As early as January 1945, the Imperial Japanese Army and

Navy reached agreement (although their cooperation was, as always, limited by

inter-service rivalry) on Ketsu-Go (“Operation Decision”): the final defence of

the Japanese home islands against Allied invasion. A single phrase from the

Precepts Concerning the Decisive Battle issued on 8 April 1945 by Gen Korechika

Anami, Minister of War, will serve to illustrate these measures: all ranks were

exhorted to “possess a deep-seated spirit of ramming”. General Yoshijiro Umezu,

Army Chief of Staff, emphasized that “the certain way to victory… lies in

making everything on Imperial soil contribute to the war effort … combining

the total material and spiritual strength of the nation …” Servicemen and

civilians alike were left in no doubt that the final defence would be to the

death; that all available weapons would be used suicidally.

■ Meeting the Invasion Armada

Imperial General HQ believed (rightly) that an Allied

invasion would be directed first against southern Kyushu and, once a beachhead

was established there, against the Tokyo area, southeast Honshu.

Since the IJN was now almost bereft of surface striking

units, the first line of defence against the invasion armada would be provided

by the remaining aircraft for which pilots and fuel were available – some

10,700 according to USSBS figures – of the Army and Navy. Half of these, 2,700

of the IJN and 2,650 of the IJA, would be kamikaze.

Both the IJN and IJA sought to strengthen the kamikaze units

and to impose some unity of aircraft types within them by producing

purpose-designed suicide planes, of which the IJN’s Yokosuka D4Y4 Model 43 and

Aichi M6A1 are described in Chapter 4. The IJN’s other major attempt at a

“special attack” bomber, intended to be cheaply and quickly manufactured from

non-strategic material, was the wooden-construction Yokosuka D3Y2-K (finally

redesignated D5Y1). The programme was initiated in January 1945 and was aimed

at a production target of 30 per month, but not even a prototype was completed.

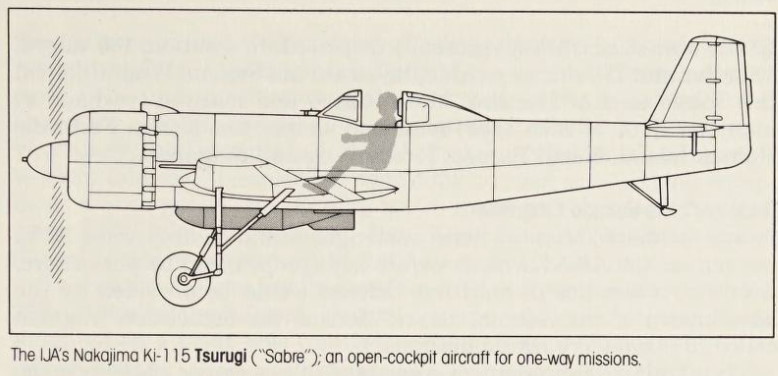

The IJA had more success, in terms of production only, with

its Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi (“Sabre”). This cheap and simply-produced suicide

bomber was built largely of metal, with a wood-and-fabric tail assembly and,

being intended only for one-way missions, with a jettisonable undercarriage.

The open- cockpit aircraft was theoretically suitable to be flown by a pilot

with only basic training, but not surprisingly in view of the speed of the

development programme (design began on 20 January 1945; the prototype flew only

seven weeks later) it proved a beast to handle, especially during takeoff on

its unsprung undercarriage, which had to be modified. Of the 105 examples

completed by the war’s end, none was operational. No examples were completed of

an improved model, the Nakajima Ki-230, or of the Showa Toka (“Wistaria”), a

copy of the Ki-115 for the IJN.

Kamikaze and conventional air strikes, coordinated with

suicidal attacks by the IJN’s 45 remaining fleet submarines, would begin when

the invasion armada was within c.180 miles (290km) of the Kyushu beaches. As

the armada drew nearer, the rate of attack would increase, with troop

transports the primary targets, until, off the beaches, all remaining aircraft

would be committed to a non-stop mass suicide assault which, it was estimated,

could be sustained for up to 10 days. At this time, the kamikaze would be

supplemented by a “banzai charge” by the IJN’s remaining surface units – only 2

cruisers and 23 destroyers remained fully operational in August 1945 – midget

submarines, human torpedoes and explosive motorboats.

Ambitious building programmes for small “special attack”

craft were severely limited by material and power shortages caused by blockade

and strategic bombing. Thus, by August 1945, there were available in the home

islands only 100 koryu five-man submarines; 300 kairyu two-man submarines; 120

shore-based kaiten human-torpedoes; and about 4,000 shinyo and maru-ni EMBs.

With the exception of the comparatively long-ranging koryu, these small suicide

craft were deployed in well-concealed bases in southern and eastern Kyushu and

southern Shikoku. The major locations were: in Kyushu, Kagoshima (20 kairyu,

500 shinyo), Aburatsu (20 kairyu, 34 kaiten, 125 shinyo), Hososhima (ZO kairyu,

12 kaiten, 325 shinyo) and Saeki (20 kairyu); in Shikoku, Sukumo (12 kairyu, 14

kaiten, 50 shinyo) and Sunosaki (12 kairyu, 24 kaiten, 175 shinyo). The IJA’s

EMBs were similarly but separately dispersed. In addition,

180 kairyu, 36 kaiten and 775 shinyo were deployed around Sagami Wan to defend

the Tokyo area of Honshu. More shinyo and maru-ni (perhaps as many as 1,000 of

each type) remained at bases in Korea, Formosa, Hainan Island, North Borneo,

Hong Kong and Singapore.

■ “Fukuryu”: the Suicide Frogmen

It was estimated that the mass onslaught would destroy some

35–50 per cent of the Allied armada before any troops could be put ashore.

Offshore, a last line of maritime defence would be provided by the least-known

of the “special attack” forces: the demolition frogmen called fukuryu

(“crouching dragons”).

Their training had begun at Kawatana in November 1944 (see

here), although the IJN had employed teams of swimmers on hazardous missions

since early in the war; notably at Hong Kong, where skindivers defuzed Allied mines

to prepare a way for landing craft. A Japanese prisoner taken at Peleliu,

Palaus, late in 1944, claimed that he belonged to a 22-strong Kaiyu unit of

swimmers trained to attack landing craft. Each swimmer was armed with three

grenades, a knife and a simple demolition charge: a wooden box of c.160in3

(2620cm3) packed with trinitrophenol (Lyddite) with a fuze cut to the required

length. But the kaiyu units, credited with damaging an LCI in the Palaus and a

DE and an attack transport at Okinawa, were surface swimmers rather than

frogmen.

The fukuryu appear never to have been deployed outside the

home islands. Their role in the final defence would have been suicidal – as

was, to some extent, their training. Their equipment – a loosely-fitting wet

suit; a clumsy helmet not unlike that of a deep-sea diver; bulky air

circulation and purification tanks strapped to chest and back and linked by a

tangle of hoses – was most unsatisfactory. “There were very many [fatal]

accidents during the training of fukuryu”, a Japanese veteran told me, “because

the twin-tank oxygen re-breathing equipment was no good – but nothing better

was available”. Nevertheless, some 1,200 fukuryu graduated from Kawatana and

Yokosuka Mine School by the war’s end, when 2,800 were still in training.

To destroy inshore landing craft, each fukuryu was armed

with a 22lb (10kg) impact-fuzed charge, incorporating a flotation tank, mounted

on a stout pole (much like the anti-tank “lunge mine” described above). If his

equipment functioned perfectly, the frogman could stay at an optimum depth of

50ft (15m) for up to 10 hours, sustained by a container of liquid food.

Construction was begun of underwater pillboxes, concrete with steel doors, in

which fukuryu would shelter from a pre-landing bombardment while awaiting their

opportunity to sally forth and thrust their explosive lances against the

bottoms of landing craft.

The fukuryu would form part of a network of beach defence.

Farthest from the beach were moored mines, electrically detonated from ashore;

then three lines of fukuryu deployed so that each man guarded an area of

c.470sq yds (390sq m); then lines of magnetic mines; and finally beach mines.

Capt K. Shintani, commanding the fukuryu, was somewhat optimistic in hoping

that his men might “cause as much damage as the kamikaze aircraft”.

■ “Special Motorboats”: Amphibious Tanks

Attacks by fukuryu on landing craft might have been

supported by the few completed Toku 4-Shiki Naikatei (“Type 4 Special Motor

boat”; called the katsu) which, in spite of its designation, was an amphibious

AFV. Originally designed by Mitsubishi for the IJN as a troop, weapon or

freight carrier with a capacity of c.10 tons, the katsu was adapted early in

1944 to serve as a coast defence craft. Only 18 examples of this tracked

amphibian were built.

The katsu’s 240bhp diesel engine gave a maximum land speed

of c.15mph (24kmh) or, driving retractable twin propellers, a water speed of

c.4.5kt (5mph, 9kmh). The craft displaced c.20 tons (20.3 tonnes) and was 36ft

(11m) long overall, 10.8ft (3.3m) in beam, and of 7.5ft (2.3m) draught from

track-base to deck-level. It mounted two 13mm MGs in shielded positions forward

and carried two 17.7in (450mm) torpedoes in launching racks to port and

starboard at deck level. The engine was within a pressurized compartment so

that the katsu might be carried on the casing of a submerged submarine; but a

wild scheme – Tatsumaki-Go (“Operation Tornado”) – to transport katsu in this

way to Bougainville, in mid-1944, for an attack on offshore shipping, was

abandoned, as were plans for their deployment at Peleliu and Saipan. They were

held at Kure for possible employment in the final defence. They were slow,

noisy and unhandy.

■ “Operation Olympic”: the Invasion of Kyushu

Operations “Olympic” (later re-named “Majestic”, but rarely

known thus), the invasion of southern Kyushu scheduled to begin on 1 November

1945, and “Coronet”, the Honshu landings planned for 1 March 1946, would have

been the largest amphibious operations of all time. The US 3rd Fleet (covering

force) and 5th Fleet (amphibious force) would employ more than 3,000 warships

and attack transports, excluding inshore landing boats. Anglo-American naval

strength in the Pacific in August 1945 included approximately 30 fleet

carriers, 78 escort carriers, 29 battleships, more than 50 cruisers and 300

destroyers, and close on 3,000 large landing craft.

Landings on Kyushu would be made by LtGen Walter Krueger’s

6th Army, of three Marine divisions, one armoured division and nine infantry

divisions. And although General Marshall, US Army Chief of Staff, feared that

“Downfall” (ie, both “Olympic” and “Coronet”) would cost at least 250,000 US

casualties, a US War Department study of June 1945 predicted that the initial,

critical, 30-day phase of “Olympic” should involve only c.30–35,000 casualties.

The Japanese hoped to destroy up to 50 per cent of the

invasion force before it hit the beaches. And whatever proportion succeeded in

landing would be opposed à outrance at the water’s edge. Imperial General HQ

reasoned that only if the first of the amphibious assaults was bloodily

repulsed might the Allies be brought to moderate their demand for unconditional

surrender. All Japan’s limited resources must be devoted to this “decisive

battle”, with little or nothing in reserve to counter later landings.

Field-Marshal Hajime Sugiyama, overall commander of the final defence, 1st

General Army HQ, Tokyo, decreed in mid- July: “The key to final victory lies in

destroying the enemy at the water’s edge, while his landings are still in

progress”.

In the summer of 1945, Japan had about 6 million men under

arms, of whom some two-thirds were in isolated island garrisons, in Korea, or

with the Kwantung Army in China-Manchuria, where a Soviet offensive might be

expected. Regular Army forces in the home islands totalled c.2,350,000, with

about 3 million Army and Navy auxiliaries (labour battalions and the like). FM

Shunroku Hata’s 2nd General Army, with its HQ at Hiroshima, was responsible for

Ketsu-Go Area No 6, embracing Kyushu, Shikoku and west Honshu; within this

zone, the vital area of southern Kyushu was covered by the 14 infantry

divisions and two armoured brigades (their AFVs near-immobilized by lack of

fuel) of LtGen Isamu Yokoyama’s 16th Area Army.

Every man of military capability had now been drafted, but

many newly-raised units consisted of ill- trained troops without adequate

armament and sometimes even without full personal kit and uniforms. Transport

was severely limited by a shortage of fuel, vehicles, mechanics, and even

draught animals; communications were disrupted nationwide by the B-29 raids;

and the paucity of adequate construction materials meant that beach defence

works remained incomplete.

■ “One Hundred Million Will Die …!”

As early as 1944, Imperial General HQ had begun constructing

a vast underground complex in the mountainous region of Matsushiro, central

Honshu, with a similar refuge for Emperor Hirohito at nearby Nagano. While the

great ones resisted to the last in this Japanese equivalent of Hitler’s

mythical “Alpine Redoubt”, the ordinary civilians must emulate the aspirations

(but not the almost non-existent exploits) of the German “Werewolf” guerrillas.

In November 1944, on pain of imprisonment in default, all

Japanese male civilians between the ages of 14 and 61 and all unmarried females

of 17–41 were ordered to register for national service as required. From this

register, in June 1945, was drawn the Kokumin Giyu Sento-Tai (“National

Volunteer Combat Force”), of ficially some 28 million strong. Cadres from

Tokyo’s Nakano Gakko (“Army Intelligence School”) were sent throughout Japan –

especially to Kyushu – to instruct this militia in the techniques of beach

defence and guerrilla resistance, as laid down in the People’s Handbook of

Resistance Combat.

Sustained by an individual ration of less than 1,300

calories daily – rice being often bulked out with sawdust or replaced by acorn

flour – the unpaid militia, without uniforms but with armbands denoting

combatant status, drilled with ancient rifles (one to every ten men); swords

and bamboo spears; axes, sickles and other agricultural implements, and even

long-bows, “effective at 50yds (45m)” according to the instruction manual.

Empty bottles were collected to make “Molotov cocktails” and “poison grenades”

filled with hydrocyanic acid; local craftsmen manufactured “lunge mines”,

“satchel charges” and wooden, one- shot, black-powder mortars; and small-arms

workshops, their labour forces decimated by dietary deficiency diseases,

produced single-shot, smooth-bore muskets and crude pistols firing steel rods.

Those who lacked arms of any kind were told to cultivate the

martial arts, judo and karate. Women were advised, with the endorsement of

Empress Nagako, to wear mompei (the loosely-fitting pantaloons traditionally

worn only by peasants working their fields), and were instructed on the

efficacy of a kick to the testicles.

Thus, inspired by the spirit of the Special Attack Corps,

the entire population of Japan stood ready to fight to the death. The slogan

was displayed everywhere: “One Hundred Million Will Die for Emperor and

Nation!”

■ The Last Kamikaze Hits

While most of Japan’s aircraft were reserved for use against

an invasion fleet, a few kamikaze sorties continued to be made against Allied

shipping in the Ryukyus. Most were flown by Shiragiku (“White Chrysanthemum”)

units, so called because they were composed largely of venerable training

aircraft; notably a purpose-modified kamikaze version of the IJN’s Kyushu

K11W1/2 Shiragiku. IJA trainers such as the Kokusai Ki-86 (Allied codename

“Cypress”), and Tachikawa Ki-9 (“Spruce”) and Ki-17 (“Cedar”), all three

biplanes, took part in similar operations.

The last Allied warship sunk by a kamikaze aircraft fell

victim to one of these veterans. From USN reports, which describe the attacker

as a twin-float biplane of wood and fabric construction – and thus immune to

proximity-fuzed shells – the aircraft that fell out of the sky over Okinawa at

0041 on 29 July 1945 to strike USS Callaghan was probably a Yokosuka K5Y2

(“Willow”). This flimsy machine, capable of only 132mph (212kmh) with a maximum

bombload of 132lb (60kg), struck a ready-ammunition locker and triggered a

chain of explosions and fires that sank the big destroyer, with 47 dead and 73

wounded, within 90 minutes. In a similar attack on the following night, another

“sticks-and-string” kamikaze badly damaged USS Cassin Young.

It is generally accepted that the last Allied ship struck by

a kamikaze aircraft was USS Borie (DD 704), damaged by the crash-dive of a lone

“Val” while on radar picket duty for TF 38, as the carriers’ aircraft were

launched off Honshu on 9 August. However, Inoguchi and Nakajima (see

Bibliography) state that the attack transport USS La Grange was damaged by a

kamikaze off Okinawa on 13 August. Also, it is possible that the Russian

minesweeper T-152 (215 tons, 218 tonnes) was sunk by a kamikaze during Soviet

landings on the northern Kuriles on 18–19 August, when a few suicide sorties

are believed to have been flown by IJA aircraft from Shimushu Island.

■ “Body-Crashing”: the Ramming Interceptors

On 14 June 1944, Boeing B-29 Superfortresses struck for the

first time at the Japanese home islands. Most early raids were made at high

level (above c.30,000ft, 9150m), but although Japan’s air defence was deficient

in both AA guns and aircraft with the speed and combat ceiling successfully to

intercept the Superfortresses – of 414 B-29s lost, only 147 fell to Japanese

interceptors or AA fire – it was felt that the results of such operations did

not justify even the lowest loss rate.

Early in 1945, MajGen Curtis LeMay took over the

Marianas-based 21st Bomber Command from BrigGen Haywood Hansell, adopting a

policy of low-level incendiary raids at c.5–6,000ft (1500–1800m) by B-29s

virtually unarmed for extra speed. By August, LeMay could claim that fire raids

had completely shattered some 58 major cities and that by bombing alone Japan

would soon be “beaten back into the dark ages”. Fire raids indeed caused far

greater material and moral damage than the two atomic bombs: on 9–10 March, in

a raid by 325 B-29s, 15.8 sq miles (41 sq km) of Tokyo were gutted and c.84,000

killed and more than 100,000 injured (compared to c.78,000 dead and 68,000

injured in the atomic blast at Hiroshima). In a fire raid on Toyama on 1–2

August, no less than 99.5 per cent of the city was devastated. And when Prince

Konoye told the USSBS that the major factor in Japan’s decision to surrender

was “fundamentally … the prolonged bombing by the B-29s”, he was speaking of

the fire raids. One Japanese statesman, however, referred to the atomic

destruction as “the big kamikaze that saved Japan”; meaning that the terrible

civilian casualties sustained in just these two strikes afforded a decisive

argument to the peace faction.

With fuel stocks low, factories and repair facilities

dislocated, and many aircraft lacking trained pilots or held in reserve for the

final kamikaze onslaught, the Japanese air arms proved unable to deal

effectively with the low-level raiders and thus increasingly resorted to

suicidal aerial ramming interceptions. Isolated instances had occurred earlier

in the war. On 4 July 1942, Lt Mitsuo Suitsu, enraged when his naval air

squadron’s field at Lae, New Guinea, was badly damaged by US bombers, fulfilled

a vow of vengeance by destroying a Martin B-26 Marauder in a head-on collision

with his Zero. The first Army pilot credited with such self-sacrifice was Sgt

Oda who, also flying from New Guinea and unable to maintain the altitude

conventionally to engage a B-17 that was “snooping” a Japanese supply convoy,

brought down the Fortress by ramming with his Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar”.

Tai-atari (“body-crashing”) tactics were not invariably

fatal: a few US bombers were destroyed by Soviet-style Taran attacks, their

tail assemblies chewed away by fighters with armoured propellers. USAAF

personnel reported the first cases of what they judged to be deliberate ramming

during a raid on the steel works at Yawata, Kyushu, on 20 August 1944. Of four

bombers lost over the target area, one fell to AA, one to aerial gunfire, and

two to a single Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (Dragon Killer; “Nick”): the “Nick” rammed

one B-29 and the debris of the two aircraft brought down another.

In February 1945, an IJA manual stated that against B-29s

(and the expected B-32 Dominators, of which only a handful became operational)

“we can demand nothing better than crash tactics, ensuring the destruction of

an enemy aircraft at one fell swoop … striking terror into his heart and

rendering his powerfully armed planes valueless by the sacrifice of one of our

fighters”. The manual noted that only partly trained pilots need be used and

recommended as rammers the Nakajima Ki-44 Shoki (Demon; “Tojo”) and Kawasaki

Ki-61 Hien (Swallow; “Tony”), on the dubious grounds that their designs gave

the pilot a faint chance of baling out immediately before impact.

Earlier than this, in November 1944, the 2nd Air Army’s 47th

Sentai formed the volunteer Shinten Sekutai squadron, dedicated to ramming

attacks in “Tojos”. Their successes included the destruction of a B-29 over

Sasebo on 21 November by Lt Mikihiko Sakamoto; another B-29 on 24 November (one

of only two Superfortresses brought down in a 111-strong raid); and two B-29s

(out of only six lost from a 172-strong force over Tokyo) on 25 February 1945.

Fighters of the Kwantung Army also adopted ramming tactics, bringing down two

B-29s over the Mukden aircraft works on 7 December 1944 and another on 21

December. On both occasions, Japanese aircraft also attempted air-to-air

bombing, releasing time-fuzed phosphorus bombs above the US formations. At

least one B-29 was destroyed by this method, which was also used in the defence

of the homeland.

A less extreme measure than ramming was the formation at

Matsuyama NAFB, Shikoku, in January 1945 of a fighter wing led by Capt Minoru

Genda and including Saburo Sakai and other “aces”. Flying the Kawanishi N1K2-J

Shiden (Violet Lightning: “George”) – probably Japan’s best interceptor; only

c.350 were built – they achieved especially good results against Allied carrier

strikes. On 16 February, WO Kinsuke Muto was credited with engaging

single-handed 12 F6F Hellcats from USS Bennington over Atsugi, Tokyo, shooting

down four and driving off the rest.

■ Attempted Aid from Germany

Unable to produce in sufficient quantity such advanced

interceptors as the Kawasaki Ki-100 (396 of all models built), the Kawasaki

Ki-102 (“Randy”; 238 built) and the Mitsubishi A7M3-J Reppu (Hurricane; “Sam”;

prototype only), or to bring to operational status the Funryu (“Raging Dragon”)

surface-to-air guided missiles, Japan sought German aid. Plans, and in some

cases completed models, were acquired of the Bachem Natter, the Reichenberg

piloted-bomb (built as the Baika), and the Messerschmitt Me 262 twin-engined

jet fighter-bomber. A prototype based on the latter, the IJN’s Nakajima Kikka

(“Orange Blossom”), flew on 7 August 1945; if production had been attained it

was to have been deployed in concealed revetements as a “special attack”

bomber.

A major effort at a point-defence interceptor was the joint

IJN/IJA project for the Mitsubishi J8M1 (Navy) or Ki-200/202 (Army) Shusui

(“Swinging Sword”), a near-identical version of the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt

Me 163 Komet. Rights to produce a version of the Komet’s airframe and Walter

HWK 509A bi-propellant (T-Stoff and C-Stoff, which the Japanese called Ko and

Otsu liquids respectively) rocket engine, with a completed example of the

aircraft itself, were purchased as early as March 1944; but only one Walter

unit and an incomplete set of blueprints reached Japan. Germany’s final effort

to provide her ally with more material on the Komet and other “special weapons”

was made on 2 May 1945, when U.234 (Cdr Johann Fehler) sailed from Norway for

Japan with high-ranking Luftwaffe officers, technicians, and two Japanese

scientists aboard. En route, Fehler received the news of Germany’s collapse

and, as he headed for the USA to surrender his boat, both Japanese committed

seppuku.

In Japan, training with the Komet-replica MXY8 Akigusa

(“Autumn Grass”) glider began in December 1944. The first powered flight was

attempted on 7 July 1945 at Yokoku airfield, Yokosuka. Successfully jettisoning

the takeoff trolley, LtCdr Toyohiko Inuzuka had reached c.1,300ft (400m) when,

probably because of a fuel line blockage caused by the steep climb, the engine

flamed out and the Shusui stalled and crashed, mortally injuring Inuzuka. Later

that month, an explosion of the volatile fuel mixture during ground testing

killed another of the project’s officers. Many similar fatalities – especially

during the hard skid-landings that often brought the liquid propellants

violently together – had occurred in Germany, where the “Devil’s Egg” was

regarded by many Luftwaffe personnel as semi-suicidal at best.

The Japanese rocket interceptor differed little from its German pattern. The J8M1 had a span of 31.2ft (9.5m), a length of 19.86ft (6.05m) and a height on its jettisonable trolley of 8.86ft (2.7m). Powered by a Toko Ro.2 motor giving 3,307lb (1500kg) thrust for up to c.5.3 minutes, it was estimated to be capable of a maximum 559mph (900kmh) at 32,810ft (10,000m); thus probably having a range at optimum flight profile of less than 60 miles (96km). Its armament was to be two wing-mounted 30mm cannon – although if the planned production of more than 1,000 examples by August 1945 had been achieved, it is likely that many would have been expended in ramming attacks after exhausting their ammunition of 50 rounds per gun. In the event, only seven Shusui, which were to have been operated by the 312th Naval Air Group, were completed by the war’s end.