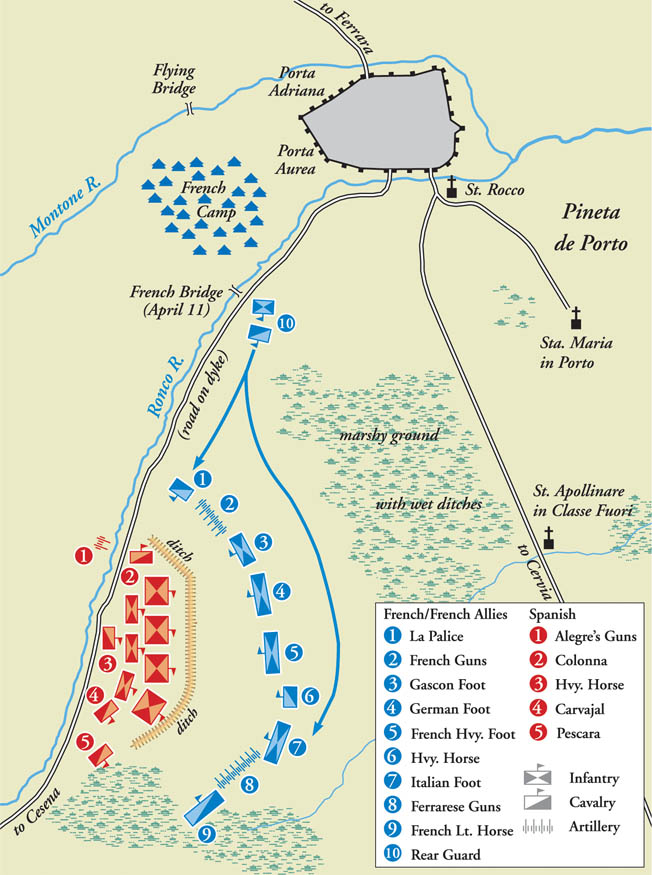

Battle was joined on 11 April, Easter Sunday – from that very day, it was seen as an epic encounter. The Spanish and papal army took up a position south of Ravenna on the right bank of the river Ronco; the high embankments of the river were broad enough for large numbers of horse or foot to pass along them easily. Starting at right angles to the river, they dug a long, curving trench, leaving a gap at the river end. Their artillery was positioned at that end of the trench. The other units were drawn up in file, not to defend the line of the trench; the men-at-arms were nearest the river, the infantry in the centre and the light horse on the right wing. Pedro Navarro, who commanded the infantry, had placed in front of them about 50 light carts with projecting blades, protected by arquebuses. The French crossed the river near the city by a bridge de Foix had had built; d’Alegre was left with the rearguard to protect this. They took up position along the trench, the men-at-arms nearest the riverbank, with artillery placed before them, separate units of German, French and Italian infantry side by side, and to the left the light horse and archers.

The Spanish and papal troops were outnumbered and they knew it: they had about 20,000 men, while the French had 30,000 or more. 102 Cardona had put 1,500 men under Marcantonio Colonna into Ravenna, and much of the papal army was not there, because the Duke of Urbino refused to be under the orders of the viceroy. Alfonso d’Este with 100 men-at-arms and 200 light horse was with the French. More significantly, he had brought his renowned artillery, giving the French perhaps twice as many artillery pieces as the League. Besides the guns positioned opposite the Spanish artillery, a couple of pieces were placed on the other side of the river, and d’Este with his artillery at the far end of the French line.

The battle began with an artillery exchange, unprecedented in its length – over two hours – and its ferocity. The Spanish guns were aimed at the infantry, causing significant casualties; the League’s infantry were instructed by Navarro to move to a place where they could lie flat and evade the French and Ferrarese artillery. But there was no escape for their cavalry, who were caught in the crossfire. Eventually, the Spanish heavy cavalry were driven to leave their defensive position and attack the French men-at-arms. As they were trying to silence the Ferrarese guns, the Spanish light horse under the marchese di Pescara were attacked by the French light horse.

In the engagement between the French and Spanish men-at-arms, the Spanish were less disciplined and coordinated. D’Alegre and his rearguard joined the fight and turned the scales against the Spanish. Their rearguard under Alonso Carvajal broke and fled the field; Cardona left with them. Meanwhile the French infantry crossed the trench to attack the League’s infantry, taking heavy casualties from the arquebuses as they tried to break through the barrier of the carts. The Gascons were put to flight along the riverbank. As the Spanish infantry units and the landsknechts of the French army were locked in fierce combat, the French cavalry, having overcome the Spanish, were able to come to the aid of their foot. Fabrizio Colonna rallied what men-at-arms he could to defend the League infantry, but could not prevent their defeat. Although 3,000 Spanish infantry were able to retire in good order along the river bank, the rest were killed, captured or dispersed.

By mid-afternoon the hard-fought battle was over. Contemporaries, appalled at the scale of the slaughter, considered it to be the bloodiest fought on Italian soil for centuries. It was estimated that upwards of 10,000 men were killed; some put the total as high as 20,000. There were disagreements about which army had suffered the greater mortality. It was probably the League, whose losses may have been three times those of the French. In one significant respect, the French losses were greater – among the commanders. While the Spanish lost some experienced and valued captains, the more prominent were captured rather than killed, including Pedro Navarro, Fabrizio Colonna and Ferrante Francesco d’Avalos, marchese di Pescara; the papal legate, Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, was also taken prisoner after the battle. French losses among their commanders and nobles were heavy. Among the fallen were Gaston de Foix, apparently killed by Spanish infantry, Yves d’Alegre and his son, Soffrey Alleman, seigneur de Mollart, the captain of the Gascon infantry, and Philip of Fribourg and Jacob Empser, captains of the landsknechts.

For the French, the death of de Foix cast the greatest shadow over their victory. If his bravery had bordered on the foolhardy, in his brief period as commander of the army he had shown himself an inspiring leader, always in the thick of the action. Cardona, by contrast, seems to have left leadership to his subordinate commanders; he was widely blamed for their defeat. `In truth, he knows nothing of warfare’, was the verdict of Vich, Ferdinand’s ambassador in Rome, `and everyone complains that he never asks for advice or comes to a decision.’ Others have judged the outcome of the battle the result of the devastating effect of Alfonso d’Este’s deploy- ment of his artillery: `the true cause of the French victory’, according to Pieri. The French themselves were more critical of his role, for his guns had caused many casualties among them too, as he continued to fire once the troops were engaged.

The killing continued the following day, as the city of Ravenna, after an offer to capitulate had been made, was sacked by unrestrained Gascons and landsknechts who entered by a breach made in the walls by the earlier bombardment. Within a few days, nearly all the Romagna had surrendered to the French, only the fortresses holding out a little longer. This conquest was not due to any concerted effort by the French, for the weary troops were occupied in looking after their wounded and their booty from Ravenna. La Palisse, as the senior captain, had assumed command. He quarrelled with the Duke of Ferrara, who left the camp with his surviving men, some of the wounded and his prisoners, including Colonna and Pescara. News arrived that the English and Spanish had invaded France, that Maximilian had made a truce with Venice, and that the Swiss were again threatening Milan. Nevertheless, to save money, 4,600 infantry were dismissed.

La Palisse left for the Milanese on 20 April with over half the remaining troops. Cardinal Sanseverino, in his capacity of legate of Bologna for the schismatic council, and his brother Galeazzo, with 300 lances and 6,000 infantry, stayed to complete the conquest of the Romagna in the name of the council. When Louis’s orders – issued when he was unaware of the real state of affairs in Italy – arrived, they were for the army to press on to Rome. The army commanders decided the threat to Lombardy was more urgent.