Soon after London declared war on August 4, 1914, Britain’s colonial and dominion governments worked closely with the Admiralty to put together expeditions designed to seize Germany’s overseas ports and high-frequency radio stations. At the same time, the India Office organized the expedition to Mesopotamia to protect the Anglo-Persian oil fields. The choices political, military, and naval leaders made with respect to the overseas expeditions demonstrated that London’s decisions were foremost naval considerations. Whitehall’s priorities for overseas operations were, in order of importance, maintaining the integrity of the trade routes, eliminating logistics and intelligence bases for German commerce raiders, protecting an independent source of fuel for the Royal Navy, capturing and destroying Germany’s commerce raiders, and curtailing German trade.

TSINGTAO

Alfred William Meyer-Waldeck, the governor of Tsingtao, held the rank of captain in the German navy. He had 4,390 men available to defend the base there once he consolidated his available reserve forces. The defenders at Tsingtao consisted of about sixteen hundred marines from the III Seebatallion, plus a hodgepodge of other forces, including a contingent of Chinese colonial troops, naval personnel from four small German gunboats, and sailors from the Austro-Hungarian cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth. Several fortifications guarded Tsingtao, but the main defenses were oriented landward for an anticipated attack from technologically inferior Chinese forces. The gun emplacements held artillery that the Germans had acquired during the Boxer Rebellion in the early 1900s and from the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. The German East Asia squadron and mines nominally protected the base from attack by sea. Von Spee’s orders, however, indicated that the squadron’s first duty in a war with Great Britain was to inflict as much damage on British trade as possible. With the looming, combined Anglo-Japanese naval threat, Von Spee’s force risked becoming blockaded if it were in port when war broke out. As events unfolded, however, Germany’s East Asia squadron found itself widely dispersed on August 4, which made Tsingtao vulnerable to an amphibious landing.

Japan’s naval blockade rendered the port useless for German naval activity after August 27. On September 2, the Japanese landed a small detachment from the 18th Division at Lungkow, on the north side of the Shantung peninsula, to isolate Tsingtao from the mainland. On September 18, the Japanese began landing the bulk of their 18th Division at Laichow, in Lao-Shan Bay, about four miles northeast of Tsingtao. Delayed by weather, General Mitsuomi Kamio eventually built a force of 23,000 men that included a promised 1,500-strong British and Indian force—a combination of 925 to 1,000 soldiers of the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers and about 300 to 500 men of the 36th Sikhs—under the command of Brigadier General Nathaniel Walter Barnardiston. This mixed British-Indian force, although largely symbolic, likely constituted the first British force to fight under a non-European commander. Kamio’s plan called for a siege of Tsingtao supported with massed artillery consisting of 142 modern siege guns. Meyer-Waldeck held out for two months. Low on ammunition and artillery shells and greatly outnumbered, the governor surrendered on November 7. With the fall of Tsingtao, Germany’s powerful radio transmitter, the key link to the outpost at Yap, was also put out of service.

TOGOLAND

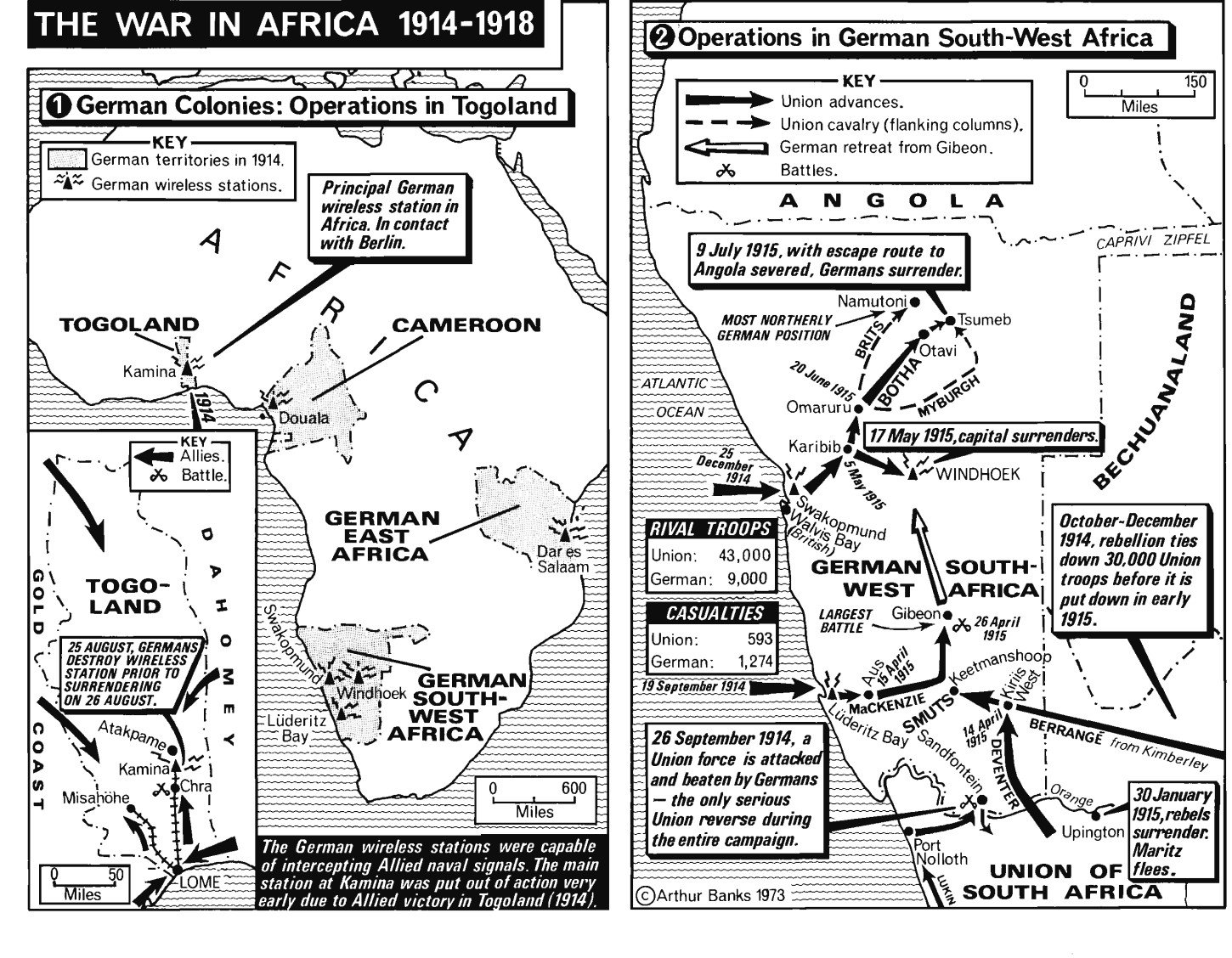

On August 6, Captain Frederick Carkeet Bryant, British army, found himself in acting command of the Gold Coast Regiment because the unit’s commanding officer and his deputy were both on extended leave in the United Kingdom. Bryant sent his subordinate Captain Edward Barker under a flag of truce to the Germans at Lomé, Togoland. Barker communicated the situation to the German authorities and demanded the town’s surrender. The government at Lomé did not immediately reply, but when Barker returned the following day, the Germans had abandoned the town. The district commissioner presented Barker a letter surrendering Lomé and all of Togoland inland for 120 miles.

The London Cable Telegraph Company had intercepted an unencrypted message from Togoland’s governor, Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg, to Berlin. The message indicated that the governor did not intend to surrender, but instead planned to withdraw from Lomé and prepare defenses inland, about 120 miles, at Kamina to protect the wireless station located there. The governor therefore surrendered Lomé immediately to avoid destruction of the city. Defending the wireless station at Kamina constituted the governor’s primary responsibility. London rejected the terms of the surrender because it would leave an important wireless station in operation to pass instructions and intelligence. Under the direction of the Colonial Office, Bryant proceeded to Kamina to seize the radio station.

On August 8, Major J. J. F. O’Shaughnessy, a telegraph engineer, arrived in Lomé with a team of technicians. The British team brought with them sufficient materials to establish and operate a temporary telegraph system. The Germans had dismantled a smaller wireless transmitter located at Lomé and transported it inland with them. O’Shaughnessy’s team located Germany’s submerged telegraph cable that connected Lomé with Monrovia and Duala, picked it up from the sea bed, cut it and sealed the ends. The operation severed German communications, but permitted the British to easily repair the cable or connect it to another line at a later time, demonstrating a technical capability that most other nations lacked.

Charles Noufflard, lieutenant governor at the French colony of Dahomey, corresponded by letter with the Gold Coast on August 8 to coordinate the two colonies’ offensives against Togoland. He reported that French troops had occupied Togoland in the vicinity of the Little Popo and Maro Rivers. One day later, British forces under Captain Barker were working directly with the French troops there. The governor general of French West Africa, Amédée Merlaud-Ponty, also volunteered his forces, offering to coordinate by invading Togoland from the north.

Captain Bryant received the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel so that he could outrank his French peers and command the military drive inland toward Kamina. The Allied forces overcame German opposition after a few battles. The Germans garrisoning the Kamina outpost destroyed the wireless station before surrendering to prevent the British from acquiring a working wireless transmitter. When German colonial troops, retreating from the final battle, arrived at Kamina, they found that the garrison had already completed demolition; all nine radio towers were down, and the building housing the diesel generator was burning.

Bryant reported on August 26, that all German forces in Togoland had unconditionally surrendered. British and French colonial forces occupied the site of the Kamina high-frequency radio station at 8:00 a.m. the following morning. Later that day at a meeting of the cabinet, Colonial Secretary Harcourt reported that the Togoland expedition had succeeded.

THE CAMEROONS

Early in the war, Britain, Belgium, and France decided on a combined operation against the Germany colony of the Cameroons. The plan called for two British forces to attack, one from the sea and one overland from Nigeria. The Belgians were to advance west from the Belgian Congo. Meanwhile, French forces from Chad and Congo would strike from their territories in the north and south, respectively. London proposed that British general Charles Dobell command the joint expedition. Francis Bertie, the British ambassador in Paris, assured the French that Dobell’s appointment would not prejudice the final disposition of the colony. The Foreign Office recommended leaving the choice of hoisting flags over captured German territory to the discretion of the field commanders. Secretary Grey attempted to push the Allies to agree that none of them would claim any German territory until the conclusion of a negotiated peace. In the opinion of the office’s ministers, having no policy in place was preferable to a policy to which the Allies might object.

German military personnel in the Cameroons numbered almost three thousand, but they were scattered widely among roughly forty separate outposts. The Cameroons defense plan called for the troops to delay Allied forces as long as possible while attempting to concentrate and escape into Spanish Guinea. This put a premium on preserving troops rather than retaining the colony. The Allied expedition against the Cameroons began following the German surrender in Togoland. British naval operations against Duala commenced on September 4, 1914. After about three weeks of fighting, the Germans destroyed Duala’s wireless transmitter and capitulated on September 27. Duala’s surrender did not, however, signal the end of the Cameroons campaign. As British forces advanced, the cabinet decided that the War Office would assume responsibility from the Colonial Office for the military operation. The Colonial Office presided over all other matters, including administrative appointments and trade. The War Office could not move colonial forces from Nigeria to support the campaign without prior Colonial Office approval. Fighting would continue until the last Germans surrendered at Mora on February 18, 1916.

Early in the campaign, British forces had captured two German ships in the harbor at Duala. One of them, Max Brock, had a cargo that Admiralty officials determined was neutral. The cargo was transferred to a British ship for delivery, thus emptying Max Brock. If the ship were condemned as a prize of war, the Colonial Office believed it could make use of the vessel. The Admiralty recommended that both captured ships, SS Max Brock and SS Kamerun, become transports that the Colonial Office could use for subsequent operations. Both ships were condemned and sold to British shipping firms.

GERMAN SOUTHWEST AFRICA

When South Africa learned of war with Germany on August 4, it volunteered to employ its dominion troops for self-defense so that regular British troops would be available for use elsewhere. On August 7, Whitehall suggested that South Africa seize parts of German Southwest Africa. London was particularly interested in the ports Luderitzbucht and Swakopmund as well as the wireless station in the interior. On August 10, the government of South Africa agreed to proceed with the expedition. The South Africans already had a plan for an offensive against the neighboring German colony, so preparation for the expedition moved rapidly. The plan’s author, General Paul Sanford Methuen, argued for an immediate offensive, reasoning that this would help the country put its internal disputes aside as well as deprive the Germany navy of its colonial ports. He also thought that a defensive posture would facilitate German attempts to agitate nationals and foment rebellion.

At the beginning of the war, the Royal Navy maintained three cruisers in South African waters. HMS Pegasus stayed in the vicinity of Zanzibar, while the Admiralty tasked HMS Hyacinth and Astraea to escort regular army troops bound for Europe. The convoy was scheduled to depart August 26. Hyacinth would not return for three to five weeks and Astraea not until September 10. With the cruisers gone, South Africa had only one armed merchant cruiser to escort local forces on the operation against German Southwest Africa. The officer administering the government of South Africa, John H. DeVilliers, and his ministers believed the operation too risky without better naval support, all the more so with the location of Germany’s East Asia squadron unknown. DeVilliers proposed delaying the operation that had been agreed to on August 10 until sufficient naval support became available.

While waiting for adequate naval support, however, South Africa continued to make preparations for the operation, including posturing troops near the land border with German Southwest Africa. Methuen’s prewar assumptions regarding uprisings proved wrong. It was South Africa’s offensive against German Southwest Africa that provoked unrest. During the Second Boer War twelve years earlier, Germany had provided much needed moral support for the Boers against their British foes. Many Boers remained sympathetic toward Germany, and several thousand Boers, including some of the troops in the vicinity of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, objected to expeditions against Germans in the neighboring colony. To avoid participating in South Africa’s campaign against German Southwest Africa, they rebelled against the South African government by declaring themselves free and independent. Because of the revolt, South Africa was forced to recall the expedition against Swakopmund. The situation in German Southwest Africa was so adverse that the cabinet considered diverting the Australia and New Zealand (ANZACS) contingent that was about to start for Aden and send it to the cape instead. To make the trip, the troop transports would require coaling at Colombo, prompting Whitehall to initially order the convoy to proceed there to await developments. Depending on how the campaign unfolded, the cabinet could then decide whether to divert the ANZACS.

South African general Louis Botha, himself a Boer, put down the internal rebellion. With rebels surrendering in large numbers, the situation in South Africa improved to the point that the campaign against German Southwest Africa could resume. While General Jan Smuts advanced from the south at Luderitzbucht, General Botha pressed forward from Swakopmund, beginning on February 7, 1915. Both forces moved inland along the major railroad beds. On May 12, the town of Windhoek, the capital of German Southwest Africa, surrendered to Botha with its wireless station undamaged. The German colonial government had withdrawn to Grootfrontein, in the north. On July 9, 1915, all German forces in German Southwest Africa surrendered.

GERMAN EAST AFRICA

In German East Africa, a small force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck had made repeated raids into British East Africa to cut the Uganda rail line. On each of these occasions, however, the local defense force, the King’s African Rifles, had repulsed the German forces. The crown forces in the British colony of Rhodesia, assisted by Belgians from Katanga, had also repulsed several German incursions into their territories. In Nyasaland, British forces remained in a defensive posture but had managed to disable the German steamer Von Wissmann on Lake Nyasa and gain control of the lake. The British cabinet had already decided to attack German East Africa to help the Royal Navy take control of the seas, but decided subsequently that only the conquest of German East Africa would prevent an invasion of British East Africa. Colonial Secretary Harcourt reported to the cabinet on September 14 that the situation in East Africa had slightly improved. He cautioned, however, that the cabinet should not contemplate aggressive action until reinforcements could be brought forward from India.

The King’s African Rifles were the only full regiment in eastern Africa, so the troops from India provided the needed reinforcements to go on an offensive.51 Consequently, the planning and conduct of the expedition fell to India. The India Office in London directed that the dominion government provide all troops and logistics for the operation and that India also coordinate with the Admiralty, Colonial Office, and the cabinet. The War Office, preoccupied on the European continent, had no interest in German East Africa.

The India Office formed two expeditionary forces to reinforce British interests in East Africa. The India Expeditionary Force (IEF) B, under the command of Major General Arthur E. Aiken, consisted of the 27th (Bangalore) Brigade from the 9th Secunderabad Division, an imperial service infantry brigade, a pioneer battalion, a battery of mountain artillery, and some engineers. Five other battalions (the 29th Punjabi, and a battalion each from Jind, Bharatour, Kaparthala, and Rampur), the 22nd (Derajat) Mountain Battery (a 15-pound artillery battery of volunteers), and a maxim gun battery comprised IEF C, under the command of Brigadier General J. M. Stewart. IEF B formed the main offensive unit for invading German East Africa. The British island territory of Zanzibar, off the coast of German East Africa near Dar es Salaam, became the staging area for the planned operation. IEF C reinforced the King’s African Rifles in defense of British East Africa.

India’s scheme for command and control placed General Stewart and IEF C under the authority of Governor Henry Conway Belfield of British East Africa, who controlled the King’s African Rifles and fell under the authority of the Colonial Office. IEF B also fell under Belfield’s authority when it reached Zanzibar. When IEF B actually entered German territory, however, General Aiken, working for the India Office, controlled the expedition. Similarly, when IEF C entered German East Africa, it also fell under the control of the India Office. This was apparently not so with the King’s African Rifles, which remained under the Colonial Office’s authority. The general plan relied on an overland thrust by the King’s African Rifles and IEF C into German territory along a line from Kilimanjaro to Tanga to threaten Moshi, about halfway along that route. As a sequel, these forces would occupy a line from Tabora to Dar es Salaam. Their purpose was to fix German East African forces in the west so that IEF B could attack Tanga from the sea.

From November 2 through November 5, IEF B assaulted Tanga, and German troops repulsed the attack. Aiken reported that locals in Mombasa knew of his force’s arrival, therefore the Germans probably also knew of the impending attack. IEF B had not achieved any level of surprise at Tanga. Instead of having been drawn westward and fixed by Britain’s overland forces, the Germans had the coastal city defended. Despite this, Aiken believed he could have succeeded at Tanga with the addition of two reliable battalions. He also had difficulty obtaining the support he needed from local naval authorities. No doubt, Aiken’s inability to obtain the cooperation he required was exacerbated by the expedition’s convoluted command relationship. In spite of the aforementioned problems, IEF B nearly succeeded: Aiken lost confidence in his attack and ordered an evacuation at nearly the same time that Lettow-Vorbeck decided that defending the city was untenable.

Contributing to the expedition’s coordination problem, the Admiralty had given guidance to the local naval forces that set their priorities farther to the south. In early August 1914, two Royal Navy cruisers steamed into Dar es Salaam searching for SMS Königsberg. In order to prevent the unnecessary destruction of the city, German East Africa’s governor, Heinrich Schnee, brokered a deal in which he agreed to cease operating the high-frequency wireless station and close the port. So that Tanga, German East Africa’s second largest city and farther to the north, could not support German commerce raiders, the agreement also conferred neutral status on the city. In late October, British naval forces located Königsberg hiding in the Rafiji River delta, south of Dar es Salaam. The Admiralty directed the local squadron to prevent the German raider’s escape and destroy it as soon as possible. With German ports prevented from providing logistics to commerce destroyers, the wireless station shut down, and the primary menace to trade bottled in the Rafiji River, the Admiralty achieved its objectives in the region.

Local naval commanders had also hesitated to support the Tanga operation because of the prior agreement with governor Schnee declaring that port neutral. Moreover, resourcing the Tanga operation would have diverted some of the ships from the Rafiji delta and risked Königsberg’s escape. As long as Schnee held to the agreement, the Admiralty could accept the status quo. The Royal Navy’s interest in subduing the entire German colony waned.

Following the failed Gallipoli campaign confidence in Asquith’s Liberal government faltered. This forced him to form a coalition government in late May 1915 that included several cabinet members from the Conservative party. As a result of reforming the cabinet, Andrew Bonar Law replaced Harcourt as Colonial Secretary. Additionally, Churchill was sacked as First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour replacing him. Bonar Law believed that British prestige and the ability to rule in Africa required the outright defeat of the remaining German forces. General Jan Smuts, previously victorious in German Southwest Africa, took command of the operations in East Africa. Fighting continued throughout the war, and the Allies kept committing troops to the theater without defeating the elusive German commander. Lettow-Vorbeck was the last German to surrender in the Great War. Despite his prolonged resistance, however, the German navy was never again able to threaten British trade in the Indian Ocean.

MESOPOTAMIA

The India Office promised the empire two army divisions and a cavalry brigade for the war. London could exceed that limit and use three Indian divisions, however, for a serious emergency. After the War Office took more troops than those India had offered and replaced them with ill-trained, poorly equipped territorial forces, the viceroy complained to the secretary of state for India. The cabinet had tasked India with protecting the oil fields and pipeline at Abadan, as well as sending forces to invade German East Africa and to defend the Suez Canal. Each of these requirements used one Indian division. The viceroy argued that any reduction in troop levels beyond India’s current level attended too much risk for the army of India to retain imperial territory.

The Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF) D, under the command of Lieutenant General Arthur Barrett, had been sent to Basra, just to the north of Abadan, to establish the defense of the region. The Turks had amassed forces in Baghdad for an offensive to the south that made the Arab sheikhs uneasy and threatened Basra directly. The security of Britain’s position in Mesopotamia hinged on continued Arab support. The 12th Brigade (India) was en route to Basra to reinforce IEF D, but would not arrive until February 7, 1915. IEF D required more forces upriver in the vicinity of Ahwaz to demonstrate commitment to the sheikhs. Barrett believed a battalion at Ahwaz would be sufficient to quiet the Arabs and guard against Turkish raids.

Without Arab support, the division that constituted IEF D would be insufficient to hold Basra. The additional brigade could remedy that problem, but it might arrive too late. Troops at Karna would shift to backfill Basra while another battalion proceeded from the latter to reinforce the Arabs at Ahwaz. The viceroy and the undersecretary of state for India agreed that they should press the War Office to release the Indian divisions from Egypt to reinforce IEF D in Mesopotamia. With two full divisions at Basra, IEF D could advance on Nasiriyah and Amara. Basra, they argued, would remain secure once that offensive drove away the Turks.

The viceroy understood the War Office’s desire to retain an Indian division in Egypt. Nevertheless, in a letter to the War Office dated February 10, he argued that India had a more pressing need in Mesopotamia. If the Turks obtained a victory at Basra, Muslim communities in Persia and Afghanistan would perceive the Turks as strong rulers. As a result, these Muslims would likely side with the Turks, eroding loyalty to the British among the Muslim population and Muslim troops. Not only did the empire risk losing access to Mesopotamia and its oil, but also, without the loyalty of Muslim troops in Persia and Afghanistan, the whole of India faced the risk of a pan-Islamic jihad.

A reply, apparently from the War Office, written in the margins of this correspondence suggested that the India Office instruct the viceroy that troops engaged in other regions were not in a position to rapidly withdraw. Moreover, the note suggested that India had made a mistake when it decided on an offensive campaign in Mesopotamia when it should limit its endeavor to the security of Abadan, an objective that its force was sufficient to guarantee.

Buoyed by previous success and despite the War Office’s admonition, India determined to mount an offensive. Lieutenant General Sir John Nixon assumed overall command in April 1915. He sent Major General Charles Townshend with the 6th Indian Poona Division north along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers to seize Kut al-Amara and Baghdad. Initially Townshend met with success; by October 1915, the army was encamped thirty miles south of Baghdad. Then the Turks counterattacked and repulsed Townshend and his force on November 22 in a five-day battle at Ctesiphon, about twenty-five miles south of Baghdad. Townshend fell back to Kut al-Amara and subsequently became surrounded when the Turkish 6th Army pressed its advantage.

Nixon sent Lieutenant General Fenton J. Aylmer with a force to Townshend’s aid. Aylmer’s attempt to rescue IEF D failed. The setback prompted the War Office to intervene, and it immediately replaced Nixon, who had reportedly also become ill, with General Percy H. Lake. Lake sent Alymer again to attempt to raise the siege of Kut al-Amara, but without success. Lake replaced Alymer with Lieutenant General George Gorringe, who also failed to break the Turks’ stranglehold on Kut. Townshend eventually surrendered on April 29, 1916.

The Mesopotamia campaign embarrassed the British army. Whitehall recalled Lake to stand before the Mesopotamia Commission, established to inquire into the failures of the campaign. Lieutenant General Frederick S. Maude, originally sent to relieve Gorringe, assumed command of Allied forces in Mesopotamia. The War Office wrested control of the campaign from the India Office and then gave Maude newer equipment and reinforcements. For the remainder of the war, British forces advanced steadily northward, which allowed the War Office to erase the stain of Townshend’s surrender.

Nixon’s initial decision to advance toward Kut al-Amara from Basra constituted a serious strategic blunder. The singular reason Whitehall had for sending IEF D to the Shatt al-Arab was to secure the Abadan oil fields. The terrain around Kut al-Amara was no more defensible than that surrounding Basra. Moreover, Kut al-Amara was isolated along difficult and long lines of supply, whereas Basra was easily supplied via the Shatt al-Arab by sea. Had the Turks attempted to dislodge IEF D, the Ottoman forces would have had to overcome the same logistical difficulties to move south as the British did moving north. Moreover, the 6th Indian Poona Division’s defeat at Kut al-Amara did not lead to the Turkish 6th Army advancing on Basra, probably because the Ottomans could not solve the logistical problems involved in conducting a successful campaign southward, from Kut al-Amara to Basra. The British, therefore, controlled the Abadan oil fields throughout the war.

OBSERVATIONS ON THE CAMPAIGN

Each of the overseas expeditions had objectives related to protecting trade. Threats to Britain’s lifeblood came not only from marauders prowling shipping lanes in search of British-owned cargo vessels, but also from the Turkish army possibly seizing the Suez Canal and the Abadan oil fields. Had the Turks closed the Suez Canal, trade between India and Great Britain would have had to travel around Africa. The longer journey would effectively diminish the number of cargoes delivered to the home islands because each ship would require additional weeks to make the journey, meaning fewer round-trips each year. This in turn would contribute to a scarcity of freight capacity, driving up consumer prices. Oil from Abadan was an important British-controlled source of fuel for the Royal Navy. Loss of these oil fields would increase Britain’s vulnerability to fuel price fluctuations and pressure from foreign governments. The expeditions targeted German colonial ports and high-frequency radio transmitters to eliminate logistics and intelligence support for commerce raiders. The objectives for each of these operations show that they were subsidiary efforts supporting an overarching campaign designed to protect British trade.

Securing the integrity of the trade routes where they were vulnerable to direct overland attack, as at the Suez Canal, constituted a higher priority for British and imperial troops than protecting the oil fields at Abadan or conquering German East Africa. The War Office denied requests from the viceroy and the India Office to divert forces from the defense of Suez to Abadan and to increase the commitment to German East Africa. In the Indian Ocean, IEF D proceeded to Abadan with escort while Königsberg remained at large, but this operation’s priority was not sufficient to divert troops from other operations in East Africa or Suez. The oil fields were important, but the fuel it supplied was useless if it could not safely transit the trade routes. Security of the shipping lanes was a prerequisite for the continued utility of the oil fields.

London had originally conceived of the expedition to German East Africa as a means to assist the Royal Navy in its task to secure Indian Ocean trade. Later, the Colonial Office determined that subduing the entire German colony would be expedient for protecting neighboring British territory. The War Office showed no interest in resourcing the expanded goal. Similarly, the Admiralty hesitated to support the Tanga operation when the navy had already achieved its assigned objectives. The Admiralty’s priority was to protect the shipping lanes. The threat to the ocean’s highways came from German raiders (whether warships or merchant vessels converted to auxiliary cruisers), the ports that could serve as logistics bases, and the network of high-frequency wireless stations that helped provide direction and intelligence. Hence, the Admiralty fixed its attention on Dar es Salaam, to the south of Tanga, where robust port facilities and the wireless station were located, and Königsberg trapped in the Rafiji River. The War Office also showed no interest in planning the expedition to German East Africa. Additional forces for the conquest of this important German colony arrived only after Germany’s other African territories had surrendered. Logically, the justification for denying troops to the East Africa expedition was that conquering German territory held a lower priority than extinguishing support to commerce raiders.

The higher priority of sapping the support available to German commerce raiders was evident in the Pacific as well. The Royal Navy and the Australian government avoided occupying German territory that could be effectively neutralized with a straightforward raid. Patey’s decision to halt searching for von Spee’s squadron in order to simultaneously support his convoys, the Samoa expedition, and the Rabaul expedition illustrates the relative priority of these tasks. Searching for the German East Asia squadron ceased so Patey could support the other operations, even though von Spee’s ships constituted Berlin’s greatest naval threat outside of the North Sea and their whereabouts were unknown for a significant period of time. The Admiralty focused on the potentially high payoff of eliminating Germany’s logistics bases rather than futile pursuit of dispersed commerce destroyers. Without logistics, the kaiser’s war on British trade would eventually cease.

Far from racing to seize Germany’s colonies, the forces involved in the overseas expeditions were reluctant to occupy any more of them than necessary to prevent the kaiser’s navy from using overseas ports and wireless transmitters. The manner in which Great Britain executed the sub-campaigns does not support the conclusion that their purpose was to add territory to the British Empire or to hold the kaiser’s colonies as bargaining chips for end-of-war negotiations. The mere act of German colonies surrendering made them available for bargaining chips or expanding the Allies’ imperial holdings, but those outcomes were incidental to the campaign.

The Admiralty strategy relied on severing German commerce raiders’ logistics and intelligence to limit the range and duration of their threat to shipping. Only Royal Navy warships beyond those necessary to support the higher priority overseas expeditions and convoys hunted for German raiders. Individual commerce destroyers that could replenish from their victims, such as Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and Emden, remained at large the longest. As Germany’s overseas ports were overrun, the kaiser’s raiders relied on the extensive Etappen system extant in neutral countries for logistic support. The use of neutral ports placed the German navy’s logistics out of reach of the Royal Navy, and military expeditions were not a suitable solution either. Halting Germany’s remaining naval activity required a significant diplomatic effort.