From a military point of view, one can relate to the castle – any castle – as a complex and expensive technological development intended to with- stand attack and to ward off enemy attempts to capture or mount a siege against it. Castle architecture, like all other improvements in military technology, was influenced and shaped by a constant tactical and strategic dialogue between opposing forces. When one side developed a new and successful siege tactic, the opponent countered with a new strategy of fortification that took the edge off the enemy’s innovation. This in turn led the attacker to come up with a new strategy for besieging the castle, and the cycle was repeated.

This phenomenon led Hugh Kennedy to write: `The development of castle architecture must be seen as the result of continuing dialectic between attack and defence which gave the advantage sometimes to one, sometimes to the other. Only by examining techniques of attack can we come to a real understanding of the architecture of defence.’ In other words, Frankish military architecture reflected not only the construction methods with which the Franks were familiar, but also Muslim tactics of siege and warfare, as well as the financial ability of the owners of these strongholds. And yet, even in his brilliant and innovative analysis of the strategic dialectic between the Frankish castle and Muslim siege tactics, Kennedy hardly refers to the gradual development of this very dialogue over time and space. He adopts a generalised approach to the common siege techniques and defence tactics, providing examples for every type of warfare and all types of fortifications, but the exact cause and effect relationship between new attack techniques and new defence tactics remains rather cloudy.

And yet, even if my assertion is correct, and the Franks were not endangered by the external enemies throughout the entire period and in all of their territory, they nonetheless had to strengthen their fortifications in accordance with the changing threats. It can be suggested, therefore, that to the extent to which a castle was subject to greater and more frequent threats, the greater was the tendency to invest more resources in the improvement of the fortifications. The opposite argument is also logical: to the extent that the threat was less imminent, the settlers could make do with less expensive and more compact fortifications.

The underlying assumption of this approach is that only an understanding of the ongoing development of the tactics of siege warfare of both sides and a better understanding of the ever-changing balance of power can enable us to gain a clear picture of the ongoing development of defence techniques. Siege warfare and castles account for only one part – important as it may be – of medieval military strategy, and it is impossible to separate the siege and defence tactics from the other elements of their military techniques. Besieging an individual castle is generally only one component of a wider plan of attack which always includes advancing into enemy territory and deploying siege machines, and on the other hand the advance of reinforcements and supplies to the besieged castle. This chain of events might end with the surrender of the besieged castle, the retreat of the besieging armies, or a general showdown in a field of battle.

Thus, the transformations undergone by the Frankish castles cannot be explained solely on the basis of their architectural features (as many of Kennedy’s predecessors attempted to do). However, these architectural changes also cannot be explained simply through a generalised analysis of techniques typical of warfare between Muslims and Crusaders, for these were not the only components of the strategic dialectic between them. The superiority or inferiority of one of the field armies is as important as the financial capabilities of the landlords and their willingness to invest the huge sums needed to provide defence and fortifications.

As for the balance of power between Frankish and Muslim land forces, it is reasonable to assume that during periods of clear Frankish superiority in the field there was less of a threat to nearby Crusader castles. During these periods the Muslims were fearful of engaging in direct land battles and were quick to lift the siege and flee when Frankish reinforcements drew near. The average duration of a Muslim siege during such periods was five or, at most, ten days, the length of time it took Frankish forces to come to the rescue of the besieged castles. The Frankish castles built during such periods were planned so that they could hold out for a week. A longer period of time was unnecessary and there was no need to invest huge sums in mighty fortifications or immense supplies of water and food.

In periods and regions in which the opposing land forces were more or less of equal strength, or during periods in which the Muslim armies were more formidable than those of the Franks, the frequency of Muslim sieges increased, as did their potential length. The castles erected in the frontier areas of the kingdom from the 1160s onwards were planned to withstand lengthier sieges and more frequent attacks than those of the earlier period, because the defenders within their walls could not rely on speedy relief by reinforcements from the centre of the kingdom.

We may conclude, then, that the strength of the castles and the sums needed to erect and equip them were in inverse ratio to the might of the land forces in the immediate vicinity: in periods and areas in which the Franks held military superiority they could make do with smaller, less fortified castles; whenever and wherever the Muslims held the upper hand, the Franks were in need of more mightily fortified castles.

Several factors influenced the relative cost of incorporating defence technologies. The stronger the Muslim land forces and the more improved their siege techniques, the longer the potential duration of the siege they could mount and the mightier the Frankish castles became. Therefore, the cost of castle building increased in a direct ratio to their potential of being besieged and the potential length of the siege warfare. Not every lord was able to assemble the funds needed to fortify and equip his castle; moreover, even if he were able to come up with such sums, it is doubtful that he would expend them unless conditions made this absolutely necessary. It is therefore quite likely that the new and expensive technologies were implemented differentially throughout the kingdom, depending on the frequency of the Muslim attacks and their geographic diffusion. More sophisticated strongholds were first erected in regions more prone to attack or those which in time became frontier areas; only later did these innovations also seep down into other regions in the interior of the kingdom. As a result of these high costs, in the final tally the frontier castles were gradually transferred from the possession of their seigneurial lords to the military orders, which could more easily raise the necessary funding.

Thus, I maintain that study of the archaeology and military architecture are not enough to gain an understanding of their development. Technological innovations and the speed of their diffusion, financial ability, and differential capabilities of the opposing land forces were important considerations influencing military architecture. Moreover, it is not enough to point to the dialectic between Muslim attacks and Frankish defence, for there was a simultaneous, ongoing dialogue by both sides concerning the adopted technique in both siege-fare and defence. I shall attempt to trace, in as great detail as possible, the sieges mounted by both Franks and Muslims, and try to ascertain the relative advantages of each side in the conflict. This analysis will enable us at a later stage to better understand the significance of Frankish military architecture.

Frankish Siege Machinery and Logistics During the First Crusade

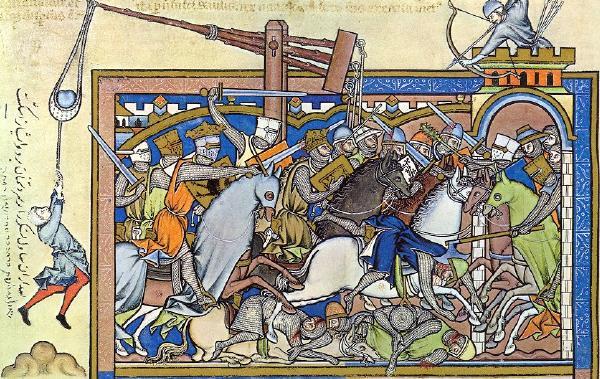

The siege and defence tactics employed by the Franks during the First Crusade, and also later, when they took the cities along the Mediterranean seashore, were different from those used by the Muslims during that same period. Frankish attacks were almost always supported by siege engines and siege towers, as well as by various types of artillery, whereas the Muslims did not erect towers and made little use of heavy artillery when besieging enemy castles. They preferred tactics which became traditional: direct storming of the castle, a tight blockade, tunnelling under the walls, and limited use of light artillery.

The difference between the siege tactics of the two warring camps apparently did not stem from poorer technological skills of the Muslims; Latin chroniclers specifically mention that the Muslims were acquainted with heavy artillery and even employed it in defence. But the use by the Franks of heavy artillery, and especially of siege towers, was much more frequent. In fact, it can be maintained that they employed both these means in almost every siege they mounted, while the Muslims did so only very rarely.

I believe that the difference between the siege tactics can be put down to the Franks’ superior logistic capabilities during the first quarter of the twelfth century. They had advanced transport facilities, including four- wheeled wagons; they could call upon the services of trained craftsmen and carpenters who served in their land forces or supporting fleets; and they could count on ships for transport and much logistic support. The Muslim armies too employed the services of Muslim sailors, but they did this more to enhance their defence than their attack abilities. The Frankish superiority in logistic capabilities already came to bear during the First Crusade. The Franks began the siege of Nicaea, the first massive one mounted by the Crusaders in Asia Minor, with a tight land blockade, but what actually accounted for their victory was their superior technology and engineering, and the despair of the besieged.

Descriptions of the siege of Nicaea by Latin and Greek chroniclers indicate just how much the balance of power between the Frankish and Muslim land forces influenced the morale of those within the city. At first, when the Nicaeans believed that no outside help would be forthcoming, they agreed to surrender to the Byzantine emperor. Somewhat later, when they learned that the Seljuk sultan had not abandoned them and was trying to come to their aid, they were more determined and decided not to surrender, but to fight on.

The Franks then erected siege engines and positioned various types of artillery. Most of the engines were intended to protect the soldiers who were digging under the city walls to weaken their foundations, but Anna Comnena relates that her father, Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus, who had little faith in the Crusaders’ ability to take the city, suggested that they use a new type of artillery. Anna does not provide specific details about this weapon, but she does note that the Franks did employ, inter alia, a rock-propelling device known as Helepoleis. The Helepoleis was already known by this name during classical antiquity, and Paul Chevedden, who has studied the development of medieval artillery for many years, believes that `Helepoleis’ does not necessarily signify a specific weapon; rather it is used to designate the most advanced type of artillery existing during each specific period of time. Chevedden provides no proof to substantiate this argument, but he bases his assertion upon it and on the fact that Anna Comnena mentions a new type of weapon, concluding that during the siege of Nicaea the Byzantines for the first time supplied the Franks with an artillery piece of the counterweight trebuchet type, which replaced earlier sorts of artillery (each of which had in turn been called Helepoleis). Though Chevedden’s articles are based on a multitude of references, I have been unable to find in them support for the argument that `Helepoleis’ designated the most advanced type of artillery at a certain point in time, or that the counterweight trebuchet was already in use at the time of the siege of Nicaea. Rogers and France too, both of whom have studied the Frankish siege of Nicaea, did not find any evidence of this fact in the sources describing that event. The question is too vast to be dealt with here in full, but it should be noted that the majority of the students of Frankish and medieval Muslim artillery follow Huuri, in asserting that leverage artillery was invented in China and was brought to the East and from there to Europe, but most of them date the invention of the counterweight trebuchets to the twelfth century.

Nonetheless, even if the Franks did not have artillery of the counter- weight trebuchet type at their disposal when they besieged Nicaea, they were able to employ other relatively advanced types of artillery, at least some of which had been planned and built by Frankish craftsmen on the basis of knowledge they brought with them from their countries of origin. The Latin sources repeatedly mention, sometimes even by name, crafts- men and carpenters who were an inseparable element of the fighting force. They also note that craftsmen were hired and paid to perform professional tasks, some of them even losing their lives while engaged in construction efforts. For example, two German noblemen, Henry of Aische and Count Hartmund, funded the construction of a mobile roof of oak planks to protect twenty knights who were digging under the city walls. This stratagem failed, however, and the roof collapsed under the weight of the rocks hurled down by the defenders. Some time later, craftsmen from southern France in the entourages of the count of Toulouse and the bishop of Le Puy were hired to erect a very high tower along Nicaea’s southern wall. The warriors atop this tower successfully created a breach in the wall, but the defenders soon blocked it.