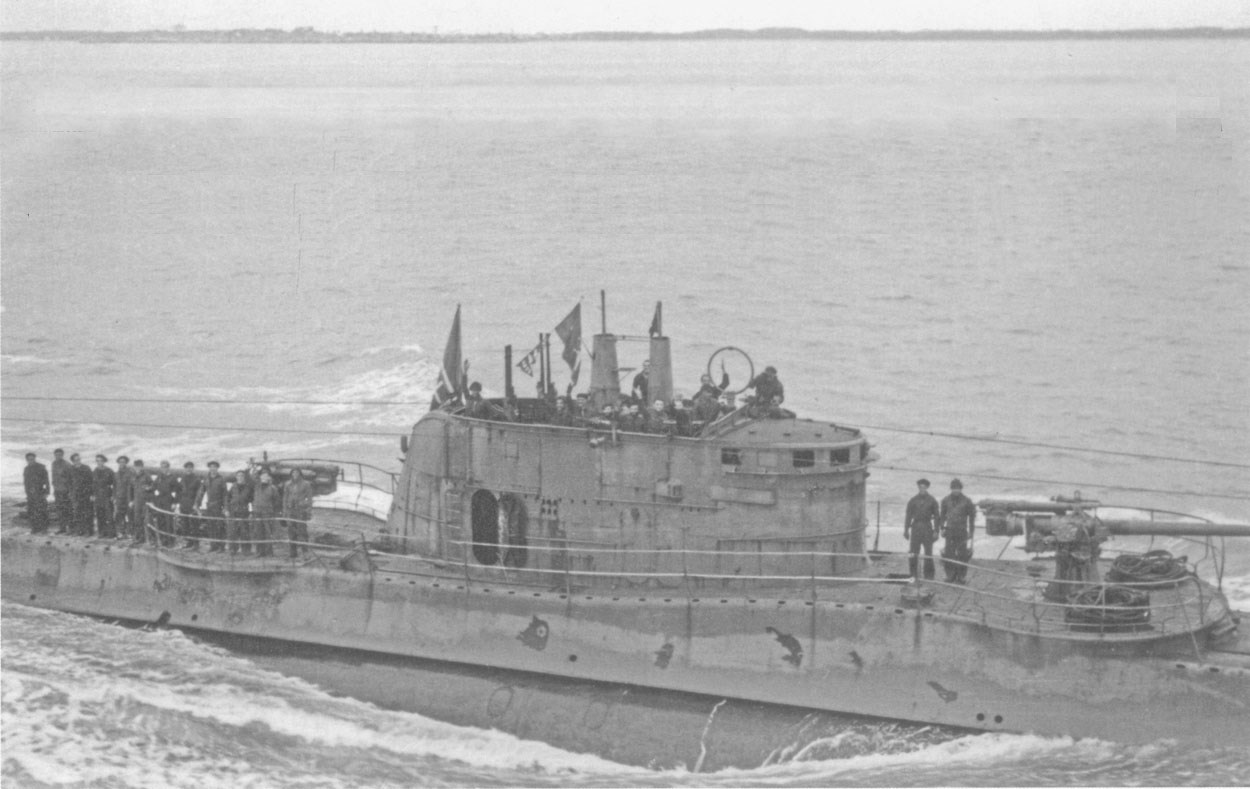

The Barbarigo, seen here in the Garonne estuary returning to Bordeaux after an Atlantic patrol, was the most successful submarine of the Marcello class, sinking seven ships totalling 39,300 grt. With LtCdr. Enzo Grossi in command, the Barbarigo attacked two groups of enemy warships, one off Brazil in May and one off Freetown in October 1942 respectively. Both attacks took place at night, and in each case one US battleship was reported as sunk, thus giving a big boost to Italian wartime propaganda. Actually, the ships attacked by the Barbarigo were much smaller and none was sunk. The two events won LtCdr. Grossi important decorations and awards, but he was stripped of them after the war, sparking numerous controversies which lasted for many years after the end of the Second World War. The Barbarigo was sunk by enemy aircraft in the Bay of Biscay, probably between 17 and 19 June 1943.

Italian submarine of the BETASOM base in the mercantile harbour dry dock, Bordeaux, 1940

Bordeaux Sommergibile — Italian Navy submarine base, set up in August 1940.

BETASOM is an Italian language acronym meaning B Sommergibile or B submarines and it refers to the submarine base established at Bordeaux by the Regia Marina during World War II. From this base, Italian submarines participated in the Battle of the Atlantic, the anti-shipping campaign against Britain.

Axis naval co-operation started after signing the Pact of Steel in June 1939 with meetings in Friedrichshafen and an agreement to exchange technical information. After the Italian entry into the war and the Fall of France, the Italian Navy established a base at Bordeaux, which was within the German occupation zone. The Italians were allocated a sector of the Atlantic south of Lisbon to patrol. The base was opened in August 1940 and the captured French passenger ship De Grasse was used a depot ship. Admiral Perona commanded the base, under control of the German u-boat commander, Doenitz. About 1600 men were based there.

The base could house up to 30 submarines and it had dry docks and two basins connected by locks. Shore barracks accommodated a security guard of 250 men of the San Marco Battalion.

A second base was established at La Pallice to allow submerged training, which was not possible at Bordeaux.

Operational detail

Three Italian submarines patrolled off the Canary Islands and Madeira from June 1940, followed by three more off the Azores. When these patrols were completed the six boats returned to their new base at Bordeaux. Their initial patrol area was the North western Approaches and at the start they out-numbered their German allies’ submarines. Doenitz was pragmatic about the Italians, seeing them as inexperienced but useful for reconnaissance and likely to gain expertise.

He was disappointed. The Italian submarines sighted convoys but lost contact and failed to make effective reports. Even when assigned to weather reporting – critical for the war effort on both sides – they failed to do this competently. Fearing that German operations would be prejudiced, Doenitz reassigned the Italians to the southern area where they could act independently. In this way, about thirty Italian boats achieved some success, without much impact on the critical areas of the campaign.

German assessments were scathing. Doenitz described the Italians as “inadequately disciplined” and “unable to remain calm in the face of the enemy”. When the British tanker British Fame was attacked by the Malaspina, “the officer of the watch and lookouts were on the bridge and the captain was dozing in a deckchair below”. It took five torpedoes to sink the tanker and, at one point, the tanker’s gunfire forced the Malaspina to submerge to safety. The Italians towed the lifeboats to safety, an act worthy of praise, but one against Doenitz’s orders and leaving the submarine open to attack for 24 hours.

Seven Betasom submarines were adapted to carry critical war materiel from the Far East (Bagnolin, Barbarigo, Cappellini, Finzi, Finzi, Giuliani, Tazzoli, Giuliani and Torelli). Two were sunk, two were captured in the Far East by the Germans after the Italian surrender and used by them and a fifth was captured in Bordeaux by the Germans, but not used.

Altogether, thirty-two Italian boats operated in the Atlantic between 1940 and 1943, of which sixteen were lost as shown in the following list:

1940: Tarantini, Faà di Bruno and Nani.

1941: Marcello, Glauco, Bianchi, Baracca, Malaspina, Ferraris, Marconi.

1942: Calvi and Morosini.

1943: Archimede, Tazzoli, Da Vinci and Barbarigo.

Of the sixteen remaining boats, on 8 September 1943 the Cagni was in the southern Indian Ocean, and made for the Allied port of Durban, South Africa; prior to that, other submarines had returned to the Mediterranean and only seven boats were in Bordeaux as of mid-1943: Cappellini, Tazzoli, Giuliani, Barbarigo, Finzi, Bagnolini and Torelli. All were scheduled to be converted into transport submarines to ferry strategic materials to and from the Far East and, in fact, three one-way transport missions were carried out successfully. Tazzoli and Barbarigo were sunk on their first missions, while Cappellini, Giuliani and Torelli managed to reach Singapore between July and August 1943; after the Armistice they were seized by the Japanese, and later handed over to the Kriegsmarine. The Giuliani was lost in 1944, while the Cappellini and Torelli came under Japanese control after May 1945 and were scrapped after the war. The two last transport boats – Bagnolini and Finzi – were being overhauled at Bordeaux when the Armistice was proclaimed, and were thus seized by the Germans. Altogether, the thirty-two submarines of the Regia Marina operating in the Atlantic between 1940 and 1943 sank 101 Allied merchant ships totalling 568,573 grt; an additional four freighters (35,765 grt) were damaged. The most successful submarine was the Da Vinci, with sixteen ships totalling over 120,000 grt, and other boats sank from one to seven ships each; only four submarines (Faà di Bruno, Glauco, Marcello and Velella) sank no ships at all.

End

The base was bombed by the British on several occasions

After the Italian Armistice in September 1943 the base was seized by the Germans. Some of the Italian personnel joined the Germans independently of the Italian Social Republic.

List of submarines operating from Betasom

All Italian submarines based in the Mediterranean had to transit the Straits of Gibraltar to reach the Atlantic. Twenty eight did this sucessfully, without incident. Another four boats based in Italian East Africa reached the base after the fall of the Colony in 1941.

Transferred from the Mediterranean in 1940

Malaspina

Tazzoli

Calvi

Finzi

Bagnoli

Giuliani (this boat was transferred for a time to Gdynia to train Italian submariners in German Navy techniques)

Tarantini

Marconi

Da Vinci

Torelli

Baracca

Marcello

Dandolo

Mocenigo

Veniero

Barbarigo

Nani

Morosini

Emo

Faà di Bruno

Cappellini

Bianchi

Brin

Glauco

Otaria

Argo

Velella

The Cagni was transferred in 1942

Transferred from the Red Sea Flotilla

Archimede

Perla

Guglielmotti

Ferraris

In 1941 it was decided to return some of the boats to the Mediterranean. The Perla, Guglielmotti, Brin, Argo, Velella, Dandolo, Emo, Otaria, Mocenigo, and Veniero Glauco made the passage but Glauco was sunk by the Royal Navy.

Transport Submarines

Hitler asked Admiral Doenitz to find a cheaper solution to the Far East transport problem. Unwilling to remove from the operation theatre some good fighting vessels, Admiral Doenitz turned to Italy and proposed an agreement to Mussolini himself in order to exchange a number of submarines. Seven Italian ocean-going U-boats whose base was at Betasom ( Bordeaux ) were, according to Doenitz, too large and unfit for modern fighting techniques but they could still be converted into cargo ships. Mussolini accepted the proposal and within few months seven Italian vessels were sent to the yards for a total refitting.

In the second half of May 1943, as soon as the hulls had been thoroughly refitted, the first Italian cargo submarine sailed from Bordeaux soon followed by some more, all awaited by a tragic doom. Two of them, in fact, ( the Tazzoli and the Barbarigo ) disappeared in the sea, soon after leaving, probably sunk by allied aero naval forces, while the Giuliani and the Torelli, caught by the armistice of September 8th, when they were still in Malayan port of call, were seized by German naval forces operating in that base.

The apparent misfortune of the Italian submarines gave, however, a good opportunity to the Japanese who could recover from the captured ships 355 tons of strategic materials shipped from Germany, that is 55% of the total cargo. On the contrary the 377 tons of rubber and the 184 tons of pewter which had already been stowed in the holds of the three Italian ships never got to Germany because the Germans didn’t feel like using such worn out means of transport.