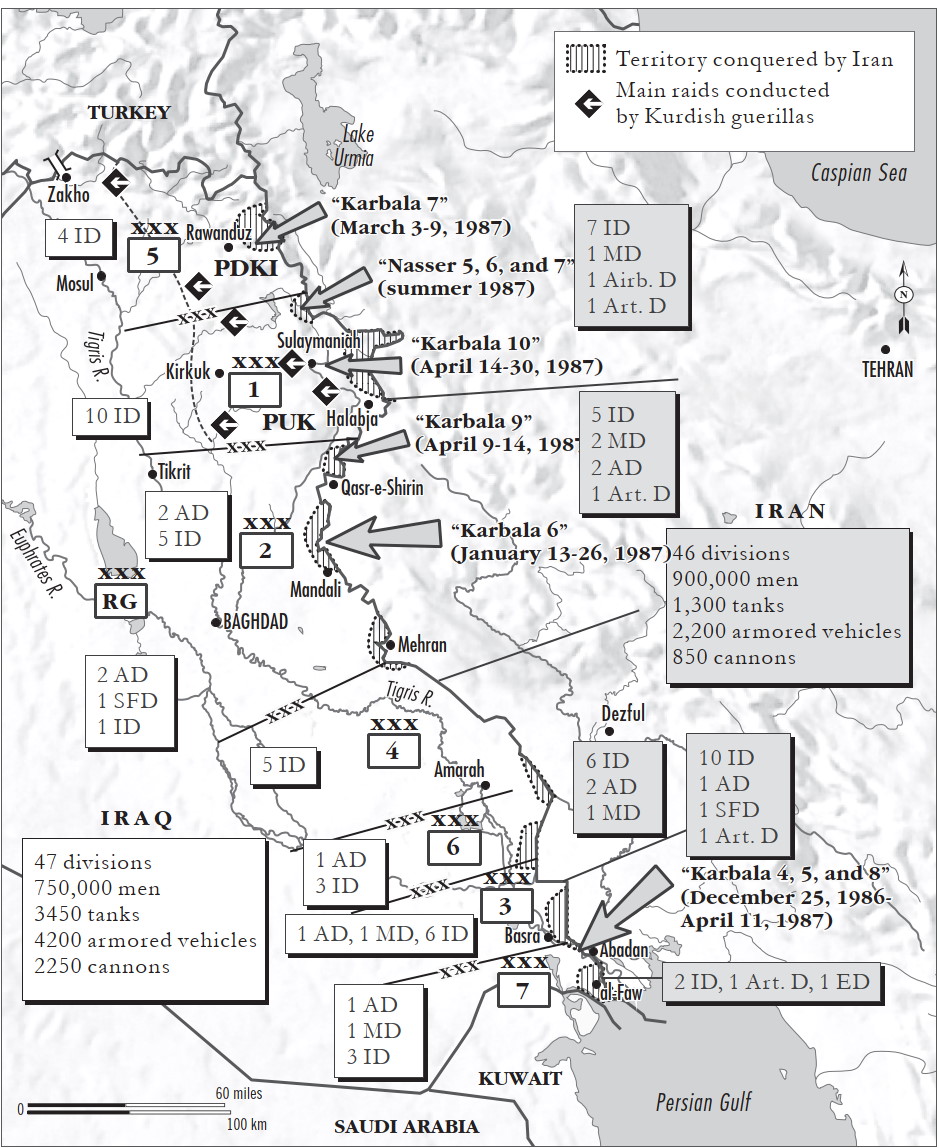

Iran-Iraq front in 1987

In the late fall of 1986 the Iranians prepared another offensive intended to bring Saddam Hussein to his knees. Since Baghdad remained out of range, the Iranian army targeted Basra. Its leaders were convinced that the Ba’athist regime could not survive losing Iraq’s second biggest city. They hoped that the fall of Basra would set off a Shiite insurrection in southern Iraq. They had massed 360,000 soldiers nearby, which were di- vided into thirteen divisions (ten infantry, one commando, one armored, and one artillery), in addition to the 40,000 troops deployed in the al- Faw pocket. The offensive was postponed several times while the regular army and the Pasdaran argued over the method of operations. General Shirazi had proposed a large-scale envelopment maneuver, which he deemed safer and less costly, though it would undoubtedly take longer. Mohsen Rezaee, acting as the spokesman for the Pasdaran, argued for a frontal assault on Basra, which would be more expensive but faster.

The time factor was particularly crucial because the Ayatollah Khomeini had recently decreed a fatwa asking the armed forces to defeat Iraq before March 21, 1987, the next Nowruz, or Persian New Year. This unusual step on the Supreme Leader’s part was obviously aimed at motivating the troops, but also at increasing pressure on Rafsanjani to win or negotiate. The war had lasted too long. Extending it was becoming counterproductive. The mullahs’ power was now firmly established over a fragmented society that no longer had the means to contest the clergy’s stranglehold on public affairs. The opposition parties had been wiped out or muzzled and the Kurdish, Azeri, and Baloch separatist movements put down. Now the authorities needed money to satisfy the people and guarantee social peace. The continuing hostilities were impoverishing Iran. It was urgent to oust Saddam.

The Assault on Basra

Following a heated meeting of the Supreme Defense Council, Rafsanjani imposed the idea of a frontal attack on Basra. The attack would be in two phases: troops would cross the Shatt al- Arab at Khorramshahr to attack the city from the rear, coming from the south, while the main assault would come from Shalamcheh and Hosseinieh, along the river’s eastern bank. During the night of December 24 to 25, 1986, Rafsanjani set off Operation Karbala 4. The 21st Infantry Division, which had been renamed “Prophet Muhammad,” crossed the Shatt al-Arab and landed on Umm al-Rassas Island and the three islets of Bouarim, Tawila, and Fayaz. The division commander, General Ahmad Kossari, was supported by the 41st Engineering Division. His infantrymen immediately ran up against Iraqi troops and were mowed down by their machine guns and mortars. By dawn the Iranians had barely advanced. General Kossari, conscious of his mission’s importance, ordered additional reinforcements deployed. Over thirty-six hours more than 30,000 Pasdaran disembarked on the bridge- head. The Iraqi military high command lost no time in responding, ordering its air force to bomb the floating bridges installed across the Shatt al-Arab. It entrusted the counterattack to the 7th Corps, which was currently assigned to defending the al-Faw peninsula. General Ma’ahir Abdul Rashid, now an ally of Saddam’s family, was in the heart of the action. Heading the 6th Armored Division, he launched a vast outflanking maneuver that wiped out the Iranian soldiers scattered along the river, while some of the 7th Corps’ divisions left their trenches twelve miles (twenty kilometers) away to storm the Iranian bridgehead.

Fierce combat raged for forty-eight hours. Knowing that Basra’s fate was in their hands, the Iraqis seemed unstoppable. On December 27 General Rashid still had full control of the area. His combatants wiped out the remaining pockets of resistance after regaining control of Umm al- Rassas Island and the three neighboring islets. In seventy- two hours they had slaughtered more than 8,000 Iranian fighters, taking only 200 prisoners. The rest had scrambled back across the river. By comparison, the Iraqis’ losses were minor: 800 dead and 2,000 wounded. Glowingly proud of this stunning victory, General Rashid swaggered before his rivals, who often criticized him for bypassing high command and directly obtaining support from Saddam. The dictator was in no position to complain: Ma’ahir Abdul Rashid had just handed him a memorable victory, which he promptly began referring to as the “Battle of the Great Day.”

In Tehran, on the other hand, criticism of Rafsanjani streamed forth from all quarters, including from Ali Khamenei, Ayatollah Montazeri, and General Nejad, the former chief of staff of the armed forces. The Aya- tollah Khomeini even considered removing Rafsanjani as commander in chief of the armed forces, then thought better of it. In ill health, Khomeini needed to rely on the man whom he saw as the only mullah able to stay the course through thick and thin-at least so long as the war lasted. He also knew that the Pasdaran would not understand if he sidelined Rafsanjani- and the Pasdaran were now the country’s most powerful force. The speaker of Parliament was therefore able to pursue his initial plan to attack Basra. Alone against the rest of the regime, he staked his all on committing every available combatant to the battle. He knew his political future depended on it. The fight would be all-out and merci- less. A single catchphrase prevailed: defeat the enemy at any cost. While the Battle of Khorramshahr in 1982 has often been compared to the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of Basra in early 1987 can easily be likened to Verdun: for several months, the belligerents would wear each other down through a hellish confrontation in which they drove their countries’ best and brightest into muddy trenches.

The “Mother of All Battles”

On January 8, 1987, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani launched the Karbala 5 offensive in the sector east of Basra, across from Fish Lake and the artificial channel. Beginning in 1984 the Iraqis had significantly expanded the military layout there. Aside from a succession of minefields, antitank ditches, barbed wire, ramparts, bunkers, and trenches, the sappers had erected a curving embankment around the bridges connecting Basra to the Shatt al- Arab’s eastern bank from the town of Tanuma. The system was supplemented by an electronic early warning system able to detect approaching assailants. General Tala al-Duri, commander of the Iraqi 3rd Corps, had three divisions in the sector: the 8th Infantry to the north of Fish Lake; the 11th Infantry between the lake’s southern tip and the Shatt al- Arab; and the 5th Mechanized, further back near Tanuma. His four other infantry divisions and 3rd Armored Division were deployed a little further north, on the other side of the artificial channel. The city of Basra and the western bank of the Basra-Umm Qasr channel were guarded by several Republican Guard special forces divisions and Popular Army brigades.

At dusk the Iranian 92nd Armored Division engaged with the 8th Iraqi Division, aiming to pin it in place along the border. As soon as night fell the 58th and 77th Pasdaran divisions crossed Fish Lake aboard flat- bottomed boats and disembarked on the other bank, in the middle of the marshes, in order to attack the 8th Division from the rear. They then continued to the artificial channel. Once this maneuver was accomplished, a Pasdaran brigade crossed the canal aboard rubber dinghies and established a half- mile- wide (one- kilometer- wide) bridgehead on the opposite bank, north of Tamura. Concurrently, the 23rd Special Forces Division crossed Fish Lake to establish a second bridgehead facing Tanuma. It was counterattacked by the 5th Mechanized Division.

Meanwhile, further south, three Pasdaran divisions rushed to attack a small quadrangle covering about five square miles (twelve square kilometers) wedged between the Shatt al- Arab, the area south of Fish Lake, and the Jassem Canal, twelve miles (twenty kilometers) east of Basra. Though the Iraqis had expected and prepared for the offensive, they were surprised by the mass of enemy troops: 40,000 combatants, a majority of whom were teenagers, crushed their defenses. At dawn the 11th Division’s infantrymen retreated to a second line of defense erected 1.8 miles (three kilometers) back, near the village of Du’aiji. General Abd al- Wahed Shannan, the division commander, had rallied his troops there and deployed his last brigade.

For forty-eight hours the Iraqis counterattacked with the limited means at their disposal. Cloudy skies forced their air force to fly at low altitude, making it more vulnerable to Iranian anti- aircraft defense: five of its fighters were shot down, while a Tu-16 was destroyed over Shalamcheh by a Hawk missile. The Pasdaran advanced on every front. In the north the 8th Division was surrounded and collapsed. Its general, Abrahim Ismael, was taken prisoner. In the south the Iranians overran the Iraqi second line of defense and seized the village of Du’aiji.

Battle of Basra (December 25, 1986–April 11, 1987)

On January 11 General al-Duri authorized the 11th Division to with- draw behind the Jassem Canal, which connected the artificial channel to the Shatt al- Arab. The waterway formed a natural line of defense, which brought the Basijis to a stop. The Iranian vanguard was now only ten miles (sixteen kilometers) from Basra, within cannon range. Furious that General al-Duri had ordered a withdrawal without his authorization, Saddam Hussein stripped him of his command. Though the dictator had always forgiven al-Duri’s past mistakes, he now needed a genuinely competent individual to supervise the defense of Basra. He appointed Diah ul- Din Jamal as his replacement, a Shiite general who had won his confidence by swearing that he would sooner die than let his native city fall into Iranian hands. Without conferring with General Dhannoun, Saddam Hussein gave General Jamal his operational orders. Dhannoun was offended. The situation grew tense, and Saddam dismissed his chief of staff of the armed forces, asking his entourage who could replace him. Given the circumstances, no one was eager for the job. None of the generals in the high command volunteered. Saddam eventually chose by default, appointing Saladin Aziz, a retired general whose name had been given to him by his advisors. Aziz was an intellectual trained by the British. He had proven himself against the Kurds in the early 1970s and left active duty a few months before the outbreak of war with Iran. Having been summoned out of retirement, he was immediately received by the president, who promoted him to his new appointment. The next day Saddam Hussein, Adnan Khairallah, and General Aziz traveled to Basra to personally assess the situation. The Iraqi dictator authorized the use of chemical weapons and decided to commit the Republican Guard’s “Medina Munawara” armored division to the battle. Realizing that Basra could fall, he ordered its inhabitants to evacuate and asked his generals to prepare a second line of defense along the Euphrates to prevent the Iranians from advancing to Baghdad.

In addition, on January 12 the Iraqi president reignited the “War of the Cities” in a knee-jerk effort to punish the Iranian government and dis- courage it from continuing its offensive on Basra. The Iraqi air force was directed to abandon its fire support missions on the battlefield and its attacks on oil traffic in the Gulf to bomb thirty Iranian cities, including Tehran, Qom, and Esfahan. Though located far from the front, these three cities were raided over several weeks by the ten MiG-25s modified for this type of mission. One MiG-25 was shot down near Esfahan on February 15, 1987. The Iraqis also fired several salvos of Scud missiles at Dezful, Ahwaz, and Kermanshah. The Iranians promptly retaliated by firing Oghab missiles at the Iraqi cities near the front and Scud missiles at Baghdad. North Korea had recently delivered twenty Scuds to Iran and was preparing to ship eighty by the fall. The Iranians retaliated with their artillery, their long-range cannons pounding Basra, Mandali, Khanaqin, and Sulaymaniah. As with previous episodes in the War of the Cities, the latest urban bombing campaign did nothing to shake the belligerents’ resolve.

During the night of January 13 to 14, 1987, the Iranians launched the Karbala 6 offensive in the sector of Sumer. Their goal was to seize the strategic barrier of Mandali, which controlled the road to Baghdad, but especially to force the Iraqis to deploy their reinforcements in this direction, making Basra more vulnerable. General Shirazi personally headed the operation, committing 100,000 men and 600 tanks divided over seven divisions (the 11th Artillery, 25th and 35th Infantry, 40th and 84th Mechanized, and 81st and 88th Armored) to this diversionary battle. For the first time, his general staff also used small drones to fly over the enemy layout, which allowed the Iranians to preserve their precious reconnaissance planes.

The Iraqis had only three infantry divisions facing their opponent. The general in charge of the sector also had three more divisions staggered along the border, but these could not move from their positions without leaving a wide opening in the Iraqi layout. His only operational reserves were the 10th Tank Division and the Republican Guard’s “Hammurabi” Armored Division. In five days the Iranians overran the Iraqi defenses and captured several hills overlooking the abandoned town of Mandali, but failed to break through. The Iraqis counterattacked with their two armored divisions. For the first time in four years the belligerents engaged in a real tank battle. The Iraqis got the upper hand over their adversaries; the Iranian T-59s and T-69s were no match for the Iraqi T-72s, particularly since the former’s tank crews painfully lacked training and motivation. Some had never even fired a shell before, due to Iranian rationing of what had become rare commodities. Yet the Iraqi tank crews were unable to follow through on their success and were beaten back by salvos of TOW antitank missiles. In the final tally each side lost 200 tanks.

On January 17 Saddam Hussein convened his main generals in Baghdad to organize the counteroffensive, which began the next day in the region of Basra. The 3rd Armored Division headed for the marshlands to regain control of the eastern bank of the artificial channel and isolate the Iranian infantrymen entrenched on the other bank, across from Basra. Meanwhile, the 5th Mechanized Division, the 12th Armored Division, and the “Medina Munawara” tank division reduced the two enemy bridgeheads established on each side of Tanuma and pushed the Iranian combatants back into the water. Many did not know how to swim and drowned.