6 April 1941

What chance would one aircraft, armed with only one torpedo, have of crippling a mighty German warship located in a virtually impenetrable harbour and protected by a thousand guns? Certainly no one would ever have planned such a raid, and any aircraft daring to try and pierce such a defence would have only the remotest chance of survival. But that was exactly the position Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell found himself in at dawn on 6 April 1941. His target, the Gneisenau, was in his sights and he would get no second chance.

The fact that Britain was an island meant it was vital to keep its sea routes across the Atlantic open. Germany’s two large and very capable battle cruisers, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, each displacing 32,000 tons, and quicker and more heavily armed than the Royal Navy’s capital ships in the Atlantic, posed a real threat to the merchant convoys supplying Britain. By early 1941 it was estimated the two battle cruisers had, between them, sunk more than a million tons of Allied shipping, and they were soon to be joined by the Bismarck, the largest warship in the world at the time. If this was allowed to happen, it was clear that the three mighty warships would create havoc in the Atlantic and potentially starve Britain into defeat.

At the end of March the two battle cruisers went into harbour at Brest, on the west coast of France, having just completed their successful Atlantic patrol. This provided a rare opportunity to attack the ships in harbour and so a bombing campaign was ordered by the RAF, to commence immediately, in an attempt to sink the two ships. However, despite a number of bombs dropped against the two ships during a week-long campaign, there was no success. More than a hundred aircraft had attacked on the night of 30/31 March without achieving any hits, and another similar sized force had attacked four nights later, but found it difficult to locate the ships. A further raid the following night had only produced one hit on the dry dock in which the Gneisenau was lying, despite more than fifty bombers being involved in the attack.

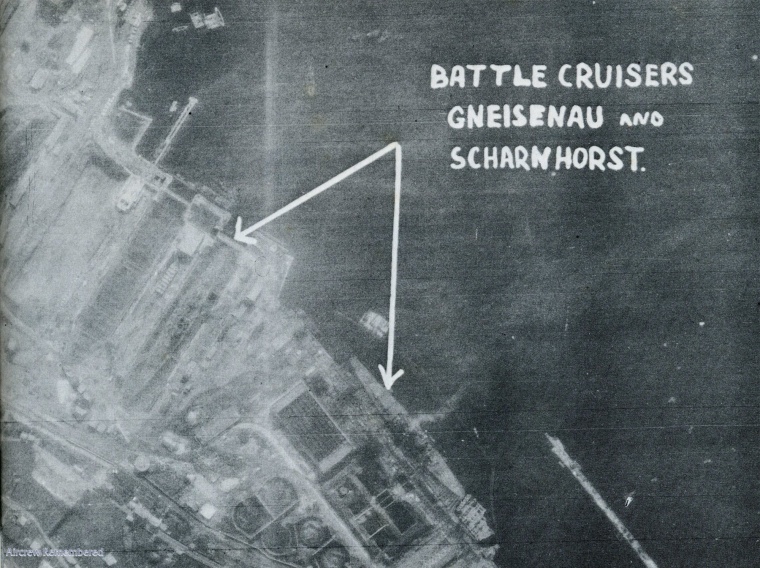

Bomber Command’s attempts to sink the ships had proved costly in terms of resources. More than 250 sorties had been flown during the week and four aircraft had been lost, but only one bomb had landed anywhere near the ships. The RAF now turned to Coastal Command. An aerial reconnaissance sortie revealed the Scharnhorst was moored up alongside the harbour quay and was well protected by torpedo nets, but the Gneisenau had been moved out of the dry dock and into the inner harbour, and was now considered vulnerable to attack from a torpedo-carrying aircraft such as the twin-engine Bristol Beaufort.

An attack was immediately ordered for the following day, 6 April, soon after dawn, with the task falling to 22 Squadron. The squadron was operating a detachment of aircraft from St Eval in Cornwall, having moved to the southwest from its home base at North Coates in Lincolnshire. From St Eval its Beauforts were within striking distance of the Atlantic ports along the Bay of Biscay on the west coast of France, but only six aircraft were available for the raid, with only three of the crews torpedo-trained. The plan, therefore, was to attack in two formations of three, with one formation bombing the torpedo nets while the second wave of three torpedo-carrying aircraft would carry out the main attack against the Gneisenau.

The three pilots chosen to carry out the torpedo attack against the Gneisenau were Flying Officer John Hyde, Sergeant H. Camp and Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell. Born and raised in Scotland, Campbell was still only 23 years old. He was serving with his first operational squadron, having arrived just six months before, and this was to be his twentieth operational sortie. His three crew members were a Canadian observer, Sergeant Jimmy Scott, a wireless operator, Sergeant William Mulliss, and Flight Sergeant Ralph Hillman as air gunner.

The Beaufort crews knew that the harbour at Brest was heavily defended by an estimated one thousand guns of various calibre. Furthermore, the harbour benefitted from the natural protection of hills around it. The reconnaissance photographs had shown the Gneisenau to be moored just 500 yards from a harbour mole, which meant the crews would have to deliver their torpedoes with extreme accuracy. Then, having released their torpedo, the pilot would have to make a steep turn away from the high ground beyond the harbour.

The crews knew from the outset that their chances of achieving any success were incredibly slim, but even so, the raid did not get off to a good start. The aircraft were due to take off soon after 4.30 am but heavy rain at St Eval overnight had turned the airfield into a swamp and had prevented two of the bomb-carrying Beauforts from getting airborne. Even then, the one that did manage to get airborne got lost due to the bad weather, which was not helped by the fact that it was still dark. The three torpedo-carrying aircraft had fared little better. One also got lost in the heavy rain and the other two became separated because of misty conditions over the sea.

The one Beaufort to have pressed on was that flown by Campbell. Unaware of what was happening elsewhere, he arrived at the planned rendezvous point a short distance from the harbour at Brest. It was now starting to get light and, with no sign of the other Beauforts, he decided to circle over the sea some distance from the harbour and watch for visible signs of the bomb explosions from the first wave. But, as it approached 6.00 am, there were still no signs of any such activity in or around the harbour.

Campbell knew that he would soon lose the cover of the murky dawn, as it was getting lighter by the minute. He had to make a decision, and, not knowing what had happened to the others, he decided to press on alone. Undaunted, he started his run-in towards the harbour. With no signs of any other Beauforts around, he knew that his attack would have to be made with absolute precision. There would be no second chance.

The Gneisenau was secured alongside the wall on the north shore of the harbour, protected by the stone mole bending round it from the west. On the rising ground behind the battle cruiser stood a protective battery of antiaircraft guns with other batteries clustered thickly around the two arms of land, encircling the outer harbour. In the outer harbour, and near to the mole, were moored three heavily armed anti-aircraft ships that were guarding the cruisers. Campbell knew that even if he could succeed in penetrating these formidable defences, it would be almost impossible to avoid the high ground beyond the harbour. Yet he still decided to take his chances and to run the gauntlet of defences in order to press home his attack.

As Campbell took the Beaufort down to just above the waves, he was immediately greeted by a wall of flak as the anti-aircraft gunners spotted him running in at low level. As he crossed the mole he passed the three antiaircraft ships below the height of their masts as he hugged the waves as close as he dared. As the only attacking aircraft everything was thrown his way as he ran the gauntlet of concentrated anti-aircraft fire. The final seconds of the run-in would have seemed like an eternity, but he then popped up to 50 feet, just high enough to release his torpedo at minimum range. Finally, with the torpedo gone, he started a steep banking turn away to port and towards the safety of the cloud above.

As it turned out, Campbell’s run-in and torpedo release had been textbook, bordering on perfection, but as he turned away to avoid the high ground and to seek the cover of cloud, his aircraft presented an easy target to the gunners. All the guns in the area caught the Beaufort in a devastating burst of fire and it plummeted into the harbour. The crew stood no chance.

The result of Campbell’s attack was that the Gneisenau was severely damaged below the waterline and the mighty battle cruiser was soon back in dry dock undergoing major repairs to its starboard propeller shaft; she would be out of action for nine months. It was an incredible achievement, given that Campbell had attacked alone and with only one torpedo, to inflict as much damage as he did. He had known that his attack would have to be carried out with precision, and it was.

Such was the bravery of Campbell and his crew, the Germans gave the four airmen a funeral with full military honours. When news of the lone and gallant attack by Campbell and his crew filtered through to London, through the network of the French Resistance, it was announced that Kenneth Campbell was to be posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. The fact that he managed to launch his torpedo with such accuracy, in the face of intense anti-aircraft fire from all around, is testament to the skill and bravery of the young Scot. By pressing home his attack at close quarters in the face of overwhelming enemy fire, and on a course fraught with extreme peril, Kenneth Campbell displayed valour of the highest order.