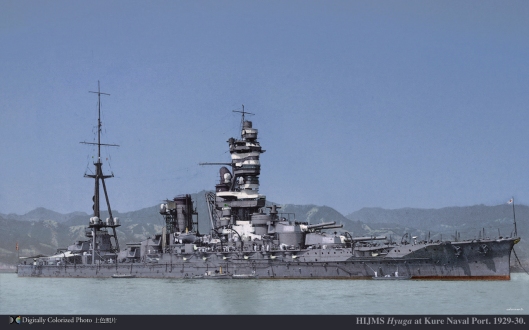

From 1942 the Japanese floated several large new fleet carriers and built the world’s largest carrier – the IJN Shinano – utilizing the hull of an unfinished superbattleship. It would be sunk by a USN submarine while still in harbor. Deeper into the war the IJN concentrated on nine seaplane carriers and on converting various tenders and other large hulls to carriers, including three converted passenger liners. It also partially converted two battleships, the IJN Ise and IJN Hyuga. But when the Navy ran out of naval aircraft, these ships were reconverted to fight as battleships. What the IJN badly neglected before the war, and did not produce during the conflict, was sufficient purpose-built escort ships or a sound convoy doctrine. It additionally lacked advanced ship and naval aircraft radars. The gap was not made up by trying to acquire enemy naval radar technology by such desperate means as diving to British or American wrecks to recover the technology. The IJN also lacked an adequate pilot training system, so that it would be unable to maintain a supply of quality aviators after losing too many frontline pilots in the great carrier clashes of 1942-1943. Whole Japanese Army garrisons were left unsupplied by the Navy, effectively abandoned as the war passed them by. From 1937 IJN officers felt aggrieved that Japan was dragged by the Army into the quagmire of the China War. After 1941, Army officers believed they had been misled by the IJN into agreeing to a ruinous war in the Pacific. Both views were correct.

The 311,000 officers and men of the IJN at the end of 1941 were high quality: nearly 80 percent of crew had enlisted as volunteers. As the IJN embarked upon the Pacific War it was a highly motivated professional service, confident in its ships, aircraft, and excellent torpedoes. It was overconfident in its primary doctrine, however. Because IJN planners realized they could not win a long naval war against the USN, they planned for a war in which they brought the main enemy fleet to a ‘decisive battle’ and destroyed it, thereby evening the naval odds. This doctrine relied overmuch on battleships, even after the Royal Navy showed the vulnerability of large capital ships to naval air attack at Taranto in November 1940, and the Japanese demonstrated the same thing at Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and in sinking HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales. The first chance to test the doctrine in a fleet action came at the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 3–8, 1942), but that encounter was indecisive. Next came the Battle of Midway (June 4–5, 1942), where the IJN suffered a catastrophic loss of fleet carriers and naval air power from which it never fully recovered. The Guadalcanal campaign (1942–1943) provided more opportunities for small fleet actions in the battles of Cape Esperance (October 11–12, 1942); the Eastern Solomons (August 23–25, 1942); Santa Cruz (October 26–27, 1942); and the naval Battle of Guadalcanal (November 12–15, 1942). As Samuel Elliot Morrison noted in his monumental history of the naval war, the old tactics of line of battle were rendered obsolete by advances in antiship aircraft, which demanded evasive action and rendered it “impossible to maintain the line under air attack.” Yet, the old battleship wing of the IJN still clung to line of battle dogma and the “decisive battle” delusion as late as the great fight at Leyte Gulf in 1944.

Just as tellingly, the IJN deployed its submarines not to intercept enemy troop and resupply columns but to attack and reduce the number of the enemy’s capital ships in preparation for the always elusive “decisive battle” it sought between surface fleets. Japanese submarines of all types, including midget submarines, were deployed to harry the ships of the U.S. Pacific Fleet rather than to destroy merchantmen and force the USN to redeploy destroyers and shipyard capacity to building escorts. Even this ill-advised submarine strategy had to be abandoned from 1943, as IJN submarines were converted into supply ships for stranded garrisons along the coast of New Guinea and across the South Pacific. That need also affected construction, so that late-war Japanese submarine designs shifted away from lethality to increased cargo capacity. To partly compensate for lost naval combat power, a base for 11 German attack U-boats and a supply boat was established at Penang in mid-1943. More U-boats arrived later, as Indian Ocean hunting was safer and more profitable for U-boats by that point than plying dangerous Atlantic waters. Effective Axis submarine cooperation did not survive past the destruction of the last Kriegsmarine Milchkühe (“Milk Cows”) supply boats in Asia in the spring of 1944. The last four German and two converted Italian submarines in Asia were seized by the IJN when Germany surrendered in May 1945. Efforts to persuade Dönitz to send more boats to the Pacific failed, as he instead instituted REGENBOGEN, scuttling the U-boat fleet. At its maximum, the IJN deployed a fleet of 200 submarines. Poor doctrine and the shift from an attack to a supply role meant that Japanese submarines sank only 171 enemy ships to the end of the war. A handful were important warships and a few were military auxiliaries, but nowhere near enough warships were sunk or damaged to turn the fortunes of the naval war. The cost to Japan of that effort was to leave hardly dented the enemy merchant marine. The IJN lost 128 lost boats and crews in a submarine effort that barely registered against the enemy order of battle. The United States captured two I-400 “Toku”-class boats a week after the surrender. At 400 feet in length, they were larger than any submarine built before nuclear vessels in the 1960s. When the Soviet Union asked to inspect them, the USN took the boats to sea and sank them.

The IJN commissioned kamikaze suicide pilots in 1944. It also prepared lines of Fukuryu, or “Special Harbor Defense and Underwater Attack Units,” comprising suicide divers armed with mines or torpedoes. They would have greeted any Allied attempt at amphibious landings on the home islands. The IJN deployed suicide motor boats in the Philippines and at Okinawa, but to little effect. By the end of the war the IJN lost 332 out of 451 warships, including submarines, it put to sea. A paltry 37 warships of the once feared IJN remained operating upon the surrender, and most of those were in safe Korean or Chinese ports, hiding from enemy bombers and submarines. What was left of the Imperial Japanese Navy was formally dissolved on November 30, 1945. Japanese warships were hardly seen again in north Asian waters—beyond minimal coastal patrols—until the 1990s. On June 24, 2008, the first IJN warship since World War II docked in a Chinese port, carrying earthquake relief supplies. Its arrival on a mission of peace was regarded as a major breakthrough in Sino-Japanese relations, dating back over 100 years.

Suggested Reading: Sadao Asdada, From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (2006); David Evans and Mark Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (1997