted to the small platform half way up. The boats suspended from davits, drums of rope and lockers on the upper deck are all beautiful models in their own right.

SCOUT CRUISERS

After 1900, as torpedo boat destroyers developed realistic sea-keeping qualities that enabled them to operate in the open ocean, a new type of cruiser evolved that was intended to locate and shadow the enemy fleet, command and control destroyer flotillas, lead torpedo attacks and back up destroyers with gunfire when they were required to repel an attack by the enemy’s flotillas. Four classes, each of two ships, were built in quick succession from 1904 onwards, comprising vessels that proved to be an evolutionary step between the earlier Third Class cruisers and the subsequent generation of light cruisers. They were known, initially, as scout cruisers. All eight ships were built to broad Admiralty specifications by firms with experience of destroyer construction, but there were significant differences between them.

Forward was built by Fairfield at Govan, laid down on 22 October 1903 and completed in August 1905, and this 1/48 scale full hull model was made by her builder to show the ship in accurate detail as she appeared when she left the yard. She was 379 feet long with a displacement of 2860 tons and she was powered by two-shaft, three-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines with twelve Thornycroft boilers delivering 16,500 horsepower, which gave her a top speed of 25 knots. The boilers were coal-fired and her bunkers had capacity for 500 tons, giving only a limited radius of action, but at the time the destroyers she was intended to lead were not expected to operate far from their bases. She was lightly armoured with a half-inch deck and 2-inch belt abreast the machinery and her armament reflected the requirement to bring a great deal of rapid fire to bear on the enemy in a high-speed, close-quarter melee. For this reason she was initially armed with ten 12-pounder, unshielded, quick-firing guns. She was not intended to fight enemy cruisers but the two 18-inch torpedo tubes on the upper deck aft of the after funnel gave her the ability to engage larger warships or take part in her flotilla’s attacks. The three forward guns are fitted ahead of the bridge, three are on the raised poop, and the others are mounted along the sides of the deck further aft. Boats are rigged to davits and the open bridge has a covered chart table and other navigational equipment. The single pole mast has a high gaff fitted to it from which wireless telegraphy aerials were rigged.

Forward spent her first two years after completion with a nucleus ship’s company in reserve at Portsmouth before becoming leader of the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla in the Home Fleet in 1909. In 1910 she was attached to the 4th Destroyer Flotilla at Portsmouth and re-armed with nine 4-inch guns, bringing her into line with the new light cruisers. She was also fitted with a single 3-inch anti-aircraft gun. Later in 1910 she joined the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla at the Nore until the outbreak of war when she joined the 9th Destroyer Flotilla which formed the Shetland Island Patrol. During 1915 she served in the Humber but was considered too slow for work with light cruisers or destroyers on operations in the North Sea and she moved to the Mediterranean Fleet where she remained on escort duties until 1918 when she returned to the Nore to pay off. She was sold for scrap in 1921.

LIGHT CRUISERS

By 1909 the older, small cruisers and the newer scout cruisers had evolved into the light cruiser, one of the most prominent warship types used in the First World War. This was a return to traditional cruiser requirements, in between the extremes of armoured cruisers (in effect second class battleships) and the ‘scouts’, which were little more than destroyer leaders. Designed to combine speed, protection, firepower and sea-keeping, the new cruisers were built in four incrementally improved groups, all named after towns. The third group was the Chatham class, three ships of which were built for the Royal Navy and a further three for the Royal Australian Navy. One of the latter was HMAS Sydney, superbly represented by this model in the Australian National Maritime Museum.

At 1/100 scale, the model is finely detailed and accurately depicts Sydney as she appeared in service. Displacing 6000 tons deep load, she was armed with eight 6-inch guns in open shields and two submerged 21-inch torpedo tubes on the beam. The guns were disposed with one on the centreline on the forecastle, one on either side of the bridge; one on either side of the third funnel; one on either side at the break of the quarterdeck and one on the centreline of the quarterdeck further aft. With this arrangement only five guns could be fired on either beam and only three directly ahead or astern. She has been fitted with a spotting top on the tripod fore mast, on the roof of which is a director that controlled the fire of all the guns. She has not yet been fitted with the rotatable aircraft-launching platform added forward of the bridge in 1918, however. The absence of scuttles low on the port side amidships shows where the 2-inch armour belt was fitted to the ship’s side and she had a full armoured deck which was 1.5 inches thick over the machinery, tapering to 0.5 of an inch forward and aft. Sydney had four-shaft machinery with Parsons turbines and twelve Yarrow boilers developing 25,000 shaft horsepower, giving her a speed of slightly over 25 knots. The deck is covered with realistic looking wood planking.

Sydney was built by the London and Glasgow Shipbuilding Company at Govan and completed in June 1913. Together with the battlecruiser Australia and her sister-ship Melbourne, she formed part of the first entry of the Royal Australian Navy fleet unit into Sydney harbour in October 1913. She served in the Pacific in 1914, sinking the German cruiser Emden in a famous ‘ship-versus-ship’ action on 9 November 1914. She subsequently joined the America and West Indies Station until 1916 when she joined the 2nd Light Cruiser squadron in the Grand Fleet. In 1919 she returned to Australia and continued in service until May 1928. She was broken up in Cockatoo Island Dockyard in 1929-30 but her tripod fore mast was removed and mounted on Bradley‘s head in Sydney Harbour where it still stands in 2014 as a memorial

FEATURES OF A LIGHT CRUISER

The only vessel left afloat that fought at Jutland, and the most important British warship of that era, is the cruiser Caroline, currently at Belfast in the care of the National Museum of the Royal Navy. Fortunately the National Maritime Museum’s collection contains this fine 1/48 scale builder’s model of Caroline, as completed in December 1914, which clearly shows how she was designed for a specific purpose. The flared forecastle and hydrodynamic bow allowed her to use her high speed to drive into a rough sea and the large number of light, quick-firing guns mounted forward were intended to facilitate her role as a ‘ destroyer-killer’, defending the Grand Fleet against enemy torpedo-craft in a close range melee. The small, armoured conning tower just forward of the bridge would have given the captain some protection during such a fight but his situational awareness, viewing the action through the narrow slits, would have been minimal. The high forecastle, breakwater aft of the cable deck and gun shields would have given the forward guns’ crews some protection against the elements but, with ammunition supplied and loaded by hand, serving the guns in any sort of sea state would not have been work for the weak or faint-hearted. The Director of Naval Construction originally thought that these vessels would be too lively to use 6-inch guns effectively but wartime experience proved that the after guns could be used and their heavier weight of shell was more effective against the larger destroyers being built by the Germans. Caroline was re-armed with an all 6-inch main armament in 1916.