Wallachian victory at Battle of Călugăreni (1595)

Wallachian Army

After the battle of Mohacs (1526), most of Hungary fell into

Turkish hands, but Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia (today making up

Roumania) were left as semi-independent states in a ‘no-man’s-land’ between

Turks, Poles and Austrians. Wallachia was generally a Turkish satellite, but 20

standards of Wallachians served in the Polish forces, and their princes or

Voivodes sometimes fought the Turks – Michael the Brave winning a notable

victory over them at Călugăreni (1595). Wallachian armies of this period were

entirely of cavalry, mainly nobles, lightly equipped, with spear, shield, sabre

and often bow, occasionally replaced with pistols. A Polish source says they

were very brave, but great looters!

At Călugăreni the Wallachians had the aid of Cossack and

Transylvanian contingents. The Princes of Transylvania fought for and against

most of their neighbours at one time or another and were involved in the early

stages of the 30 Years’ War. Unusually for the area, the Transylvanian nobility

got on fairly well with the peasantry (apart from Count Dracula, I presume) so

that their army included infantry as well as the traditional levy of mobile

cavalry. After 1606, the Princes established landless wanderers – ‘Haiduks’ –

on holdings along the Turkish frontier, on military service terms like the

Austrian ‘Grenzers’.

Opposition to the Ottomans was constant, but the majority of

princes were realists. Aware that their countries were too weak to challenge

Ottoman supremacy directly, they looked for support to Po- land, the Habsburg

empire, and Russia. Theirs was the classic strategy of playing powerful

neighbors off against one another, thereby securing independence. One of the

high points of this delicate game was the reign of Michael the Brave of

Walachia (ruled 1593-1601), who allied himself with the Habsburgs and won

several significant victories over Ottoman armies, notably at Călugăreni in

1595. He also brought Moldavia and the principality of Transylvania under his

rule for a brief time, but his enemies prevailed, and the Ottomans regained

their predominance over the principalities.

Wallachian offensive

Michael led an army of mounted Wallachians south across the

Danube River into Ottoman- held Bulgaria in January 1595. The swift- moving

column systematically captured a string of Ottoman strongholds along the

Danube, including Rusciuc, Silistra, Nicopolis and Chilia. These gains greatly

worried the Ottomans because it threatened their supply line along the Lower

Danube.

In the meantime, Transylvanian Voivode Sigismund Bathory

sought to establish his authority, with Rudolf’s approval, over the voivodes of

Wallachia and Moldavia. Transylvania historically was part of Hungary, but its

ruler often oversaw regional matters on behalf of the Habsburg emperor.

Voivode Aaron of Moldavia dutifully arrived in the

Transylvanian capital of Alba Iulia. Bathory imprisoned and poisoned Aaron so

that he could install one of his own officials, Stefan Razvan, as ruler of

Moldavia. Bathory also summoned Michael, but the Wallachian was busy

campaigning against the Ottomans, so he sent a group of Wallachian boyars

(aristocratic landowners) to act on his behalf. They signed an agreement

whereby Michael became Bathory’s vassal.

Michael expected a large Ottoman army to invade Wallachia to

restore the disrupted supply line to the war zone in northern Hungary. The

Ottomans needed to secure the corridor in order to safely move troops, siege

guns, ammunition and food stores to the battlefront in Hungary. The Ottomans

also wanted to secure Wallachia because they relied on it for grain and horses

for their armies.

Sinan Pasha invaded Wallachia in the summer of 1595 with

115,000 troops for the purpose of securing the Ottoman supply corridor along

the Lower Danube. To oppose him, Michael had 22,000 Wallachian, Székely and

Cossack troops. The native Wallachians and the Cossacks fought mounted, whereas

the Székelys fought on foot.

Michael deployed his troops in a strong position on marshy

ground behind the Neajlov River, south of the village of Călugăreni, to impede

the Ottoman akinji and sipahi horsemen. As they advanced against the

Wallachians on 25 August, the troops of the Ottoman vanguard ran into stiff

resistance while crossing a bridge over the Neajlov.

Once the Ottomans had secured a foothold on the north side

of the Neajlov, the janissaries went to work constructing makeshift causeways

and bridges through the marshes using logs and planks. When his entire army was

on hand, Sinan Pasha attempted a double envelopment with his skilled horsemen.

The Turks never managed to achieve their double envelopment

because Michael moved to seize the initiative. He dispatched a portion of his

cavalry on a wide flanking move in which it assailed the Ottoman flank and

rear. While the cavalry was moving into position, Michael led a spirited attack

on the Ottoman centre, wading into the enemy ranks swinging his double-bladed

axe. The Ottomans fell back in the face of the fearsome counterattack. The

victorious Wallachians seized 15 guns and captured the green banner of the

prophet as a trophy.

Unable to further resist the much larger Ottoman army and

wanting to avoid destruction, Michael withdrew north across the Wallachian

plain to the safety of the primeval woods of the Transylvanian Alps. Sinan

Pasha retook the fortress of Giurgiu and then occupied Targoviste and

Bucharest.

Using captured Ottoman guns to support his men, Michael

defeated the Ottomans at Targoviste in 1595.

Michael requested troops from Bathory, who duly came to his

aid. At the head of a 40,000-strong Wallachian-Transylvanian army Michael

recaptured Targoviste on 18 October. Instead of attacking Michael, Sinan Pasha

retreated towards the Danube for fear that Michael would cut his supply line.

Michael’s troops attacked the Ottomans at Giurgiu on 27 October. The Ottomans,

who were withdrawing to the south bank of the Danube over a bridge of boats,

had to fight a desperate rearguard action to protect their crossing. Sinan

Pasha sacrificed his rearguard in order to get the main body safely across.

Wallachian Cavalryman c. 1575

The original occupants of what is now known as Romania

called themselves Vlachs (not to be confused with a similar word used in Serbia

and Bulgaria for cattle-raisers), and formed three independent states:

Wallachia about 1324, Moldavia in 1359 and Transylvania at the beginning of the

fifteenth century. First they were vassals of Hungary, later battlegrounds for

the interests of Hungary, Poland, Austria and Turkey. At the beginning of the

fifteenth century, the Ottoman Turks appeared on the borders of Wallachia,

which finally fell under their rule in 1526, after the Battle of Mohacs. Prince

Vlad Tepes the Impaler (1418-56) (also known as Count Dracula) gained notoriety

through his cruelty in the struggle against the Turks, and it was from him that

the Turks learned to impale their prisoners on stakes without killing them at

once, a skill they were later to use extensively. After the Turkish occupation,

the Vlachs shared the fate of all occupied peoples. The local feudal lords

(bospodars) often rose against the Turks, and took to the mountains and woods

with their armed bands.

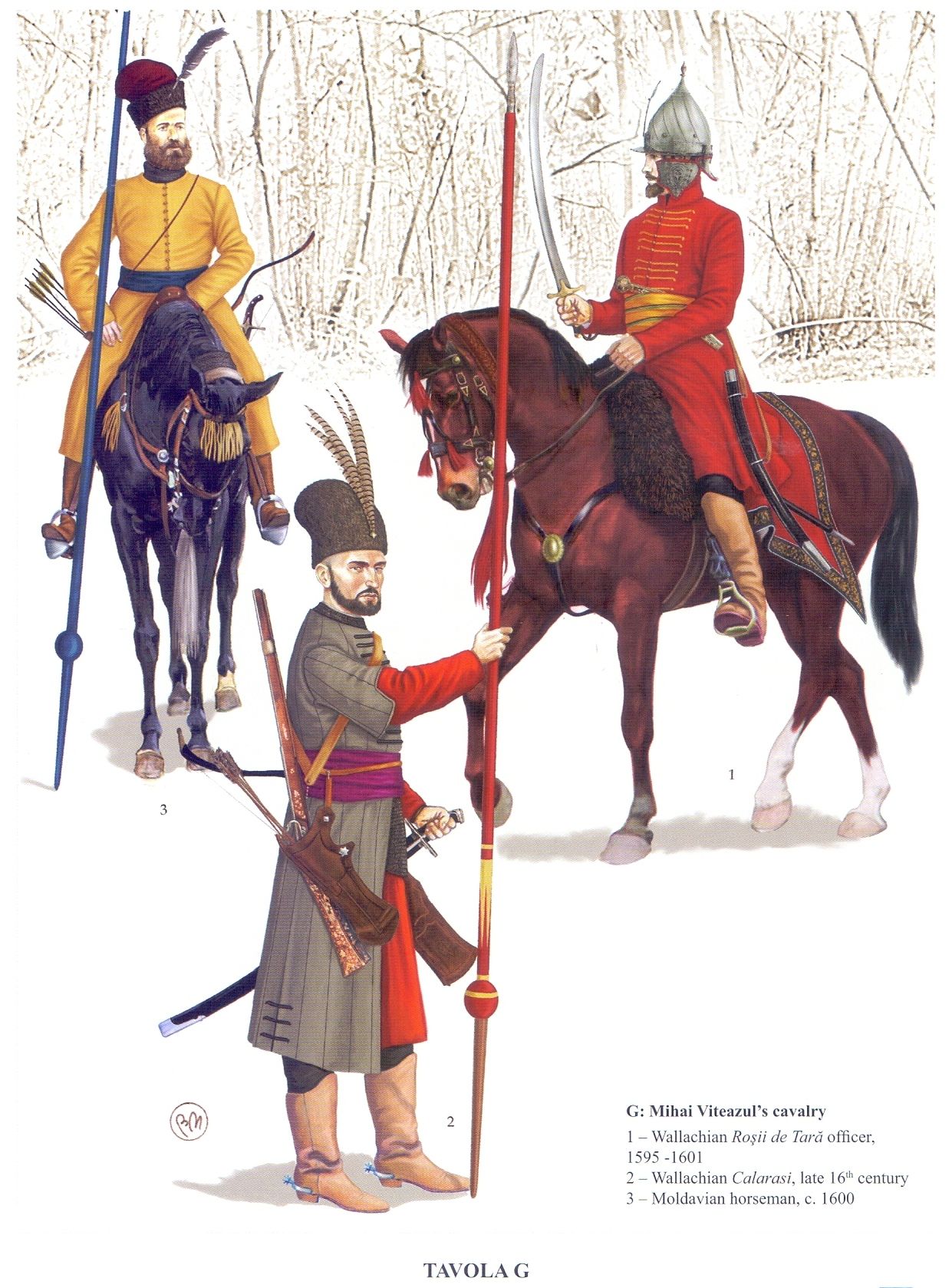

In equipment and appearance, the Vlachs were similar to the

Hungarians and Russians; they wore large fur capes decorated with feathers, and

sported the characteristic long, rounded beards. After their victory over the

Turks at Călugăreni in 1595, Vlach armies became almost completely cavalry

forces. Several contemporary engravings by de Bruyn, made between 1575 and

1581, help us to reconstruct the appearance of the Wallachian cavalrymen.

They belonged, for the most part, to a type of light cavalry

(calarasi), who acquired much of their equipment and equestrian skills from the

Ottomans. Besides training their horses to walk, trot and gallop, the Vlachs

taught them to walk like camels, moving both legs on one side at the same time.

Today one can find horses walking that way, but it is considered a bad trait.

From the end of the sixteenth century, Wallachians served as

mercenary horsemen to both the Ottoman Empire and its enemies – Poland, Hungary

and Russia. They were organized in squadrons (sotnia, from the Russian word for

100) of about one hundred men. At one time there were 20 sotnias in Polish

service in the Ukraine, and one of the frequent motifs on their flags was a

bull’s head. Like the Ottomans, they refused to use firearms for a long time;

their main weapons were spear, sabre and composite bow. For protection, they

wore mail shirts and used a light round shield.