The Assyrians Return

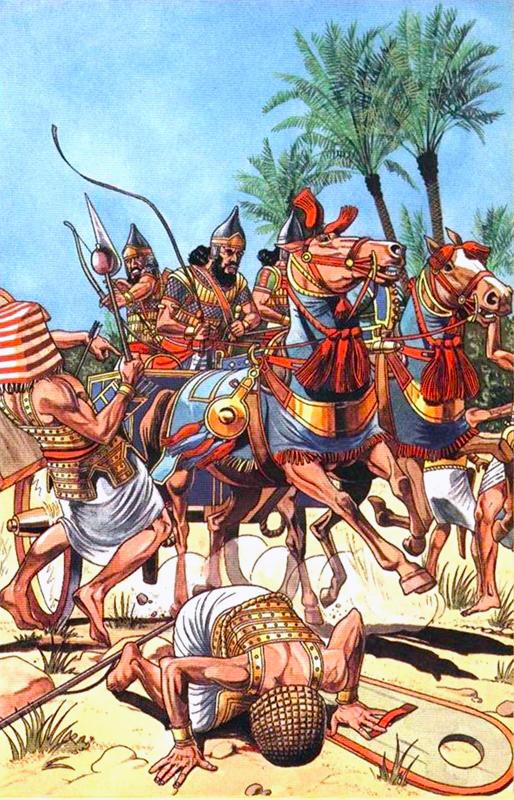

A half-century later in the mid-eighth century B.C. the Assyrians returned, but to a very different world. In addition to their old enemy Urartu, which had taken advantage of Assyrian weakness to extend its influence deep into northern Syria, formidable new powers had appeared. To the east, the Medes, Indo- European immigrants from central Asia, had built a loosely organized kingdom that incorporated many of the other Iranian tribes living on the Iranian plateau and threatened Assyria’s eastern frontier. To the northwest in central and western Anatolia the kingdoms of Phrygia and Lydia occupied the core areas of the second millennium B.C. Hittite Empire and could provide aid to potential rebels among Assyria’s southern Anatolian subjects. The most formidable threat to Assyrian interest in western Asia, however, was the reappearance of Egypt as a major power.

The resurgence of Egypt was the work of the Nubian kings of the twenty-fifth dynasty. Supported by the priesthood of the god Amun at Thebes, they reunited Egypt, suppressing the Libyan chieftains, who had ruled Egypt for over two centuries, and joining Egypt and the kingdom of Kush into a single state. The result was the virtual recreation of the great empire of the New Kingdom, a kingdom that extended for over a thousand miles from near modern Khartoum in the south to the Mediterranean in the north. Within Egypt, the twenty- fifth dynasty marked a period of political and cultural revival in Egypt. Local dynasts were subordinated to royal authority and the military was strengthened. Temple construction and royal art revived. So did funerary and theological literature, all of which were characterized by emulation of archaic Egyptian styles and high-quality workmanship.

Eventually the campaigning of the Kushite (Twenty-fifth Dynasty pharaohs in Syria-Palestine led to direct conflict with a new imperial power: the Assyrians. In 674 BC Taharqa (ruled 690-664 BC) was able temporarily to deter the invading forces of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon ruled 680-669 BC), but in the ensuing decade the Assyrians made repeated successful incursions into the heart of Egypt, and only the periodic rebellions of the Meeks and Scythians – at the other end of the Assyrian empire – prevented them from gaining a more permanent grip on the Nile valley. In 671 Be Esarhaddon captured Memphis describing the event with relish in an inscription at Senjirli:

‘I laid siege to Memphis, Taharqas royal residence, and conquered it in half a day by means of mines, breaches and assault ladders; I destroyed it, tore down its walls and burnt it down. His ‘queen’, the women of his palace, Ushanahuru, his heir apparent, his other children, his possessions, horses, large and small cattle beyond counting, I carried away as booty to Assyria. All Ethiopians I deported from Egypt – leaving not even one to do homage to me. Everywhere in Egypt, I appointed new local kings, governors, officers (saknu), harbour overseers, officials and ad- ministration personnel’ (Pritchard, 1969: 293).

Three years later Taharqa had succeeded in briefly reasserting the Kushite hegemony over Egypt, while the Assyrians were distracted by problems elsewhere. But by 667 B.C. Esarhaddons successor Ashurbanipal (ruled 668-627 B.C.) had penetrated beyond the Delta into Upper Egypt, where he must have severely damaged morale by pillaging Thebes, the spiritual home of the Egyptians.

A fascinating insight into the campaigns of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in Egypt has been provided by the survival of a fragment of relief from Ashurbanipal’s palace at Nineveh which shows the Assyrian army laying siege to an Egyptian city. The details of this scene, such as the depiction of an Assyrian soldier undermining the city walls and others climbing ladders to the battlements, bear strong similarities with Egyptian siege representations described above, showing that ancient siege warfare from North Africa to Mesopotamia used similar tactics and weaponry. The rows of captive soldiers being marched out of the city appear to be mainly foreign mercenaries. In the bottom right-hand corner of the scene a group of native Egyptian civilians are shown clustered together with their children and possessions. The inscriptions of both Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal show that the usual Assyrian practice of deportation was employed, with Egyptian physicians, diviners, singers, bakers, clerks and scribes (as well as prisoners of war and members of the ruling families) being resettled in the Assyrian heartland.

TANWETAMANI (reigned 664-656 BC). Last pharaoh of the Kushite 25th dynasty. His name can be rendered as Tanutamun or Tantamani. After the death of Taharqo and his accession, Tanwetamani led his army to Egypt. The coalition of Delta rulers fled to their hometowns and Tanwetamani regained control of Memphis. He supposedly defeated Nekau I of Sau in battle. Ashurbanipal mustered his army, and in 663 BC marched to Egypt, accompanied by Nekau’s son, Psamtik I, who hoped to be installed in his father’s place. Ashurbanipal appears to have received little opposition, and he pursued Tanwetamani from Memphis to Thebes, which was sacked. Ashurbanipal withdrew, but the Thebans still acknowledged Tanwetamani as pharaoh. In the north, Psamtik I ascended the throne in Sau, and Egypt was divided between the two powers. Ashurbanipal now faced problems in other parts of the Assyrian Empire, and Psamtik began to consolidate his position. His successes ended with a Kushite withdrawal from Upper Egypt, achieved through diplomatic means in the year 9 of both pharaohs.

NUBIAN PHARAOHS

Twenty-Fifth Dynasty c. 750-656 B.C.

Kashta c. 750-736 B.C.

Piye (Piankhy) c. 736-712 B.C.

Shabaka c. 711-695 B.C.

Shebitqo c. 695-690 B.C.

Taharqo 690-664 B.C.

Tanwetamani 664-656 B.C.

The Third Intermediate Period (1069–664 B.C.) was a time when Egypt broke into smaller quarrelling kingdoms or succumbed to foreign invaders. Technically Egypt remained united under the Twenty-first Dynasty (1069–945 B.C.) with its capital at Tanis in the Delta. In reality, the priests of Amun-Ra in Thebes and various local rulers exercised independent control over Upper Egypt. During the latter part of the New Kingdom, many Libyans settled in the Delta and large numbers of Nubians moved into Upper Egypt. The previous ethnic homogeneity of Egyptian society ended even though the newcomers tended to assimilate themselves into the predominant Egyptian culture. Some of the Libyans in the Delta assimilated so well that they took control of Egypt from the Twenty-first Dynasty in 945 B.C.. The new Libyan king, Sheshonq I (945–924 B.C.), began the Twenty-second Dynasty (945–715 B.C.) and continued to use Tanis as his capital. Under Sheshonq I, the fortunes of Egypt briefly revived. The priests at Thebes found that their independence was curtailed. Even more dramatically, Sheshonq I invaded Palestine and restored Egyptian control over the region by defeating the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. He was, in all probability, the Shishak of 1 Kings 14:25–8 and 2 Chronicles 12:1–12, who carried away treasure from Jerusalem during the reign of King Rehoboam of Judah. In popular culture, this would also make him the Shishak of the Indiana Jones adventure Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), who supposedly carried off the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem to his capital at Tanis (but who almost certainly did no such thing). Unfortunately for Egypt, the successors of Sheshonq I were nowhere near as capable. By 818 B.C. a rival Twenty-third Dynasty had arisen in a section of the Delta, along with eventually a very brief Twenty-fourth Dynasty and other regional rulers. Political authority had become so badly fragmented by 750 B.C. that Egypt was exceptionally vulnerable to foreign invasion.

The foreign invaders who established the Twenty-fifth Dynasty over Egypt were the kings of Kush in Nubia. King Piye of Kush (747–716 B.C.) invaded Egypt in about 728 B.C., and reached as far north as Heliopolis but then withdrew without establishing permanent control. Shabaqo [Shabaka] (716–702 B.C.) succeeded his brother Piye as king of Kush and proceeded to invade Egypt and make it part of his kingdom. The Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty was undoubtedly black. It made Memphis its Egyptian capital and, although they never completely stamped out all locally autonomous rulers in Egypt, the Nubian pharaohs attempted to extend Egypt’s control into Palestine and Syria as Sheshonq I had done. This action brought the Nubians into conflict with the Assyrian Empire at the height of its power. In 701 B.C. Shabitqo (702–690 B.C.), the nephew and successor of Shabaqo, attempted to thwart Sennacherib of Assyria’s invasion of Judah. He was defeated, and furthermore he managed to draw Assyrian attention to Egypt. A series of Assyrian attacks on Egypt began in 674 B.C. in which control of the country see-sawed back and forth between the Nubians and the Assyrians. Finally in 663 B.C. Ashurbanipal of Assyria invaded Egypt and sacked Thebes, ending Nubian authority in Egypt for good.

The Kushite state was originally centered around their capital of Napata in what is today the central Sudan, south of what is known as Nubia. In the late 8th c. B.C. the Kushite King Piye, fed up with the degeneracy he claimed was rampant in Egypt proper, led his army north against the disunited Egyptian princes. After several sieges (including amphibious operations) and battles he was able to take control of all of Egypt, founding the 25th dynasty. The Kushite state, especially under King Taharqa, intervened against Assyrian interests in the Levant. This led to several battles in the area of southern Israel. Eventually Taharqa’s forces were driven back into Egypt, and were eventually expelled from Egypt completely when Assyrian armies captured Thebes in 663 B.C. The kingdom of Kush was famous for its horses at this time.

Inevitably, however, the ambitions of the kings of the twenty-fifth dynasty to reassert Egyptian influence in Syria- Palestine also raised the risk of a disastrous collision with the Assyrians.

Beginning in the mid-eighth century B.C., the Assyrians reacted to the new situation with a whirlwind of military campaigns that lasted or almost a century. In rapid succession they defeated their principal enemies: Babylon, Elam, Urartu, and the Neo- Hittite kingdoms of Syria and southern Anatolia. When the peoples of southern Syria and Palestine turned to Egypt for support, the Assyrians crushed Egypt also, driving the twenty-fifth dynasty kings back into Nubia, where their successors became the rulers of the first great empire in the African interior. At the peak of their power during the reign of the king Assurbanipal in the mid-seventh century B.C. the Assyrians ruled the greatest Near Eastern empire up to that time, including western Iran, all of Mesopotamia, southern Anatolia, Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine, and Egypt.

c. 750–656 B.C. 25th Dynasty

c. 750–736 B.C. Kashta. Kushite power acknowledged in Thebes and Upper Egypt.

c. 736–712 B.C. Piye (Piankhy) Tefnakht ruler of Sau expanded power and took control of Memphis. A coalition of Libyan dynasts led by Tefnakht marched into Middle Egypt. Nimlot of Khmunu, a Kushite vassal, joined Tefnakht. Piye sent the Kushite army based in Thebes against Tefnakht. Despite several confrontations, the Kushite army failed to defeat the coalition. Piye led second army to Egypt and besieged Nimlot in Khmunu. A part of the army was sent north and relieved the Kushite ally, Peftjauawybast, who had been besieged within Herakleopolis. Khmunu yielded, and Piye led his army north. Tefnakht fled back to Sau. The Kushites captured Memphis and Piye received the submission of the Libyan dynasts at Athribis; Tefnakht swore his oath of fealty at Sau.

720 B.C. Battle of Qarqar. Sargon II of Assyria defeated Yau’bidi, ruler of Hamath, then marched south, recapturing Damascus and Samaria. The Assyrian army defeated an Egyptian force at the battle of Raphia, and captured the Egyptian vassal ruler of Gaza. The Assyrians were left in control of the Egyptian border at Brook-of–Egypt.

c. 711–695 B.C. Shabaqo

710 B.C. Year 2. Shabaqo and the Kushite army marched into Egypt, defeating the Saite pharaoh Bakenranef in battle.

701 B.C. A joint Egyptian-Kushite army marched to support Hezekiah of Judah in his rebellion against Assyria. The army of Sennacherib defeated them at the Battle of Eltekeh.

c. 695–690 B.C. Shebitqo

690–664 B.C .Taharqo

679 B.C. Esarhaddon led the Assyrian army to Brook-of-Egypt.

678 B.C. Taharqo might have been active in the Levant while Esarhaddon confronted problems in Babylonia.

677 B.C. Esarhaddon attacked Sidon, Taharqo’s ally.

674 B.C. The Assyrian army marched to Egypt but was defeated in battle.

671 B.C. The Assyrians invaded Egypt again. The Egyptian-Kushite army marched to meet them, and there were two battles between Gaza and Memphis. There was a third battle on 11 July 671, at Memphis, which was captured andsacked. Taharqo fled.

669 B.C. Taharqo regained control of Memphis and Lower Egypt and the Assyrian army returned to oust him, but Esarhaddon died en route and the campaign was abandoned.

667 B.C. The new Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, marched his army to Egypt and defeated Taharqo, capturing Memphis. Taharqo fled. There was a rebellion against the Assyrian army by the Libyan dynasts. In response the Assyrians attacked Sau and other Delta cities, massacring the population.

664–656 B.C. Tanwetamani

664 B.C. Tanwetamani led a Kushite army to Memphis, where he defeated and killed the Assyrian vassal, Nekau I of Sau. Nekau was succeeded by Psamtik I.

663 B.C. Ashurbanipal led his army to Egypt and pursued Tanwetamani from Memphis to Thebes, which was sacked. Tanwetamani fled to Napata. The Assyrians withdrew, leaving Psamtik I as their vassal ruler in Lower Egypt.

Taharqa Taharqa (reigned ca. 688-ca. 663 B.C.) was a Nubian pharaoh of Egypt. He was the last ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, the so-called Ethiopian Dynasty, and was driven out of Lower Egypt by the Assyrians as they began to conquer Egypt.

When Shabaka conquered Lower Egypt and thus asserted Nubian rule, he was accompanied by his nephew Taharqa, who was about age 20. Later, during Shabaka’s reign as pharaoh, Egypt confronted the growing might of Assyria on the battlefield. Taharqa was at the head of the Egyptian army, but it is not clear whether the two forces actually fought. Taharqa’s brother Shabataka succeeded Shabaka, and he made Taharqa his coregent in order to assure his succession. About 688 B.C., approximately 23 years after Nubian rule had been imposed over Egypt, Taharqa assumed the throne in his own right.

The next few years were peaceful, and Taharqa moved his capital to Tanis in the Delta so that he could stay well informed about events in the neighboring Asian countries. By 671 B.C. Egypt and Assyria again approached a confrontation, so Taharqa prepared to fight for the continued survival of Egypt. But the Assyrian king, Esarhaddon, crossed the Sinai Desert and defeated Taharqa’s army on the frontier. In 2 weeks he was besieging Memphis. The Egyptian army crumbled under the attack of the better-disciplined Assyrian army, which was armed with iron weapons.

Taharqa fled to Upper Egypt, leaving Esarhaddon to take control of Lower Egypt. Two years later Taharqa re- turned with a fresh army and managed to recover control of the Delta, but this success was short-lived, and Esarhaddon’s successor, Ashurbanipal, drove Taharqa south again. After this final defeat he never again tried to campaign in the north. Egypt then entered into a long era of successive foreign rulers.

During his period of Egyptian rule Taharqa had encouraged many architectural projects, as had his Nubian predecessors. He erected monuments at Karnak, Thebes, and Tanis in Lower Egypt, and he built a number of important temples in Cush, as the Upper Egyptian Nubian state was then known. During the last 8 years of his life in Kush, he continued to foster his architectural interests. In 663 B.C. Taharqa accepted as a coregent Tanutamon, whose precise relationship to him is not clear. The next year Taharqa died and was buried in a pyramid in Nuri. Tanutamon had immediately invaded Lower Egypt himself when he was named coregent, and he managed to gain control of it for almost a decade, only to be driven out by the Assyrians, as Taharqa had been. Although the Nubians had managed to rule Egypt for only about 75 years, their kingdom of Kush in the northern Sudan survived for almost a millennium.