Gwalior Campaign (1843) In 1843, the East India Company was concerned about the turbulence and intrigue surrounding the succession and rule of an adopted child-heir in Gwalior, the stability of that state, and the potential threat of the Gwalior military to the British. There was apprehension that the Maratha resistance against company rule could be renewed, and it was reported that the dissidents in Gwalior were secretly seeking support from the Sikhs and other princely states. After the British humiliations in Kabul and at the Khyber Pass during the First Afghan War, the company’s military reputation and credibility needed bolstering. The governor-general, Lord Ellenborough, attempted to discuss the situation with the Gwalior council of regency, but when he was rebuffed, company forces attacked Gwalior to suppress its military force.

Company armies were assembled at Agra, under the commander in chief, Lieutenant General (later Field Marshal Viscount) Sir Hugh Gough, and at Jhansi, commanded by Major General John Grey. The two forces, beginning their march on 17 December 1843, were to converge on Gwalior, Gough’s from the north and Grey’s from the south.

The Mahratta Army of Gwalior established strong defensive positions at Chonda on the Asun River. Due to the difficult terrain, Gough’s force was divided into three columns. He intended to turn the enemy’s left flank with his cavalry and infantry, threaten the enemy’s left flank , with the main attack being a frontal assault.

Reportedly with no scouts in advance, Gough’s force m arched out of its assembly area early on 29 December 1843 and arrived at the village of Maharajpore. The Mahrattas had established new positions at this advance location, and this forced Gough to change his plan. What appeared to have been a flat plain between the forces was in fact ground devoid of cover and full of ravines. Th is made it impossible for the infantry, cavalry, and artillery to coordinate their actions, and when Gough’s force came with in 1,500 yards of the village, the well-trained Mahratta artillery opened up a murderous fire. Gough’s response was simply, “On and at them!” (Featherstone 1992, p. 33).

Gough’s three infantry and two cavalry brigades, totaling about 6,500 soldiers with 30 field guns, attacked the 17,000 Mahrattas. Amid the smoke, confusion, bad terrain, and fierce fighting, the British force was finally able to overcome its adversary. The British loss es totaled 797 all ranks killed, wounded, or missing. The Mahrattas suffered over 3,000 men killed and wounded and lost 56 guns. Gough admitted to underestimating his foe. The Battle of Maharajpore was a ‘soldiers victory’ won by the bayonet without the benefit of tactics, strategy or manoeuvring. Gough displayed no generalship whatsoever and gave but one order” (Featherstone 1973, p. 50).

On the same day, 29 December 1843, Grey’s force reached the village of Punniar, about 12 miles south of the Gwalior Fortress. A Mahratta force suddenly attacked Grey’s long bag- gage train. He sent half his horse artillery and a cavalry element to the rear of his column, and this saved the baggage.

In the afternoon, Grey’s force was threatened by 12,000 Mahrattas positioned on high hills to the east. Grey ordered the 3rd Foot and sappers and miners to conduct a frontal assault, while the 39th Native Infantry attacked the Mahratta left flank. The 3rd Foot’s determined assault was successful, and it drove the Mahrattas from their positions and captured 11 guns. At the same time, the 39th Native Infantry seized a hill that dominated the Mahratta position. After numerous volleys, the 39th rushed to the Mahratta positions and captured 2 guns, while the 2nd Brigade, which had been held in reserve by Grey, attacked and shattered the enemy right flank, capturing 11 more guns. The entire British force then advanced against the crumbling Mahratta defenses. The Mahrattas fled the field, abandoning their 16 remaining guns and more than 1,000 casualties. British total casualties at the Battle of Punniar were 217 all ranks and 11 horses.

These two decisive victories ended the short Gwalior campaign, and the Gwalior regency capitulated. Gough’s and Grey’s forces linked up at Gwalior a few days later, and on 31 December 1843 a treaty was signed that reduced the Mahratta Army, established a British resident in the capital, and provided for the British occupation of the Gwalior Fortress.

Edward Armitage (1817-96) The Battle of Meanee, 17 February 1843

The Passage of the River Chumbal by the British Indian Army’. . London, c.1850. Lithograph by Dickinson & Co. after Capt. Charles Becher Young. India. Military. Source: P801.

British Uniforms

The year following the conclusion of the Afghan War saw two further campaigns in India: the Conquest of Scinde and the very brief Gwalior Campaign against the Mahranas, sometimes known as ‘The 48 Hours War’. Sir Charles Napier conquered the Balucltis of Scinde with a force containing only one British infantry regiment, the 22nd, which distinguished itself at the Battles of Meanee and Hyderabad on 17 February and 24 March 1843 respectively. The regiment is shown at Meanee in a large painting exhibited in 1847 by Edward Armitage RA, reproduced herewith. Armitage was not primarily a battle painter but his military subjects are executed with precision, and for this painting he acquired material through the help of Napier’s brother, William. The 22nd’s officers are in uncovered forage caps and either frock coats or shells, while the men wear their dress coatees and locally-made blue-grey trousers. Their peaked forage caps, probably of the ‘pork-pic’ type, have white covers and curtains.

Paintings of Meanee and Hyderabad (sometimes called Dubba) were executed by GeorgeJones RA, advised by Napier’s officers. Napier preferred Jones’s rendering of the action to Armitage’s, but his style was less attentive to costume detail and his Meanee painting shows the 22nd in coatees but with winter trousers and white-covered shakos with curtains. However, his Hyderabad painting depicts similar dress to Armitage, so possibly the conflicting headdress and trousers resulted from misinterpretation of information he received. The latter painting also includes a troop of Bombay Horse Artillery in its full dress; its helmets had black manes and a brush on the front of the crest, whereas those of Bengal and Madras had red manes and no brush.

In Scinde Napier used 350 men of the 22nd as camel-mounted infantry in pairs for his expedition to the desert stronghold of Imamgarh.

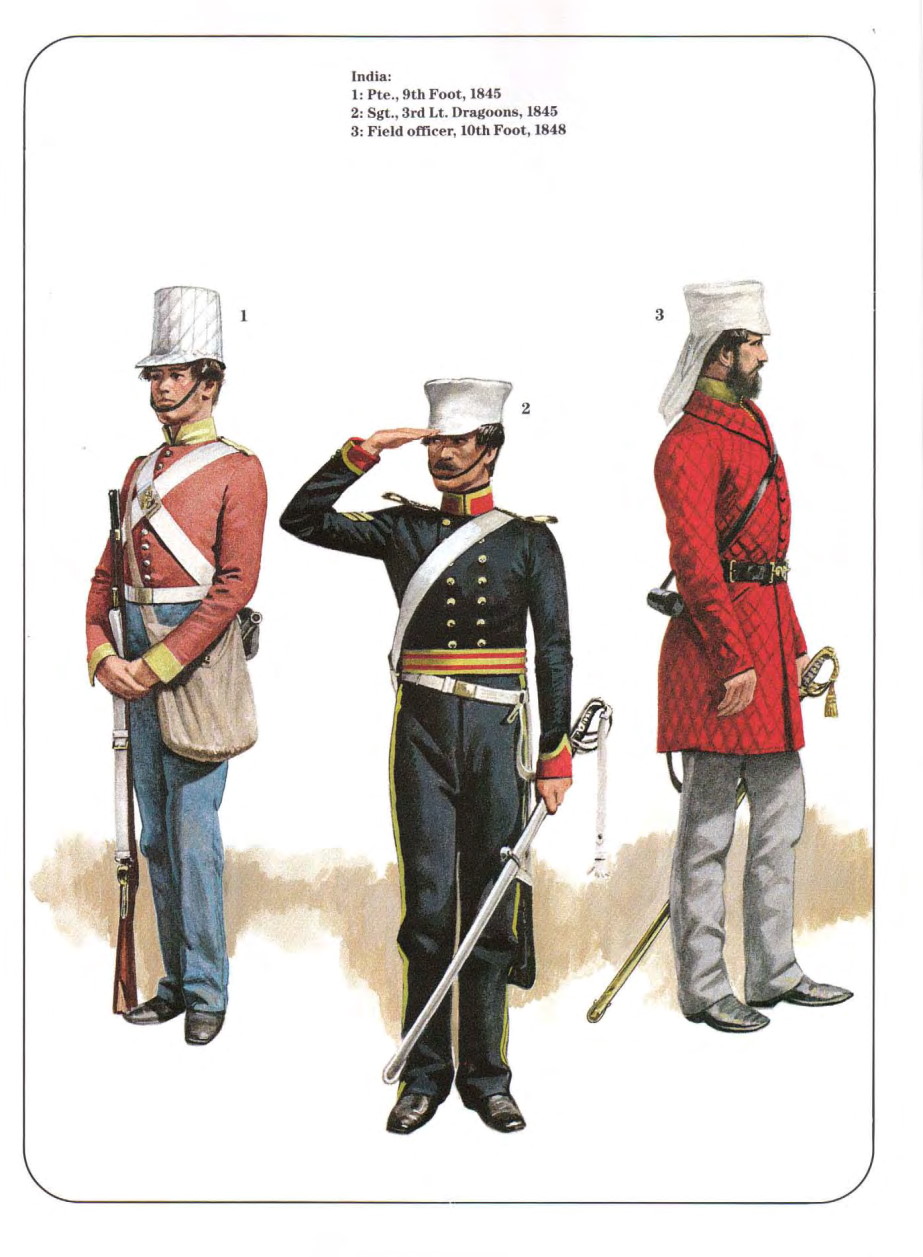

Two battles, Punniar and Maharajpore, were fought on the same day-29 December 1843-in Gwalior. A lithograph after Capt. Young, Bengal Engineers, of troops crossing the River Chumbal before Punniar has a small figure, probably of the 9th Lancers, all in dark blue and white-covered lance-cap. At this date the 9th wore a wide waist belt, similar to the Heavy Cavalry’s, instead of the girdle. At least one officer of the 39th Foot fought at Maharajpore in a shell jacket, for the garment in which Ensign Bray was killed is preserved, together with his forage cap and colour belt, in the Dorset Military Museum. Tn the same museum is an unsigned watercolour entitled ‘European troops halting’. From the green-faced shells, the ’39’ marked on a pouch and a haversack, and from the fact that the 39th left India soon after Maharajpore, it must depict that regiment in the Gwalior Campaign. The style resembles the work of” an officer of Bengal Native Infantry, B. D. Grant, whose other drawings will be met later. All the forage caps have white covers, but while most must be of the ‘pork-pie’ type, two are of the former broad-crowned pattern. Their pale blue-grey trousers must be locally made. In addition to their cross belts, the men have haversacks and the narrow waist belt described earlier. They are armed with the new percussion musket and have a small black pouch, containing the caps for this weapon, attached to the waist belt to the right of the clasp.

The appearance of a complete British regiment in India at this period is shown in a panorama titled Line of March of one of H. M. Regiments in Guzerat, drawn in 1845 by Lt. Steevens, 28th Foot, which was employed on the periphery of the Scinde Campaign. This shows the regiment in shelljackets, bright blue trousers, and forage caps annotated by the artist: ‘The forage cap is covered with quilted cotton, with a curtain hanging down behind, as a protection from the sun’. The men are accoutered as described for the 39th but without waist belts.