Coastal Command had really earned its spurs during the Second World War; not only were its allocated squadrons involved hunting U-boats, they also carried out attacks on surface shipping and introduced a fully fledged search and rescue service to the great benefit of those it rescued. Having risen greatly throughout the war Coastal Command would be afflicted by a great contraction immediately afterwards. As many of the command’s aircraft were American Lend Lease, such as the Catalina, their operating units quickly disappeared. Also disappearing almost overnight were those units whose personnel were mainly drawn from the Commonwealth; they decamped home in many cases taking their aircraft with them. Changes were also wrought upon the strike squadrons as they disbanded very quickly.

These changes also set the course for the command’s future thus anti-submarine, search and rescue plus meteorological fights became the post-war duties of Coastal Command. The majority of service aircraft would also be scrapped as the majority were war weary. Beaufighters, Mosquitoes and Halifax patrol aircraft would be rounded up and reduced to produce. These aircraft were replaced by new build Avro Lancasters for use in the General Reconnaissance and air-sea rescue roles while the Short Sunderland was used in a similar role over longer ranges. Joining the Lancaster and Sunderland would be the Handley Page Hastings MR1, which equipped No. 202 Squadron based at Aldergrove while detachments were undertaken to North Front, Gibraltar. Originally the maritime reconnaissance tasks were assigned codenames, which were Epicure from St Eval, Nocturnal from Gibraltar and Bismuth from Aldergrove. When the eight Hastings came into service only the Bismuth task force remained and these were divided into tracks labelled A to O. Sorties were selected by the Chief Meteorological Officer and, on a normal day, only one track was selected and flown. Things changed during exercises and alerts when more missions were undertaken, some of them at night. The Bismuth sorties were being flown when weather satellites were no more than just a dream thus the Met flights were providing very important data not only to the military, but to the nascent and burgeoning airlines starting to cross the Atlantic en masse. The squadron continued to provide this service until August 1964 when it was disbanded.

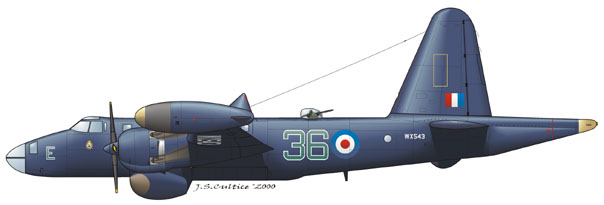

While the Avro Lancaster GR3 was undertaking sterling work it had become obvious that it was becoming long in the tooth thus a more capable replacement was sought. Initially a version of the Avro Lincoln was mooted, however the potential lack of growth in what was basically a bomber design saw this idea sent back to the drawing board. To fill the gap between the Lancaster and its replacement an approach was made to the United States to provide Lockheed Neptunes under the Mutual Defence Aid Programme (MDAP). The version of Neptune supplied to the RAF was equivalent to the US Navy P2V-5 and came complete with nose and tail gun turrets although these were soon improved by the fitment of a clear Plexiglas nose while the tail turret was replaced by a Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD), sting tail. The first of fifty-two Neptunes were delivered to No. 217 Squadron based at St Eval in January 1952, although by April the squadron had moved to Kinloss. This first Neptune squadron was quickly joined by No. 210 Squadron based at Topcliffe in February 1953 while No. 203 Squadron, also at Topcliffe, received its complement by March 1953. No. 36 Squadron was the final unit to form, also at Topcliffe, was reforming in July 1953.

Although the Neptune squadrons were declared operational there were numerous technical problems experienced with the aircraft. Not only did the weapons systems fail to work correctly but some of the electronic systems were not fitted before delivery and the Americans were slow to deliver the missing boxes preferring to give priority to their own forces. By 1955 the Neptunes were fully modified and operational thus they were able to take part in a major exercise over the Bay of Biscay called Centre Board. While the majority of Neptunes concentrated on the maritime reconnaissance role four were utilized for a completely different role that would have far reaching consequences for the future. On 1 November 1952, four Lockheed Neptune MR Mk 1s formed the inventory of Vanguard Flight of Fighter Command based at RAF Kinloss. Their purpose was to research and develop tactics for use by Airborne Early Warning aircraft.

Although disbanded in June 1953 the four Neptune aircraft of Vanguard Flight were reformed as No. 1453 (Early Warning) Flight at RAF Topcliffe in Yorkshire. Despite their anonymous role the Neptunes of No. 1453 Flight appeared like normal aircraft to the public as they retained the full armament of the P2V-5 variant with nose, dorsal and tail turrets. Details of No. 1453 Flight’s operations are scant, leading to speculation that they may have been involved in highly classified reconnaissance missions over or near the Eastern Bloc countries in a similar manner to the US Navy’s Martin P4M Mercator ELectronic INTelligence (ELINT) aircraft, and the ‘Ghost’ North American RB-45 Tornados that flew with RAF crews and markings from RAF Sculthorpe, over eastern Europe to provide radar images of potential targets for RAF and Strategic Air Command (SAC) bombers.

By 1957 there were sufficient replacements available to allow the Neptunes to be returned to America. No. 36 Squadron would disband in February 1957, although No. 203 had gone by August 1956. Other 1957 disbandments included No. 210 Squadron in January while No. 217 Squadron relinquished its aircraft two months later. No. 1453 Flight would end its mission in June 1956 with its machines returning home first.

Not only were the aircraft of Coastal Command changing so were its areas of responsibility. When NATO became operational in April 1951 the AOC-in-C Coast Command also became Allied Air Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Atlantic. This change resulted in HQ Command issuing its projected mid-1953 deployment and equipment. The planned eight Shackleton squadrons covering long-range patrol and maritime reconnaissance were deployed thus: four were allocated to South Western Approaches, three to North West Approaches and a single unit to Gibraltar. All eight units had an aircraft inventory of eight aircraft each. The Short Sunderland was still in service at this time and its deployment included two squadrons each deployed to the southern and northern approaches. As all four units were due to be disbanded or re-equipped their inventory stood at five aircraft each. The Neptune squadrons were concentrated to the east; one was allocated to the north-eastern approaches while the remainder covered the Eastern approaches. In common with the Shackleton units each Neptune squadron was equipped with eight aircraft. Meteorological duties were covered by five Hastings aircraft based at Aldergrove and their duties were set by the Chief Meteorological Officer. By this time the command was operating helicopters for short-range rescue and communications duties, as the operating squadron was divided into flights the sixteen helicopters were dispersed around the country.

Coastal Command also had an extensive support network; most of it was active during peacetime although some organizations were wartime only. Providing training for the front-line squadrons was the School of Maritime Reconnaissance (SoMR) and the Anti-Submarine Warfare Development Unit, both of which moved into St Mawgan when it reopened in January 1951. Should war break out No. 16 Group would be reformed at Chatham to manage the three Neptune units charged with patrolling the eastern approaches while No. 17 Group would reform at Benson for training purposes with No. 19 Group moving to Liverpool to cover the port facilities. The duties of the SoMR included giving sprog maritime aircrew their initial training during a three-month period when 100 hours of training were flown, leaving the Operational Conversion Units to concentrate upon the individual aircraft.

It would be the arrival of the Shackleton that would bring a great leap in capability to Coastal Command. The progenitor of the Shackleton was designed by Roy Chadwick as the Avro Type 696. It was based on the Lincoln bomber and Tudor airliner, both derivatives of the successful wartime Lancaster heavy bomber, one of Chadwick’s earlier designs, which was the current MR aircraft. The design utilized the Lincoln centre wing section and tail unit assemblies bolted to which were the Tudor outer wings and landing gear. These in turn were married to a new wider and deeper fuselage while power was provided by four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. It was initially referred to during development as the Lincoln ASR3. The design was accepted by the Air Ministry as Specification R.5/46. The tail unit for the Shackleton differed from that of the Lincoln while the Merlin engines were replaced by the more powerful Rolls-Royce Griffons driving contra-rotating propellers. The Griffons were necessary due to the increased weight and drag and having a lower engine speed; they provided greater fuel efficiency for the long periods in the denser air at low altitudes that the Shackleton was intended for when hunting submarines better known as loitering.

The first test flight of the prototype Shackleton GR1, VW135, was undertaken on 9 March 1949 at the hands of Avro’s Chief Test Pilot J.H. Jimmy Orrell. In the antisubmarine warfare role, the Shackleton carried sonobuoys, electronic warfare support measures, an Autolycus diesel fume detection system and for a short time an unreliable magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) system. Available weaponry included nine bombs, three torpedoes or depth charges, while defensive armament included two 20mm cannon in a Bristol dorsal turret. The aircraft was originally designated GR1, although it was later redesignated the MR1. The Shackleton MR2 was an improved design incorporating feedback from the crews’ operational experience. The radome was moved from the earlier position in the nose to a ventral position, which improved radar coverage and minimized the risk of bird-strikes. Both the nose and tail sections were lengthened while the tailplanes were redesigned and the undercarriage was strengthened.

The Avro Type 716 Shackleton MR3 was a radical redesign of the aircraft in response to crew complaints. A new tricycle undercarriage was introduced while the fuselage was lengthened. Redesigned wings with better ailerons and tip tanks were introduced, although the span was slightly reduced. To improve the crews’ working conditions on fifteen-hour flights, the sound proofing was improved and a proper galley and sleeping space were included. Due to these upgrades the take-off weight of the RAF’s MR3s had risen by over 30,000lb and assistance from Armstrong Siddeley Viper Mk 203 turbojets was needed on take-off, although these extra engines were not added until the aircraft went through the Phase 3 upgrade. This extra weight and increased fatigue consumption took a toll on the airframe thus the service life of the RAF MR3s was sufficiently reduced that they were outlived by the MR2s. In an attempt to take the design further the Avro Type 719 Shackleton IV was proposed. Later redesignated as the MR4 this was a projected variant using the extremely fuel efficient Napier Nomad compound engine. Unfortunately for Avro the Shackleton IV was cancelled in 1955 as the RAF was shrinking as financial cuts and a contraction of responsibilities was taking place.

The Shackleton MR1 entered service with the Coastal Command Operational Conversion Unit at Kinloss in February 1951. Even as the first Shackletons were entering service with the newly created No. 236 OCU the Royal Navy was trying to scupper the whole of Coastal Command. Their plan was to scrap Avro’s finest and replace them with a fleet of Fairey Gannets operating off small aircraft carriers in midocean while further aircraft would cover the inshore areas. Once the idea had been fully costed it was obvious that the whole plan was fundamentally flawed. Within the command itself the flying boat lobby was also reacting vociferously putting forward the type as a more flexible design, however this too was shot down in flames when it was pointed out that rough sea conditions would either stop them flying or actually wreck the aircraft. Also, flying boats were inherently slow and heavy and the proliferation of runways of sufficient length were springing up all over the world and many of these countries were still susceptible to British entreaties.

No. 224 Squadron based at Aldergrove would be the first unit to receive the Shackleton MR1 in July 1951 replacing the unit’s weary Handley Page Halifax GR6s. Other units that received the Shackleton MR1 included No. 220 Squadron, which initially formed at Kinloss in September 1951 although the unit moved to St Eval in November. In May 1952 No. 269 Squadron based in Gibraltar received its allocation of MR1s while its crews were formed from the nucleus of No. 224 Squadron. By March, however, the entire squadron had returned to Britain taking up residence at Ballykelly. No. 120 Squadron had already been equipped with the Shackleton MR1 in March 1951 while based at Kinloss, although this tenure was short as the entire unit decamped to Aldergrove in April 1952. While at Aldergrove No. 120 Squadron provided the nucleus for No. 240 Squadron, which was also based there. The squadron quickly moved to its new base at St Eval for a few weeks before settling at Ballykelly. No. 240 Squadron would later be renumbered as No. 203 Squadron in November 1958, although this unit would be equipped with the MR1A version that featured slightly more powerful engines amongst other improvements. The Shackleton MR1A was also used by No. 42 Squadron based at St Eval retaining this model until July 1954. No. 206 Squadron was also based at St Eval when it re-equipped with the MR1A in September 1952; the squadron retained this model until May 1958. The last unit to equip with the MR1A was No. 204 Squadron, which traded in its more advanced Shackleton MR2s for the less capable MR1As in May 1958 while stationed at Ballykelly. The MR1As remained in use until February 1960, although by this time the squadron had received some MR2Cs that it retained until March 1971.

The arrival of the Shackleton MR2 would improve the capabilities of the MR squadrons and, in most cases, this new marque would replace the MR1/1A in use. Deliveries to operational units began in 1953 with first deliveries being made to No. 42 Squadron. Initially the squadron retained some of its complement of MR1As until July 1954 as the entry of the MR2 into service was slow, although once the technical problems had been ironed out the type served until 1966. No. 206 Squadron would receive some MR2s in February 1953, although they were dispensed with in June 1954, the unit retaining its complement of MR1As throughout this period. In January 1958 No. 206 Squadron departed St Eval for St Mawgan, remaining there until July 1965 when a further transfer was made to Kinloss. In March 1953 two units would start to accept deliveries of Shackleton MR2s. The first would be No. 240 Squadron based at Ballykelly, although their tenure was short as they were dispensed with in August 1954, the unit resuming operations with MR1s. By November 1958 No. 204 Squadron had been renumbered as No. 203 Squadron still at Ballykelly. No. 203 Squadron would later receive MR2s in April 1962, retaining them until December 1966. The other unit that gained MR2s would be No. 269 Squadron, also based at Ballykelly. The initial allocation lasted until August 1954, the squadron resuming operations flying its original MR1s, which remained the case until October 1958 when a new batch of Shackleton MR2s was received. By December No. 269 Squadron had been renumbered as No. 210 Squadron as part of the contraction of the RAF and the desire of Coastal Command to retain significant unit number plates. No. 210 Squadron would remain as part of Coastal Command and into the early days of Strike Command before disbanding on 31 October 1970 only to reappear the following day as a Near East Air Force squadron.

No. 120 Squadron was based at Aldergrove and had a bit of a hit and miss affair with the Shackleton MR2. The first deliveries were made in April 1953, although all had been returned by August 1954, the unit resuming operations with its MR1s. The squadron received another allocation of MR2s in October 1956 and retained these until November 1958. No. 224 Squadron had slightly better luck with its MR2 allocation that was taken on charge in May 1953, retaining them until disbandment in October 1966.

Ballykelly would also be home to No. 204 Squadron, which had last been in existence as a Vickers Valetta unit before renumbering as No. 84 Squadron in February 1953. The squadron would receive its complement of MR2s in January 1954, which remained in use until May 1958 when they were replaced by Shackleton MR1As. These remained in service until February 1960 by which time the first of the replacement MR2s had arrived. No. 204 Squadron retained its MR2Cs until disbandment in March 1971. The MR2C model differed from the basic MR2 in that it was fitted with the avionics suite from the later MR3. Instead of a base transfer No. 204 Squadron would be disbanded on 1 April 1971 reforming on the same date at Honington. The squadron would supply detachments to Majunga, Tengah and Masirah – the unit had originally been known as the Majunga Detachment Support Unit. The purpose of the Majunga, Madagascar, detachment was to provide aircraft for the blockade of Rhodesia. When the Rhodesian blockade was withdrawn in 1972 No. 204 Squadron was disbanded, its Tengah and Masirah patrols being covered by other units on rotation.

The Shackleton MR2 underwent extensive trials of its avionics and remedial work on its engines, which had a tendency to throw spark plugs from their cylinder heads and required an overhaul every 400 hours. Trials were carried out with the MR2 at the Anti Submarine Warfare Development Unit (ASWDU) covering the performance of the ASV Mk 13 and extensive trials of the RCM/ECM suite before they were cleared for use. The Autolycos diesel fume detection system was also put through its paces before being cleared for service use. Other trials undertaken by the MR2 included the Glow Worm illuminating rocket system, the Shackleton replacing the last Lancaster in operational use. At least one MR2 was utilized for MAD sting trials, although both it and the rocket were dropped. However, the former would equip the later MR3 once all the bugs had been ironed out. Fortunately, the Orange Harvest ECM system, homing torpedoes and the various sonic buoys at least were successful.

The genesis of the Shackleton MR3 would rest upon the need for Coastal Command to cover its projected strength of 180 front-line aircraft by 1956. Although other projects had been put forward the Air Staff finally plumped for the Avro product, issuing OR.320 in January 1953. The first Shackleton MR3 made its maiden flight on 2 September 1955, although production aircraft did not reach service until 1957 by which time some of the contracts had been cancelled. The MR3 was a complete contrast to the earlier models in that it was carried on a tricycle undercarriage, had wing-tip mounted fuel tanks, modified ailerons, a clear view canopy and a sound proofed wardroom to help alleviate the effects of long patrols. Defensive armament consisted of a pair of nose-mounted 20mm cannon, the upper turret being deleted. During 1966 a programme was instituted to upgrade the MR3, the most obvious change being the fitment of a Bristol-Siddeley Viper engine in each outboard engine nacelle resulting in the type being designated the MR3/3.

First deliveries were made to No. 220 Squadron based at St Mawgan in August 1957, although the unit retained some of its MR2s. The squadron had a short existence as it was renumbered as No. 201 Squadron in October 1958. This unit would last a lot longer than its predecessor as it remained as a Shackleton operator until 1970 having moved to Kinloss in December 1965. Close on the heels of No. 220 Squadron to equip with the Shackleton MR3 was No. 206 Squadron, also based at St Mawgan. This unit traded in its 5/3 mix of MR1As and MR2s for a similar number of the new model in January 1958. No. 206 Squadron would also move to Kinloss, departing St Mawgan in July 1965 and remaining there until re-equipping in August 1970.

St Mawgan was also the home for No. 42 Squadron, although this unit would continue to fly some of its MR2s alongside the MR3s after their delivery in November 1965, retaining them until replacement in September 1971. Ballykelly and No. 203 Squadron would be the final recipient of the Shackleton MR3 in June 1966 having first used this model between December 1958 and July 1962. No. 202 Squadron would leave Coastal Command in February 1969 when it was transferred to Luqa, Malta, as part of Near East Air Force (NEAF).

Development of weaponry for the Shackletons continued apace with the Mk 30 Homing Torpedo finally being cleared for service in March 1955 after a period spent trying to get the delicate mechanisms to work properly under operational conditions. With this weapon in service it would see the final demise of the depth charge as the primary anti-submarine weapon. To complement the Mk 30 development work was also taking place on an active homing torpedo codenamed Petane. Unfortunately, delays in clearing the torpedo for service use would result in cancellation and its replacement by the American Mk 43 weapon although the latter’s strike rate was less than that of the British weapon. Also missing from the Shackleton fleet was an airborne lifeboat that had been prominent under the Lancaster GR3s. Although a boat was planned for the Shackleton it was never developed and the fleet was supplied with Lindholme gear that became a standard throughout the command. Avionics for the Shackleton were also under continual improvement, Orange Harvest was constantly being improved while a Doppler system known as Blue Silk was also developed, which was an improvement on the Green Satin system. The primary radar system installed in the Shackleton was the AN/ASV-21 developed for submarine detection; this too was in a state of constant development in order to improve its capability and its ease of operation.