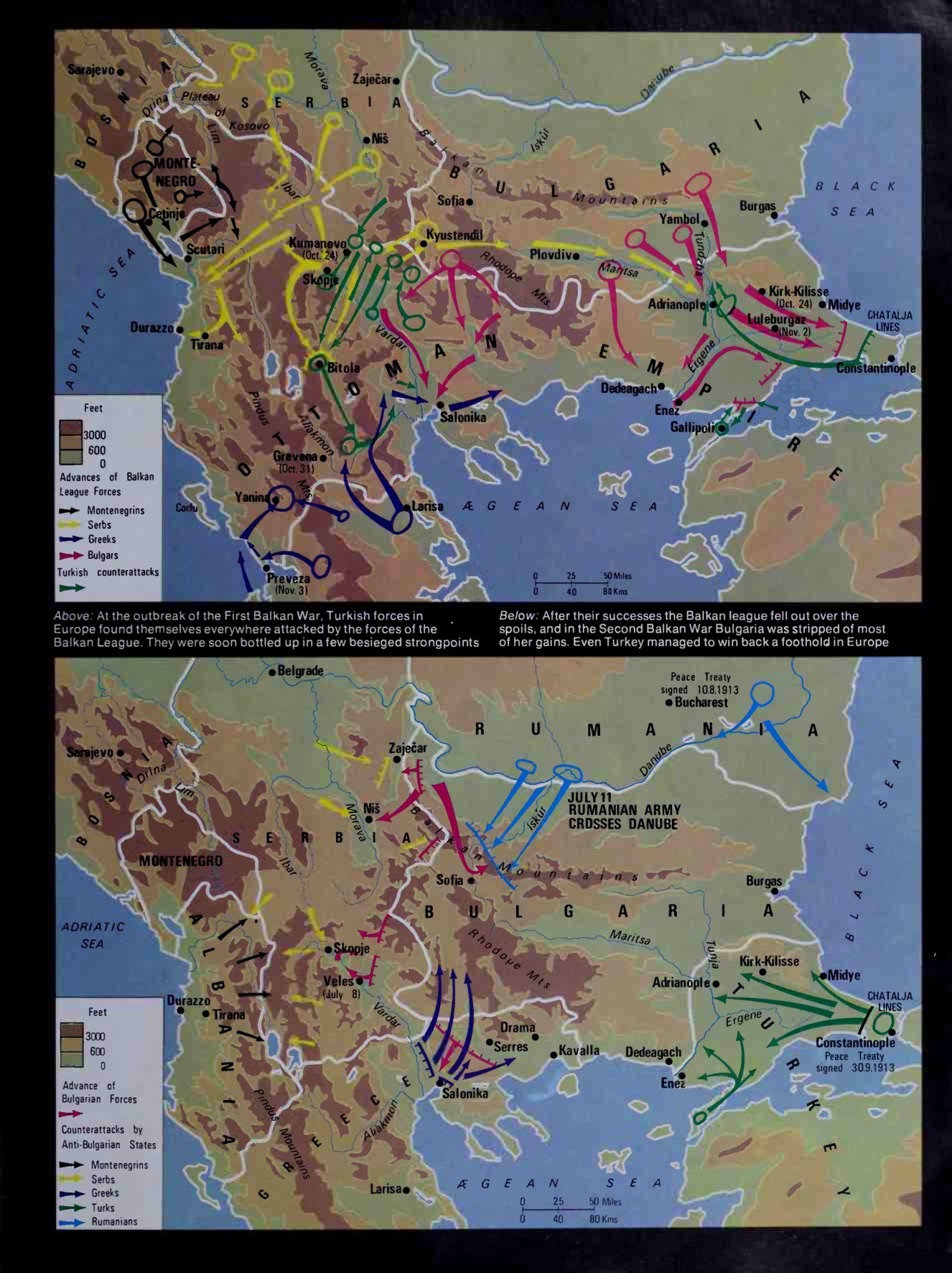

The Balkan Wars 1912/1913

Following the dynastic change in Serbia in 1903, tensions with Austria-Hungary began to rise slowly, not the least because of Russia’s growing influence in the Balkans. Emperor Franz Joseph was convinced that he could still curb Belgrade’s foreign policy ambitions even if it was no longer possible to control them. But the situation reached a turning point in 1912.

In March of that year, Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro, orchestrated by Russia, formed the Balkan League, a system of bilateral, mutual assistance treaties that aimed to deprive the sultan of his remaining European possessions. From Vienna’s point of view, the patronage of the Russian czar toward these Christian states expanded his sphere of influence to a dangerous degree. Serbia turned itself into the gravitational center of South Slavic national movements by demanding outright the separation of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Since Russia was also searching for allies in Galicia, Bohemia, and Bukovina, Austria-Hungary felt itself surrounded by hostile forces.

On 8 October 1912, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Ten days later, the other members of the Balkan League joined it. Their troops moved quickly to the southern Balkan region in the direction of Kosovo and Macedonia. That winter the Montenegrin army reached Shkodër, and the Serbs advanced down the Albanian coast to Durrës. However, Serbia’s grab for Kosovo and Macedonia was not only criticized by Bulgaria and Greece, which also harbored territorial claims to this region, it was also condemned, especially by the Albanian national movement. Founded in 1878, the League for the Defense of the Rights of the Albanian Nation, commonly known as the League of Prizren, had demanded autonomy within the Ottoman Empire for years without success and had even assumed power in Kosovo for a short spell in 1881. In 1911, unrest erupted there, and in the spring of 1912, a revolt. Now the creation of an Albanian nation state was even being discussed.

The Balkan armies committed unfathomable atrocities against the civilian population as they conquered the Ottoman areas. They expelled, persecuted, and sometimes even annihilated unwanted minorities to usurp territory to which there were no legitimate claims. Such “ethnic cleansing,” a euphemistic term for mass atrocities, had occurred since the beginning of the nineteenth century during the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of modern nation-state building. Since the Serb uprisings in the early nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of people had been uprooted, and violent policies of homogenization continued thereafter when ethnic homogeneity became the mantra of a strong and effective nation-state in Europe. In a nationalist age, the makeup of a population served to justify one group’s territorial claims over those of another. Leon Trotsky reported how “the Serbs in Old Serbia … are engaged quite simply in systematic extermination of the Muslim population” so as to correct the ethnographical statistics to their favor. The armed forces of the other countries also undertook “ethnic cleansing” in order to destroy any resistance. “Houses and whole villages reduced to ashes, unarmed and innocent populations massacred … with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians,” documented an independent commission of inquiry. Throughout the twentieth century, such acts of violence would reoccur whenever conquests brought regime change or empires and states fell apart, particularly during the Second World War and the Yugoslav wars of succession in the 1990s.

The Great Powers worked feverishly to come up with a containment strategy. However, by December 1912 it had become clear that the status quo could not be reinstated in the Balkans. Instead, a dangerous crisis developed in Austro–Russian relations. Ultimately, Vienna succeeded in blocking Serbia from gaining any access to the Adriatic and, for this purpose, recognized the independence of the new state of Albania, declared by the Albanian National Congress in November 1912 in Vlorë. On the basis of these developments, the warring sides signed the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913, through which the sultan lost most of his European possessions.

Serbia refused to accept the situation and demanded parts of Macedonia as compensation for the loss of territorial claims in Albania, thereby destroying the Balkan League. King Ferdinand of Bulgaria attacked Serbia and Greece on 29 June 1913, was defeated, and had to accept painful territorial losses in the Treaty of Bucharest, signed on 10 August 1913. Albania was given the status of a sovereign principality under the control of the Great Powers and their governor, German Prince Wilhelm zu Wied. Still, about 50 percent of the Albanian population lived outside the boundaries of this new state.

In light of Serbia’s successful expansion in the Balkan wars, encouraged by Russia, the view of the “hawk” faction at the Viennese court persevered: now Serbia was said to pose an existential threat to the dual monarchy that could only be eliminated by force. From this point on, the Serbian danger, supposedly initiated by Russia, became the leitmotif of Austro-Hungarian politics in the Balkans. For Serbia, however, the wars had established it as a regional hegemonic power, which thus immensely boosted its national self-confidence. Its territory had expanded by 81 percent with the annexation of Vardar-Macedonia, Kosovo, and Sandžak, its population by nearly 50 percent to about 4.3 million. Belgrade had achieved a grandiose military triumph and reconquered the historic and emotionally significant “Old Serbia” with Kosovo and parts of Macedonia, where once the heart of the medieval Serbian empire lay. However, the victory had come at a high price. In both wars the country lost 14,000 combatants in battle. An additional 22,000 soldiers died from injuries and disease, and 54,000 were wounded. The costs equaled a sum three times greater than the national budget.8 Serbia was exhausted, financially drained, and confronted with new domestic problems caused by a half million new Albanian and Turkish citizens. Authorities settled about 12,000 Serb families in the new territories, and thousands of Muslims fled. The Serbs ruthlessly combated the active resistance put up by Albanian rebels, the Kachaks, starting in 1913. In addition, guerrilla warfare with the Macedonian irregular troops of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization started in 1914. War and uprising left the population destitute.

Among the Serbs and Croats still living under Habsburg rule, the Balkan wars had an enormous mobilizing impact. “Not only in Serbia itself, but also in the Austro-Hungarian regions inhabited by South Slavs did people believe that the collapse of Austria-Hungary was imminent and that Yugoslavia could be created only from Belgrade with the help of the Serbian army and its allies,” concluded Alexander Hoyos, then the chef de cabinet at the Austrian Foreign Ministry. In March 1913, a confidential report submitted to the emperor and his government stated: “The South Slavic idea, meaning the idea of the Serbo-Croatian fraternization … has now reached the highest leadership and … is not only the solution for all segments of the population in political matters, but also in cultural and economic ones as well. This is true not only for Croatia and Slavonia, but also for Bosnia and Herzegovina and particularly for Dalmatia, where a revolutionary, antimonarchical spirit has promptly gained ground.”

Serbia’s national agitation and its drive for expansion endangered both the domestic stability and the foreign security of Austria-Hungary. In April 1913, negotiations commenced between the Serbian and Montenegrin governments on unification, which would have given Belgrade its long-sought access to the sea. Furthermore, Serbia took possession of Macedonia and hence acquired parts of the Oriental Railway in 1912/1913. Since the Habsburgs owned 51 percent of the railway, they suffered highly aggravating financial losses. However, what troubled them the most was Russia’s political patronage in the region, because this affected the power and alliances of the Habsburg Empire and curtailed its military discretion in handling defiant Balkan states. For Austria-Hungary, relations with Serbia were increasingly becoming a question of survival, and each success enjoyed by Serbia further reinforced this view.

The Balkan wars accelerated the militarization of Austria-Hungary’s Balkan policy. It was becoming increasingly clear that a military offensive was being taken into consideration as part of its strategy to prevent the further expansion of Serbia’s influence in the region. Vienna issued ultimatums both in the spring and fall of 1913 that forced Montenegrin and Serbian troops to retreat from Albanian territory, which then reconfirmed the Austrians’ view that force was the only language Belgrade understood. When control over the annexed provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina threatened to slip from its grasp in the summer of 1914, Vienna resorted to the means of “surgical intervention against the pathogenic agent” Serbia. What was at stake seemed to be nothing less than the domestic stability of Austria-Hungary, if not the survival of the monarchy itself. In a memorandum dated 24 June 1914, the Foreign Ministry, encouraged by Germany, urged the emperor to take an aggressive foreign policy course. This memorandum shows that, even before Austria-Hungary faced the crisis that would unfold in July, the leadership had decided to use the aggressive strategy worked out back in 1906 by General Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf.

Vienna’s policy was developed in the context of pressing considerations and concerns involving the Balkans and foreign alliances, the foremost of these being its troubled relations with Romania, a rivalry with Italy over Albania, the danger that the Balkan League would be revived to counter Austria-Hungary, a possible unification of Serbia and Montenegro, and the growing influence of Russia in the region. Several factors paved the way for a “great war”: the division of Europe into two hostile blocs; the arms race and imperial expansion in Asia, Africa, and Latin America; growing social and domestic conflicts; and finally, aggressive war plans, inaccurate military speculations, and diplomatic mismanagement. War would offer the chance to neutralize Serbia. All that was needed was the appropriate opportunity to spark a conflict, and that occurred on 28 June 1914 with the assassination of Austrian crown prince Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

Assassination and the July Crisis

Shortly after 1:00 p.m. on 28 July 1914, the Serbian prime minister, Nikola Pašić, was eating lunch at the Café Evropa in Niš when a gendarme handed him a simple telegram containing Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war. Tensions had been great and preparations for war had intensified in the weeks since the 19-year-old Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip had shot the Austrian crown prince, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo. That spring, members of the Young Bosnia movement had felt deeply provoked by the announcement that the royal couple would visit the occupied provinces to observe military maneuver exercises precisely on the anniversary of the symbolic and emotionally charged Battle of Kosovo. On the morning of 28 June, seven young conspirators armed with bombs and weapons positioned themselves along the Appel Quay. It was due to pure coincidence and especially the bungling security measures of the police that this amateurish tyrannicide was successful.

The assassins and their instigators were seized shortly afterward and later tried along with about 180 other sympathizers. Princip and his codefendants repeatedly asserted that they had planned the assassination all by themselves and had only been handed the weapons in Serbia. Yet apparently they had very different political and private motives. Princip confessed that he had been determined since 1912 to carry out an assassination of some person of high standing who represented power in Austria. “I am not a criminal, because I just eliminated an evildoer,” he claimed on 12 October 1914. He and his accomplices further stated that Franz Ferdinand was an “enemy of the South Slavs,” that the archduke was responsible for the state of emergency and all trials of high treason, and that poor people were becoming even poorer with every passing day. They all sought to free Bosnia from the Habsburg monarchy and unify all South Slavs into a single state, so that Yugoslavs would live together as one nation.

The Austrian prosecutors refused to accept that the anti-Slavic politics of Austria-Hungary had motivated these members of the Young Bosnians to carry out the assassination. They attempted to prove that the Serbian government had planned and assisted the assassination of the heir to the Habsburg monarchy because the crown prince allegedly wanted to reform the empire in a way that would have taken the wind out of the sails of Serb nationalism. But nowhere in their testimonies do the assassins ever say that they murdered Franz Ferdinand because of his (actually nonexistent) plans to establish trialism. To date no evidence has been found to prove either that the assassination was the work of the Serbian government or that Russia was the real force behind Serbia’s politics. On the contrary, two weeks before the assassination, Prime Minister Nikola Pašić had pushed to halt the illegal smuggling of weapons to Bosnia-Herzegovina and to scrutinize the activities of the Black Hand.

On 28 October 1914, the Austrian court sentenced the three main perpetrators to twenty years in a maximum security prison camp located in the Bohemian city of Theresienstadt. Their punishment was to be intensified by a day of fasting each month and by confinement in a bare-bones, completely dark cell every 28 June. All three died in prison as a result of the inhuman conditions there.

The Serbian government in Belgrade attempted to de-escalate the situation since it had long been concerned that Vienna was looking for a pretext to attack. It expressed its deep regrets and condolences and assured Vienna that Serbia would immediately investigate the circumstances of the assassination. At the same time, it stated unequivocally that the Serbian government had nothing to do with the murder. The Russian envoy Strandtmann reported on 23 July 1914 from Belgrade that an aggravation of Austrian-Serbian relations “was viewed in Belgrade as being not only unwanted, but also as dangerous for the survival of the kingdom itself.”

Diplomats at Vienna’s Foreign Ministry on Ballhausplatz were indeed pondering “what demands could be made that would be thoroughly impossible for Serbia to accept.” On 7 July, the Ministerrat für Gemeinsame Angelegenheiten (Council of Ministers for Common Affairs) urged the stipulation of unfulfillable conditions, “so that a radical solution in the direction of military intervention could be initiated.” Twelve days later, it decided to prune Serbia to a rump state dependent economically on Austria-Hungary by partitioning as much of Serbian territory as possible with Bulgaria, Greece, and Albania. Even though it is accurate to say that the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne on 28 June 1914 was but the trigger that discharged the full force of mounting international competition between the major powers, and that Emperor Franz Joseph would never have risked the attack on Serbia without the support and public encouragement of Germany, the conflict between Austria and Serbia that had been building since 1908 possessed its own explosive logic.

On 23 July around 6:00 p.m., the Austrian envoy Baron Giesl delivered an alarming note in Belgrade. In it, Vienna accused the Serbian government of complicity in the assassination and issued a ten-point ultimatum in which it demanded that the propaganda aimed against Austria-Hungary be condemned and all irredentist activities be prosecuted. In addition, it demanded that Serbia “agree to the cooperation in Serbia of the organs of the Imperial and Royal Government in the suppression of the subversive movement directed against the integrity of the Monarchy.” Serbia was to answer within forty-eight hours.

In these forty-eight hours, Nikola Pašić composed—with the help of his minister of domestic affairs, Stojan Protić—a truly masterful answer that commanded quiet respect even in Vienna. He delivered the note personally to the Austrian ambassador shortly before the clock struck 6:00 p.m. The note was conciliatory, nearly apologetic, in all points except one: “As far as the cooperation in this investigation of specially delegated officials of the I. and R. [Imperial and Royal] Government is concerned, this cannot be accepted, as this is a violation of the constitution and of criminal procedure.” The Serbian legal system did not permit any foreign intervention in domestic affairs, it was argued. The very same day, Vienna broke off its diplomatic relations with Serbia, and on 28 July, the Austro-Hungarian emperor declared war on Serbia. It was the culmination of a looming crisis long in the making.

War, Retreat, and Occupation

The Austrians harbored the illusion that the war would be short and therefore sent an underfinanced, poorly equipped, and rather unmotivated army into battle against Serbia. As a precautionary measure, martial law was declared already on 25 July in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Dalmatia, pro-Yugoslav newspapers were banned, and opposition leaders and “Serbian spies” were arrested, deported, or executed on a massive scale. Vienna made preparations to repress the predictable wave of solidarity with Serbia.

On 11 August, General Oskar Potiorek crossed the Drina from Bosnia-Herzegovina with three armies and headed into Serbia. Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes living under Habsburg rule were forced to fight; in some units they made up as much as 40 percent of the troops. One of them was the 21-year-old locksmith Josip Broz, later known as Tito. The area of eastern Bosnia and the Drina valley was one in which much of the fighting took place. It was from here that the Austrians advanced toward Serbia. Serb volunteers led by Kosta Todorović took the provincial city of Srebrenica on 18 September 1914 but were driven from there shortly afterward by the Austrians, who killed the commander and, together with Croat-Muslim legionnaires, committed hideous atrocities against the civilian population. In Serbian historical memory, Todorović became a hero and is still commemorated today. His story serves as an early parable in the national discourse on sacrifice.

The Austrians soon found themselves in difficulty because of poor strategic planning, logistic problems, and the highly motivated Serbian army under the command of the elderly Serbian general chief of staff Radomir Putnik. Although the Balkan wars had exhausted the Serbs, militarily they were well trained and psychologically hardened for war. On the plateau of the mountain Cer, where the Drina and Kolubara rivers converge, they pulverized Potiorek’s soldiers. Nearly 274,000 Austrian troops were killed in the first year of the war. By the end of 1914, the Austro-Hungarian troops were trapped in the Balkans, the war virtually lost. The Serbs commemorate the important battle with the patriotic song “March on the Drina,” which praises their soldiers’ bravery and love of liberty.

The brutality and totality of the war in the Balkans was characteristic of the conflict from its very beginning in the summer of 1914 and not just the result of the escalating dynamics of violence. The Austrians were convinced that the Serbs would conduct a bloody guerrilla war with the help of irregular fighters, the komitadži. Invoking “Kriegsnotwehrrecht,” the wartime right to self-defense, the Habsburg troops committed horrific devastation and mass atrocities that stood in clear violation to valid international laws of war and appalled foreign observers. A “Direktion für das Verhalten gegenüber der Bevölkerung in Serbien” (directorate for the behavior toward the population in Serbia) ordered: “The war leads us into an enemy country that is inhabited by a population filled with fanatical hatred toward us. Any form of humanity or tenderheartedness shown to such a people is not only misplaced but actually baneful, because such deference, which in wartime is otherwise possible now and then, would in this case seriously endanger the security of our own troops.” The Austro-Hungarian armies took civilians as hostages; killed thousands of men, women, and children “in reprisal” for partisan attacks; burned down villages; and plundered as much as they could carry. This was the case not only in Serbia but also on the other side of the Drina in Bosnia-Herzegovina. “ ‘Our troops,’ one soldier serving with the Honved reported, ‘have struck out terribly in all directions, like the Swedes in the Thirty Years War. Nothing, or almost nothing, is intact. In every house individuals are to be seen searching for things that are still usable.’”

Rudolf Archibald Reiss, Professor for Criminalistics and Forensics in Lausanne, traveled to the Serbian front in 1914 and documented the horror for the rest of the world. Innumerable cities and villages were described as consisting only of ruins, such as Šabac: “Go into any house … everything is empty and plundered. Everything that could not be carried away was kaput, broken or in some way made unusable.” Wherever the Austrians moved in, men were viciously slaughtered, women raped, entire settlements destroyed beyond recognition. On 30 July they arrived in the village of Prnjavor and assembled all the local men. Any man on whom they found a conscription order or even just a bullet was immediately shot. The 60-year-old Jovan Maletić, who witnessed the butchery along with forty hostages, described what he had seen:

By the time the Swabians [a commonly used name for Austrians] brought by the 109 inhabitants from Prnjavor, the soldiers had already dug the grave. They tied them together with rope and wrapped the entire group with barbed wire. Then the soldiers positioned themselves on the railway embankment about 15 meters [50 ft] away from the victims and fired off a round. The entire group tumbled into the grave, and other soldiers shoveled dirt over them without checking if all were dead or if there were still wounded among them. Certainly there were many who had not been fatally wounded, at least a few, but the others had pulled them all down into the grave. They were buried alive!

“Anyone who has seen all that I have seen,” wrote Reiss, a native of Freiburg, “will never be able to forgive.”

Serbia had successfully contended its victory at an enormous loss of human lives and property. The hardship suffered by the country at the outbreak of the war defied description. Soldiers and refugees in the hundreds of thousands and war prisoners in the tens of thousands needed to be provided for. But the economy had come practically to a standstill. In the first war year alone, 163,557 of the 250,000 soldiers and another 69,000 civilians died. Nearly 600,000 refugees were on the move. In early 1915, a typhus epidemic broke out. International aid workers counted 400,000 sick and 100,000 dead. The catastrophe was not contained until five months later.

In the meantime, Austria-Hungary was preparing a counteroffensive. This time the Central Powers were better prepared and had pulled Bulgaria to their side. In October 1915, ten German divisions crossed the Danube from the north, while the Bulgarians invaded from the east. In order to save his army from annihilation, General Putnik ordered a retreat on 26 November 1915, over the mountains to the Albanian coast. The High Command, the elderly King Peter, and numerous members of the government, members of parliament, and intellectuals joined them. It was announced that Serbia would not surrender at any price, despite the superiority of the enemy forces. The men, women, and children left behind were armed.

The formerly proud Serbian army degenerated into a demoralized and internally dissolving force. Many soldiers simply went home. Only those who did not take to their heels started the long trek to the coast. Marching over hazardous paths, the starving, freezing, and deathly exhausted men fought their way through snow and ice at temperatures falling to –4oF/–20oC. “Slowly we crawl up the bare cliffs on the slopes of the Čakor. Step for step on the downtrodden snow we move forward,” wrote Josip Jeras in his diary. “On the sides of the path, exhausted refugees, trapped in the snow, their heads lowered. White snowflakes dance around them, and the mountain winds whistle the funeral dirge. The heads of fallen horses and oxen jut out of the snow.” Caravans of civilian refugees followed the troops: “There were no houses by the way, no refuge of any kind. … If anyone became exhausted, what could be done? … The other members of the family were powerless. It was a case of the rest of the family pushing ahead or of all perishing together,” reported British rear admiral Ernest Troubridge, who accompanied the wretched trek. The horrible, grueling march is often referred to as the Albanian Golgotha. It took the lives of about 150,000 and left another 77,000 missing. Only 140,000 people made it to the Adriatic coast; from there the starved and ragged survivors were shipped to Corfu and Thessaloniki by the Triple Entente. By the spring of 1916, Serbian troops were once again fighting on the frontlines, this time on foreign soil near Thessaloniki.

The victors—Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Bulgaria—were convinced that Serbia had to disappear from the map as a political entity. However, there were differences of opinion on how to go about this. Should the entire country be annexed or should Serbia be extremely reduced to no more than an economically dependent rump state? At first they divided the country among themselves and set up a harsh occupational regime in the fall of 1915.

The objectives and practices of the occupation amounted to no more than the ruthless denationalization and plundering of the occupied regions, meant to ensure that the state of Serbia would vanish for good. The Austrians set up the Military Governorate of Serbia and introduced a rigid economic system of exploitation. In addition, political organizations and societies were forbidden, and schools were brought under their control. In March 1916, General Conrad ordered that all resistance be destroyed with ruthless severity, that the country be squeezed dry, and that no mercy be shown for the hardship this caused to the general population. Harvest yields and produced goods had to be turned over to authorities; food was rationed. Officials interned 16,500 men fit to bear arms until November 1916. That winter, starvation killed more than 8,000 Serbs, according to Red Cross reports, while figures from the Habsburg High Command reported that 170,000 cattle, 190,000 sheep, and 50,000 pigs had been requisitioned and exported to Austria-Hungary by mid-May 1917.

In late September 1916, the Serbian High Command flew in the guerrilla leader Kosta Milovanović Pećanac from Thessaloniki to organize resistance in Serbia. In February 1917, a force of 4,000 armed men and women managed to liberate an area in the Morava valley, but then the uprising was put down. The Austro-Hungarian military reported 20,000 dead and the escape of 2,600 into the forests.

Starting in November 1915, the Bulgarians established themselves in the eastern part of the country, where they had an old score to settle with Serbia. In 1912/1913, Serbia had ruthlessly “Serbianized” territories annexed from Bulgaria. The churches and schools of the Bulgarian Exarchate had been closed, Bulgarian newspapers banned, Greek and Bulgarian names translated into Serbian ones. When power changed hands at the end of October 1915, the situation reversed itself, and the Bulgarian military government in eastern Serbia, Macedonia, and parts of Kosovo began an unrelenting process of Bulgarianization, occupation, and economical exploitation.

Particularly hard hit were the Serbs. All former soldiers between the ages of 18 and 50, as well as teachers, doctors, journalists, civil servants, and other officials were interned, shot, or transported to Bulgaria as prisoners of war. Another 46,000 or so were deported there as forced laborers. Serb names, alphabet, and language were forbidden; books and maps were banned from the public. However, the occupiers did not treat the Muslims significantly better.

Whereas Austria-Hungary conducted the war against Serbia out of its existential interests, Germany was pursuing primarily economic aims. Berlin took charge of exploiting the mines, controlling the railway in the Morava valley, and organizing a swath of territory behind the lines (Etappenzone) used to provision its troops on the Salonica Front. Germany incorporated Serbia into its planning of the war economy, since the Germans were experiencing acute deficits in raw material and food as a result of the British trade blockade. To handle the exploitation of occupied Serbia, the Deutsch-orientalische Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society) was created, based on the model of other German organizations working elsewhere to secure the supply of raw materials needed for the war. This exploitation drove Serbia so deeply into destitution that even Austrian representatives in Berlin filed complaints. Likewise in Bulgaria, the Germans had forced Sofia to let the War Raw Materials Department of the German Empire manage the mining of iron ore, so necessary for steel production.

The Salonica Front ran across all of Macedonia. It was a broad band of destruction, 80 to 95 miles long, that was repeatedly ploughed up by the artillery on both sides. By mid-1916, the fighting had reached such a stalemate that a crisis in provisioning the civilian population and the military reached catastrophic proportions. More and more of the Central Powers’ soldiers, including many Bulgarians, refused to take orders, deserted, or defected to the other side.

Two years later, on 15 September 1918, the Serbian army launched a major offensive that finally broke through the front lines. Accompanied by its allies, it marched in the direction of the Danube and liberated Belgrade on 1 November. From the outbreak of the Balkan wars in 1912 to the armistice in 1918, Serbia, Macedonia, and Kosovo had suffered almost unceasingly from extreme violence, hunger, and disease. These experiences brought about deep-seated material, societal, political, and sociocultural transformations.

Of all the countries involved in the First World War, Serbia had suffered the greatest loss of life with 1.2 million war dead by the end of the conflict. Fifty-three percent of the male population between 18 and 55 had been killed, and 264,000 were invalids. Almost all livestock had been either destroyed or requisitioned. For the Austro-Hungarian South Slavs, the experience of war had proven to be a decisive one. Part of the Isonzo Front ran across Slovenian soil, which resulted in tens of thousands of Slovenes being exiled or deported to Italy, Austria, and Hungary. Nearly 300,000 Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, and Slovenes had lost their lives as frontline soldiers fighting on behalf of foreign powers.

Millions of people had gone through life-threatening experiences, been forced to flee their homelands, and lost relatives and property. This unraveled the old social order. As long as the men, at one point more than 700,000 of them, were off fighting, traditional gender roles had to be redefined. During the war years, women took the place of men as the head of households, performed extremely hard labor for months at a time for the occupation forces, fought in the resistance, and lived a more liberal sexual morality.

In exile on Corfu, where political life continued, the 26-year-old Serbian prince regent used the emergency situation to deal with the secret organization Black Hand, which was allegedly hatching plans for an overthrow in its aim to create a Greater Serbia or Serb-dominated Yugoslavia. In 1917, ten officers were tried for high treason in Thessaloniki, and their leader, Apis, was executed along with two co-conspirators. This ended the rivalry that had existed since 1903 between military and civilian institutions of power and enabled the Serbian state to further consolidate itself.

The trail of destruction and destitution left by the war, the years of trauma, and the massive loss of human life left the entire South Slavic region with a pressing need to justify and attribute meaning to the sacrifice rendered. The prospect of national resurrection and greatness fulfilled this need in Serbian public opinion. Historians, politicians, and intellectuals knew how to incorporate the experiences into the public culture of remembrance. They heroized, sacralized, and mythologized the history of the war by stylizing the Serbs as a nation of martyrs and victims in the monuments they erected and the veteran cult they created. To cultivate this war culture as a common framework of reference and orientation meant to create of a new understanding of national community and political legitimacy, one in which the war ascended to become the founding myth of the new Yugoslav state.